POPS’S HOBBIES

As for hobbies, Dumbell reported in the Charlotte Observer

that he “voraciously reads fiction and nonfiction, magazines, newspapers and

technical journals, shows his cars, enjoys deepsea fishing and raises peacocks

and dogs at home.” Actually he read very little fiction. He was an avid reader,

however, of business magazines, and you already know how he devoured

newspapers. He did enjoy deep-sea fishing; I went fishing with him in the Gulf

Stream off Florida, as well as in lakes in Canada on a few rare occasions.

When it came to his raising dogs, he just collected them,

telling Dumbell, “Some are Bedlingtons, and some are just mutts we picked up

off the street.” As far as raising peacocks, it was mainly my mother’s

interest, not his. There was nothing wrong with peacocks wandering around the

yard, but he took little interest, other than visual, in the birds.

Other collections were a different story. As Treva Jones

reported in the News & Observer in 1997, in addition to radio, television

stations and newspapers, Park collected watches, reported as “fine gold

watches,” as well as antique cars. The paper said he had “more than half a

hundred watches and more than a dozen classic cars.” Business reporter John

Byrd wrote in the Winston-Salem Journal in 1983 that during his interview, Roy

Park sat on the edge of the sofa, gold cuff links in his sleeves and a diamond

pin in his tie. On his right wrist Park wore a watch with twin dials, a

Christmas gift from his wife, Dorothy, that helps him keep up with time zones

when he travels.

On his left wrist was a gold watch-calculator that,

conceivably, he could use to calculate his fortune or figure the worth of a

newspaper he’d like to buy. He bought the watch at Tiffany’s in New York, after

Dorothy had seen it but, quite inconceivably, told him she couldn’t afford it. From

his pocket he pulled an English-made watch disguised as a cigarette lighter,

another Christmas gift. And in the desk drawer was a chiming watch that he had

used as an alarm that morning.13 As to cars, actually, he had sixteen “vintage

cars,” and some weren’t so vintage. Reposing under individually tailored

dust-covers in his garage, among others, was a 1940 Packard Darrin convertible,

a ten-year-old Lincoln Continental, a Nash-Healey, two Jaguars, an Auburn and a

1929 Duesenberg. The Jaguars were vintage but not antique, and the boattailed

Auburn was a replica formerly owned by Rod Serling.

He also had a Bentley that he picked up new at the factory

in London twenty or twenty-five years ago, a supercharged 1936 Cord “and a few

others.” With fewer than 2,000 miles on it, the Bentley is “for all practical

purposes brand-new,” he said. But his favorite was a 1929 Duesenberg Model J

roadster, one of only 480 built. That automobile almost invariably took first

place in every show it entered. It was judged the most popular of 90 entries in

the Grand Prix Concours D’Elegance at Watkins Glen and was judged the best of

152 shown at the New York State Fair. He enjoyed an occasional ride in this car

which according to a brass medal in the car was capable of cruising at over 100

miles per hour, “If you could find a good smooth road,” my father said.

John Watlington, Jr., former chairman of Wachovia Bank and

Trust Company’s executive committee, was an old friend of Pops. He told about

the time he drove the Duesenberg, “Roy asked me if I wanted to drive it. I had

no idea at that time what it was worth and I said sure. I noticed Roy didn’t

seem very enthusiastic, but I drove it around the block. When I got back, he

walked all around the car and carefully checked it out. When he saw I hadn’t

put a scratch on it, he sighed and relaxed. When I found what that car was

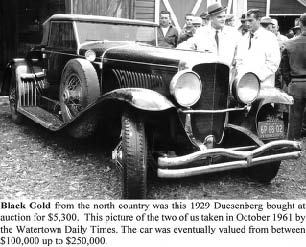

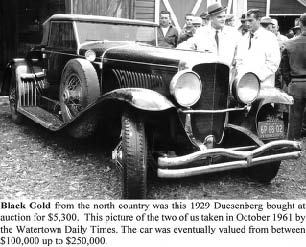

worth—one hundred thousand dollars!—I nearly died!” The Duesenberg brings back

happy memories of an auction my father went to in northern New York attended by

200 to 300 people. It’s ironic that I went with Pops when he bought it, which

was the only occasion I was with him where he pulled off one of his many deals.

