RobinsonCrusoebyDanielDefoe.

Firstpublishedin1719.Thisisamodernisededitionwhichincludeschapter breaks.

Thisebookeditionwascreatedandpublishedby GlobalGreyonthe12thOctober 2021.

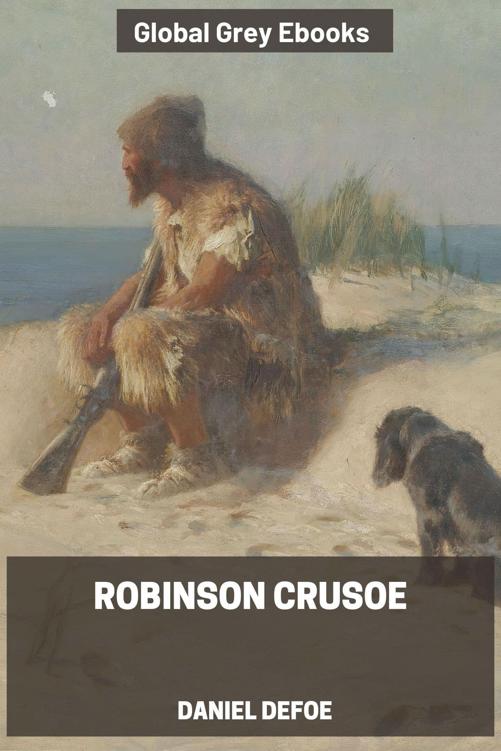

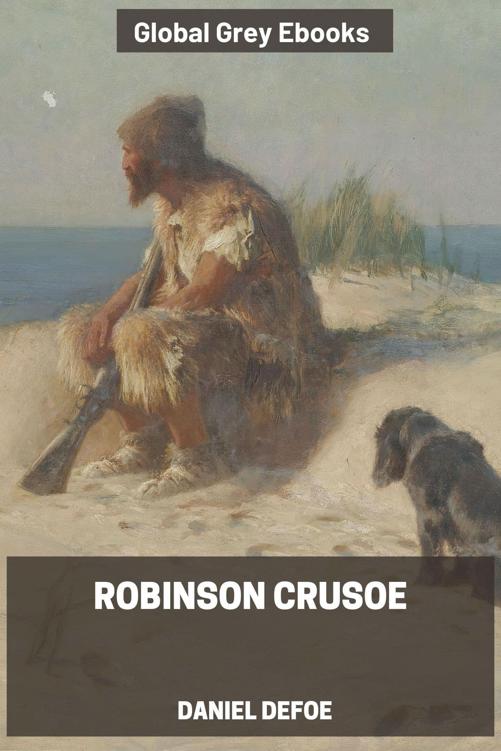

Theartworkusedforthecoveris‘Crusoe’

painted by John Charles Dollman.

This book can be found on the site here:

globalgreyebooks.com/robinson-crusoe-ebook.html

©Global Grey 2021

globalgreyebooks.com

Contents

1. StartInLife

2. SlaveryAndEscape

3. WreckedOnA DesertIsland

4. FirstWeeksOnThe Island

5. BuildsAHouse-TheJournal

6. IllAndConscience-Stricken

7. Agricultural Experience

8. SurveysHisPosition

9. ABoat

10. TamesGoats

11. FindsPrintOfMan’s FootOnTheSand

12. ACaveRetreat

13. WreckOfASpanishShip

14. ADream Realised

15. Friday’s Education

16. RescueOfPrisonersFromCannibals

17. VisitOfMutineers

18. TheShip Recovered

19. ReturnToEngland

20. FightBetween Friday AndABear

21. Sports Betting: Fundamentals and Innovations in the New Realities

1

1. StartInLife

I was born in the year 1632, in the city of York, of a good family, though not of that country, my father being a foreigner of Bremen, who settled first at Hull. He got a good estate by merchandise, and leaving off his trade lived afterward at York, from whence he had married my mother, whose relations were named Robinson, a good family in that country, and from whomIwascalledRobinsonKreutznear;butbytheusualcorruptionofwordsinEnglandwe are now called, nay, we call ourselves, and write our name, Crusoe, and so my companions always called me.

Ihadtwoelderbrothers,oneofwhichwaslieutenant-coloneltoanEnglishregimentoffoot in Flanders, formerly commanded by the famous Colonel Lockhart, and was killed at the battlenearDunkirkagainsttheSpaniards;whatbecameofmysecondbrotherIneverknew, any more than my father and mother did know what was become of me.

Being the third son of the family, and not bred to any trade, my head began to be filled very early with rambling thoughts. My father, who was very ancient, had given me a competent share of learning, as far as house-education and a country free school generally goes, and designed me for the law, but I would be satisfied with nothing but going to sea; and my inclination to this led me so strongly against the will, nay, the commands, of my father, and againstalltheentreatiesandpersuasionsofmymotherandotherfriends,thatthereseemedto be something fatal in that propension of nature tending directly to the life of misery which was to befall me.

My father, a wise and grave man, gave me serious and excellent counsel against what he foresawwasmydesign.Hecalledmeonemorningintohischamber,wherehewasconfined by the gout, and expostulated very warmly with me upon this subject. He asked me what reasons more than a mere wandering inclination I had for leaving my father’s house and my native country, where I might be well introduced, and had a prospect of raising my fortunes by application and industry, with a life of ease and pleasure. He told me it was for men of desperate fortunes on one hand, or of aspiring, superior fortunes on the other, who went abroad upon adventures, to rise by enterprise, and make themselves famous in undertakings ofanatureoutofthecommonroad;thatthesethingswere alleithertoofaraboveme,ortoo far below me; that mine was the middle state, or what might be called the upper station of low life, which he had found by long experience was the best state in the world, the most suited to human happiness, not exposed to the miseries and hardships, the labor and sufferings, of the mechanic part of mankind, and not embarrassed with the pride, luxury, ambition, and envy of the upper part of mankind.

He told me I might judge of the happiness of this state by one thing, viz., that this was the state of life which all other people envied; that kings have frequently lamented the miserable consequencesofbeingborntogreatthings,andwishedtheyhadbeenplacedinthemiddleof the two extremes, between the mean and the great; that the wise man gave his testimony to this as the just standard of true felicity, when he prayed to have neither poverty nor riches.

Hebid meobserveit, and Ishould always find that thecalamities oflife wereshared among theupperandlowerpartofmankind;butthatthemiddlestationhadthefewestdisastersand was not exposed to so many vicissitudes as the higher or lower part of mankind. Nay, they were not subjected to so many distempers and uneasiness either of body or mind as those were who,byviciousliving,luxury,andextravaganciesononehand,orby hardlabor,want of necessaries, and mean or insufficient diet on the other hand, bring distempers upon

2

themselves by the natural consequences of their way of living; that the middle station of life was calculated for all kind of virtues and all kind of enjoyments; that peace and plenty were the handmaids of a middle fortune; that temperance, moderation, quietness, health, society, all agreeable diversions, and all desirable pleasures, were the blessings attending the middle station of life; that this way men went silently and smoothly through the world, and comfortablyoutofit,notembarrassedwiththelaborsofthehandsorofthehead,notsoldto the life of slavery for daily bread, or harassed with perplexed circumstances, which rob the soul o f peace, and the body of rest; not enraged with the passion of envy, or secret burning lust of ambition for great things; but in easy circumstances sliding gently through the world, and sensibly tasting the sweets of living, without the bitter, feeling that they are happy, and learning by every day’s experience to know it more sensibly.

After this, he pressed me earnestly, and in the most affectionate manner, not to play the young man, not to precipitate myself into miseries which Nature and the station of life I was born in seemed to have provided against; that I was under no necessity of seeking my bread; thathewoulddowellfor me,andendeavortoentermefairlyintothestationoflifewhichhe had been just recommending to me; and that if I was not very easy and happy in the world it must be my mere fate or fault that must hinder it, and that he should have nothing to answer for, having thus discharged his duty in warning me against measures which he knew would be to my hurt; in a word, that as he would do very kind things for me if I would stay and settle at home as he directed, so he would not have so much hand in my misfortunes, as to give me any encouragement to go away. And to close all, he told me I had my elder brother for an example, to whom he had used the same earnest persuasions to keep him from going into the Low Country wars, but could not prevail, his young desires prompting him to run intothearmy,wherehewaskilled;andthoughhesaidhewouldnotceasetoprayforme,yet he would venture to say to me, that if I did take this foolish step, God would not bless me, and I would have leisure hereafter to reflect upon having neglected his counsel when there might be none to assist in my recovery.

Iobservedinthislastpartofhisdiscourse,which wastrulyprophetic,thoughIsupposemy father did not know it to be so himself — Isay, I observed the tears run down his face very plentifully, and especially when he spoke of my brother who was killed; and that when he spokeofmy having leisureto repent, and noneto assist me, hewas so moved that hebroke off the discourse, and told me his heart was so full he could say no more to me.

