THE POLITICAL GUILLOTINE

I can understand why my father didn’t like the politics of

large corporations such as P&G. Plenty of politics took place in his own

company, but he didn’t have to worry about it. He owned the company. I did have

to worry about it, however, at J. Walter Thompson, although there was probably

less political maneuvering there than in the hierarchy of our large client

corporations.

But, inevitably I ran afoul of politics, and almost lost my

job.

On behalf of our client, the Institute of Life Insurance,

our group pioneered the effort to sell insurance not only to male heads of

household but also to married and single women. We had just finished a couple

of highly creative commercials (of which one later won a first prize in its

category in the International Advertising Film Festival in Venice), and I

received a call from the production company that the first prints were done and

ready to be picked up. I came back into the Graybar Building with the reels

under my arm and walked into a crowded elevator to get to the seventh floor to

deliver them to my management supervisor. That’s when I heard, from the back of

the elevator, the distinctive voice of Chairman Strouse say, “Hi, Roy, those

wouldn’t happen to be the prints of our Institute commercials, would they?” A

hot-flash went through me when I told him they were, immediately alarmed that

the next thing he might say was to get them to the screening room so we could

look at them. That’s exactly what he said.

As soon as I got back to my office, I contacted my account

supervisor and told him what happened. He warned we had better get in touch

with our management supervisor before we set up the screening. It was then

about 2:30 pM and our top boss was nowhere to be found. He had a long business

lunch with a client and couldn’t be reached. All of us were used to taking

fairly long lunches when clients were involved, but knowing the client he was

lunching with, I thought this one might be longer than usual.

About 2:45 pM I received a call from the chairman’s office

wanting to know which screening room had been set up. I stalled a little longer

and then at 3 pM I received a second call from his of

fice. Not daring to wait any longer, I booked a screening

room and paced the hall until the third call came at 3:15. In the meantime my

management supervisors’ secretary sent scouts to our frequented restaurants in

New York City looking for him, without success. I stalled as long as I dared,

and when 3:30 came, the chairman joined us to screen the commercials without

our leader.

That’s what you really call being caught between a rock and

a hard place. To put it mildly, I caught hell when my boss returned at 4:30

that afternoon. The next day I found myself off the account. I thought about

going to Mr. Strouse to let him know the result of the position I had been put

in, but that could have had some far-reaching repercussions, so I didn’t.

Within a few days, I was moved to the fourteenth floor of

the Graybar Building into a massive wood-paneled, high-ceilinged corner office

with two windows and its own private bathroom. Anyone entering the office would

have thought I was running the company. But I was waiting for the axe to fall.

The fourteenth floor, if you weren’t in media buying, was the floor to which

you were temporarily exiled when you were unassigned, retired early, or fired.

The benevolent nature of the J. Walter Thompson Company gave everyone in that

position an office to work out of and plenty of time to locate another job

before being removed from the payroll.

In 1967 I was still on the Review Board, but all of the

other jobs I created had been reassigned. I had been removed from a key

account, and I felt the way I did when I busted out of Cornell. I contacted

friends I had in head-hunting businesses in the City to help me start looking

for another job, and I had a number of successful interviews in New York during

the next few weeks. Among them was Grey Advertising and BBD&O, which was

also located over Grand Central Station. But decisions to hire at my level

depended on openings, so there was no quick promise of a job.

To my surprise, my exile turned out not to be the end of the

line. It didn’t take long for a memo to go out from Philip Mygatt, the

personnel director of JWT’s creative department. “All of you know Roy Park

through assignments…with the Review Boards and Research Groups. I have asked

Roy Park to join me in various aspects of the administration of the department.

I know you find he will carry out his duties with his customary effectiveness

and good spirit,” it read.

Among other things, working together we developed an

information-sharing program similar to the one I put in place for account

management through an initiative we called the Creative Forum Papers.

