13

The Night of the Full Moon

Julian thought that the Blakes' house would never quiet down that night. He waited in his room, and waited. He felt himself getting sleepy and fought himself awake again. But finally, after all the last good nights were said, after all the tooth-brushings and murmurings and yawns and the closing of doors, he was able to creep out of his room and inch his way along the hall. Pressed against his chest, he held the bag of salami and dill pickles as if to keep them quiet, too.

Going down the front stairs, he forgot about the chirping stair tread, and of course it chirped loudly. Julian froze against the banister, staring down at Miss McCurdy's dim figure on the newel post. He had chosen to come this way because the back stairs were uncarpeted and noisy, and now—But no one came; nothing happened. Soon he continued down and tiptoed through the dark, watchful house to the back door. Behind him, the kitchen clock ticked in a little scolding voice.

Outdoors the sound of crickets shimmered in the air; everywhere, all over the summer land. The bright moon was small in the sky; it lighted up the edges of the clouds that were swimming toward it. A small soft wind moved forward, and the trees, dry with August, rustled their leaves and whispered.

Julian hurried along the drive. Moon patches dappled the ground, moving now as wind stirred the branches above. The honeysuckle trees were frightening at night; they looked like stooping figures: old soldiers, giants, in great dragging cloaks. Julian would not have admitted to a soul that his heart was hurrying in his chest, but it was. He was glad of the strong reassuring smell of the salami pressed against his ribs.

He slowed down when he came to the clearing, and his heart slowed down, too. The clearing was blue with moonlight and humming with crickets. The wind was warm. Far to the right there was a lighted window in Mr. Payton's house. Far to the left there was another in Mrs. Cheever's. Julian whistled a tune softly. He felt fine; everything was going right, and there, sure enough, waiting under the willow, was good old Tom Parks.

"Hey, where've you been! You're late!"

"Couldn't help it; they just wouldn't settle down and I had to wait. Where's Joe?"

"Search me. I waited for him, too, but his house was all dark, and when I threw pebbles at his window, they made such a racket, I was scared his folks would wake up, so I scrammed out of there pretty fast."

"Well, there's no sense waiting any longer. Let's go in. I don't think he chickened out, do you?"

"No, not Joe. He's no coward."

They entered the gaunt old house on tiptoe. It was still in there, and stale. It smelled of age, of decay, of damp; and it was very dark. The swimming clouds had caught the moon and covered it. Wind was beginning to tease the house.

"Ow!" exclaimed Tom in an outraged whisper; he had barked his shin on something. "I think it was a crazy idea not to bring a flashlight. I think it was dumb. Ow!"

The stairway quivered and swung as the boys felt their way up, and then felt their way to the room they had chosen. The moon tore itself free from clouds just long enough to light them in; then it was seized and darkened again. Far, far away there was a sort of shuddering. One could hardly have called it a sound.

"Was that thunder?" Tom asked apprehensively.

"I don't think so," Julian said. He certainly hoped not. He walked over to one of the windows and leaned his arms on the sill. Mrs. Cheever's house was dark now; all the world was dimmed, but you could tell there was a moon somewhere; the clouds could not quite smother its light. Below, the Vogelhart willow tossed softly in the wind.

"What do you say we have a snack?" Tom suggested.

That seemed a good idea to both of them, and they spread the blankets out on the floor and sat down. Tom rattled open the metal box. Julian crackled open the paper bag. Soon the air was warmed with an odor of peanuts and salami and dill pickle, and there was a sound of crunching. In the darkness everything tasted perfectly delicious.

"But salty," Julian objected. "Do you realize, Tom, that every single thing we brought is salty? Except the chocolate, and that always make you thirsty anyway."

"Well, we counted on Joe and the root-beer. How could we know? I'm not thirsty yet, though, are you? If we don't think about it, maybe we won't be."

"Maybe not." Julian agreed doubtfully. But the more he tried not to think about it, the more he thought about it. He could feel himself inventing his own thirstiness.

"Doggone it, what do you suppose happened to Joe?"

"I don't know. Fell asleep maybe, but there's no use worrying," Tom said philosophically. He was clanging things back into the tin box. "There's plenty left over for a snack later on if we need it."

He yawned a loud, satisfied yawn.

"Maybe we should sleep for a while."