Iwassincerelyaffectedwiththisdiscourse,asindeedwhocouldbeotherwise?andIresolved not to think of going abroad any more, but to settle at home according to my father’s desire.

But alas! a few days wore it all off; and, in short, to prevent any of my father’s farther importunities,inafewweeksafterIresolvedtorunquiteawayfromhim.However, Ididnot act so hastily neither as my first heat of resolution prompted, but Itook my mother, at a time when I thought her a little pleasanter than ordinary, and told her that my thoughts were so entirely bent upon seeing the world that I should never settle to anything with resolution enough to go through with it, and my father had better give me his consent than force me to go without it; that I was now eighteen years old, which was too late to go apprentice to a trade, or clerk to an attorney; that I was sure if I did, I should never serve out my time, and I should certainly run away from my master before my time was out, and go to sea; and if she would speak to my father to let me go but one voyage abroad, if I came home again and did not like it, I would go no more, and I would promise by a double diligence to recover that time I had lost.

This put my mother into a great passion. She told me she knew it would be to no purpose to speaktomyfatheruponanysuchsubject;thatheknewtoowellwhatwasmyinteresttogive

3

hisconsenttoanythingsomuchformyhurt,and thatshewonderedhowIcouldthinkofany such thing after such a discourse as I had had with my father, and such kind and tender expressions as she knew my father had used to me; and that, in short, if I would ruin myself there was no help for me; but Imight depend I should never have their consent to it; that for her part, she should not have so much hand in my destruction, and I should never have it to say, that my mother was willing when my father was not.

Though my mother refused to move it to my father, yet, as I have heard afterwards, she reportedallthediscoursetohim,andthatmyfather,aftershowingagreatconcernatit,said toherwithasigh,“That boymightbehappyifhewouldstayathome,butifhegoesabroad he will be the miserablest wretch that was ever born: I can give no consent to it.”

It was not till almost a year after this that I broke loose, though in the meantime I continued obstinately deafto all proposals ofsettling to business, and frequently expostulating with my father and mother about their being so positively determined against what they knew my inclinations prompted me to. But being one day at Hull, where I went casually, and without any purpose of making an elopement that time; but I say, being there, and one of my companions being going by sea to London, in his father’s ship, and prompting me to go with them, with the common allurement of sea-faring men, viz., that it should cost me nothing for my passage, I consulted neither father nor mother any more, nor so much as sent them word of it; but leaving them to hear of it as they might, without asking God’s blessing, or my father’s,withoutanyconsiderationofcircumstancesorconsequences,andinanillhour,God knows, on the first of September, 1651, Iwent on board a ship bound for London. Never any young adventurer’s misfortunes, I believe began sooner, or continued longer than mine. The ship was no sooner gotten out of the Humber, but the wind began to blow, and the waves to rise in a most frightful manner; and as I had never been at sea before, I was most inexpressibly sick in body, and terrified in my mind. I began now seriously to reflect upon what I had done, and how justly I was overtaken by the judgment of Heaven for my wicked leaving my father’s house, and abandoning my duty; all the good counsel of my parents, my father’s tears and my mother’s entreaties, came now fresh into my mind, and my conscience, whichwasnotyetcometothepitchofhardnesswhichithasbeensince, reproachedmewith the contempt of advice and the breach of my duty to God and my father.

All this while the storm increased, and the sea, which I had never been upon before, went very high, though nothing like what I have seen many times since; no, nor like what I saw a few days after. But it was enough to affect me then, who was but a young sailor, and had neverknownanythingofthematter.Iexpectedeverywavewouldhaveswallowedusup,and that every time the ship fell down, as I thought, in the trough or hollow of the sea, we should never rise more; and in this agony of mind I made many vows of resolutions, that if it would please God here to spare my life this one voyage, if ever I got once my foot upon dry land again, I would go directly home to my father, and never set it into a ship again while I lived; that Iwould take his advice, and never run myself into such miseries as these any more. Now Isawplainlythegoodnessofhisobservationsaboutthemiddlestationoflife,howeasy,how comfortably he had lived all his days, and never had been exposed to tempests at sea, or troubles on shore; and I resolved that I would, like a true repenting prodigal, go home to my father.

Thesewiseandsoberthoughtscontinuedallthewhilethestormcontinued,andindeedsome timeafter;butthenextdaythewindwas abatedandtheseacalmer,and I begantobealittle inured to it. However, I was very grave for all that day, being also a little sea-sick still; but towards night the weather cleared up, the wind was quite over, and a charming fine evening followed; the sun went down perfectly clear, and rose so the next morning; and having little

4

ornowind,andasmooth sea,thesunshininguponit,thesightwas,asIthought,themost delightful that ever I saw.

I had slept well in the night, and was now no more sea-sick but very cheerful, looking with wonder upon the sea that was so wrought and terrible the day before, and could be so calm and so pleasant in so little time after. And now lest my good resolutions should continue, my companion, who had indeed enticed me away, comes to me: “Well, Bob,” says he, clapping me on the shoulder, “how do you do after it? I warrant you were frighted, wa’n’t you, last night, when it blew but a capful of wind?” “A capful, d’you call it?” said I; It was a terrible storm.”“Astorm,youfoolyou,”repliedhe;“doyoucallthatastorm?Why,itwasnothingat all; give us but a good ship and sea-room, and we think nothing of such a squall of wind as that; but you’re but a fresh-water sailor, Bob. Come, let us make a bowl of punch, and we’ll forget all that; d’ye see what charming weather ’tis now?” To make short this sad part of my story, we went the old way of all sailors; the punch was made, and I was made drunk with it, and in that one night’s wickedness I drowned all my repentance, all my reflections upon my past conduct, and all my resolutions for my future. In a word, as the sea was returned to its smoothness of surface and settled calmness by the abatement of that storm, so the hurry ofmy thoughts being over, my fears and apprehensions of being swallowed up by the sea being forgotten, and the current of my former desires returned, I entirely forgot the vows and promises that I made in my distress. I found indeed some intervals of reflection, and the serious thoughts did, as it were, endeavorto return again sometime; but Ishook them off, and roused myself from them as it were from a distemper, and applying myself to drink and company, soon mastered the return of those fits, for so I called them, and I had in five or six days got as complete a victory over conscience as any young fellow that resolved not to be troubled with it could desire. But I was to have another trial for it still; and Providence, as in such cases generally it does, resolved to leave me entirely without excuse. For if I would not take this for a deliverance, the next was to be such a one as the worst and most hardened wretch among us would confess both the danger and the mercy.

The sixth day of our being at sea we came into Yarmouth roads; the wind having been contrary andtheweathercalm,wemadebutlittlewaysincethestorm.Herewewereobliged to come to an anchor, and here we lay, the wind continuing contrary, viz., at southwest, for seven or eight days, during which time a great many ships from Newcastle came into the same roads, as the common harbor where the ships might wait for a wind for the river.

Wehadnot,however, ridheresolong,butshouldhavetidedituptheriver, butthatthewind blew too fresh; and after we had lain four or five days, blew very hard. However, the roads

.being reckoned as good as a harbor, the anchorage good, and our ground-tackle very strong, our men were unconcerned, and not in the least apprehensive of danger, but spent the time in rest and mirth, after the manner of the sea; but the eighth day in the morning the wind increased,andwehadall handsatworktostrikeourtopmasts,andmakeeverythingsnugand close,thattheshipmightrideaseasyaspossible. Bynoontheseawentveryhighindeed,and our ship rid forecastle in, shipped several seas, and we thought once or twice our anchor had come home; upon which our master ordered out the sheet anchor, so that we rode with two anchors ahead, and the cables veered out to the better end.

Bythistimeitblewaterriblestormindeed,andnowIbegantoseeterrorandamazementin the faces even of the seamen themselves. The master, though vigilant to the business of perserving the ship, yet as he went in and out of his cabin by me, I could hear him softly to himself say several times, “Lord be merciful to us, we shall be all lost, we shall be all undone”; and the like. During these first hurries I was stupid, lying still in my cabin, which was in the steerage, and cannot describe my temper; I could ill reassume the first penitence,

5

which I had so apparently trampled upon, and hardened myself against; I though the bitternessofdeathhadbeenpast,andthatthiswouldbenothingtoo,likethefirst.Butwhen the master himself came by me, as I said just now, and said we should be all lost, I was dreadfully frighted; Igot up out of my cabin, and looked out but such a dismal sight Inever saw: the sea went mountains high, and broke upon us every three or four minutes; when I could look about, I could see nothing but distress round us. Two ships that rid near us we found had cut theirmasts by theboard, being deep loaden; and ourmen cried out that aship which rid about’s mile ahead of us was foundered. Two more ships being driven from their anchors,wererunoutoftheroadstoseaatalladventures,andthatwithnot amaststanding. The light ships fared the best, as not so much laboring in the sea; but two or three of them drove, and came close by us, running away with only their sprit-sail out before the wind.

