A MERRY SCOUT

He didn’t belong to any patrol—he wasn’t a real scout at all, but it wasn’t Davy’s fault. He was only nine and a half, you see, and that meant two years and six months of waiting—oh, such long waiting it seemed to Davy—before he could wear the coveted arrow-head badge of the tenderfoot scout and go hiking and camping like big Cousin Fred.

That is how the figures stood late in December. It was the summer before, at Grandfather’s, that Davy had first begun counting the time until he should be twelve. There, at the farm, he had met Cousin Fred. Fred was sixteen years old, a first-class scout, patrol leader in his home town, and a winner of the life-saving merit badge. But he had never felt too big to take Davy for a Sunday hike over the hills, relating thrilling tales of scout camp life and wood-craft; telling all about scout law, with its twelve hard things every scout must be and the daily good turn every scout must do; explaining the different badges, the oath, and the salute. What wonder that Davy wanted to be a scout most of anything in the world!

Shortly after his return in the autumn Davy determined to take matters into his own hands. Accordingly, one day, standing before his looking-glass and raising his right hand, palm to the front, he solemnly swore to the oath, all by himself; then he pinned under his jacket, right over his heart, a secret badge of his own designing. There he had worn it ever since, and considered himself as honor-bound to the oath as any scout living.

Standing before his looking-glass, Davy swore to the oath, by himself

It was now two days before Christmas. There had been a snowstorm, clearing about noon. Davy had hailed it with whoops of delight. Now, by shoveling walks, he might earn money to get a Christmas present for Mother and Father, after all. It could not be the magnificent azalea and real leather pocketbook he had first dreamed of—that had been on the expectation of at least six snowstorms; but there was a gay little Jerusalem cherry tree for Mother, and for Dad a beauty of a tie, red and green changeable. Davy had selected them days ago—all he was waiting for was a job. What luck it should be Saturday and no school!

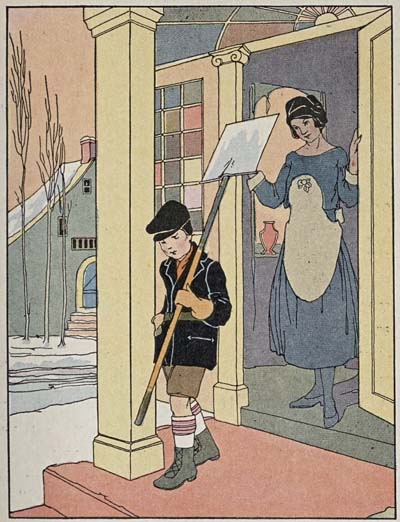

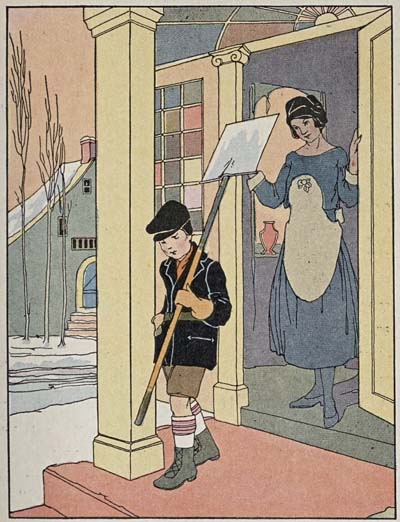

For one reason or another, nobody seemed to need Davy’s services

When the one o’clock whistle blew, Davy and his snow shovel were well on their way, bound for an attractive-looking corner house out on the avenue—corner houses were twice the job of ordinary places. Davy pressed the bell button confidently. A sour-looking maid opened the door an inch, snapped out “No,” and banged it to before Davy could get out a word. He stood staring at the door for a moment, his mouth still open, but a minute later he was striding across the street to the opposite corner, once more wearing his sturdy scout smile. There, however, they kept a hired man; next door, a big boy was already at work. For one reason or another, nobody seemed to need Davy’s services, and it began to look as if Daddy and Mother might not get their Christmas gifts at all; only, Davy was determined. At last a nice little lady twinkled “yes” over her spectacles. But Davy was only on his third contract, with a shortage of ten cents staring him in the face, when the town clock struck four.