"All right," Julian said, thinking about thirstiness; and they each stretched out on a blanket—it was much too warm for covers—and were quiet for nearly two minutes.

"Ow," Tom complained. "I never knew my bones had so many corners."

"You think you have troubles. You've got good natural padding, and I haven't. This is the hardest floor I ever felt."

"Well, we'll just have to get used to it. Soldiers do. Marines do."

"Rugs do," added Julian. "I don't mind the hardness of the floor so much, but I'm getting so thirsty I may have to drink the A.P. Decoction!"

Tom laughed. "Good thing you brought it anyway; here come the mosquitoes."

It was true. Somewhere just above their heads there was a sound like the wailing of the tiniest violin imaginable. Then another.

Hurriedly, Julian slapped his face and arms with Mrs. Cheever's famous Anti-Pest Decoction and handed the bottle to Tom. The room was suddenly permeated with an extraordinary smell, and because of it the sound of little violins diminished and was gone.

There was another distant shuddering in the air.

"It is thunder, Jule," Tom said accusingly. "I told you it was."

"It may never get here, though. It's a long way away."

"It will get here," Tom pronounced gloomily. "Just wait and see."

Outside, the wind was picking up; the trees churned under it, and all the reeds of Gone-Away hissed and rustled as they bowed.

"Sh-h! What's that!" whispered Tom, clutching Julian's arm.

"Hey, quit grabbing me like that; it startles me. What's what?"

"Listen—"

Clap came the sound; then a sort of jiggle and squeak; then clap again.

"Oh, that. It's only a broken shutter banging against the house. I think."

"You hope."

Both boys were whispering now, and Julian was wishing that they had chosen a room with a door that would close and preferably lock. This door had been wedged and warped ajar by time and weather. Nothing would ever close it now.

An abandoned house takes the wind the way a ship takes heavy seas. It creaks throughout, seems to stretch and groan, then settle for a bit, then stretch and groan again. It does other things, too, or at least this one did: it had a constantly varying repertory of creaks, tap-taps, and sounds like the most hesitant of footsteps.

When Julian had thought about this adventure, he had imagined that the scary thing would be the deadly silence of Judge Chater's midnight house. But now it was the sounds—all these different sounds—that were scaring him, and in his heart of hearts he was beginning to wish that he had never insisted on this idiotic undertaking: this "test!" The only good thing about it, at the moment, was that he felt too worried to be thirsty.

Evidently Tom shared his attitude about the venture. "I don't know," he said. "I don't see what good it's going to do our characters just to sit here in a thunderstorm in a beat-up old house, feeling scared. I think it's going to be bad for our characters. It is for mine."

"Well, why don't you go on home, then? Go ahead."

"And leave you here alone? You know I wouldn't. And anyhow, I'd probably get struck by lightning on my bike."

As if its name had been a cue, a tongue of lightning flickered, bright and close. It lighted the room so that for a split second each boy saw the worried solemn look on the face of the other. Then it was dark again, and approaching thunder slammed in the sky.

The broken shutter banged frantically; the old house strained and shook as if it were trying to tear itself loose from its foundations; and after a while the rain began all at once so that it fell on the roof like a solid thing.

The storm went on and on; they could not guess how long, but they knew when it had reached its pitch. The lightning, blue and blinding, winked and winked and hardly stopped winking; it seemed to lick the house. And the thunder hardly stopped thundering; sometimes it rolled and grumbled, and sometimes it burst the air with a bang; but it, like the lightning, seemed to have singled out this house for its prey.

"Hey, Jule! Listen!" shouted Tom. He had to shout above the uproar. "Anyone could be coming into this house, anything could be, and we'd never even hear it!"

But he was wrong. In one of those instants of lull, when the rain left to itself sounds peaceful and industrious, they heard something else—another sound—and it was in the house with them, yes, in this very house: hard, brisk footsteps, then an old voice calling....

"Uncle Pin?" breathed Tom, moving closer to Julian.

"Oh no, it's not him," whispered Julian, icy with the thought of Chinese ghosts.

"Listen—listen! Something is coming up the stairs!"

Something was. Something was coming, clicking and clattering—what? Oh, what? And then the sound was lost as the thunder burst itself apart, and burst the lightning with it. The world seemed to blow up.

Almost immediately there was a hideous tearing noise; a mighty crash inside the house!

And something white flashed by the door....