Towards evening the mate and boatswain begged the master of our ship to let them cut away the foremast, which he was very unwilling to. But the boatswain, protesting to him that if he did not the ship would founder, he consented; and when they had cut away the foremast, the mainmaststoodsoloose,andshooktheshipsomuch,theywereobligedto cutherawayalso, and make a clear deck.

Any one may judge what a condition I must be in all this, who was but a young sailor, and who had been in such a fright before at but a little. But if I can express at this distance the thoughts I had about me at that time, I was in tenfold more horror of mind upon account of my formerconvictions, and then having returned from them to theresolutions Ihad wickedly takenatfirst,than Iwas atdeathitself;andthese, addedtotheterrorofthestorm,putmeinto suchaconditionthat Icanbynowordsdescribeit.Buttheworstwasnotcomeyet;thestorm continued with such fury that the seamen themselves acknowledged they had never known a worse. We had a good ship, but she was deep loaden, and wallowed in the sea, that the seameneverynow andthencriedoutshe wouldfounder. Itwasmy advantageinonerespect, that I did not know what they meant by founder till I inquired. However, the storm was so violent that I saw what is not often seen, the master, the boatswain, and some others more sensible than the rest, at their prayers, and expecting every moment when the ship would go to the bottom. In the middle of the night, and under all the rest of our distresses, one of the men that had been down on purposeto see, cried out wehad sprung aleak; anothersaid there was four foot water in the hold. Then all hands were called to the pump. At that very wordmy heart, as I thought, died within me, and I fell backwards upon the side of my bed where I sat, into the cabin.

However, the men aroused me, and told me that I, that was able to do nothing before, was as well able to pump as another; at which I stirred up and went to the pump and worked very heartily. While this was doing, the master seeing some light colliers, who,notabletorideout thestorm,wereobligedtoslipandrunawaytosea,andwouldcome near us, ordered to fire a gun as a signal of distress. I, who knew nothing what that meant, was so surprised that Ithought the ship had broke, or some dreadful thing had happened. In a word, Iwas so surprised that I fell down in a swoon. As this was a time when everybody had his own life to think of, nobody minded me, or what was become of me; but another man stepped up to the pump, and thrusting me aside with his foot, let me lie, thinking I had been dead; and it was a great while before I came to myself.

We worked on, but the water increasing in the hold, it was apparent that the ship would founder, and though the storm began to abate a little, yet as it was not possible she could swim till we might run into a port, so the master continued firing guns for help; and a light ship,whohadriditoutjustaheadofus,ventured aboatouttohelpus. Itwaswiththeutmost hazard the boat came near us, but it was impossible for us to get on board, or for the boat to lie near the ship’s side, till at last the men rowing very heartily, and venturing their lives to save ours, our men cast them a rope over the stern with a buoy to it, and then veered it out a

6

great length, which they after great labor and hazard took hold of, and we hauled them close under our stern, and got all into their boat. It was to no purpose for them or us after we were in the boat to think of reaching to their own ship, so all agreed to let her drive, and only to pullherintowardsshoreasmuchaswecould,and ourmasterpromisedthemthatiftheboat was staved upon shore he would make it good to their master; so partly rowing and partly driving, our boat went away to the norward, sloping towards the shore almost as far as Winterton Ness.

We were not much more than a quarter of an hour out of our ship but we saw her sink, and then I understood for the first time what was meant by a ship foundering in the sea. I must acknowledgeIhadhardlyeyestolookupwhentheseamentoldmeshewassinking;forfrom that moment they rather put me into the boat than that Imight be said to go in; my heart was, as it were, dead within me, partly with fright, partly with horror of mind and the thoughts of what was yet before me.

While we were in this condition, the men yet laboring at the oar to bring the boat near the shore, we could see, when, our boat, mounting the waves, we were able to see the shore”

great many people running along the shore to assist us when we should come near. But we madebutslowwaytowardstheshore,norwereweabletoreachtheshore, tillbeingpastthe lighthouse at Winterton, the shore falls off to the westward towards Cromer, and so the land broke off a little the violence of the wind. Here we got in, and though not without much difficulty got all safe on shore, and walked afterwards on foot to Yarmouth, where, as unfortunate men, we were used with great humanity as well by the magistrates of the town, who assigned us good quarters, as by particular merchants and owners of ships, and had money given us sufficient to carry us either to London or back to Hull, as we thought fit.

Had I now had the sense to have gone back to Hull, and have gone home, I had been happy, andmyfather,anemblemofourblessedSaviour’sparable,hadevenkilledthefattedcalffor me;forhearingtheship IwentawayinwascastawayinYarmouthroad,itwasagreatwhile before he had any assurance that I was not drowned.

But my ill fate pushed me on now with an obstinacy that nothing could resist; and though I had several times loud calls from my reason and my more composed judgment to get home, yet I had no power to do it. I knew not what to call this, nor will I urge that it is a secret overrulingdecreethathurriesusontobetheinstrumentsofourowndestruction,eventhough it be before us, and that we rush upon it with our eyes open. Certainly nothing but some such decreed unavoidable misery attending, and which it was impossible for me to escape, could have pushed me forward against the calm reasonings and persuasions of my most retired thoughts, and against two such visible instructions as I had met with in my first attempt.

My comrade, who had helped to harden me before, and who was the master’s son, was now less forward than I. The first time he spoke to me after we were at Yarmouth, which was not till two or three days, for we were separated in the town to several quarters — I say, the first time he was me, it appeared his tone was altered, and looking very melancholy and shaking his head, asked me how I did, and telling his father who I was, and how I had came this voyageonlyforatrialinordertogofartherabroad,hisfatherturningtomewithaverygrave and concerned tone, “Young man,” says he, “you ought never to go to sea any more, you oughttotakethisforaplainandvisibletoken,thatyouarenottobeaseafaringman.”“Why, sir,” said I,

“will you go to sea no more?” “That is another case,” said he; “it is my calling, and therefore my duty; but as you made this voyage for a trial, you see what a task Heaven has given you of what you are to expect if you persist; perhaps this is all befallen us on your account, like Jonah in the ship of Tarshish. Pray,” continues he, “what are you? and on what account did you go to sea?” Upon that I told him some of my story, at the end of which he

7

burstoutwithastrangekindofpassion.“WhathadIdone,”sayshe,“thatsuchanunhappy wretch

should comeinto my ship?Iwould not set my foot in thesameship with theeagain forathousandpounds.” This,indeed,was,as Isaid,anexcursionofhisspirits,whichwere got agitated by the sense of his loss, and was farther than he could have authority to go.

However, he afterwards talked very gravely to me, exhorted me to go back to my father, and not tempt Providence to my ruin; told me I might see a visible hand of Heaven against me.

“And,youngman,”saidhe,“dependuponit,ifyoudonotgoback,whereveryougoyouwill meet with nothing but disasters and disappointments, till your father’s words are fulfilled upon you.”

We parted soon after; for I made him little answer, and I saw him no more; which way he went, I know not. As for me, having some money in my pocket, I travelled to London by land;andthere, aswellasontheroad,hadmanystruggleswithmyselfwhatcourseoflifeI should take, and whether I should go home or go to sea.

As to going home, shame opposed the best motions that offered to my thoughts; and it immediately occurred to me how Ishould be laughed at among the neighbors, and should be ashamedtosee,notmyfatherandmotheronlybuteveneverybodyelse;fromwhenceIhave since often observed how incongruous and irrational the common temper of mankind is, especiallyofyouth,tothereason whichoughttoguidetheminsuchcases, viz.,thattheyare not ashamed to sin, and yet are ashamed to repent; not ashamed of the action for which they ought justly to be esteemed fools, but are ashamed of the returning, which only can make them be esteemed wise men.

In this state of life, however, I remained some time, uncertain what measures to take, and what course of life to lead. An irresistible reluctance continued to going home; and as I stayedawhile,theremembranceofthedistressIhadbeeninworeoff,andasthatabated,the little motion I had in my desires to a return wore off with it, till at last I quite laid aside the thoughts of it, and looked out for a voyage.

8

2. SlaveryAndEscape

Thatevilinfluencewhichcarriedmefirstawayfrommyfather’shouse,thathurriedmeinto the wild and indigested notion of raising my fortune, and that impressed those conceits so forcibly upon me as to make me deaf to all good advice, and to the entreaties and even command of my father — I say, the same influence, whatever it was, presented the most unfortunateof all enterprises to my view; and Iwent on board avessel bound to thecoast of Africa, or as our sailors vulgarly call it, a voyage to Guinea.