“Well, I declare, you work as if you meant business!” A jolly old man paused at Davy’s elbow. “Come up to number seventy Lexington Avenue—electric light in front—and I’ll give you a job. My pay is thirty cents. If you aren’t there by a quarter of five, I’ll take it you’ve struck something nearer by and do it myself.”

“Oh, I’ll be there, all right. Thank you, sir!” Davy’s spirits rose to the crown of his cap. The necktie and cherry tree were in sight again—and a box of candy too.

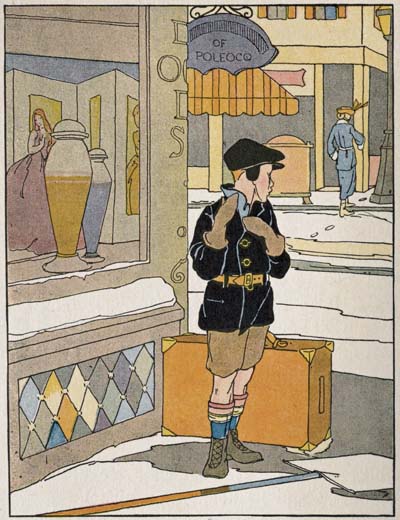

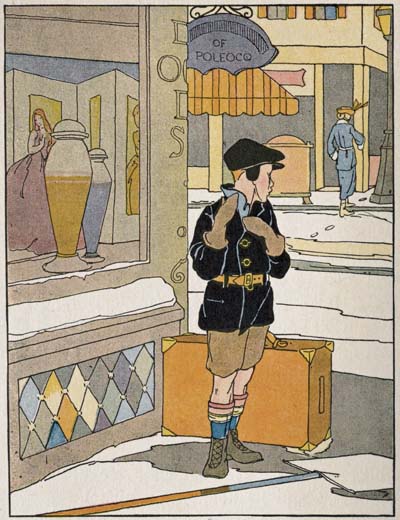

Davy nearly ran down a young lady dashing along with a suitcase and

an umbrella, in a frantic effort to overtake a passing trolley

Fifteen minutes later he was scuttling out to Lexington Avenue. As he was crossing the street, a block or two from the railroad station, he nearly ran down a young lady dashing along with a suitcase, a handbag, and an umbrella, in a frantic effort to overtake a passing trolley.

“Hey, there, hey!” yelled Davy, but the car whizzed right along.

“Oh, dear!” panted the young lady, dropping her suit case. “I’ve lost it, and there won’t be another Fletcher Avenue car for fifteen minutes.” She looked as if about to drop, herself, and Davy involuntarily stretched out a small hand to steady her.

“Thank you,” she gasped. “I do feel a little shaky, running with this heavy luggage. I believe I’ll go around the corner to the drug store and get something hot—provided I can secure a trusty young man to watch my suitcase.” She smiled confidently down into Davy’s honest face. “I’ll be back in ten minutes, in time to catch the next car.”

“Oh, you can trust me, sure!” Davy smiled back. A scout has to be helpful and courteous, especially to people in trouble.

“And you’ll stay right here with it and not let anyone touch it? It contains all my Christmas presents, you see.”

Davy promised with his hand over his badge, but of course she couldn’t see that away under his jacket!

He watched her anxiously as she crossed the street and turned the corner. Then he sat down on one end of the bag, his snow shovel at his feet, and began to consider.

It was now twenty-two minutes after four by the clock in the little tailor shop at his left, and he must meet his appointment at a quarter of five or lose his job. Luckily, he had planned to get there ahead of time—and she would be back in ten minutes—so he’d keep his date all right.

