11

The Hot Spell

Early in July the weather turned very hot.

"Ain't had a spell like this in fourteen years," Eli Scaynes said happily, for though wiry, he was thin and elderly. The heat just suited his bones, and he went about his work humming a tuneless tune.

It suited the children, too, who wore as little as possible in the way of clothing and walked in and out of the hose sprinkler whenever they wanted to. It was hot in the morning when they woke up, and it kept on growing hotter all day long: still, burning, intense. The windless evenings, sparked with the drifting lights of fireflies and the fixed lights of stars, were so warm that the children were allowed to stay up later than usual. They made firefly lanterns and carried them off in the shadows, glimmering like will-o'-the-wisps, while the grownups sat in the lawn chairs talking and tinkling the ice in their cool glasses.

Each day it was hotter. Julian and Portia felt proud of it.

"The thermometer says 95°," Julian announced one morning; and on the next he said triumphantly, "It's 98!"

And then one day it was 100°, and the children were overjoyed, though the grownups were not.

The sun-beaten roses opened wide, large as lettuces, dropping their petals all too soon; and the soft new grass of the lawns felt warm and wilted under a bare foot.

The grownups sighed and complained; the dogs hung their tongues out; and the new kitten, Mousenick, slept flat as a dead kitten in any scrap of shade.

Mr. Ormond Horton had been as good as his word; he had brought Portia one of his cat's best kittens. He (it was a he-kitten) was little and gray, with tabby stripes on his sides like the wavery marks on watered silk, and eyes that were still blue because he was so young.

He did all the things a proper kitten should do. He romped, rolled, pursued his tail delightfully, tapped at a thimble with his perfect paw. He could flatten his ears, crouch, growl and stalk like a tiger. He could purr a miniature purr and wash his face better than Foster could. At dusk, small though he was, he could be quite alarming as he humped his back up, bushed his tail, and danced sideways staring eerily at something no one else could see.

Julian had named him, though Portia had planned to. He had just scooped the kitten up in his hand and said: "Here you go, Mousenick," and the name had stuck.

Everybody in the family liked him, and Gulliver and Othello did not mind him. As for Portia, whenever she looked at him, her heart melted.

During those hot days the Gone-Away houses stood cooking in the sun, giving off a smell of baked wood and dry rot, and very, very faintly of creosote: a delicious smell, the children thought. In the burning heat they were sometimes lured into the shady interiors of the most neglected houses, where, if they penetrated deeply enough, climbing over the rubble, the broken galleries and stairways, they could usually find a place, an inner hall or pantry, that was cool.

Judge Chater's was such a house; at the heart of the debris his dark-paneled dining room was like a cave: so damp that toadstools grew between the floor boards and the walls were stippled with mildew. Vandals had scratched their names on the plaster, broken the windowpanes and the Tiffany glass shades of the wall fixtures. Rainbow-colored shards glimmered among the toadstools.

"Yes. It's cool, but it's creepy," Portia said to Julian, who had led her there. "I don't—I'm not sure I like it."

"Well, it's not any place you'd want to stay," Julian admitted; and both of them thought of what Mrs. Cheever had told them.

"Next to Mrs. Brace-Gideon's house, the judge's house was the grandest one at Tarrigo," she had said. "Full of painted screens, you know, and jade figurines and porcelain vases, because he had spent many years in the Orient. He was a widower: a very rich elderly gentleman with no family left, except for his servants. They were all Chinese. I remember how they used to sound talking together: quacking and singing, or that's how it sounded to us. They were very nice and they liked children. It was so long ago that each of the menservants still wore a pigtail; and the women wore little coats and trousers, and when they ran, they trotted. All of them trotted on their boat-shaped slippers....

"Sometimes, I declare, even now when the wind's from the northeast, I fancy it carries a memory of their voices, a very faint quacking and singing!"

Standing in the cool ruin, Portia said to Julian: "I know I'd die if I should ever meet a ghost, but if I met a Chinese ghost, I'd die more!"

At that moment a swallow flew in through a window, swished like a scimitar past their faces, uttered its frightened chatter, and departed as Portia uttered a frightened squeak.

"Julian, come on; let's go!"

"Take it easy, now, ta-a-ke it easy," Julian drawled; but he was glad to go himself.

On the day the thermometer showed one hundred degrees, Portia and Julian set out early for Gone-Away. It was only a little after nine, but already every trace of dew was licked away. As usual they carried their lunch boxes, but for a change each was wearing a straw hat. The sun's rays could be brutal as the day neared noon.