It was my great misfortune that in all these adventures I did not ship myself as a sailor, whereby, though I might indeed have worked a little harder than ordinary, yet at the same time I had learned the duty and office of a foremast man, and in time might have qualified myselfforamateorlieutenant,ifnotforamaster. Butasitwasalwaysmyfatetochoosefor the worse, so I did here; for having money in my pocket, and good clothes upon my back, I would always go on board in the habit of a gentleman; and so I neither had any business in the ship, or learned to do any.

It was my lot first of all to fall into pretty good company in London, which does not always happen to such loose and misguided young fellows as I then was; the devil generally not omitting to lay some snare for them very early; but it was not so with me. I first fell acquainted with the master of a ship who had been on the coast of Guinea, and who, having had very good success there, was resolved to go again; and who, taking a fancy to my conversation, which was not at all disagreeable at that time, hearing me say I had a mind to seetheworld,toldmeif Iwouldgothevoyage withhimIshouldbeatnoexpense; Ishould behismessmateandhis companion;andifIcouldcarry anythingwithme,Ishouldhaveall the advantage of it that the trade would admit, and perhaps I might meet with some encouragement.

I embraced the offer; and, entering into a strict friendship with this captain, who was an honestandplain-dealingman,Iwentthevoyagewithhim,andcarriedasmalladventurewith me, which by the disinterested honesty of my friend the captain, I increased very considerably, for I carried about L40 in such toys and trifles as the captain directed me tobuy. This L40 I had mustered together by the assistance of some of my relations whom I corresponded with, and who, I believe, got my father, or at least my mother, to contribute so much as that to my first adventure.

This was the only voyage which I may say was successful in all my adventures, and which I owetotheintegrityand honestyofmyfriendthecaptain;underwhom alsoIgotacompetent knowledgeofthemathematicsandtherulesofnavigation,learnedhowtokeepanaccountof the ship’s course, to take an observation, and, in short, to understand some things that were needful to beunderstood by asailor. For, as hetook delight to introduceme, Itook delight to learn; and, in a word, this voyage made me both a sailor and a merchant; for I brought home five pounds nine ounces of gold dust for my adventure, which yielded me in London at my return almost L300, and this filled me with those aspiring thoughts which have since so completed my ruin.

YeteveninthisvoyageIhadmymisfortunestoo;particularly,thatIwascontinuallysick, being thrown into a violent calenture by the excessive heat of the climate; our principal trading being upon the coast, for the latitude of 15 degrees north even to the line itself.

9

I was not set up for a Guinea trader; and my friend, to my great misfortune, dying soon after his arrival, I resolved to go the same voyage again, and I embarked in the same vessel with one who was his mate in the former voyage, and had now got the command of the ship. This was the unhappiest voyage that ever man made; for though I did not carry quite L100 of my new-gained wealth, so that Ihad L200 left, and which Ilodged with my friend’s widow, who was very just to me, yet I fell into terrible misfortunes in this voyage; and from the first was this, viz., our ship making her course towards the Canary Islands, or rather between those islands and the African shore, was surprised in the gray of the morning by a Turkish rover of Sallee, who gave chase to us with all the sail she could make. We crowded also as much canvas as our yards would spread, or our masts carry, to have got clear; but finding the pirate gained upon us, and would certainly come up with us in a few hours, we prepared to fight,ourshiphavingtwelveguns,andtherogueeighteen.Aboutthreeintheafternoonhecameup with us, and bringing to, by mistake, just athwart our quarter, instead of athwart our stern, as he intended, we brought eight of our guns to bear on that side, and poured in a broadsideupon him, which made him sheer off again, after returning our fire and pouring in also his small-shot from near 200 men which he had on board. However, we had not a man touched, all our men keeping close. He prepared to attack us again, and we to defend ourselves; but layingusonboardthenexttimeuponourotherquarter,heenteredsixtymenuponourdecks, who immediately fell to cutting and hacking the decks and rigging. We plied them with small-shot, half-pikes, powder-chests, and such like, and cleared our deck of them twice.

However,tocutshortthismelancholypartofourstory,ourshipbeingdisabled,andthreeof our men killed and eight wounded, we were obliged to yield, and were carried all prisoners into Sallee, a port belonging to the Moors.

The usage I had there was not so dreadful as at first I had apprehended, nor was I carried up thecountrytotheemperor’scourt,astherestofourmenwere,butwaskeptbythecaptainof the rover as his proper prize, and made his slave, being young and nimble, and fit for his business. At this surprising change of my circumstances from a merchant to a miserable slave, I was perfectly overwhelmed; and now I looked back upon my father’s prophetic discoursetome,that Ishouldbemiserable,andhavenonetorelieveme, which Ithoughtwas now so effectually brought to pass, that it could not be worse; that now the hand of Heaven had overtaken me, and I was undone without redemption. But alas! this was but a taste of the misery I was to go through, as will appear in the sequel of this story.

As my new patron, or master, had taken me home to his house, so I was in hopes that he would take me with him when he went to sea again, believing that it would some time or other be his fate to be taken by a Spanish or Portugal man-of-war; and that then I should be setatliberty.Butthishopeofminewassoontakenaway;forwhenhewenttosea,heleftme on shore to look after his little garden, and do the common drudgery of slaves about his house; and when he came home again from his cruise, he ordered me to lie in the cabin to look after the ship.

Here I meditated nothing but my escape, and what method Imight take to effect it, but found no way that had the least probability in it. Nothing presented to make the supposition of it rational; for I had nobody to communicate it to that would embark with me, no fellow-slave, no Englishman, Irishman, or Scotsman there but myself; so that for two years, though Ioften pleasedmyselfwiththeimagination,yetIneverhadtheleastencouraging prospectofputting it in practice.

After about two years an odd circumstance presented itself, which put the old thought of makingsomeattemptformylibertyagaininmyhead.Mypatronlyingathomelongerthan usual without fitting out his ship, which, as I heard, was for want of money, he used

10

constantly, once or twice a week, sometimes oftener, if the weather was fair, to take the ship’s pinnace, and go out into the road a-fishing; and as he always took me and a young Maresco with him to row the boat, we made him very merry, and Iproved very dexterous in catchingfish;insomuch,thatsometimeshewouldsendmewithaMoor,oneofhiskinsmen, and the youth the Maresco, as they called him, to catch a dish of fish for him.

It happened one time that, going a-fishing in a stark calm morning, a fog rose so thick, that though we were not half a league from the shore we lost sight of it; and rowing we knew not whitherorwhichway,welabored allday,andall thenextnight,andwhen themorningcame found we were pulled off to sea instead of pulling in for the shore; and that we were at least twoleaguesfromtheshore.However,wegotwellinagain,thoughwithagreatdealoflabor, and some danger, for the wind began to blow pretty fresh in the morning; but particularly we were all very hungry.

But our patron, warned by this disaster, resolved to take more care of himself for the future; and having lying by him the longboat of our English ship which he had taken, he resolved he would not go a-fishing any more without a compass and some provision; so he ordered the carpenter of his ship, who was also an English slave, to build a little state-room, or cabin, in the middle of the longboat, like that of a barge, with a place to stand behind it to steer and haul homethemain-sheet, and room beforefor a hand ortwo to stand and work thesails. She sailed with what we call a shoulder-of-mutton sail; and the boom jabbed over the top of the cabin,whichlayverysnugandlow,andhadinit roomforhimtolie,withaslaveortwo, and a table to eat on, with some small lockers to put in some bottles of such liquor as he thought fit to drink; particularly his bread, rice, and coffee.

Wewentfrequentlyoutwiththisboata-fishing,andas Iwasmostdexteroustocatchfishfor him, he never went without me. It happened that he had appointed to go out in this boat, either for pleasure or for fish, with two or three Moors of some distinction in that place, and for whom he had provided extraordinarily; and had therefore sent on board the boat over night alargerstoreofprovisions than ordinary; and had ordered meto get ready threefuzees with powder and shot, which were on board his ship, for that they designed some sport of fowling as well as fishing.

I got all things ready as he had directed, and waited the next morning with the boat, washed clean, her ancient and pendants out, and everything to accommodate his guests; when by and by my patron came on board alone, and told me his guests had put off going, upon some business that fell out, and ordered me with the man and boy, as usual, to go out with the boat and catch them some fish, for that his friends were to sup at his house; and commanded that assoonas Ihadgotsomefish,Ishouldbringithometohishouse;allwhichIpreparedtodo.

This moment my former notions of deliverance darted into my thoughts, for now I found I was like to have a little ship at my command; and my master being gone, I prepared to furnishmyself,notforafishingbusiness,butforavoyage;though Iknewnot,neitherdid I so much as consider, whither I should steer; for anywhere, to get out of that place, was my way.