I was also asked to coordinate the JWT Luncheon Speakers

Program and was able to attract speakers such as author Walter Lord; William

Emerson, editor of Saturday Evening Post; Art Buchwald; researcher and public

opinion pollster Elmo Roper; Harper’s magazine editor-in-chief John Fischer;

John Scott, editor-in-chief of Time, Inc.; Chancellor Dean E. McHenry,

University of California, Santa Cruz; and Albert Parry, chairman of the

Department of Russian Studies at Colgate University.

In 1968, this experience led to my assignment as a personnel

group head, working directly with Bob Hawes, head of the JWT personnel

department. In his memo to senior management, he said, “About a month ago, we

tapped Roy Park for this assignment because he has certain characteristics one

finds in good intelligence men, and we discovered he could handle this

assignment in addition to his other duties.” I was put in charge of a

sophisticated new national program directed at recruiting senior management and

top creative people, and was able, in that capacity, to bring in some high

profile talent.

During this time, I also did some writing on the side. An

article I wrote entitled, where does ALL the Best MeAt go?, published in the

American Way magazine in 1968 led to an offer of a public relations position

from the meat packing industry. Of course I turned it down. Now, if that offer

had crossed my path in 1967, I might have taken it.

In 1969, J. Walter Thompson was about to go public, and in

every press release the company put out, the RCA account was always mentioned.

Thompson was the company handling accounts such as “Kodak, RCA and Ford,” or

“Lever Bros., Standard Brands and RCA,” or “RCA, Liggett & Myers and Pan

Am.” In all cases, RCA was one of the top clients mentioned, and for one reason

or another, at this sensitive time, the company was in trouble with the

account. The last thing it needed was to lose RCA just before its public

offering, so every effort was made to save it.

To do this, they started at the top, bringing back Jack

Morrissey, a top manager from another agency who had worked with RCA in the

past, and whom RCA respected as brilliant. They then began recruiting top

people from within the agency to bring together an entirely new creative and

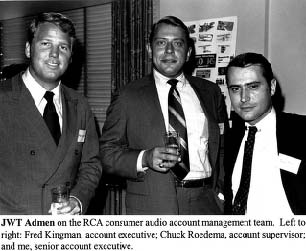

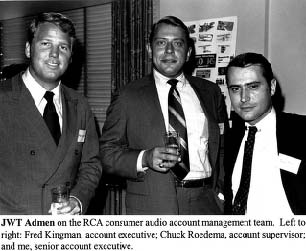

marketing team to handle the account. Luckily, I made the list and was chosen

as senior account executive on RCA’s consumer audio products and blackand-white

television lines. Our group also was to handle all of RCA’s trade, premium and

military service campaigns as well as its international advertising.

My teammates were dynamic, energetic and creative—and

sometimes off-the-wall. Our job was to come up with a whole new image for RCA’s

consumer products. We not only came up with a new image, we actually came up

with ideas for new products that ultimately were manufactured and successfully

sold, particularly to young adults.

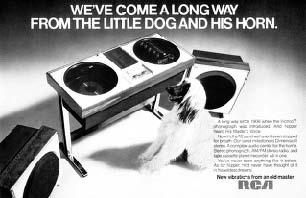

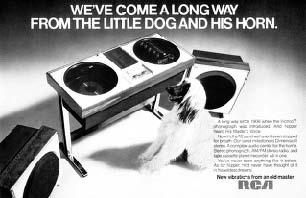

Under the theme “New vibrations from an old master,” our

advertising in magazines including Life, Look, Time, Esquire, Sports

Illustrated, Playboy, Saturday Review, House Beautiful, and House and Garden

announced “We’ve come a long way from the little dog and his horn.” The

cassette tape line was featured with headlines such as FroM stevie’s First

BirthdAy to Beethoven’s ninth, wall clock radios were “Stick ’em up,”

one-and-a-half-inch-wide radios from the Indianapolis Company were “Indiana

Slims.” Products from the military market were “Our new recruits,” and we

bragged for the RCA sound systems: “These speakers can blow out a match.”

