9

The Attic

Fine weather can't last forever. One morning, about a week later, Julian woke to a steady sound of rain.

"A good day to look for safes," he thought. He had spent the night at the Villa Caprice, as he would often do that summer. There were so many rooms in the house that there was also one for him.

"You must consider it your very own," his aunt had said, and this he was glad to do without a moment's hesitation.

It was a solemn, manly room with an enormous black bureau, an enormous black bed, an enormous black chair scratchily covered with horsehair. On the wall there was a steel engraving of the Roman Forum. Julian sat up and looked at his stately room. Othello, who had also spent the night, was lying on the oval rug before the fireplace. He suited the room admirably; he was a very solemn-looking dog, particularly when he was asleep.

Beyond the window the rain fell, straight down; all that could be seen through it was the deepened green of leaves.

Julian jumped out of bed and picked his clothes up from the floor; they had skidded off the horsehair chair, where he had tossed them the night before.

Othello woke up, too, and greeted him with a wide pink yawn.

"Maybe we'll find a fortune today," Julian told him.

His room also had a paneled wainscoting of dark wood. He had, of course, lost no time in tapping each panel, hoping to find one that sounded hollow, but none of them did, or at least not hollow enough. He tapped them again now, though, just to be on the safe side.

"Nope, no good. Come on, Thel; let's go."

Foster was sliding down the banisters slowly, because he didn't wish to bang into Miss McCurdy on the newel post. He had done this once, and Miss McCurdy's dancing foot, daintily raised, had met the back of his head with the force of a hammer; he could still feel the lump. But sliding down slowly was better than not sliding down at all.

"It's raining, it's pouring, the old man is snoring!" sang Foster lustily, as if this were an anthem of great wit and originality. When he dismounted at the end of the banister, he said: "Today I'm going to get into that suit of armor. I'm going to try to. Will you help me, Jule?"

"I might. After I've hunted for the safe."

But Portia was not interested in hunting for the safe. She was sure it would never be found, and anyway she wanted to explore the attic storeroom.

"All those trunks, Jule, all those boxes! Why, we might find anything. And it's just the day for it!"

"It's just the day to hunt for a safe."

"Why don't you compromise?" Mrs. Blake suggested. "Portia can explore the trunks while Julian searches the attic. My great-uncle Grover always kept his safe in the attic."

So after breakfast and their household chores were done, Portia and Julian repaired to the top of the house.

It was nice up there. It had a good dry attic smell, and there was coziness and comfort in the sound of rain on the roof. The storeroom seemed larger now; nearly all of the old furniture had been removed: some of it sold to meet expenses, some—most of it—moved downstairs to beautify the house. All that was left were some chairs without seats and a secretary that had lost its two left legs and leaned like the Tower of Pisa.

The trunks were grouped together in a surrounding of pitchers and basins and other oddments. The dressmaker's dummy stood sentry-duty at one side.

While Portia clattered and clanged, arranging a path amongst the crockery, Julian snooped about under the eaves, opening the doors of washstands. He had to help Portia open the first trunk, and when it was opened, it was a disappointment: nothing but old clothes and a strong smell of camphor. The clothes were petticoats mainly, dozens and dozens of massive petticoats, embroidered and ruffled and ribboned and ruched. There were many vast nightgowns, too, with real lace collars and real lace cuffs; there were pairs and pairs of stockings with embroidered clocks, and pairs and pairs of gloves with pearl buttons, folded in tissue paper. Altogether a very boring trunk, Portia thought. She put all the things back neatly, though. This had been a condition laid down firmly by her mother.

The next trunk was full of furs. Portia gave a faint shriek when she lifted the lid; the last thing she had expected was the sight of fur, and just for an instant she thought an animal was packed in there! It gave her a shock. This trunk released a blinding smell of moth balls and camphor, but the moths had obviously hardened themselves long ago to the defenses laid down against them; they had invaded the trunk as Caesar's legions had invaded Gaul. When Portia lifted out the thick soft cape that lay on top, she gave it a little shake, and all the fur departed from the skins; it rose in clouds of soft black thistledown, tickling her nose and getting in her eyelashes and nestling gently on her arms.

"Ow, Jule, help! Oh, how horrid! Ugh!" Portia blew fur from her lips, brushed herself off, shivered. "I bet this is exactly how Pandora felt!"