My first contrivance was to make a pretence to speak to this Moor, to get something for our subsistence on board; for I told him we must not presume to eat of our patron’s bread. He said that was true; so he brought a large basket of rusk or biscuit of their kind, and three jars with fresh water, into the boat. I knew where my patron’s case of bottles stood, which it was evidentbythemakeweretakenoutofsomeEnglishprize;and Iconveyed themintotheboat whiletheMoorwasonshore,asiftheyhadbeen therebeforeforourmaster. Iconveyed also a great lump of beeswax into the boat, which weighed above half a hundredweight, with a

11

parcel of twine or thread, a hatchet, a saw, and a hammer, all of which were great use to us afterwards, especially the wax to make candles. Another trick I tried upon him, which he innocentlycameintoalso.Hisnamewas Ishmael,whotheycallMuly,orMoely;soIcalled to him,

“Moely,” said I, “our patron’s guns are on board the boat; can you not get a little powder and shot? It may be we may kill some alcamies (a fowl like our curlews) for ourselves, for I know he keeps the gunner’s stores in the ship.” “Yes,” says he, “I’ll bring some”;andaccordinglyhebroughtagreatleatherpouchwhichheldaboutapoundanahalf of powder, or rather more; and another with shot, that had five or six pounds, with some bullets, and put all into the boat. At the same time Ihad found some powder of my master’s in the great cabin, with which I filled one of the large bottles in the case, which was almo st empty, pouring what was in it into another; and thus furnished with everything needful, we sailed out of the port to fish. The castle, which is at the entrance of the port, knew who we were, and took no notice of us; and we were not above a mile out of the port before we hauled in our sail, and set us down to fish. The wind blew from the NNE., which was contrary to my desire; for had it blown southerly I had been sure to have made the coast of Spain, and at least reached to the bay of Cadiz; but my resolutions were, blow which way it would, I would be gone from the horrid place where I was, and leave the rest to Fate.

After we had fished some time and catched nothing, for when I had fish on my hook I would notpullthemup,thathemightnotseethem,IsaidtotheMoor,“Thiswillnotdo;ourmaster will not be thus served; we must stand farther off.” He, thinking no harm, agreed, and being in the head of the boat set the sails; and as I had the helm I run the boat out near a league farther, and then brought her to as if I would fish; when giving the boy the helm, I stepped forward to where the Moor was, and making as if Istooped for something behind him, Itook him by surprise with my arm under his twist, and tossed him clear overboard into the sea. He rose immediately, for he swam like a cork, and called to me, begged to be taken in, told mehewouldgoalltheworldoverwithme.Heswamsostrongaftertheboat,thathewouldhave reachedmeveryquickly, therebeingbutlittlewind;uponwhich Isteppedintothecabin,and fetching oneofthefowling-pieces, Ipresented it at him, and told him Ihad donehim no hurt, and if he would be quiet I would do him none. “But, said I, “you swim well enough to reach to the shore, and the sea is calm; make the best of your way to shore, and I will do you no harm;butifyoucomeneartheboat I’llshootyouthroughthehead,for Iamresolvedtohave my liberty.” So he turned himself about, and swam for the shore, and Imake no doubt but he reached it with ease, for he was an excellent swimmer.

I could have been content to have taken this Moor with me, and have drowned the boy, but therewasnoventuringtotrusthim.WhenhewasgoneIturnedtotheboy,whomtheycalled Xury, and said to him, “Xury, if you will be faithful to me I’ll make you a great man; but if you will not stroke your face to be true to me,” this is, swear by Mahomet and his father’s beard, “I must throw you into the sea too.” The boy smiled in my face, and spoke so innocently, that I could not mistrust him, and swore to be faithful to me, and go all over the world with me.

WhileIwasinviewoftheMoorthatwasswimming,Istoodoutdirectlytoseawiththeboat, rather stretching to windward, that they might think me gone towards the straits’ mouth (as indeed any one that had been in their wits must have been supposed to do); for who would have supposed we were sailed on to the southward to the truly barbarian coast, where whole nations of negroes were sure to surround us with their canoes, and destroy us; where wecould ne’er once go on shore but we should be devoured by savage beasts, or more merciless savages of humankind?

12

But as soon as it grew dusk in the evening, Ichanged my course, and steered directly south and by east, bending my course a little toward the east, that I might keep in with the shore; andhavingafair,freshgaleofwind,and asmooth,quietsea, Imadesuch sailthatIbelieve by the next day at three o’clock in the afternoon, when I first made the land, I could not be less than 150 miles south of Sallee; quite beyond the Emperor of Morocco’s dominions, or indeed of any other king thereabouts, for we saw no people.

Yet such was the fright I had taken at the Moors, and the dreadful apprehensions I had of falling into their hands, that I would not stop, or go on shore, or come to an anchor, the wind continuing fair, till I had sailed in that manner five days; and then the wind shifting to the southward, I concluded also that if any of our vessels were in chase of me, they also would now give over; so I ventured to make to the coast, and came to an anchor in the mouth of a little river, I knew not what, or where; neither what latitude, what country, what nations, or what river. I neither saw, nor desired to see, any people; the principal thing I wanted was fresh water. We came into this creek in the evening, resolving to swim on shore as soon as it was dark, and discover the country; but as soon as it was quite dark we heard such dreadful noisesofthebarking,roaring,andhowlingofwildcreatures,ofweknewnotwhatkinds,that the poor boy was ready to die with fear, and begged me not to go on shore till day. “Well, Xury,” said I, “then I won’t; but it may be we may see men by day, who will be as bad to us as these lions.” “Then we give them the shoot gun,” says Xury, laughing; “make them run ’way.”

Such English Xury spoke by conversing among us slaves. However, Iwas glad to see the boy so cheerful, and I gave him a dram (out of our patron’s case of bottles) to cheer him up. After all, Xury’s advice was good, and Itook it; we dropped our little anchor and lay still all night. I say still, for we slept none; for in two or three hours we saw vast great creatures (we knew not what to call them) of many sorts come down to the sea-shore and run into the water, wallowing and washing themselves for the pleasure of cooling themselves; and they made such hideous howlings and yellings, that I never indeed heard the like.

Xury was dreadfully frightened, and indeed so was I too; but we were both more frighted when we heard one of these mighty creatures come swimming towards our boat; we couldnot see him, but we might hear him by his blowing to be a monstrous huge and furious beast.

Xury said it was a lion, and it might be so for aught I know; but poor Xury cried to me to weigh the anchor and row away. “No,” says I, “Xury; we can slip our cable with the buoy to it, and go off to sea; they cannot follow us far.” I had no sooner said so, but I perceived the creature(whateveritwas)withintwooars’length,whichsomethingsurprisedme;however,I immediately stepped to the cabin door, and taking up my gun, fired at him, upon which he immediately turned about and swam towards the shore again.

But is is impossibleto describethehorriblenoises, and hideous cries and howlings, that were raised, as well upon the edge of the shore as higher within the country, upon the noise or report of the gun, a thing I have some reason to believe those creatures had never heard before. This convinced me that there was no going on shore for us in the night upon that coast;andhowtoventureonshoreintheday was anotherquestiontoo;fortohavefalleninto the hands of any of the savages, had been as bad as to have fallen into the hands of lions and tigers; at least we were equally apprehensive of the danger of it.

Bethatasitwould,wewereobligedtogoonshoresomewhereorotherforwater,forwehad not a pint left in the boat; when or where to get to it, was the point. Xury said if I would let him go on shore with one the jars, he would find if there was any water, and bring some to me. I asked him why he should go? Why I should not go and he stay in the boat? The boy answered with so much affection, that made me love him ever after. Says he, “If wild mans come,theyeatme,yougoway.”“Well,Xury,”saidI,“wewillbothgo;andifthewildmans

13

come,wewillkillthem,theyshalleatneitherofus.”SoIgaveXuryapieceofruskbreadto eat, and a dram out of our patron’s case of bottles which I mentioned before; and we hauled in the boat as near the shore as we thought was proper, and so waded on shore, carrying nothing but our arms and two jars for water.

I did not care to go out of sight of the boat, fearing the coming of canoes with savages down the river; but the boy seeing a low place about a mile up the country, rambled to it; and byand by I saw him come running towards me. I thought he was pursued by some savage, or frighted with some wild beast, and I ran forward towards him to help him; but when I came nearer to him, I saw something hanging over his shoulders, which was a creature that he had shot,likeahare,butdifferentincolor,andlongerlegs.However,wewereverygladofit,and it was very good meat; but the great joy that poor Xury came with was to tell me he hadfound good water, and seen no wild mans.

Butwefoundafterwardsthatweneednottakesuchpainsforwater,foralittlehigherupthe creek where we were we found the water fresh when the tide was out, which flowed but a littleway up; so wefilled ourjars, and feasted on thehare wehad killed, and prepared to go on our way, having seen no footsteps of any human creatures in that part of the country.