They had to stop to watch a chipmunk in the woods; they had to stop while Julian caught a butterfly; when they heard a cuckoo's wooden-mallet note, they had to stop until Julian could spot him with the field glasses.

At Gone-Away, wading through yarrow and Queen Anne's lace, they made straight for Mr. Payton's house and found him working in his garden. He had a tropical, exotic look because he was wearing the pith helmet Julian had discovered in the attic. They had decided to give this to him when they noticed how often, on these hot days, he would remove his broad-brimmed hat, sighing as he blotted his forehead with one of his fine frayed handkerchiefs. The present had pleased him greatly.

"Always, since boyhood, I have longed to own a solar topee!" he exclaimed.

"That's another name for a pith helmet," Julian murmured to Portia, and Portia said she knew it.

Mr. Payton turned the helmet on his hand, admiring it. Then he clapped it on his head, slightly tilted, stroked his mustache preeningly, and went to look at his reflection in a windowpane.

"Now, all I need is a large umbrella with a green lining. And a camel," he had said. "Oh, and perhaps a pyramid or a sphinx. But seriously, Philosophers, this topee will be a boon: light and cool, yet no bee's sting can penetrate it when I tend the hives."

And after that whenever he did tend his beehives, whether the weather was warm or cold, he always wore the pith helmet under the bee veil instead of his usual hat.

Now he doffed it to them.

"Good morning, Philosophers. A pleasure to see you. We're in for another scorcher, I fear."

"The thermometer says 100° right now," Julian was glad to inform him. "Already. It will be worse than that by noon!" He sounded perfectly delighted, and was.

"By Jupiter!" Mr. Payton gave a whistle and dropped his hoe on the ground. "This is no day for gardening, then. Perhaps we'd better go and see how my sister is faring, though she never seems bothered by the heat."

They found Mrs. Cheever sitting on her front porch quite contented. Tarrigo lay at her feet, panting. He rolled his eyes at them pathetically, too hot to bark; but Mrs. Cheever looked cool and composed. She was wearing a dress of embroidered India mull. Once it had been white—"My sister Persy's graduation dress, just fancy!"—but time had tanned it and frayed it in many places. It looked very pretty, though, and she had pinned a rose to her collar, and the bow on her hair was the same color as the rose. She was sitting in a rocking chair with her mending, and on the table beside her lay a palm-leaf fan with green words painted on it: Atlantic City, 1889.

"Why, children, your clubhouse will be suffocating, won't it?"

"We're not going to use it today," Julian told her. "The guys—the other fellows—Tom Parks and Joe Felder are coming here to meet us—"

"And Lucy Lapham, too," Portia interrupted. "She's back visiting the Gaysons, thank goodness."

"The membership reunited, eh?" said Mr. Payton.

"Yes. They'll be here at eleven, and then we'll decide what to do. I wish there was anything to swim in but the brook."

"They won't let us use the river; too dangerous," Portia explained dolefully. "Oh, if only Tarrigo could turn back into a lake just for one day! I'm dying for a swim."

"Now, wait a moment, wait a moment," said Mr. Payton, frowning. "Let me see. There used to be—oh, years ago—but there used to be a limestone quarry back in the woods above Pork Ferry. Way back. Abandoned. Springs fed into it. Cold. Refreshing. Wonder if it's still there? Probably not. Probably a used-car lot by now, or a public dump, or a drive-in motion-picture theater, or some other confounded thing," he concluded grumpily; the heat had made him grumpy.

"But we could go and see, couldn't we, sir? If you gave us directions."

"Nonsense, I'll drive you there in the Machine. As far as I can; after that we'll walk."

"Now, Pin, I wonder if you should," his sister objected. "It might be too much for you. You might get heat exhaustion."

"Perfect nonsense, Minnie. You make me feel like an old crock!"

"Very well, then. Very well." Mrs. Cheever creaked her rocker back and forth. "How I wish you would not call me Minnie!"

Portia fanned herself with her hat. "We went exploring in Judge Chater's house yesterday, Aunt Minnehaha. I didn't like it very much. I thought it was spooky."

"I suppose it may be, now, all broken as it is. It was very grand once, though, wasn't it, Pin?... And every summer, just about this time of year, Judge Chater would give an evening party. He invited all the Tarrigo grownups and other ones from Pork Ferry and even Creston.

