CHAPTER 15: THE “ITHACA TRAP”

As his son living in Ithaca, a lot of people have asked me

over the years why my father continued to headquarter in this small town. While

I was mobile and moving around, I wondered, too. I know why he originally moved

to Ithaca, and how he went through his earlier careers there. But when he

started building a media empire, access to financial institutions and ease of

travel for prospects, employees and others with whom his business was involved

would have been better situated in a place like New York City.

After he concluded the sale of the Duncan Hines Institute to

Procter & Gamble, my father could afford better housing. Once his business

was sold, he was free to go anywhere, and I suspect my mother may have been

having some thoughts about returning to the South. At the time, both my sister

and I were away at school so the extra room wasn’t needed, but the purchase of

a larger home was an incentive for my mother to stay in Ithaca where my father

already had investments in real estate.

As was his style, Pops had already started exploring the

possible purchase of an estate in the Ithaca area, regardless of the fact that

none were for sale at the time. He had approached people and families that

owned the kind of property he was looking for, and, in particular, became

friends with one older gentleman which assured, when the gentleman died in the

mid-1950s, that a first right of refusal had been made part of his will.

The house, situated on seven acres in the Village of Cayuga

Heights, was a stone mansion built by stonemasons brought over from Italy, many

of whom remained in Ithaca after the project was completed. I am sure it wasn’t

the weather that kept my father here, since he wouldn’t know a snow shovel from

a walking cane, but with the nature of this commitment, it was difficult for my

mother to push for a move elsewhere. At any rate, to keep her happy, Pops gave

my mother carte blanche with interior decorators and furnishings. Not only was

the house splendidly fitted out, it also served as a refuge and fortification

in which my father could retreat from what in many ways for him was a hostile

world out there.

As you know from my childhood, my mother loved animals, and

my father’s estate provided ample room for dogs and peacocks. The original

peacocks were loud, but eventually, to keep peace in the neighborhood, another

species of peacock was found with a quieter call.

But despite this settling in, it is interesting that over

the years my parents did little shopping in Ithaca, preferring New York City

for purchases and medical care. But the Ithaca trap had firmly snapped shut on

my mother, and to an extent on my sister and me. It also afforded an excellent

snare for my father’s headquarter employees.

I learned over the years Ithaca was the ideal environment

from which my father could run his company. First, its location is “centrally

isolated,” which gives Cornell University fits when it comes to attracting

recruiters, even from New York City, for its graduating students. Rail service

ended forty years ago. The airline schedules are abysmal, and getting worse. No

recruiter can get in to conduct a meaningful interview schedule and back out in

a day. And no disgruntled Park employee could go across the street to find a

new job, with no other jobs in their specialized categories of expertise

available in Ithaca, NY.

Other escape routes were also sealed. My father told me he

did not believe in sending his executives to association meetings or business

conventions, feeling it too easy to have employees recruited away at these

affairs. He belonged to all the right associations, but if anyone from

headquarters attended the meetings, it was usually my father and Johnnie

Babcock.

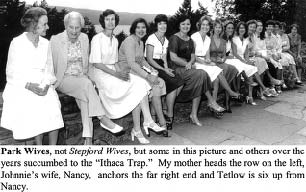

The other part of the trap was that Ithaca offered readily

available housing in a country setting, ideal for enticing people from

higher-cost-of-living areas around big cities. My father made a point of meeting

the wives of prospective employees, hiring those with the most aggressive

wives. He knew when a wife was ensconced in an expensive house, and had a

liking for expensive trappings and a high style of living, they would encourage

their husbands to make more money. And they would tolerate the extensive travel

necessary to their husbands’ job.

The only exception to this rule was me. When I moved to

Ithaca, Pops insisted I rent a house for a year, even though by that time I had

enough money to buy one from the proceeds of my first house. Before I made a

commitment, he made sure it was my toe that was put in the water, not his. At

that time, Ithaca did not offer many houses to rent, but with a dog and two

kids we could not have existed again in a condo or an apartment. The only house

for rent I was able to find was so small that we used the dining room for a

third bedroom and ate in the kitchen. Shades of my sister and me growing up.

The yard was so small that our dog didn’t like it either. The Malamute ran away

every chance he got.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Ithaca was not yet a gleam

in my eye. While the Upstate New York atmosphere was working for my father, the

bright Big Apple lights I commuted to from cramped quarters in Westchester

County were beginning to dim.