As I had been one voyage to this coast before, I knew very well that the Islands of the Canaries, and the Cape de Verde Islands also, lay not far off from the coast. But as I had no instruments to take an observation to know what latitude we were in, and did not exactly know,oratleastremember,whatlatitudetheywerein,Iknewnotwhereto lookforthem,or when to stand off to sea towards them; otherwise I might now easily have found some of these islands. But my hope was, that if I stood along this coast till I came to that part where the English traded, I should find some of their vessels upon their usual design of trade, that would relieve and take us in.

By the best of my calculation, that place where I now was must be that country which, lying between the Emperor of Morocco’s dominions and the negroes, lies waste and uninhabited, except by wild beasts; the negroes having abandoned it and gone farther south for fear of the Moors, and the Moors not thinking it worth inhabiting, by reason of its barrenness; and indeedbothforsakingitbecauseoftheprodigiousnumberoftigers,lions,leopards,andother furious creatures which harbor there; so that the Moors use it for their hunting only, where they go like an army, two or three thousand men at a time; and indeed for near a hundred miles together upon this coast we saw nothing but a waste uninhabited country by day, and heard nothing but howlings and roarings of wild beasts by night.

OnceortwiceinthedaytimeIthought IsawthePicoofbeingthehightopoftheMountain Teneriffe in the Canaries, and had a great mind to venture out in hopes of reaching thither; but having tried twice, I was forced in again by contrary winds, the sea also going too high for my little vessel; so I resolved to pursue my first design, and keep along the shore.

Several times I was obliged to land for fresh water after we had left this place; and once in particular,beingearlyin themorning,wecametoananchorunderalittlepointoflandwhich wasprettyhigh;andthetidebeginningtoflow,welaystilltogofartherin. Xury,whoseeyes were more about them than it seems mine were, calls softly to me, and tells me that we had best go farther off the shore; “For,” says he, “look, yonder lies a dreadful monster on the side ofthathillockfastasleep.”Ilookedwherehepointed,andsawadreadful monsterindeed,for it was a terrible great lion that lay on the side of the shore, under the shade of a piece of the hillthathungasitwerealittleoverhim.“Xury,”says I,“youshallgoonshoreandkillhim.” Xury looked frighted, and said, “Me kill! he eat me at one mouth;” one mouthful he meant.

14

However, Isaid no more to the boy, but bade him lie still, and Itook our biggest gun, which wasalmostmusketbore,andloadeditwithagoodchargeofpowder,andwithtwoslugs,and laid it down; then I loaded another gun with two bullets; and the third (for we had three pieces) I loaded with five smaller bullets.

I took the best aim I could with the first piece to have him shot into the head, but he lay so with his leg raised alittleabovehis nose, that the slugs hit his leg about theknee, and broke thebone.Hestartedupgrowlingatfirst,butfindinghislegbroke,felldownagain,andthen got up upon three legs and gave the most hideous roar that ever I heard. I was a little surprised that I had not hit him on the head.

However, I took up the second piece immediately, and, though he began to move off, fired again,andshothimintothehead, andhadthepleasuretohimdrop,andmakebutlittlenoise, but lay struggling for life. Then Xury took heart, and would have me let him go on shore. “Well, go,” said I; so the boy jumped into the water, and taking a little gun in one hand,swam to shore with the other hand, and coming close to the creature, put the muzzle of the piece to his ear, and shot him into the head again, which despatched him quite.

Thiswasgameindeedto us,butthiswasnofood;and Iwasverysorrytolosethreecharges of powder and shot upon a creature that was good for nothing to us. However, Xury said he wouldhavesomeofhim; sohecomesonboard,andaskedmetogivehimthehatchet.“For what, Xury?” said I. “Me cut off his head,” said he. However, Xury could not cut off his head, but he cut off a foot, and brought it with him, and it was a monstrous great one.

Ibethoughtmyself,however,thatperhapstheskin ofhimmightonewayorotherbeofsome value to us; and I resolved to take off his skin if I could. So Xury and I went to work with him; but Xury was much the better workman at it, for I knew very ill how to do it. Indeed, it took us both the whole day, but at last we got off the hide of him, and spreading it on the top of our cabin, the sun effectually dried it in two days’ time, and it afterwards served me to lie upon.

15

3. WreckedOnADesertIsland

After this stop we made on to the southward continually for ten or twelve days, living very sparing on our provisions, which began to abate very much, and going no oftener into the shore than we were obliged to for fresh water. My design in this was to make the river Gambia or Senegal — that is to say, anywhere about the Cape de Verde — where I was in hopes to meet with some European ship; and if I did not, I knew not what course I had totake, but to seek out forthelands, orperish there among thenegroes. Iknewthat all theships from Europe, which sailed either to the coast of Guinea or to Brazil, or to the East Indies, madethiscape,orthoseislands;andinaword, Iputthewholeofmyfortuneuponthissingle point, either that I must meet with some ship, or must perish.

When I had pursued this resolution about ten days longer, as I have said, I began to see that thelandwasinhabited;andintwoorthreeplaces, aswesailedby,wesaw peoplestandupon the shore to look at us; we could also perceive they were quite black, and stark naked. I was once inclined to have gone on shore to them; but Xury was my better counsellor, and said to me.

“No go, no go.” However, I hauled in nearer the shore that I might talk to them, and I found they ran along the shore by me a good way. I observed they had no weapons in their hands, except one, who had a long slender stick, which Xury said was a lance, and that they would throw them a great way with good aim. So I kept a distance, but talked with them by signs as well as I could, and particularly made signs for something to eat; they beckoned to me to stop my boat, and that they would fetch me some meat. Upon this I lowered the top of my sail, and lay by, and two of them ran up into the country, and in less than half an hour came back, and brought with them two pieces of dried flesh and some corn, such as is the produce of their country; but we neither knew what the one or the other was. However, we were willing to accept it, but how to come at it was our next dispute, for I was not for venturing on shore to them, and they were as much afraid to us; but they took a safe way for usall,fortheybroughtittotheshoreandlaiditdown,andwentandstood agreatwayofftill we fetched it on board, and then came close to us again.

We made signs of thanks to them, for we had nothing to make them amends. But an opportunity offered that very instant to oblige them wonderfully; for while we were lying by the shore came two mighty creatures, one pursuing the other (as we took it) with great fury from themountains towards thesea; whetherit was themalepursuing thefemale, orwhether they were in sport or in rage, we could not tell, any more than we could tell whether it was usual or strange, but I believe it was the latter; because in the first place, those ravenous creatures seldom appear but in the night; and in the second place, we found the people terribly frightened, especially thewomen. Theman that had thelanceordart did not fly from them, but the rest did; however, as the two creatures ran directly into the water, they did not seem to offer to fall upon any of the negroes, but plunged themselves into the sea, and swam about, as if they had come for their diversion. At last, one of them began to come nearer our boatthanatfirst Iexpected;butIlay readyforhim,for Ihadloadedmygunwithallpossible expedition, and bade Xury load both the others. As soon as he came fairly within my reach, I fired, and shot him directly into the head; immediately he sunk down into the water, but rose instantly,andplungedupanddown,asifhewasstrugglingforlife,andso indeedhewas.He immediately made to the shore; but between the wound, which was his mortal hurt, and the strangling of the water, he died just before he reached the shore.

It is impossible to express the astonishment of these poor creatures, at the noise and the fire ofmygun;someofthemwereevenreadytodieforfear,andfelldownas deadwiththevery

16

terror. But when they saw the creature dead, and sunk in the water, and that I made signs to them to come to the shore, they took heart and came to the shore, and began to search for the creature. Ifound him by his blood staining thewater: and by thehelp of arope, which Islung roundhim,andgavethenegroestohaul,theydraggedhimontheshore,andfoundthatitwas a most curious leopard, spotted, and fine to an admirable degree; and the negroes held uptheir hands with admiration, to think what it was I had killed him with.

The other creature, frighted with the flash of fire and the noise of the gun, swam on shore, andrandirectlytothemountainsfromwhencetheycame;norcould I,atthatdistance,know what it was. I found quickly the negroes were for eating the flesh of this creature, so I was willing to have them take it as a favor from me; which, when I made signs to them that they might take him, they were very thankful for. Immediately they fell to work with him; and though they had no knife yet, with a sharpened piece of wood, they took off his skin as readily, and much more readily, than we could have done it with a knife. They offered me someoftheflesh,which Ideclined,makingasifIwouldgiveitthem,butmadesignsforthe skin, which they gave me very freely, and brought me a great deal more of their provision, which, though I did not understand, yet I accepted. Then I made signs to them for some water, and held out one of my jars to them, turning it bottom upward, to show that it was empty, and that I wanted to have it filled. The called immediately to some of their friends, and there came two women, and brought a great vessel made of earth, and burnt, as I suppose, in the sun; this they set down for me, as before, and I sent Xury on shore with my jars, and filled them all three. There women were as stark naked as the men.

