15

The Safe

Portia made one of those peculiar sounds that signify sudden and total astonishment: something between a gasp and a squeal.

"It's it!"

"Mrs. Brace-Gideon's real live safe!" Lucy whispered in awe.

"I don't believe it, though. I just simply can't believe it," Portia said.

"But it's real! My goodness, Portia, look at all those numbers and little metal doorknobs. Why, it's the realest-looking thing I ever saw!"

Portia gave a leap. "Come on, then, we must tell Mother.... Mother, oh, MOTHER!" shouted Portia, flinging the door open, storming along the hall and down the stairs.

"Mo—ther!!"

"Portia, for heaven's sake!" exclaimed Mrs. Blake, emerging from the kitchen. "You sound like a trumpeting elephant! What in the world is the matter!"

"We've found the safe, Mother! We've finally found it!"

"You've found the what?" said Mrs. Blake, utterly confused.

"Oh Mother, the safe! Mrs. Brace-Gideon's wall safe! The thing she kept her money in; you know."

"Her safe? Really? Are you sure?" said Mrs. Blake.

"Oh, Mother," Portia repeated impatiently. "Come and see for your own self!" She took her mother's hand and pulled her, hurried her, to the stairs.

"It's really true, Mrs. Blake, it really is, it's really true," Lucy kept babbling, right at their heels as they ran up the steps. And right at her heels came the members of the Indian band, with their mouths full of cooky.

"In the bathroom?" expostulated Mrs. Blake. "How could it possibly be in the b—" But by then they had ushered her in, and she saw what they had seen: the medicine cabinet swung out from the wall, and in the wall the little metal door with its nickel knobs and dials, the little door that had been hidden all these years!

"Why, I never—I absolutely never—" murmured Mrs. Blake, almost at a loss for words. Then she said: "How do you suppose we'll get it open?"

Portia gave another of her leaps.

"Julian!" she exclaimed. "Jule has the combination, Mother; he found it in the helmet!"

"He found it where?" begged poor Mrs. Blake, but nobody was there to tell her; already they were tumbling and galumphing down the stairs.

The big front door flew open and stayed open. The children, led by Portia, streamed across the lawn.

"Jul—i—an! Oh, Jule!" roared Portia, marveling even as she did so at her own lung power.

But the big boys were nowhere to be seen; nowhere within earshot, either, obviously.

"They must have gone to Gone-Away; where else would they go?" suggested Lucy.

So off they all went, jog-trotting along the wooded drive; Portia first, her tooth braces blinking and her bangs standing straight up in the wind; Lucy next, with her curls bouncing; and chugging along behind them came the Indian braves, still eating as they ran.

As it happened, Julian and Tom and Joe had spent the afternoon at Gone-Away, helping Mr. Payton build a stronger goatpen for the vagrant Uncle Sam.

It was always interesting to build things at Gone-Away, because no new material was ever used; it was necessary to improvise, and this in itself was a challenge.

The goatpen in the first place had been an ingenious barricade contrived of chicken wire, old doors, old bedsprings. And today the boys and Mr. Payton had reinforced it with more doors, more bedsprings, and a length of railing from the Delaneys' fallen porch. They had also added a wrought-iron gate from somebody's forgotten driveway; and that gave it a touch of elegance.

"Ma-a-a-a," said Uncle Sam, sounding perfectly disgusted. He stood on his hind legs and stared at them balefully through the wrought-iron gate.

"Yes indeed, sir, yes indeed," Mr. Payton replied to him. "This will keep you in your place for a while. Until the next time. For there will be a next time, I'll be bound," he added to the boys. "Uncle Sam has the soul of a vagabond and the ingenuity of a born thief."

He removed his hat and blotted his forehead with a handkerchief.

"Let us go to my house and have a drink of water. Later my sister may have something better to offer."

For some reason Mr. Payton's kitchen pump seemed to produce the coldest, clearest water in the region, like the water of a mountain spring. Perhaps, Julian thought, it was because they usually drank it after they had been working hard or playing hard.

When the boys had had all they wanted, they drifted into Mr. Payton's living room. It was very different from his sister's: barer. There were many books piled up in piers, but very little furniture. There were no pictures on the walls; only a piece of tacked-up wrapping paper with words printed on it, and none of them could read the words because they were written in Latin.

Joe and Tom sat on the horsehair sofa, looking blank and comfortably worn-out. Julian, on the floor, had propped his back against the bed, and Mr. Payton, bolt-upright on one of his bolt-upright little chairs, was lighting his pipe, coaxing it and coaxing it along.