Trinity chimes pealed the half-hour. Eight minutes gone, and she hadn’t returned.

Now in the distance appeared a Fletcher Avenue car—her car, that she would surely be back to take! It approached, passed—and she hadn’t come. Something must have happened! If he could only go around the corner and find out—but there was his promise.

Another five minutes gone—why didn’t she come? He might still make it if he ran.

The chimes rang out a quarter of five! It was all up now about the job, and he was still ten cents short on his Christmas fund, for he could not take a tip from the lady—a scout may never accept pay for a good turn. A chill wind was coming up, and it was growing darker and darker on the lonely corner. Davy stood up and stamped his feet to get out the numbness. But a scout has to be cheerful, no matter what, and he tried to whistle.

The town clock struck five. The little tailor came out of his little shop, rattled his big key in his door, and was gone, leaving Davy lonesomer than ever. He brushed his eyes with his coat sleeve. A scout cry? Never! But he was so cold and lonesome and disappointed about the job! He hadn’t thought that being a scout would be just like this.

Then suddenly, clearer than the chimes, he seemed to hear Cousin Fred’s cheerful voice again, reciting their favorite passage from the law: “A scout is brave. He has the courage to face danger in spite of fear.” And Davy knew, for sure, that he wasn’t going to desert his post, no, not even if it meant an all-night watch! He turned up his coat collar and with better success started whistling again, keeping time with his toes as he paced up and down.

“Hello, pard, waitin’ fer yer airship?” A burly young tough whom Davy had noticed hanging around the opposite corner swaggered up with a cigarette in his mouth. “What yer got there? Nuggets or bombs?” giving the suitcase a kick. “Aw, say,” he added, with a crafty smile, “I’ll mind it whilst yer beat it to Jakey’s fer a bag o’ peanuts,” and he held out a nickel.

Davy turned up his coat collar and started whistling

“Oh, no, thank you.” Davy sat down on the suitcase in a hurry. “I couldn’t think of leaving it to anyone, not even somebody I know. I promised her, you see—the young lady—to keep it till she came back. It’s got all her Christmas presents in it!” Davy added proudly.

The ruffian’s eyes narrowed. He cunningly changed his tactics. “Say, kid, what did she look like—her that belongs to the bag?”

“All kind o’ brown clothes and pretty and dreadful white in the face. Maybe you’ve seen her?” wistfully.

“Well, what do yer know!” Davy felt his arm clutched tight. “Believe me, pard, that young lady’s a pertic’ler friend o’ mine! And if you’ll jest remove yerself from her trunk there, I’ll be dee-lighted to fetch it to her. Here, I’ll stand fer her tip,” trying to slip a coin into Davy’s hand.

“No, sir!” Davy set his jaw fast and plumped down his little body more protectingly than ever over his charge.

“Aw, yer won’t, won’t yer? We’ll see,” sneered the ruffian, casting a furtive glance to right and left.

In an agony Davy followed his glance, but no help was in sight—save an approaching trolley, and that probably wouldn’t stop. Oh, if only some one would come, or if he were only bigger, or had a magic sling like that David of old! But no, all unarmed he must meet his giant Goliath. Was ever a true scout up against heavier odds? Then, in his dire need, he seemed to hear Cousin Fred’s voice again, “A scout has the courage ... to stand up for the right ... against the threats of enemies ... and defeat does not down him.”

Davy braced himself for whatever might come—and it came promptly. A sharp wrench, a vicious punch, and the suitcase was in the hands of the enemy, and Davy flattened on the ground, well-nigh winded. It was a black moment for the brave little scout. Everything lost—and what would she think? And he had tried so hard!

“Aw, yer won’t, won’t yer? We’ll see,” sneered the ruffian

Then—Ah, the trusty snow shovel, Davy’s ally that hadn’t been reckoned on. Trip-ity-rip! Over it went the enemy with an ugly growl, sprawling into the gutter!