I was now furnished with roots and corn, such as it was, and water; and leaving my friendly negroes, I made forward for about eleven days more, without offering to go near the shore,till I saw the land run out a great length into the sea, at about the distance of four or five leagues before me; and the sea being very calm, I kept a large offing, to make this point. At length, doubling the point, at about two leagues from the land, Isaw plainly land on the other side, to seaward; then I concluded, as it was most certain indeed, that this was the Cape de Verde, and those the islands, called from thence Cape de Verde Islands. However, they were atagreatdistance,and Icouldnotwelltellwhat Ihadbesttodo;forifIshouldbetakenwith a fresh of wind, I might neither reach one or other.

In this dilemma, as I was very pensive, I stepped into the cabin, and sat me down, Xury having the helm; when, on a sudden, the boy cried out, “Master, master, a ship with a sail!”

and the foolish boy was frighted out of his wits, thinking it must needs be some of his master’sshipssenttopursueus,when Iknewweweregotten farenoughoutoftheirreach. I jumped out ofthecabin, and immediately saw, not only theship, but what shewas, viz., that it was a Portuguese ship, and, as I thought, was bound to the coast of Guinea, for negroes.

But when I observed the course she steered, I was soon convinced they were bound some otherway,anddidnotdesigntocomeanynearertotheshore;uponwhich Istretchedoutto sea as much as I could, resolving to speak with them, if possible.

With all the sail I could make, I found I should not be able to come in their way, but they would be gone by before I could make any signal to them; but after I had crowded to the utmost, and began to despair, they, it seems, saw me by the help of their perspective glasses, and that it was some European boat, which, as they supposed, must belong to some ship that was lost, so they shortened sail to let me come up. I was encouraged with this; and as I had my patron’s ancient on board, I made a waft of it to them for a signal of distress, and fired a gun both of which they say; for they told me they saw the smoke, though they did not hearthegun.Uponthesesignalstheyverykindlybroughtto,andlaybyforme; andinaboutthree hours’ time I came up with them.

17

They asked me what I was, in Portuguese, and in Spanish, and in French, but I understood none of them; but at last a Scots sailor, who was on board, called to me, and I answered him, andtoldhimIwas anEnglishman,thatIhadmademyescapeoutofslaveryfromtheMoors, at Sallee.

Then they bade me come on board, and very kindly took me in, and all my goods.

It was an inexpressible joy to me, that any one will believe, that I was thus delivered, as I esteemed it, from such a miserable, and almost hopeless, condition as I was in; and I immediatelyofferedall Ihadtothecaptainofthe ship,asareturn formydeliverance.Buthe generouslytoldmehewouldtakenothingfromme,butthatallIhadshouldbedeliveredsafe to me when I came to the Brazils. “For,” says he, “I have saved your life on no other terms than I would be glad to be saved myself; and it may, one time or other, be my lot to be taken up in the same condition. Besides,” says he, “when I carry you to the Brazils, so great a way from your own country, if I should take from you what you have, you will be starved there, and then I only take away that life I have given. No, no, Seignior Inglese,” says he, “Mr.

Englishman,Iwillcarry youthitherincharity,andthosethingswillhelpyoutobuyyour subsistence there, and your passage home again.”

As he was charitable in his proposal, so he was just in the performance to a tittle; for he orderedtheseamenthatnoneshouldoffertotouchanythingIhad;thenhetookeverything into his own possession, and gave me back an exact inventory of them, that I might have them, even so much as my three earthen jars.

Astomyboat,itwasaverygoodone, andthathesaw,andtoldmehewouldbuyitofmefor the ship’s use, and asked me what I would have for it? I told him he had been so generous to me in everything, that I could not offer to make any price of the boat, but left it entirely to him; upon which he told me he would give me a note of his hand to pay me eighty pieces of eight for it at Brazil, and when it came there, if any one offered to give more, he would make it up.

He offered me also sixty pieces of eight for my boy Xury, which Iwas loth to take; not that I was not willing to let the captain have him, but I was very loth to sell the poor boy’s liberty, who had assisted me so faithfully in procuring my own. However, when I let him know my reason, he owned it to be just, and offered me this medium, that he would give the boy an obligation to set him free in ten years if he turned Christian. Upon this, and Xury saying he was willing to go to him, I let the captain have him.

Wehad averygoodvoyagetotheBrazils,andarrivedintheBaydeTodoslosSantos,orAll Saints’

Bay, in about twenty-one days after. And now I was once more delivered from the most miserable of all conditions of life; and what to do next with myself I was now to consider.

The generous treatment the captain gave me, I can never enough remember. He would take nothingofmeformypassage,gavemetwentyducatsfortheleopard’sskin,andfortyforthe lion’s skin, which I had in my boat, and caused everything I had in the ship to be punctually delivered me; and what Iwas willing to sell hebought, such as thecaseof bottles, two ofmy guns, and a piece of the lump of beeswax, — for I had made candles of the rest; in a word, I made about 220 pieces of eight of all my cargo, and with this stock I went on shore in the Brazils.

I had not been long here, but being recommended to the house of a good honest man like himself,whohadaningeinoastheycallit,thatis,aplantationandasugar-house, Ilivedwith him some time, and acquainted myself by that means with the manner of their planting and making of sugar; and seeing how well the planters lived, and how they grew rich suddenly, I resolved, if I could get license to settle there, I would turn planter among them, resolving in the meantime to find out some way to get my money which I had left in London remitted to

18

me.Tothispurpose,gettingakindofaletterofnaturalization, Ipurchased asmuchlandthat was uncured as my money would reach, and formed a plan for my plantation and settlement, and such a one as might be suitable to the stock which I proposed to myself to receive from England.

I had a neighbor, a Portuguese of Lisbon, but born of English parents, whose name was Wells, and in much such circumstances as I was. I call him my neighbor, because his plantationlaynexttomine,andwe wentonvery sociablytogether.Mystockwasbutlow,as well as his; and we rather planted for food than anything else, for about two years. However, webegantoincrease,andourlandbegantocomeintoorder;sothatthethirdyearweplanted some tobacco, and made each of us a large piece of ground ready for planting canes in the year to come. But we both wanted help; and now I found, more than before, I had donewrong in parting with my boy Xury.

Butalas!formetodowrongthatneverdidright wasnogreatwonder. Ihadnoremedybutto go on. I was gotten into an employment quite remote to my genius, and directly contrary to the life I delighted in, and for which I forsook my father’s house, and broke through all his good advice; nay, I was coming into the very middle station, or upper degree of low life, which my father advised me to before; and which if I resolved to go on with, I might as well have stayed at home, and never have fatigued myself in the world as I had done. And I used often to say to myself I could have done this as well in England among my friends, as have gone 5,000 miles off to do it among strangers and savages, in a wilderness, and at such a distance as never to hear from any part of the world that had the least knowledge of me.

In this manner I used to look upon my condition with the utmost regret. I had nobody to converse with, but now and then this neighbor; no work to be done, but by the labor of my hands;and Iusedtosay, Ilivedjustlikeaman castawayuponsomedesolateisland,thathad nobodytherebuthimself.Buthowjusthasitbeen!andhowshouldallmen reflect,thatwhen they compare their present conditions with others that are worse, Heaven may oblige them to make the exchange, and be convinced of their former felicity by their experience; — I say, how just has it been, that the truly solitary life I reflected on in an island of mere desolation should be my lot, who had so often unjustly compared it with the life which I then led, in which, had I continued, I had in all probability been exceeding prosperous and rich.

I was in some degree settled in my measures for carrying on the plantation before my kind friend, the captain of the ship that took me up at sea, went back; for the ship remained there in providing his loading, and preparing for his voyage, near three months; when telling him whatlittlestockIhadleftbehindmeinLondon,hegavemethisfriendlyandsincereadvice: “Seignior Inglese,” says he, for so he always called me, “if you will give me letters, and a procuration here in form to me, with orders to the person who has your money in London to send youreffects to Lisbon, to such persons as Ishall direct, and in such goods as areproper for this country, I will bring you the produce of them, God willing, at my return. But since human affairs are all subject to changes and disasters, I would have you give orders but for onehundredpoundssterling,which,yousay,ishalfyourstock,andletthe hazardberunfor the first; so that if it come safe, you may order the rest the same way; and if it miscarry, you may have the other half to have recourse to for your supply.”

Thiswassowholesomeadvice,andlookedsofriendly,thatIcouldnotbutbeconvincedit wasthebestcourseIcouldtake;soIaccordinglypreparedletterstothegentlewomanwith whom I left my money, and a procuration to the Portuguese captain, as he desired.