It felt great to help breathe new life into one of the

oldest companies in America, and the account was saved. J. Walter Thompson’s

public offering came off without a hitch.

Shortly after we got going on the RCA account, the company

was the first advertising agency to be hit with the government’s Affirmative

Action program. The agency was a test case and we knew we were on the line. We

had plenty of women in high positions in the agency at that time, so the

emphasis was on recruiting minorities. One of the young people recruited was

assigned to me as an account executive on RCA. His credentials were impeccable.

He had graduated from an Ivy League college with an MBA. He was hired at more

than I was making at the time. But once he got the job, he became quite

laid-back, and his cavalier attitude gave me fits. One instance of his

fecklessness came when our full team flew to Las Vegas in preparation for a

week of presentations to key RCA personnel. Thousands of national and

international RCA sales and management people from all over the world were

being flown in for the event, which was the first screening of the consumer

campaign for all RCA products for the coming year. We left our apprentice

account executive behind in New York to fly out with the final creative

material while we traveled in advance of the meeting to set things up. He was

scheduled to come in with the material the day before the sessions were to

begin, and two of us met him at the airport. He came off the plane whistling, and

we went with him to the baggage-claim area to pick up the presentation

material. A single bag came around the conveyor belt, which he picked up,

saying he was all set to go. We looked around and asked him where the creative

material was for the presentation. There was a moment of silence. He had

forgotten to bring it with him. Needless to say, we booked him on a turnaround

flight to New York to get it back on the red-eye that same night. Bottom line,

the next day, the presentation went fine. I had an interesting time in Vegas,

didn’t lose any money at the tables and recovered nicely when I arrived back in

New York.

Jerry Della Femina said, “Advertising is the most fun you

can have with your clothes on,” and I’m inclined to agree. Another way of

putting it, to keep it in the “G-rated” category, was the advice of Foote, Cone

& Belding’s Fairfax Cone. “Advertising,” he maintained, “is what you do

when you can’t go to see somebody. That’s all it is.” And I like David Ogilvy’s

advice to copywriters; “The consumer is no moron. She’s your wife.”

All in all, I loved every year, every day, and every minute

working for J. Walter Thompson. In 1970 its worldwide billing was $774 million,

with its closest competitors being McCann Erickson with $543.9 million,

Y&R: $503.5 million, Ted Bates: $424.8 million, and Leo Burnett with $422.7

million.

My experience at JWT was more than I had hoped for. It

combined all of the things I had been taught at two great universities. It gave

me a great opportunity to practice my inclination for political peacemaking,

taught me how to work as part of a team, improved my writing style, creative

thinking, presentation and sales approach, and sharply honed my ability to

survive.

But the time had come to be thinking along new paths. My

family was growing and the commuting ate into the little time that I had to

spend with them. The decision was forced sooner than I had planned. A

devastating family health crisis required my family’s immediate return to the

South. I’ll come to this later, but in 1970 when I notified J. Walter Thompson

I would be leaving, I received a letter from RCA’s vice president of

advertising services, John Anderson, saying: Jack Morrissey tells me that you

decided to drop out of the New York rat race. I doubt you will ever regret it.

This is just to say that your efforts will be deeply missed on the RCA account.

In the rush of everyday business, particularly in the last chaotic year, we may

have given you the impression that your conscientiousness has gone unnoticed.

Believe me, that was never the case.

Our very best wishes for your continued success in your new

position, and thanks again for your many contributions to our advertising in

recent months.

And so I left the “if I can make it there, I’ll make it

anywhere” city feeling pretty good. During my time at J. Walter Thompson, my

father had brought his broadcast holdings up to fourteen stations with John

Babcock’s help, whose path had led him back to my father in 1964, as he relates

in the next chapter.

(Back to Contents)