All this took only an instant, but when there is terror, an instant seems pinned motionless on time. The boys were clinging to each other, unashamed.

"The house has been struck," croaked Tom. "There'll be a fire."

"But the white thing! The white thing...."

There was another lull; in that last burst the storm seemed to have spent itself. Only the rain poured down and down; and now, quite close to them, the thin old voice called out again.

"Ma-a-a-a," it called.

Julian let go of Tom.

"It's only Uncle Sam! That crazy goat! He must have broken out of his pen."

"And come in here for shelter, I guess."

"Why here, I wonder? Why not somewhere else?"

But they would never know the reason. When they called him, Uncle Sam came clicking into the room, smelling strongly of wet goat, and the boys were so relieved, so glad to see him, that they gave him a chocolate bar to eat, paper and all.

"That crash though, brother, what was that?" Tom wondered, and sneezed. The air seemed suddenly thick and itchy. "Do you think we were struck?"

"No," said Julian, ashamed that his teeth were chattering still. "I think—I think that Uncle Sam finished off the s-stairs."

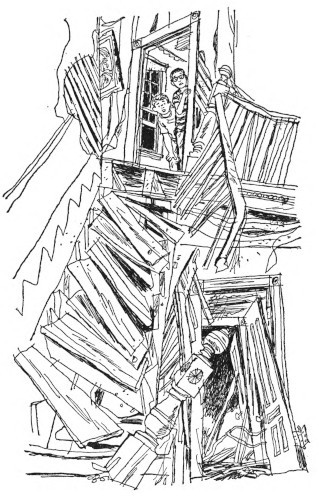

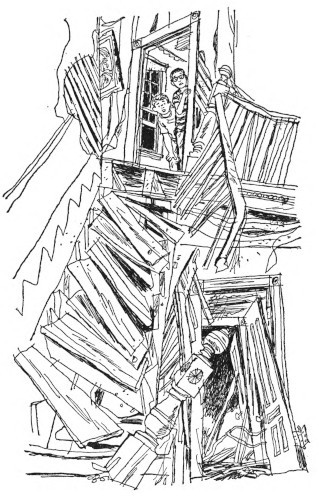

And that is what had happened, as they saw when they went to investigate. They could see, by the diminishing, fitful lightning, that where the stairs had been there was a chasm, edged with a hanging fringe of balustrade. The stifling cloud of dust and wood particles was beginning to settle now, but the boys kept sneezing.

"How'll we ever get down from here, I wonder?" said Tom.

"There are back stairs. Bound to be," Julian assured him.

"We'll have to wait till daylight to find them. We'd never do it in the dark; the floor back there is full of holes. I'm sorry, Jule, but I certainly think it was a crazy idea not to bring a flashlight. I certainly think it was dumb."

"So I agree with you now," Julian admitted handsomely. "It was idiotic and it was stupid and it was asinine. There. That satisfy you?"

"Sure. I guess so. Anyway, we've still got something to eat. That's one good thing."

They had another snack in the pitch dark, and Uncle Sam was glad to share it with them, but it caused Julian to remember about being thirsty.

The thunder had rolled itself away; the lightning was gone; but luckily the rain was heavy. It poured in a stream from the broken gutter above the window.

"Hold me by the belt, Tom, will you, and don't let me fall out? If I don't get a drink, I'll die."

So Tom gripped the back of Julian's belt, and Julian, by leaning far out of the window and practically dislocating his neck, was able to get his mouth into position under the spout and gulp down rainwater. It tasted of rust and wood and creosote and dead leaves and sparrows, but the main thing was that it was wet.

After he had drunk all he could, he held onto Tom's belt and performed the same service for him. Then they ate the last of the peanuts to take the taste of the rainwater out of their mouths, and after that they rolled themselves up in their blankets—it was cooler now—and lay down in the darkness.

"I'll never forget this night, man," Tom said. "Wait till we tell the kids: a real live ghost story."

"A real live goat story, you mean, and Uncle Sam's not the only goat," said Julian with a weary yawn. "I don't think anything makes you so tired as being good and scared and then getting over it."

Soon, in spite of their hard bed, they were sound asleep. The rain poured steadily all night. Uncle Sam settled down beside them for a while, but toward morning he wandered into the hall and began nibbling at the tatters of wallpaper that hung loose from the wall. He nibbled thoughtfully and rather daintily like someone eating celery at a dinner party.