"Better keep on digging, then. Hope was in that box, remember? Maybe there's something great in this one, too."

"I'll never know," Portia said, shutting the clasps firmly, still shaking herself, and blowing at the little hairs of fur.

"Do you suppose Mrs. Brace-Gideon ever threw anything away?"

"I'm glad she didn't. I like finding things," Julian said. He was wearing a very old pith helmet that sat down on his ears like a soup tureen. Lacking panels to tap and quickly exhausting the safe-searching possibilities of the attic, he had been opening a box or two himself.

In the next trunk that Portia tackled there were many flannel bags with ribbon drawstrings, and each bag contained a pair of shoes or slippers: little pointy shoes with heels, buttoned ones, buckled ones, silk ones with bead-embroidered toes.

"Mrs. Brace-Gideon must have had very tiny feet for such a great big lady," Portia said thoughtfully, looking at the small frayed slipper in her hand.

"Jule?"

"M-m?... Yes?"

"Do you think it's really all right for us to do this? I mean, to go through all her very own things like this? I don't believe she'd like it if she knew ... do you?"

Julian considered.

"Well, think of it this way. Mrs. Brace-Gideon has been gone a long, long time. Long before our fathers and mothers were born, even. So now she's like someone in a book, or in history. If we were a couple of archaeologists digging up a buried palace that had belonged to an ancient queen or something, we wouldn't feel wrong about it, would we?"

"No, I suppose not."

"Well, there you are," Julian said handily, and Portia felt better.

Among the large trunks there was a very small one, a box really, covered with cowhide and bearing on its curved lid the initial D, made of brass nailheads. She lifted the lid cautiously (she had been very cautious since opening the fur trunk) and saw that the little chest was filled to the brim with yellowed paper bundles.

"Jule, come here; let's see what these are."

The paper was so old that it crumbled and powdered when she opened the first bundle; and what it had contained was a sea shell, curved and dappled as a little quail.

"Why, how pretty!"

"Look, it's got a label on it, too."

And so it had; a tiny glued-on label with the Latin name of the shell written on it in meticulous old-fashioned handwriting.

"Cypraea zebra," Julian read, pronouncing the zebra part correctly.

Portia had opened another bundle and held out a brown shell, fancy as a fern.

"Murex palmarosae," read Julian, stabbing wildly at pronunciation.

Then he undid a bundle himself.

"Anyway, I know what this one is," he said, showing her a large ear-shaped shell, lined with the luminous greens and blues of peacock feathers. "It's an abalone. But that's not what it says it is; it says it's a Haliotis something or other. I give up. I can't wait till I study Latin. How are you going to be a scientist without it?"

"I don't look forward to it in the least," said Portia. "And I'm never going to be a scientist."

Happy and absorbed, they sat cross-legged on the floor, taking out bundle after bundle. Outside of a museum they had never seen such shells: they were shaped like fans, lockets, towers, pin wheels, hearts, trumpets. They were pleated and patterned, tinted with pink, rose, crimson, yellow, mother-of-pearl; there were several pairs that looked as if they had petals and that were colored like dahlias.

"I'm going to take these down to show Mother, later," Portia said. "This is as good as a Christmas stocking, isn't it, Jule?"

"Better. More in it. I wonder who collected them all and marked them all?"

"There's an initial on the lid: the letter D."

"Oh. Then obviously it must have been that ancestor of Mrs. Brace-Gideon's: that Captain Deuteronomy Dadware. He must have sailed to every beach on earth!"

"The lucky!"

"I know," agreed Julian.

When they were done with the shells, they found some cardboard boxes containing quantities of old, old magazines: fashion magazines of the early 1900's adorned with many pictures of strangely shaped young ladies wearing hairdo's that jutted forward from their heads, and large upturned hats that shot forward from the hairdo's, so that each young lady looked something like a water pitcher.

Julian soon tired of these, but Portia was entranced. There were other sorts of magazines, too, even older: in one, Portia found a story called Peter Ibbetson. She liked the illustrations, and there were children in them, so she began to read....

When Foster started calling Julian at the top of his lungs, she hardly heard him, and when Julian told her he was going downstairs, she did not hear him, either. Sometimes a story can open a world for you: you step into it and forget the real one that you live in. Evidently this was such a story.

Foster was waiting on the downstairs landing by the suit of armor. He had a monkey wrench, a pair of pliers, and a can opener.

"I thought maybe you'd need these."