He bought a car for $5,300 in 1961, and Skip Marketti, executive director of

the Auburn-Cord-Duesenberg Museum in Auburn, IN, valued the car at up to

$250,000 some twenty years later. Right after I attended the auction with Pops,

a story appeared under the headline, duesenBerg roAdster Brings $5,300 At sALe

in the Watertown Daily Times on Friday, October 27, 1961. The subhead said, roy

h. pArk, ithACA, purChAses CAr—300 Attend AuCtion At CArthAge.

Staff writer John W. Overacker started the article with,

“Sold to that gentleman for $5,300.” So Auctioneer Edward J. Madden, trust

officer, Watertown National Bank, announced the sale of the 1929 J Model

Duesenberg roadster to Roy H. Park of Ithaca, head of Duncan Hines Institute,

at the auction conducted Thursday afternoon on the island of Carthage.

Approximately 300 persons crowded on the island for the

sale. They were from all over New York State, from Connecticut, New Jersey,

Ohio, Pennsylvania and Michigan. And those interested were principally Cord and

Duesenberg “buffs,” here to again witness that a “classic” car’s appeal never

dies.

When a J Model Duesenberg on its 142-inch or 153.50-inch

chassis went quietly down the road, all of its 300-odd horsepower purring like

a kitten, handling like a racing car, something happened to each person who saw

it. It was a car designed for the “big rich” and the “big rich” bought it. The

chassis alone of these cars went for something like $8,500 to $9,500 and when

personal body designs were added the total tab often hits as high as $20,000.

One of the most interested persons to attend this auction

was Gordon M. Buehrig, who designed the original Cord automobile, who was with

Cord when he purchased Duesenberg and designed several J models, and SJ models,

including one for Gary Cooper. Mr. Buehrig was later with the engineering and

research staff of the Ford Motor Company, Detroit, Michigan.

Mr. Buehrig had come to Carthage to bid on the Cord, a car

which he had not owned for 20 years. He decided not to bid on it, feeling that

the auction was “a bit too rich for my blood. I knew this when the J Duesenberg

went for $5,300. And I have my eye on a Duesenberg which I may buy at some

future date.”

As for my father’s purchase, Overacker reported, It was the

consensus of the Duesenberg buffs that Mr.

Park had not overpaid. Asked how much more money would be

needed to put the roadster into good condition, several answers were given but

they averaged out between $3,000 to $5,000. All insisted that six whitewall

tires would have to be purchased, and that would run approximately $750. A

valve job by Hoe would run $400 more. Some thought that as much as $2,000 would

be needed to do a good chrome job and then there were additional odds and ends,

such as upholstery, paint, dashboard, etc.

All the work was done in short order by Phil Soyring, my

father’s auto mechanic, and the car won award after award, year after year.

When Pops died, he left it in his will to Soyring, who had taken care of all

his antique cars, and the rest of the cars in his collection were sold or given

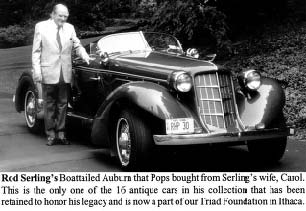

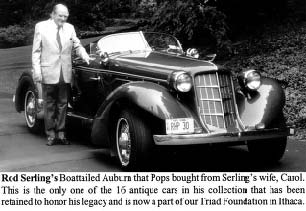

away. Only one or two remain with the family today. The one I kept for our

foundation is not even an antique but has an interesting history. It’s the

boattailed Auburn replica that was custom-built for Rod Serling, who had a home

in Ithaca and whom I got to know quite well. I was, and as you can guess by my

familiarity with his TV episodes, still am a fan of Serling’s Twilight Zone.

He and his wife, Carol, came to my house for a cocktail

party and I attended a number of other parties with them. After he died, Carol

called me to say she had received offers for the car in California and asked me

to check with my father to see if the offers were fair. I suspect she knew my

father would personally be interested because of her husband’s connection with

Ithaca College, and of course Pops ended up buying it.