ROBERT’S ADVENTURE

“Good-by, Robert,” called Mother, as she and Father drove off for the city one summer afternoon. “Don’t forget to fill the wood box, dear, and to feed the chickens.”

“Good-by,” answered the boy from the stone wall, without looking up.

Robert was discontented. He was tired of filling the wood box and feeding the chickens every day, and for only five cents a week. Five cents a week! Yes, that was all he had to spend for candy, marbles, and everything, while Timmie Marsh, who lived down the road, had a nickel about every day, and he never had to work at all.

Robert had been thinking and thinking what could be done about it, and at last he had made up his mind. He would go to Blakeville that very afternoon to old Nurse Tucker’s. He could walk four miles easily, and Nurse would be so glad to see him.

“Of course,” he said to himself, “I’ll write to Mother, so she’ll know I’m not drowned or anything. And I’ll tell her how Nurse gives me five cents for candy every day—’course she will—and how I don’t have to do any work, either. Then won’t Daddy come for me quick and say if I’ll only go back with him, I needn’t bring in the wood or feed the chickens or do anything unless I feel like it, and I can have all the money I want, besides!”

And now, as the buckboard vanished in the distance, Robert turned toward the house to carry out his plan. He could hear Mandy, the hired girl, singing at her work as he tiptoed cautiously in at the wood-shed door and up to his room.

After giving his hair one hasty stroke with the brush and putting on his Sunday shoes and stockings, he considered his toilet completed and was soon stealing out of the wood shed again, unobserved by Mandy.

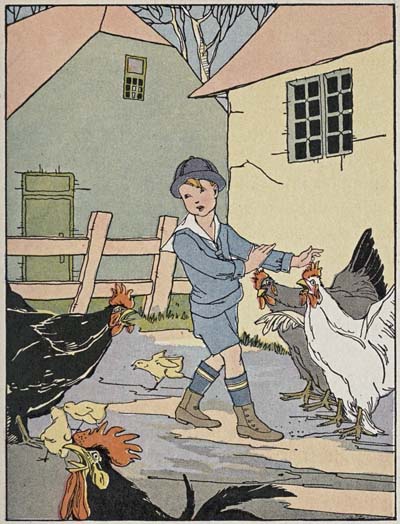

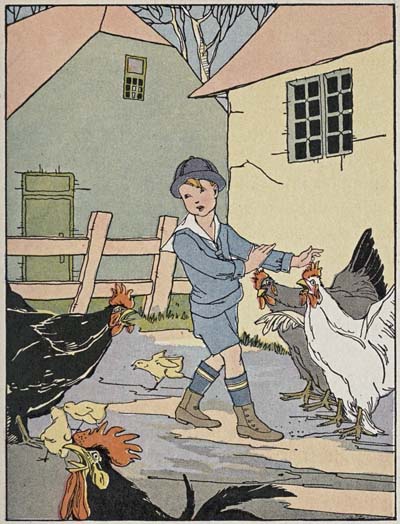

A moment later Robert was skulking through the barnyard, making a bee line for the blueberry lot and the turnpike. But what made the chickens act so queerly? Mrs. Bantam, with her head cocked on one side, eyed him suspiciously as he crept along, while the great white rooster flew upon the coop and screamed right out, so loud that Robert feared the whole village would hear. “What-you-going-to-do-oo? What-you-going-to-do-oo?” Robert did not think best to answer, but was only more eager than ever to move on his journey.

He had no sooner struck the blueberry lot, however, than Lady Ann, the Jersey cow, started for him, and, poking out her head, exclaimed in mild surprise, “Oo-oo! oo-oo!”

“What-you-going-to-do-oo? What-you-going-to-do-oo?”

And he had barely reached the road, when, to cap the climax, the sheep from the stony pasture across the way began to chide him. “Ba-ad! Ba-ad!” they bleated.

“No, I’m not bad, either!” cried Robert almost in tears. Here he had gone cross-lots purposely to escape the villagers and now the animals were all after him! And, stuffing his fingers in his ears, he began to run.

The summer sun was blazing; still Robert kept on, though with ever-slackening speed, meeting no one but a stray dog or two and an occasional ox-team with its sleepy driver. At length he came to a big sign post which read:

BLAKEVILLE 3 MILES

“P’r’aps I’d better sit down a minute,” he said to himself. “I’m not tired, of course, and my shoes don’t hurt—only just a little bit. I guess there won’t be anybody to catch me ’way out here.” And as he sat rubbing his hands over the shoes that did not hurt, he encouraged himself with visions of the candy counter at Nurse’s village store.