Julian sighed contentedly. It's good to work hard, then to rest, he thought. His aimless eye caught sight again of the black letters painted on the wrapping paper.

"Uncle Pin, what is that Latin thing?" he asked. "What does it say? I've wondered for a long time, but I keep forgetting to ask."

Mr. Payton puff-puffed his pipe; it had come to life now, and he turned his head to look at the paper on the wall.

"The words are very old, Julian. They were written hundreds of years ago by a man who loved nature and who became a saint: Saint Francis of Assisi. It's sort of a hymn of praise. They call it a canticle: the canticle of the sun....

"'Praised be my Lord with all his creatures,' it says, 'and especially our brother the sun who brings us the day and who brings us the light; fair is he, and shining with very great splendor: O Lord he signifies to us thee!

"'Praised be my Lord for our sister the moon, and for the stars, which he has set clear and lovely in heaven.

"'Praised be my Lord for our brother the wind, and for air and cloud, calms and all weathers, by which thou upholdest in life all creatures.

"'Praised be my Lord for our sister water, who is very serviceable unto us, and humble and precious and clean.

"'Praised be my Lord for our brother fire, through whom thou givest his light in the darkness; and he is bright and pleasant, and very mighty and strong....'"

Mr. Payton read on in his calm quiet voice till he came to the end of the canticle.

"I like that part about brothers and sisters," Tom said. "The sun would be a brother, and the moon would be a sister...."

Nobody else said anything. Fatly had come to settle by Julian's leg. He had turned on his purr at middle register; not his loudest purr. Still, they could hear it.

And then they heard something else.

"Julian! Oh, Ju—ule!"

Julian sighed and stood up.

"Girls," he remarked, and went to the door. He opened it wide and leaned out. "Here we are, Porsh," he called, "here at Uncle Pin's."

Portia and Lucy and the Indians blew breathless into the house.

"We've found it, Jule." Portia panted. "We've found the safe!"

"The safe? You mean the safe?"

"Mrs. Brace-Gideon's!" contributed Lucy.

"Oh, brother!" Julian shouted. "But I have to go home to get the paper with the combination on it. I'll hurry back—I've got my bike—and I'll meet you at your house—" Halfway through the door he turned back. "Where did you find it, though?"

When Portia told him he said, "See? What did I say?" Then he vanished.

"You come with us, Uncle Pin," Portia said. "And let's get Aunt Minnehaha, too. We should all be there together when he opens it."

Julian, on reaching home, leaped from his bike, allowing it to fall, leaped into the house, shouting the news to his mother, and attained his room without having touched the stairs; or so it seemed.

There followed a few minutes of panic because he could not remember what he had done with the slip. Collections of birds' nests and sea shells were toppled about, drawers were pulled out and their contents clawed into a muddle, the pockets of his coats and trousers were searched; and then, of course, he found the slip exactly where he had put it: in plain sight, on his worktable, with a fossil stone to hold it down.

"I'll drive you back, Julian," his mother said. "It will save time, and besides I wouldn't miss this event for anything!"

