QUIRKS AND CHARACTERISTICS

There was another side of my father, not often shown, but he

could be sentimental and at times prone to whims. These inconsistencies could

confuse people making it difficult for them to categorize the man.

When he was decorating his office at Terrace Hill, which

overlooked the city, for example, he moved part of a wall back about three feet

“at considerable expense and effort” because he didn’t like square rooms. He

brought the black marble fireplace from the old mansion at 408 East State, site

of his former offices, to Terrace Hill and installed it prominently. But he did

not hook it up to a chimney. He also brought a chandelier from an old mansion,

as well as some massive paneled doors. The huge office was furnished with

leather and fruitwood French provincial furniture to make it look like an

elegant living room. My father felt that if you spent so much time in a place

you needed an atmosphere conducive to doing your best work.

His office was described by reporter Floyd Rogers of the

Winston-Salem Journal in May 1988 as “a roomy, walnut-paneled office on the

fifth floor of his gracefully aging office building on Terrace Hill here. But

it is not a lavish office.” In truth, having a comfortable office was

practical—God knows he spent enough time there. In any case, what most people

simply don’t understand is that my father, and people like him, work for the

sheer joy of it and probably would pay money to work if that was the only way

they could do it. My father said in the Charlotte Observer, “You must remember,

a person’s worth is not the amount of his assets. It’s the amount of his assets

minus his liabilities.”

In minimizing his liabilities, where most people avoid it,

my father welcomed turnover. He felt it kept payroll costs down. I feel exactly

the opposite. The cost of the search and recruiting, interviewing, training and

payroll setup, on top of moving costs and the long-term costs of losing trust

and loyalty, make turnover an anathema to me. Dave Feldman and I have worked

together for thirty-five years through thick and thin. My managers average

twenty years with the company. We even brought some back after they left for a

period of time for other jobs.

My father was frugal, but he wasn’t cheap. Except for the

limited salaries he paid employees, he was generous with friends and colleagues

and to those whose companies he had targeted for purchase.

But anyone you know who went through the Great Depression

was changed. You never forget what it was like. If you started without money,

there was no way to get it, and if you started with it, you could end up with

nothing. Few had money, and it affected everyone who went through it for the

rest of their lives. After all, Pops started with nothing. Add his experience

during the Depression to that. So he was frugal with me, and this really

applied while I was in college. I was chained to a strict budget for essentials

of rent, food, laundry, clothing, textbooks, etc. and it kept me from being

spoiled.

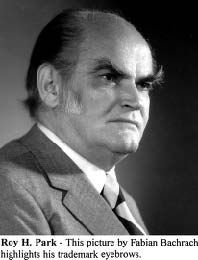

My father also had another distinguishing feature: bushy

eyebrows, very bushy. Woe to the barber with any gardening experience who

sought to take a brush cutter to those bushes. In fact, his eyebrows, like

misplaced mustaches, were so unique that a feature writer for the Ithaca

Journal, Franklin Crawford, in his “Frankly Speaking” column, wrote in 1991:

“One of the punishments for mocking or making funny names about the City of

Ithaca’s new Chevy Caprice cars, if made among two or more persons and one of

those persons is wearing Birkenstock sandals, $1,000, 30 days in jail, or 250

hours of community service including the grooming and maintenance of Roy Park’s

eyebrows.”

A reporter for the Ithaca Journal, Judith Horstman, in a

1972 article headlined, ithACA’s roy pArk: A MAn oF MAny CAreers, described him

as a dapper dresser, with a soft-spoken and gentlemanly manner; she said he was

“a person who retains a southern charm and reminds you he was born and educated

in North Carolina.”

She said that on the day of the interview: Park was wearing

a subdued plaid suit and I noticed two watches. “Duncan Hines rather liked

watches,” Park explained. “So I used to search out all the unique watches I

could, and give them to him. In the process I got a little hung-up on it

myself, and now I must have, oh, I expect 40 watches now.”

