10

Fairy-Tale Gods

THERE was once a man named Hellen—strange-sounding name for a man, isn’t it? He was not a Semite and not a Hamite. He was an Aryan. He had a great many children and children’s children, and they called themselves Hellenes. They lived in a little scrap of a country that juts out into the Mediterranean Sea, and they called their land Hellas. I once upset a bottle of ink on my desk, and the ink ran out into a wriggly spot that looked exactly as Hellas does on the map. Though Hellas is hardly any bigger than one of our States, its history is more famous than that of any other country of its size in the world. We call Hellas “Greece” and the people who lived there “Greeks.”

About the same time the Jews were leaving Egypt, about the time when people were beginning to use iron instead of bronze, that is, about 1300 B.C., we first begin to hear of Hellas and the Hellenes, of Greece and the Greeks.

The Greeks believed in many gods, not in one God as we do and as the Jews did, and their gods were more like people in fairy-tales than like divine beings. Many beautiful statues have been made of their different gods, and poems and stories have been written about them.

There were twelve—just a dozen—chief gods. They were supposed to live on Mount Olympus, which was the highest mountain in Greece. These gods were not always good, but often quarreled and cheated and did even worse things. The gods lived on a kind of food that was much more delicious than what we eat. It was called nectar and ambrosia, and the Greeks thought it made those who ate it immortal; that is, so that they would never die.

Let me introduce you to the family of the gods. I know you will be pleased to meet them. Most of them have two names.

Jupiter or Zeus is the father of the gods and the the king who rules over all human beings. He sits on a throne and holds a zigzag flash of lightning called a thunderbolt in his hand. An eagle, the king of birds, is usually by his side.

Juno or Hera is his wife and therefore queen. She carries a scepter, and her pet bird, the peacock, is often with her.

Neptune or Poseidon is one of the brothers of Jupiter. He rules over the sea. He rides in a chariot drawn by sea-horses and carries in his hand a trident, which looks like a pitchfork with three points. He can make a storm at sea or quiet the waves simply by striking them with his trident.

Vulcan or Hephæstus is the god of fire. He is a lame blacksmith and works at a forge. His forge is said to be in the cave of a mountain, and as smoke and fire come forth from some mountains they are called volcanoes after the god Vulcan inside.

Apollo is the most beautiful of all the gods. He is the god of the sun and of song and music. Every morning—so the Greeks said—he drives his sun-chariot across the sky from the east to the west, and this makes the sun-lighted day.

Diana or Artemis is the twin sister of Apollo. She is the goddess of the moon and of hunting.

Mars or Ares is the terrible god of war, who is only happy when a war is going on—so that he is happy most of the time.

Mercury or Hermes is the messenger of the gods. He has wings on his cap and on his sandals, and he carries in his hand a wonderful winged stick or wand, which, if placed between two people who are quarreling, will immediately make them friends. One day Mercury saw two snakes fighting and he put his wand between them, whereupon they twined around it as if in a loving hug, and ever since the snakes have remained entwined around it. This wand is called a caduceus.

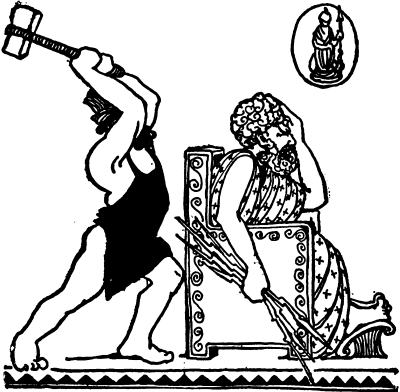

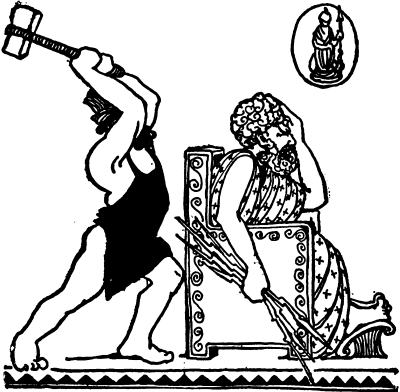

Birth of Minerva or Athene.

