BACK TO OUTDOOR

At the time I returned, the Park Outdoor Advertising

companies maintained more than 3,000 poster and paint units in upstate New York

from the St. Lawrence River to Lake Erie, and across northern Pennsylvania. The

companies served key markets of Utica, Rome, Binghamton, Elmira, Jamestown,

Olean and Dunkirk in New York; and Scranton, Wilkes-Barre, Towanda, Sayre,

Bradford, Warren and Oil City in Pennsylvania.

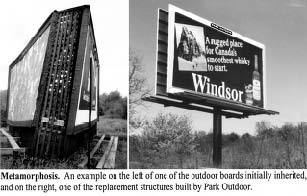

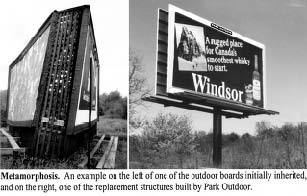

This time my father agreed with Babcock and me to commit

substantial amounts of money to modernize the Park Outdoor poster and paint

locations, “as Park moves dynamically into the ’80s with new experienced and

professional management across the board.” He had already allowed, in the

Scranton division, the installation of new trim on the poster panels, and in

other branches, the installation of new unitized panels, white baked-enamel

trim kits and new fluorescent lighting.

We had gone to prepasted posting in our divisions by this

time and we created a new rotary paint program in Scranton. My father had

allowed me to double our construction crews to expedite the work and provide

continuous upgrading of the appearance of our outdoor units. I also had

convinced him to join in the Traffic Audit Bureau (TAB) program, and he agreed

to pay the cost of having all of our branches being audited by TAB to provide

accurate circulation figures for our locations. We also were able to join the

New York and Pennsylvania Outdoor Associations as well as the Institute of

Outdoor Advertising and the Outdoor Advertising Association of America (OAAA).

My father promised: “After total modernization is completed,

we will continue into the decade with unipole poster and paint structures, new

rotary paint programs in every branch and halophane lighting on our paint

units.” With this upgrading in progress, we began an active new leasing program

and worked closely at the local levels with planning and zoning officials to

protect our place in the market to provide the best possible coverage.

In putting me back in charge, my father also knew that

although I had been out of the New York City circuit for six years, I still had

my contacts with the large national accounts, some of whom went back to my J.

Walter Thompson days.

One of the major reasons for stagnant growth while I was out

of the outdoor picture was the decline in our share of the national cigarette

business. Competition had moved into Scranton, financed by one of the cigarette

companies because our boards looked so bad. Another major tobacco company had

pulled its business.

Slowly but surely the national tobacco companies who had

come back to Park Outdoor in Scranton after the massive upgrading we had done

in the plant began to expand with us in our central New York markets. R.J.

Reynolds, Brown & Williamson, Liggett & Meyers, Lorillard, and American

Tobacco came back as key advertisers. Lorillard had been the most difficult to

bring back because it had been treated so badly during my absence. It took five

years before Lorillard gave Park Outdoor another chance. The field inspector

who was snubbed by my predecessor became the media director of the company, and

he had a long memory. It was only after others he had brought up through the

ranks recognized that they could trust our people that Lorillard began to

expand into a major factor with our company.

During this time, we also expanded our inventory. In 1986 we

built some boards in the Syracuse market and then extended the coverage with

the purchase of ten bulletin faces. We also negotiated for some bulletin

locations on I-81 leading into Syracuse on the Onondaga Indian Reservation. Our

lease manager met with the thirteen chiefs in a real longhouse, smoked the appropriate

pipes and came to an agreement for several locations on the reservation. The

deal was signed, it would bring good money to the reservation, and all was in

order.

That’s when Dennis Banks, a fugitive from justice, came to

the reservation to hide out from the authorities.

About the time the construction for the first unit started,

the construction team from Scranton found themselves, along with our lease

manager, surrounded by Indian braves with chains, chainsaws and shotguns. The

Indians had damaged the construction machinery and put sugar in the gas tanks.

Then the hostility accelerated. I remember receiving a call from a phone booth

on the reservation from our lease manager describing the situation and asking

what he should do. My reply was “Get the hell out of there.”

I found out later that Banks had stirred up the tribe. The

braves overruled the agreement made by the chiefs, and white men were driven

off the reservation.

I was amazed when, later, the chiefs returned the thousands

of dollars of lease payments we had given them in advance, right down to the

penny, but I still feel anguish as I ride up I-81 knowing a belowground pad for

the structure still exists at the location where our first eighty-foot

structure was to go up under the agreement. Later, the tribe took over the

other boards owned by our competition that already existed on the reservation,

and the units still carry graffiti to I-81 travelers today.

It should be noted that Banks later was sentenced to life

imprisonment for the 1999 murder of a nineteen-year-old. While I was with Park

Broadcasting, it is interesting that I remained in the same corner office on

the fourth floor of Terrace Hill that I had when I first ran outdoor, but the

outdoor division had been moved from the second floor to the basement. So I

moved into the dungeon quarters which, aside from being damp and moldy, had no

drop ceilings to cover the overhead piping, and natural light only from window

wells. I quickly renovated the space the best I could, but many pipes hung too

low to be covered.

I installed cheap carpeting over the cement floors and built

out offices to give individual privacy in what used to be a bullpen. The only

separate office space before I moved down had belonged to the former general

manager, and was set up by him to keep an eye on the workforce in the bullpen

through a window.

We put up with live animals, including chickens, in the

window wells, and either freezing from being below ground or burning up from

our location next to the building’s main furnace. And I recall with some

embarrassment national clients stumbling down the musty steps to the basement

side entrance. They could see what my father thought about the outdoor

division. And I remember the day when my six-year old niece came to the basement

to visit. After open-mouthed silence, she looked at the exposed pipes in the

ceiling and asked, “Doesn’t Grandpops like you?” At any rate, 1982–83 were

turnaround years, going from a loss of over half a million because of the

problems and huge maintenance expenses I re-inherited in 1982 to a small

$40,000 operating profit in 1983. Which was a good thing since the improvement

on the outdoor bottom line helped to contribute to the overall fiscal health of

Pops’s empire, which at this time included over 30 newspapers along with

television and radio stations. It was time for a great leap forward.

(Back to Contents)