He also has an antique Packard and Duesenberg that are in

prize-winning condition. “I don’t drive them much,” Park said wistfully. “It’s

a lot more fun before you get them in show condition. Then you start worrying

about a pebble flying up or something, and damaging the finish.”

In contrast to these possessions are some others he appears

to value almost as much and which he keeps in his office: copies of the

guidebooks he wrote for Duncan Hines; empty cake mix boxes with the Duncan

Hines label; and some cast-iron toys his wife’s father made in his

manufacturing business at the turn of the century.11 Keeping all of these

things in mind, I wasn’t too surprised to hear an anecdote that probably sums

up Pops’s personality. A Cornell student who spent some time interviewing my

father and watching him work was awed and exasperated by his methodical,

organized approach to everything. As he finished his interviews, the student

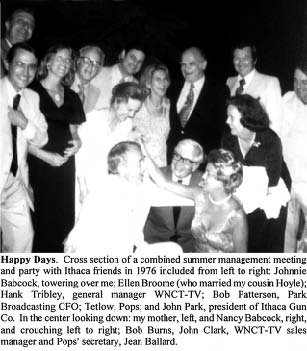

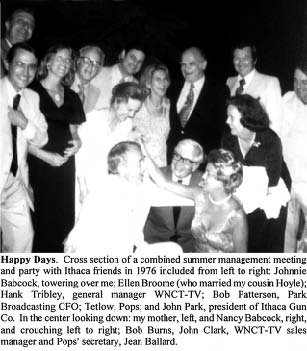

somewhat sarcastically asked Park’s administrative secretary, Jean Ballard,

“Mr. Park certainly does everything in an organized manner. I’m curious, did he

meet his wife that way?” “I really don’t know, so the next day I asked Mr.

Park,” said Mrs. Ballard, “and he burst into laughter.” “Good grief, no,” he

said. “I met her on a blind date.” In his interview with Dumbell in the

Charlotte Observer, my father was described in this way: On the terrace

outside, a gale wind swirled the remains of a 10-inch snow that had fallen the

day before. The wind’s howl could be heard inside over the indignant squawk of

a small caged parrot. Park released the bird, smiled as he stroked its colored

plumage, then replaced it in the cage, and now the bird was affronted. [What

Dumbell didn’t know was that my father usually shared his Rice Krispies with

the bird.] [The interview continued] Park wore a brownish, chalk-striped suit.

A small diamond stickpin held his patterned tie in place. Sideburns reached

below his ears and his hair grew long on the back of his neck. Long, thick

eyebrows climbed up and outward over deep-set eyes. There was a resemblance to

Jimmy Cagney, the actor.

The only obvious throwback to his North Carolina upbringing

is the way he says “can’t”—a word he doesn’t use often. When he does, he says,

“cain’t.”

Park said he is looking for more small newspapers,

particularly in North Carolina—“a part of my heart is in North Carolina—but

it’s awfully hard to find any good newspapers for sale there.”12 The reference

to newspapers in hand reminds me of another story about my father’s voracious

newspaper consumption, told to me by Stewart Underwood years after my father

passed away. The question arises as to what to do with all that newsprint once

you are done with it with no wastebasket handy. My father’s simple solution, as

you have heard, was to get rid of it wherever he was, whether into lakes,

pastures, under restaurant tables or, in this case, out of the windows of a

private airplane. Underwood told me when my father chartered short business

trips on small planes, where he had to sit in the cockpit beside the pilot, the

windows could be opened since they were flying low. Out went the newspapers

into the air until the pilot, after it happened a third time, pointed out that

the plane could crash since they could end up catching on the rudders.

Later, I remember flying with him on larger charters where

there were so many slippery sections of newsprint on the floor you had to hold

on to the back of the seats or whatever you could when you were leaving the

plane to keep your feet from sliding out from under you.

Being intent, focused and demanding, my father was under

continuous stress. But he thrived on it. He told the Cornell graduate business

students, “The number one thing is to be honest. And you have to learn how to

handle pressure. You’re not going to get anywhere unless you can deal with

stress. But stress can be the greatest thing in the world. It can make you do

things you didn’t think you could do.”