Minerva or Athene is the goddess of wisdom. She was born in a very strange way. One day Jupiter had a terrible headache—what we call a “splitting” headache. It got worse and worse, until at last he could stand it no longer, but he took a very strange way to cure it. He called Vulcan, the lame blacksmith, and told him to hit him on the head with his hammer. Though Vulcan must have thought this a funny request, of course he had to obey the father god. So he struck Jupiter a terrible blow on the head, whereupon there sprang forth Minerva in all her armor, and the headache, of which she had been the cause, had gone. So she was born from his brain, that is why she is the goddess of wisdom. Minerva’s Greek name is Athene, and she founded a great city in Greece and named it after herself, Athens. She is supposed to look out for this city as a mother does for her child.

Venus or Aphrodite is the goddess of love and beauty. She is the most beautiful of the goddesses as Apollo is the most beautiful of the gods. She is said to have been born from the sea-foam. Cupid, her son, is a little chubby boy with a quiver of arrows on his back. He goes about shooting his invisible arrows into the hearts of human beings, but instead of dying when they are hit they at once fall in love with some one. That is why we put hearts with arrows through them on valentines.

Vesta is the goddess of the home and fireside, who looks out for the family.

Ceres or Demeter is the goddess of the farmer. These are the twelve gods of the Olympian family.

Pluto is a brother of Jupiter. He rules the world underground and lives down there.

There are many other less important gods and goddesses as well as some gods that are half human, such as the three Fates and three Graces and the nine Muses.

Some of the planets in the sky which look like stars are still called by the names of these Greek gods. Jupiter is the name of the largest planet. Mars is the name of one that is reddish—the color of blood. Venus is the name of one that is very beautiful. There is also a Mercury and a Neptune.

It is hard for us to understand how the Greeks could have prayed to such gods as these, but they did. Their prayers, however, were not like ours. Instead of kneeling and closing their eyes as we do, they stood up and stretched their arms straight out before them. They did not pray to be forgiven for their sins and to be made better. They prayed for victory over their enemies or to be protected from harm.

When they prayed they often made the god an offering of animals, fruit, honey, or wine in order to please him so that he would grant their prayer. The wine they poured out on the ground, thinking the god would like to have them do this. The animals they killed and then burned by building a fire under them on an altar. This was called a sacrifice. Their idea seemed to be that even though the gods could not eat the meat of the animals nor drink the wine themselves, they liked to have something given up for them. And so even to-day we say a person makes a sacrifice when he gives up something for another.

When the Greeks were sacrificing they usually looked for some sign from the god to see whether he was pleased or not with the sacrifice and whether he would answer their prayer and do what they asked him or not. A flock of birds flying overhead, a flash of lightning, or any unusual happening they thought was a sign which meant something. Such signs were called “omens.” Some omens were good and showed that the god would do what he was asked, and some omens were bad and showed he would not. Omens were very much like some of the signs that people believe in even to-day when they say it is a good sign or good luck if you see the new moon over the right shoulder or a bad sign or bad luck if you spill the salt.

Not so very far from Athens is a mountain called Mount Parnassus. On the side of Mount Parnassus was a town called Delphi. In the town of Delphi there was a crack in the ground, from which gas came forth, somewhat as it does from cracks in a volcano. This gas was supposed to be the breath of the god Apollo, and there was a woman priest called a priestess who sat on a three-legged stool or tripod over the crack so as to breathe the gas. She would become delirious, as some people do when they are sick with fever and we say they are “out of their heads,” and when people asked her questions she would mutter strange things and a priest would tell what she meant. This place was called the Delphic Oracle, and people would go long distances to ask the oracle questions, for they thought Apollo was answering them.

The Greeks went to the oracle whenever they wanted to know what to do or what was going to happen, and they firmly believed in what the oracle told them. Usually, however, the answers of the oracle were like a riddle, so that they could be understood in more than one way. For instance, a king who was about to go to war with another king asked the oracle who would win. The oracle replied, “A great kingdom will fall.” What do you suppose the oracle meant? Such an answer, which you can understand in two or three ways, is still called “oracular.”