And the car had stopped, depositing a broad-shouldered young man who saw what had occurred and was now making rapid strides toward Davy. The ruffian, scenting trouble, picked himself up, and limped a double-quick retreat through the shadow and around the corner—without the bag!

“Well, well, here you are, standing by your guns, just as she said you’d be!” The young man was addressing Davy, who had managed to get on his legs once more and regain his charge. “Say, but you’re game all right!” At the word of appreciation and the comradely slap on his shoulder, Davy suddenly didn’t mind any more about the long waiting, losing the job, and having the wind knocked out of him.

“You’re looking pretty white about the gills, though,” the big young man’s voice was very kind. “Beastly long ten minutes, wasn’t it? She didn’t count on fainting, you see, and that sort of thing. She’s my sister—teaches in the South—was going to spring a surprise on the family by coming home for the holidays. Here, I’ll take that ark off your hands and start you homeward. Your folks’ll be getting worried about you.”

Ah, the trusty snow shovel, trip-ity-rip! Over it went the enemy

Oh, how Davy longed to accept the proffered release! But no, “I—I—I can’t,” he stammered. “I promised, and a scout has to keep his word.” Oh, it was hard to say “no” to this friendly young man. It took almost more courage than fighting the ruffian.

“Well, that’s a good one on me!” The big young man turned away his face to save Davy’s feelings. “A scout, did I hear you say?” He was quite serious now. “But you’re some way short of twelve?”

Then, of course, Davy had to tell about the secret badge, who he was, where he lived, Cousin Fred, and the encounter with the ruffian.

“Come, give us your hand, brother scout. You’re the real article, certificate or no certificate!” Davy’s small, mittened palm was taken in a mighty grip. “Now stand on the suitcase and look here”—the big young man opened his greatcoat—“on my sleeve, can you see?” taking out a pocket flashlight.

Davy saw. The badge of the scout master—a sure guarantee of all that was honorable and loyal, trustworthy and brave. It was like the coming of the Prince in fairy tales. Davy’s eyes glowed. Words failed him, but off came his right red mitten and three fingers were raised to his forehead in reverent salute. Then he quietly slipped from the suitcase, and, the weary watch over at last, joyfully resigned his charge into lawful hands.

“I say! you’re a dandy little scout, just the kind I’m looking for. And if only I were a magician, I’d hustle those next three birthdays of yours along in no time at all. But here’s your car—you’ll hear from us later. Good-by!” And with a parting slap for Davy and a nickel to the conductor, the scout master was gone.

On Christmas morning there came a package and a letter for Davy, both in the same unfamiliar hand. The package contained a most wonderful book, and the letter read:

MY DEAR LITTLE MERRY SCOUT:

Yes, that is what I have named you, for where would there have been any Merry Christmas for me but for your valiant defense of my precious bag! I am so sorry for what you had to endure on my behalf, but I am very happy to add to my acquaintance one more person who can be trusted, whatever the cost to him. Surely, never was a real, truly boy scout more faithful to his oath than my little scout of the secret order.

I hope you will enjoy the Animal Book and Camp-Fire Stories, by Dan Beard, National Scout Commissioner, which my brother and I are sending you as a small token of our gratitude.

We are planning to see you very soon.

Most cordially your friend,

AGATHA ALDEN.

“Gee!” gasped Davy, turning rapturously from letter to book and back to letter again. “But any scout would have had to do it, wouldn’t he, Dad?”

Father, admiring his new Christmas tie before the sideboard mirror, smiled down into Davy’s earnest face reflected therein. “I should certainly say he would, my son,” he agreed, without hesitation. But the eyes he turned to Mother, across the room, were brimming over with pride.

On Christmas morning there came a package and a letter for Davy

“Our little Merry Christmas Scout,” softly responded Mother, who was tending a gay little Jerusalem cherry tree at the window. Sometimes there are bargains, you know, the last thing before Christmas, and so Davy’s ten-cent shortage didn’t matter, after all!