I wrote the English captain’s widow a full account of all my adventures; my slavery, escape, andhow Ihad metwiththePortugal captainatsea, thehumanityofhis behavior,andin what

19

condition I was now in, with all necessary directions for my supply. And when this honest captain came to Lisbon, he found means, by some of the English merchants there, to send over not the order only, but a full account of my story to a merchant at London, who represented it effectually to her; whereupon, she not only delivered the money, but out of her ownpocketsentthePortugalcaptainaveryhandsomepresentforhishumanityandcharityto me.

The merchant in London vesting this hundred pounds in English goods, such as the captain had writ for, sent them directly to him at Lisbon, and he brought them all safe to me to the Brazils;amongwhich,withoutmydirection(forIwastooyounginmybusinesstothinkof them), he had taken care to have all sorts of tools, iron-work, and utensils necessary for my plantation, and which were of great use to me.

When this cargo arrived, I thought my fortune made, for I was surprised with joy of it; and mygoodsteward,thecaptain,hadlaidoutthefivepounds,whichmyfriendhadsenthimfor a present for himself, to purchase and bring me over a servant under bond for six years’ service, and would not accept of any consideration, except a little tobacco, which I would have him accept, being of my own produce.

Neither was this all; but my goods being all English manufactures such as cloth, stuffs, baise, and things particularly valuable and desirable in the country, I found means to sell them to a verygreatadvantage;so thatImaysay Ihadmorethanfourtimesthevalueofmyfirstcargo, and was now infinitely beyond my poor neighbor, I mean in the advancement of my plantation; for the first thing I did, I bought me a negro slave, and a European servant also; I mean another besides that which the captain brought me from Lisbon.

Butasabusedprosperityisoftentimesmadetheverymeansofourgreatestadversity,sowas it with me. I went on the next year with great success in my plantation. I raised fifty great rolls of tobacco on my own ground, more than I had disposed of for necessaries among my neighbors; and these fifty rolls, being each of a hundredweight, were well cured, and laid by against the return of the fleet from Lisbon. And now, increasing in business and in wealth, myheadbegantobefullofprojectsandundertakingsbeyondmyreach,suchasare,indeed, often the ruin of the best heads in business.

Had I continued in the station I was now in, I had room for all the happy things to have yet befallenmeforwhichmyfathersoearnestlyrecommendedaquiet,retiredlife,andofwhich hehad so sensibly described themiddlestation oflifeto befull of. But otherthings attended me,and Iwasstilltobethewillfulagentofallmy ownmiseries;andparticularlytoincrease my fault and double the reflections upon myself, which in my future sorrows I should have leisure to make. All these miscarriages were procured by my apparent obstinate adhering to my foolish inclination of wandering abroad, and pursuing that inclination in contradiction to the clearest views of doing myself good in a fair and plain pursuit of those prospects, and those measures of life, which Nature and Providence concurred to present me with, and to make my duty.

As I had once done thus in my breaking away from my parents, so I could not be content now, but I must go and leave the happy view I had of being a rich and thriving man in my newplantation,onlytopursuearashandimmoderatedesireofrisingfasterthanthenatureof the thing admitted; and thus I cast myself down again into the deepest gulf of human misery that ever man fell into, or perhaps could be consistent with life and a state of health in the world.

To come, then, by the just degrees to the particulars of this part of my story. You may suppose,thathavingnowlivedalmostfouryearsintheBrazils,andbeginningtothriveand

20

prosperverywelluponmyplantation,Ihadnotonlylearnedthelanguage,buthadcontracted acquaintanceandfriendshipamongmyfellow-planters,aswellasamongthemerchantsatSt.

Salvador, which was our port, and that in my discourses among them I had frequently given them an account of my two voyages to the coast of Guinea, the manner of trading with the negroes there, and how easy it was to purchase upon the coast for trifles — such as beads, toys, knives, scissors, hatchets, bits of glass, and the like — not only gold-dust, Guinea grains, elephants’ teeth, etc. but negroes, for the service of the Brazils in great numbers.

Theylistenedalwaysveryattentivelytomydiscoursesontheseheads,butespeciallytothat part which related to the buying negroes; which was a trade, at that time, not only not far entered into, but, as far as it was, had been carried on by the assiento, or permission, of the KingsofSpainandPortugal,andengrossedinthepublic,sothatfewnegroeswerebrought, and those excessive dear.

It happened, being in company with some merchants and planters of my acquaintance, and talkingofthosethingsveryearnestly,threeofthemcametonethenextmorning,andtoldme theyhadbeenmusingverymuchuponwhat Ihad discoursedwiththemof, thelastnight,and they came to make a secret proposal to me. And after enjoining me secrecy, they told me that theyhadamindtofitoutashiptogotoGuinea;thattheyhadallplantationsaswellas I,and were straitened for nothing so much as servants; that as it was a trade that could not becarried on because they could not publicly sell the negroes when they came home, so they desired to make but one voyage, to bring the negroes on shore privately, and divide them among their own plantations; and, in a word, the question was, whether I would go their supercargo in the ship, to manage the trading part upon the coast of Guinea; and they offered me that I should have my equal share of the negroes without providing any part of the stock.

This was a fair proposal, it must be confessed, had it been made to any one that had not a settlement and plantation of his own to look after, which was in a fair way of coming to be very considerable, and with a good stock upon it. But for me, that was thus entered and established, and had nothing to do but go on as Ihad begun, forthreeorfouryears more, and to have sent for the other hundred pounds from England; and who, in that time, and with that littleaddition,couldscarcehavefailedofbeingworththreeorfourthousandpoundssterling, and that increasing too — for me to think of such a voyage, was the most preposterous thing that ever man, in such circumstances, could be guilty of.

But I, that was born to be my own destroyer, could no more resist the offer than I could restrain my first rambling designs, when my father’s good counsel was lost upon me. In a word, I told them I would go with all my heart, if they would undertake to look after my plantation in my absence, and would dispose of it to such as I should direct if I miscarried.

This they all engaged to do, and entered into writings or covenants to do so; and I made a formalwilldisposingofmyplantationandeffect, incaseofmydeath;makingthecaptainof the ship that had saved my life, as before, my universal heir, but obliging him to dispose of my effects as I had directed in my will; one-half of the produce being to himself, and the other to be shipped to England.

In short, Itook all possible caution to preserve my effects and keep up my plantation. Had I usedhalfasmuchprudencetohavelookedintomyowninterest,andhavemadeajudgment of what Iought to have done and not to have done, Ihad certainly never gone away from so prosperous an undertaking, leaving all the probably views of a thriving circumstance, and gone upon a voyage to sea, attended with all its common hazards, to say nothing of the reasons I had to expect particular misfortunes to myself.

21

ButIwashurriedon, and obeyedblindlythedictatesofmyfancyratherthanmyreason.And accordingly, the ship being fitted out, and the cargo furnished, and all things done as by agreement by my partners in the voyage, I went on board in an evil hour, the (first) of (September, 1659), being the same day eight year that I went from my father and mother at Hull, in order to act the rebel to their authority, and the fool to my own interest.

Our ship was about 120 tons burthen, carried six guns and fourteen men, besides the master, hisboy,andmyself.Wehadonboardnolargecargoofgoods,exceptofsuchtoysaswerefit for our trade with the negroes — such as beads, bits of glass, shells, and odd trifles,especially little looking-glasses, knives, scissors, hatchets, and the like.

The same day I went on board we set sail, standing away to the northward upon our own coast, with design to stretch over for the African coast, when they came about 10 or 12

degrees of northern latitude, which, it seems, was the manner of their course in those days.

We had very good weather, only excessive hot, all the way upon our own coast, till we came the height of Cape St. Augustino, from whence, keeping farther off at sea, we lost sight of land, and steered as if we was bound for the Isle Fernando de Noronha, holding our course NE. by N., and leaving those isles on the east. In this course we passed the line in about twelve days’ time, and were, by our last observation, in 7 degrees 22 minutes northern latitude, when a violent tornado, or hurricane, took us quite out of our knowledge. It began from the south-east, came about to the north-west, and then settled into the north-east, from whence it blew in such a terrible manner, that for twelve days together we could do nothing butdrive,and,scudding awaybeforeit,letitcarryuswhereverfateandthefuryofthewinds directed; and during these twelve days I need not say that I expected every day to be swallowed up, nor, indeed, did any in the ship expect to save their lives.

In this distress we had, besides the terror of the storm, one of our men died of the calenture, and one man and the boy washed overboard. About the twelfth day, the weather abating a little, the master made an observation as well as he could, and found that he was in about 11

degrees north latitude, but that he was 22 degrees of longitude difference west from Cape St.