“Why, Robert, little man, what are you doing so far from home?” There was no escaping an answer this time, for it was Mrs. Bronson, the minister’s wife, who stood before him.

“O—er, I’m—er going for a walk, Mrs. Bronson,” he stammered, jumping up; and, taking off his cap, he turned on his heel and started on again, never once daring to look behind.

But the Sunday shoes were soon pinching in good earnest. He could stand them no longer, so he pulled them off, and, swinging them on his shoulder, went on in his stocking feet.

Uphill and downhill he trudged. How hot the sun was! And how tired and bruised his poor feet were getting!

“I guess I’ll take another little rest,” he said as he limped across the road. “It’s nice and shady here by the brook and I am some tired.”

Down upon the sweet green grass he lay. The candy counter at Blakeville was beginning to lose its charm, and—

Robert sat up in a sudden fright. A solemn voice was calling to him from the woods: “Bubby-gu-hum! Bubby-gu-hum!”

Robert turned fearfully, and there, on a stone in the brook, sat a great, blinking frog.

“I won’t go home, you naughty frog!” he cried. “I’m going to Nurse’s.” Then, ka-splash! and Mr. Frog had disappeared.

There was a queer buzzing in Robert’s head, and presently he was fast asleep in spite of himself.

The sun set. The little boy slept on. A cool breeze came up, and Robert tried to pull the bedclothes over him, but there weren’t any clothes to pull—and he awoke.

He sat up and looked around. What could it all mean? When finally it dawned upon him where he was, he set up a wail and then stood in bewilderment.

“I won’t go home, you naughty frog,” Robert cried

In a moment he started in fresh horror, hearing wheels close at hand.

“Supposing it’s gypsies,” he groaned, “and they should carry me off! Oh dear! Oh dear!”

Nearer came the wheels. There was no way of escape. All he could do was to drop down beside the road and keep so still maybe they’d think he was a log of wood.

Now he heard voices. There might be twenty of them. Twenty gypsies! Could it be they were going by without noticing him? Robert hardly dared to breathe.

“Whoa there! What’s this?”

A big man leaped from the team. Robert closed his eyes and tried to pray. But all that he could think of was, “Now I lay me,” and that would never do.

A lantern was flashed in his face. “Bless my stars, if it isn’t our own Robert!”

“O Daddy, Daddy!” sobbed a frightened little voice.

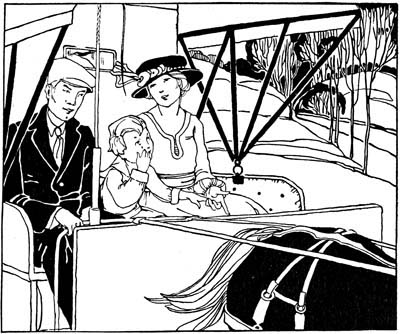

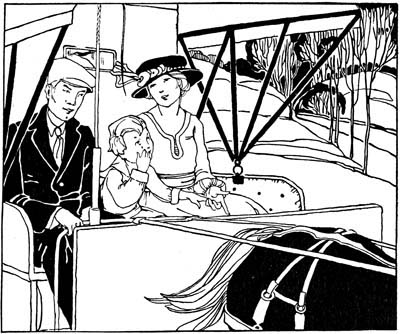

Two strong arms lifted the shivering little fellow and placed him in the buckboard right beside his own mother.

“Robert, Robert!” she cried tremulously. “How did you ever get way out here at this time of night?—and in your stocking feet!”

“Oh, Mother, I want to go home, and I’ll bring in the wood,

and feed the chickens”

“Oh, Mother, I was g-going to Nurse’s and my shoes hurt and I went to sleep, but I don’t want to go there any m-more. I want to go ho-home, and I’ll bring in the wood, and f-feed the chickens every day, and you needn’t give me any m-money at all!”

Then Mother, who was a wonderful magician, understood all about it.

“Oh,” she cried softly, “supposing we had gone home by the other road!”

But Father said, “Let’s see. It isn’t too late yet. Shan’t we turn around and carry him to Blakeville?”

“Oh, no, no!” pleaded Robert, clutching his father’s arm, “I want to go ho-ome.”

“Humph! you’ve really changed your mind then, have you? Well if that’s the case, we’ll jog right along. Get up, Daisy.”

And Robert, snuggled there up against Mother, so safe and warm, at that moment would not have changed places with any boy living; no, not even for all the candy in the Blakeville store!