I don’t think I need to point out that his stress was also

imposed on others, and he did a good job of keeping us under it. He even installed

a buzzer, connected to his desk, in his secretary’s bathroom. The buzzer would

go off just about every time his secretary disappeared from her desk.

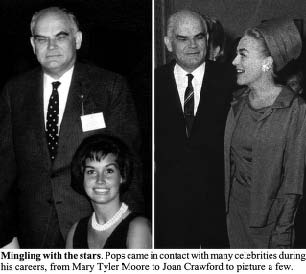

In social situations, my father had a great sense of humor.

He allowed himself to loosen up. Sometimes too much. He enjoyed that first

drink, and the second, and if my mother didn’t catch him, a third or more. Al

Neuharth said, “It was a delight to be with him socially. He remembers the

little niceties, [and] when it’s appropriate to…say nice things, to offer

congratulations.”

But sometimes his kidding meant trouble for others. There

were times you couldn’t get him to give a straight answer. I remember when my

wife and I were invited to a dinner party at his house on a cold November

evening in the early 1970s. Tetlow called him and asked what she should wear.

He told her it would be a churchy-type group, so she dressed in staid, tweedy

attire. We arrived before most of the guests, expecting the group to be dressed

as my father indicated.

She remembers sitting on the piano bench with a clear view

of the front door. As guests arrived she noticed their attire was much more

glamorous. Then a beautiful blonde apparition came through the door dressed to

the nines, and she thought how much she looked like Ginger Rogers.

One of my father’s guests ran Ithaca Industries, at the time

the nation’s largest private-label manufacturer of pantyhose. He was the

supplier for J.C. Penney, which in 1972 signed a seven-year deal with a

celebrity to act as a traveling fashion consultant. The vision at the party

was, indeed, the lovely Ginger Rogers, and Tetlow vowed never to take fashion

advice from Pops again.

It should be noted that Ginger was a lot tougher than she

looked since Johnnie took her skeet shooting with the good old boys the next

day. It wasn’t only her looks that left them with their mouths hanging open.

Johnnie said she was a crack shot.

I suspect that it was my father’s keen, and sometimes

warped, sense of humor that helped sustain him because, although he loved what

he did, he took over far too many responsibilities at any given time. Of course

we know, as J.J. Procter said, “There are things of deadly earnest that can

only be safely mentioned under cover of a joke,” but I think his sense of humor

carried him through. He once jokingly told the NC State student body that

friends at the college said that after he left North Carolina on April Fools

Day in 1942 “North Carolina really started to move.”

His last assistant, Jack Claiborne, said that along with his

love for work, Pops had “a dry and droll wit.” Claiborne remembered when he

hadn’t got the seating arrangements made in time for the company’s management

meeting one January in Raleigh, NC, so there was some confusion. Everybody got

to sit where they wanted and some people liked that. At the end, Roy glossed it

all over by saying, “We had a good time this year. Next year we’ll mess it all

up by being organized.”

It was seldom that Pops was at a loss for words, but there

were exceptions. One day our fourth floor receptionist came to work dressed in

a cowboy outfit complete with boots, bandana and hat. On his way up to his

office, the elevator stopped at the fourth floor to let off a passenger and my

father’s mouth fell open at her unusual, eye-catching apparel. For a moment

people say he was speechless, but as the elevator doors slowly closed, he was

heard to say “Howdy.”

Another story he told on himself was wanting an expensive

computer watch when digital watches were first introduced. For some time, he

had his eye on one at Tiffany’s in New York City. “My wife thought it was too

expensive so I bought it for myself and had it engraved: ‘To RHP from RHP,

Christmas 1975.’ ” Later, Pops said, Dottie told him the message should have

read: “To RHP from your closest friend.”

As Dottie said when asked what it was like living with Pops,

“Life with Roy has been fun, hard and breathless.” Yes—and I could add a word

or two to that.