"Oh, we children hung out of our windows on that night! We could just glimpse the Chinese lanterns in the garden: big pearls, they looked like! And we could hear the carriages come driving up, so festive-sounding, and then the greetings and gabblings and the ladies laughing and trilling; and from the back of the house, where the kitchen was, came the sing-songing of the Chinese people. And the smell that wafted toward us! The party smell! Oh, Pin, do you remember?"

"Chinese delicacies. Fine cigars. Perfumery," Mr. Payton said with relish, stroking his mustache reminiscently.

"And there was a noise of popping, just like my little brother Lex's popgun, but it was really bottle corks. And then always at one point a silence would fall; an important chord would be struck on the piano, an introduction played, and then Mrs. Brace-Gideon's great big singing voice would come ballooning out of the windows into the night ... into the summer night ... and we children would hold our ears and roll up our eyes and groan out loud...."

"It was generally opined that Mrs. Brace-Gideon had her cap set for Judge Chater," Mr. Payton said.

"But she never got him. No, indeed she did not!" Mrs. Cheever shook her head decisively.

"The best thing, though," she continued, "the thing we were all waiting for, groggy with sleep though we were, was that very late in the evening—oh, very late indeed—a display of fireworks would be set off at the end of Judge Chater's dock."

"Set off by Wing Pin and Fat Lo, my two good friends," said Mr. Payton.

"And what fireworks they were! Weren't they, Pin? Oh, I never saw anything to equal them! Dragons! Fountains! Flower gardens! Big blazing birds! All made of fiery stars and colors! And everything sizzled and banged and dazzled, and there was a wonderful, exciting Chinese-y burning smell. Wasn't there, Pin?"

"M-m-m!" agreed her brother, smiling as he remembered. "Yes ... yes ... Wing Pin and Fat Lo. Years since I've thought of them. Fine fellows. One fat, one thin. (Fat Lo was the thin one.) They kept Tark and me and all the rest of the Tarrigo rascals supplied with Chinese firecrackers. Not just for the Fourth of July. No. All the time. Kept us very happy. Not the girls, though."

"Not the grownups, either," said his sister. "Poor Mrs. Ravenel—"

But Mrs. Cheever was interrupted here by the arrival of the other charter members of the Philosophers' Club: plump Tom Parks, handsome Joe Felder, and Portia's special friend Lucy Lapham, a dark-eyed girl with curly hair.

"Oh, I'm so glad to see you!" cried Portia, giving her a hug. "I'm so glad to see another girl!"

After the flurry of greetings, Tom Parks sat down on the porch steps with a heavy groan.

"I bet I've melted off five pounds."

"Better melt off twenty more," Julian advised him kindly.

They all looked very hot from their long walk. Their cheeks were strawberry red, their noses spangled with sweat, and their hair was soaking.

"I bet you could fry an egg on my hat," Joe Felder said. "I mean it's hot, man, hot!"

"Well, cheer up, though." Portia comforted them. "Uncle Pin is going to show us a place to swim."

"If it's still there," the old gentleman amended.

"Oh, boy, I hope it is!" Tom said fervently. Then his face fell. "We didn't bring any bathing suits. Heck!"

But Mrs. Cheever, it seemed, was equal to any occasion. She recalled that in one of the trunks that had been brought from the Big House, she had seen a quantity of ancient bathing suits, all sizes, that had long ago been worn by the Payton children.

"As Portia says, we were a very 'keeping' family. Thank fortune," Mrs. Cheever observed. "Girls, come with me to my storeroom, will you?"

And soon their arms were laden with the old wool bathing suits, smelling of moth balls so strongly that, as Lucy said, "You could lean against it."

"I advise you each to wear a boy's suit," Mrs. Cheever told them. "Good gracious, when I think of what we had to wear! Dresses with skirts and collars and sleeves! Stockings and sand shoes! Hats, straw hats, tied under our chins! I wonder they didn't make us wear gloves!"

Each boy's suit consisted of a striped tunic and striped trousers.

"It was the fashion then," said Mrs. Cheever. "Stripes were considered very continental."

Packed into the Franklin, Mr. Payton and the children steamed along the road to the hot highway, contributing an unusual odor of moth balls to the day. The highway danced with heat and shimmered with puddle mirages; and once Mr. Payton stopped the car so that they could watch the phenomenon of a turtle hurrying, trotting, across the blazing asphalt that burned its feet.