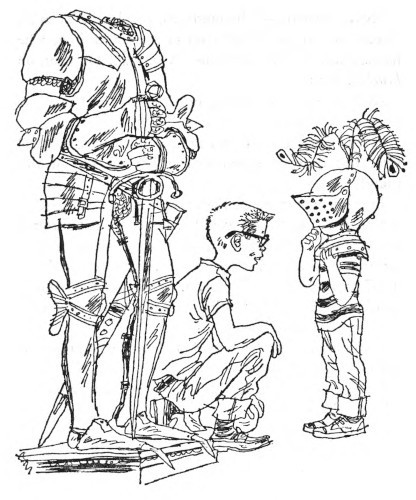

Julian looked at the suit of armor, then at Foster.

"Listen, Fang, it's still too big for you. No use even trying."

"I was afraid so. I suppose I'll just have to wait to grow into it, then, won't I?" said Foster philosophically.

"Perhaps we can try the helmet on you, though. If I can ever get it off; it probably hasn't been off in hundreds of years."

Julian gave a mighty tug, and the helmet flew up in his hands with no effort at all.

"Why, it's not even fastened down! O.K., Foss, stand still; let's try this bonnet on you."

Julian lowered the helmet gently down over Foster's head.

"There you go, Sir Launcelot! Can you see all right?"

"Yes, through the eye windows, but it isn't very comfortable in here," Foster complained. His voice inside the helmet had a clangorous twang: a robot's voice. "I don't like it very much. Something keeps tickling my nose. Ow."

"Wait a minute."

Julian lifted the sharp-snouted visor without any trouble. Foster's eyes and nose looked out, and a scrap of paper fluttered to the floor.

"Was that what was bothering my nose?"

But Julian didn't answer him. He had stooped to retrieve the piece of paper and was studying it.

"Now what the—" he muttered, perplexed. Then all at once he jumped straight up in the air as though he had stepped on a bee barefoot. "Oh, man! Oh man, oh brother! PORSH!"

And he went thundering up the stairs in a one-boy stampede to the attic.

"Hey, wait!" cried Foster in his robot voice: the steel visor had dropped down again. "Let me out of this thing!"

But Julian was gone. Foster sighed an echoing sigh within the helmet. He could see pretty well through the eye slits, but he felt top-heavy, as though he were wearing an iron bucket on his head, and he couldn't get it off by himself. Sighing again, he felt for the banister and started cautiously up the stairs to find his cousin.

"Portia!" roared Julian.

"Now what?" she said, marking her place on the page with her finger.

"Listen to this, just listen! This piece of paper fell out of the helmet—"

"What helmet?"

"Oh, never mind, it doesn't matter. Listen; here's what it says: zero dash, six R dash, two L dash, eight R dash, three whole turns R to eight."

Portia stared at him. "Are you crazy or something?"

"Doesn't it mean anything to you? Listen again. R means right and L means left, see? So it's zero dash, six right dash, two left dash, eight right dash, three whole turns right to eight. Do you dig it now?"

"No," Portia said.

"Oh, for Pete's sake. It's a combination, brain. It's sort of a recipe for opening a safe. Now do you see?"

"Mrs. Brace-Gideon's safe?"

Julian just sighed.

"Well, how do you know that's what it is? Maybe it's a recipe for some kind of dance: turn three times to the right and then six times to the left or whatever it is. It could be a dance."

Julian rolled his eyes upward.

"How do you start a dance at zero?" he inquired. "Just give me a clue."

At this moment, staring beyond him, Portia gasped. Footsteps were sounding slowly on the attic stairs, and just above the level of the attic floor appeared the helmet of an armored knight.

"Oh, Jule, oh, Jule," she whispered, grasping his arm; and then she wished she hadn't. How she wished she hadn't! Because below the shining headdress of Sir Launcelot was the figure of her brother Foster, sloppily attired in blue jeans and a grass-stained T-shirt.

"When Knighthood Was in Flower," commented Julian, kindly ignoring his cousin's moment of panic.

"Get me out of here, will you?" begged Foster, his plea reverberating in the helmet. "Please hurry up."

When Julian had liberated him, he did a little hopping.

"Now my head feels light again. I feel light all over, and nice. But you know what, Jule? I bet they used to have a lot of headaches in knight-days. And stiff necks, too. And if their ear itched, how could they ever scratch it?”