"I never saw a turtle run before. I never knew they could," Julian said in awe.

"They keep their secret well," Mr. Payton agreed. "It occurs to me that that old fable of the tortoise and the hare may well be simply propaganda put out by the hare."

They drove through the red-hot main street of Pork Ferry, where people carrying bags of groceries stopped to gape at the loud majestic progress of the Franklin. Mr. Payton bowed cordially to left and right, like visiting royalty.

After they left the village and the highway, they drove along a wooded road, slowly ascending. The Franklin huffed and struggled, and all of them, except Mr. Payton, got out and walked to make things easier for it.

"Just about here, I'd say," Mr. Payton announced finally, applying the brake. "There seems to be the remnant of a footpath."

It was a remnant indeed, and they kept losing it. The woods were shady, it was true, but the shade was hot and close; cat-claw scratched at them, and gnats kept trying to get into their eyes.

Mr. Payton, in the lead, fought his way through hazel bushes.

"It's clearing ahead," he called encouragingly, and in a moment they heard him give an exclamation of pleasure.

"Well, by Jove. Just look at that! A sight for sore eyes, Philosophers, and the same, exactly the same, as it was more than sixty years ago!"

The quarry held deep water in its cup: a little lake that lay still as a jewel, clear as a jewel, without a breath of air to wrinkle its surface. On this scorching noonday it was indeed a sight for sore eyes.

"Suave," breathed Julian.

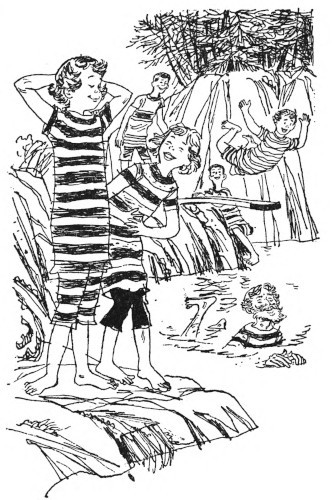

"What are we waiting for!" demanded Tom, pulling off his shirt. He and the other boys scrambled into the bushes to put on their suits, and Lucy and Portia found their own little dressing room behind a rock. Soon they were in the striped bathing suits. Lucy giggled at the sight of Portia, and Portia giggled at the sight of Lucy. The tight-fitting trousers reached well below their knees; the tight-fitting tunics hugged their ribs and had high necks and little shoulder sleeves. Lucy's stripes were black and yellow.

"You look like a big fat hornet," Portia said. Her stripes were red, white, and blue.

"You look like a skinny little patriotic barber pole," Lucy retorted.

The boys looked just as odd as they did, and so did Mr. Payton, whose suit, also vividly striped, was a relic of the same era.

Good-natured jeers and insults filled the air. So did an alien smell of moth balls. But not for long. Soon the children were popping into the water, happy as frogs.

It was cold! Cold and delicious, and so clear that they could see the carpet of drowned leaves lying far below them on the bottom.

At first they just swam and soaked and luxuriated. The midday sun blazed down on them. Mr. Payton swam the breast stroke holding his beard well out of the water and smiling benignly.

"Ah, by Jupiter, ah, by Jove," he purred contentedly.

"Let's stay here all day long, Uncle Pin, can we? Let's stay until it's suppertime."

"Why not, why not? When we're chilled, we'll lie on the rocks and bake ourselves dry, and then we'll swim again."

After a while Julian, who wanted to show off his diving, managed to find a plank and some boulders, and contrived a springboard. For the first few dives his skill was greatly admired, but then everybody else wanted a turn, even Tom Parks, who slapped the water resoundingly with his stomach every time.

The rock walls of the quarry echoed with squabbles and laughter and splashing and shouts. It echoed often with the words: "Look at me! Watch this! Hey, you guys, watch me!"

Old Mathew Partridgeberry, a recluse who lived in a house halfway up the mountain, heard the racket and came to see who was making it. Peeping between hazel leaves, he saw the children in their hornet stripes, and the old man in his. Not since his own distant childhood had he seen bathing suits like these! It gave him a turn. For a moment he felt a chill of superstition: could it be ... ghosts? A switch in time?... But then he smiled to himself. No. These were real live children; live, loud twentieth century children. A prank of some sort, or a game, no doubt. Still smiling, he turned away and was lost in the shrubbery, and no one ever knew that he had been there.