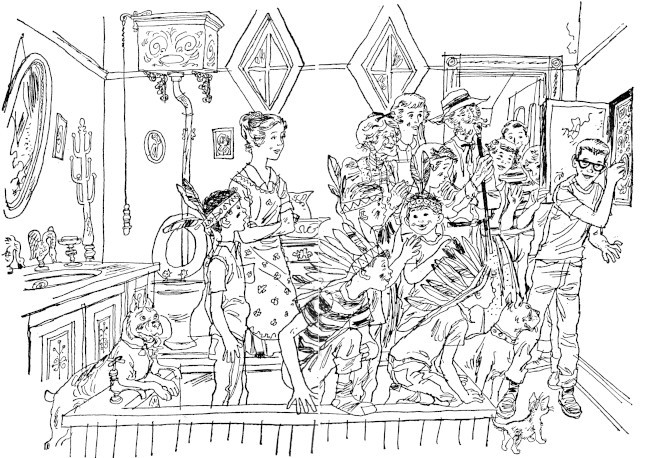

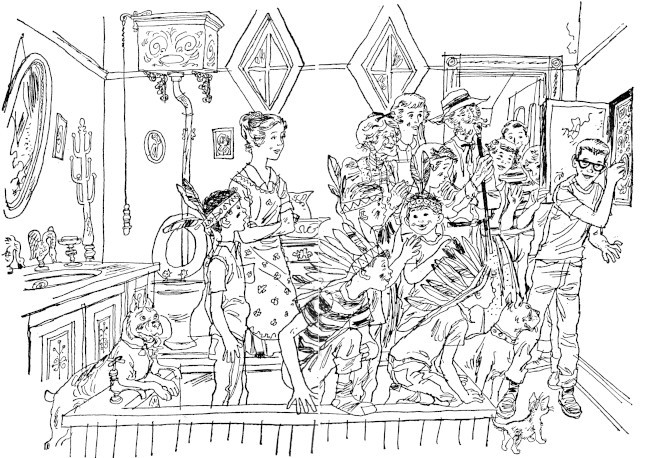

It was a peculiar gathering to assemble in anybody's bathroom: two pretty women, five biggish children, assorted; five smallish ones, boys, wearing war feathers; one elderly lady dressed in the fashion of the Gay Nineties; one elderly gentleman with a distinguished beard and clothes not much more recent. Also two dogs and one small kitten. Though the room was large, it wasn't really large enough. The Indians obligingly removed their shoes and stood in the bathtub.

"Now," said Julian.

They waited breathlessly.

Julian carefully wiped his fingers with a handkerchief. (He had seen someone do this on TV.) Then he lightly touched the T-shaped hand on the dial. He looked as though he had been doing this sort of thing all his life.

"Now it's on zero, see?" He said. "That's where it has to be first. So. Here we go. Six turns to the right. One ... two ... three ... four ... five ... six. There, I heard the tumblers fall. Now two turns to the left. One ... two...."

Slowly, meticulously, he followed exactly the instructions on the slip of paper. At the last, after the "three whole turns R to eight," he paused dramatically.

"Want me to go on?"

"Oh, hurry up! Hurry up!"

Julian grinned, put out his hand, and opened the small heavy door. Inside the safe there was still another little door with a key in its lock. Above, and on either side, the shelves and pigeonholes were empty.

"Turn the key! Turn the key!"

So Julian turned the key and opened the door to the interior cupboard of the safe. Everyone pressed forward in a bunch. And then there was a sort of collective groan in the room because that little cupboard, like Mother Hubbard's famous one, was bare; bare even of dust.

"Well, I didn't think there'd be anything in it. I never did," said Portia, disappointed to be right.

"But what about that little drawer under the door?" Lucy asked.

"I can't get it open. It's locked and the key's gone."

"Try the one in the cupboard door...."

But the key didn't fit.

"Perhaps I can force it," Mr. Payton said, coming forward. "Since returning to Gone-Away, I have become fairly expert at breaking locks. Had to. Couldn't get into the Big House any other way." He turned to Mrs. Blake. "With your permission?"

"But of course, of course!"

With the head of his heavy walking stick Mr. Payton dealt the lock a number of sharp blows.

"I think perhaps now ... but I need something to pull it open with. There is no handle."

Foster, with great presence of mind, stepped out of the bathtub and handed Mr. Payton Baron Bloodshed's buttonhook, which had been spending the summer in his pocket with other curious items.

"Maybe this'll do."

"Ah, excellent, Foster, thank you. Yes, yes indeed.... Look!"

Mr. Payton pulled open the little drawer, which was lined with blue plush and filled with small labeled packets.

Hands reached out; Foster's grubby ones among them.

"No, wait a bit, wait a bit," Mr. Payton commanded. "I think the privilege should go to Mrs. Blake."

But Mrs. Blake said: "I think it should go to Lucy and Portia. They're the ones who found the safe."

Portia's fingers were shaking when she lifted the first packet out and read the label: "Mamma's Garnet Parure."

"What's a parure?" said Foster.

It turned out to be a set of jewelry: a garnet necklace with earrings and brooch to match, sparkling and dark and clear as wine.

"How beautiful!"

"Mine says: 'Great-Aunt Sophronisba's Brooch with Uncle Walter's Hair!'" Lucy announced.

This turned out to be a large gold-framed pin enclosing a small fine-woven mat of dark brown hair!

"Oh, yes, hair jewelry was much the fashion in my grandmother's day," Mrs. Cheever said.

"Did they ever use teeth?" Foster wanted to know, thinking of his own old front ones, but Mrs. Cheever said she thought not.

The girls in greatest excitement went on opening the little packets. Mrs. Cheever, Mrs. Blake, and Aunt Hilda hovered about them, fascinated. Mr. Payton was interested, too. But the boys were rather disappointed; jewelry didn't mean much to them.

"Here's 'Great-Grandfather Dadware's Signet Ring!'" said Portia, holding up a massive ring with a carnelian intaglio set in gold.

"And here are 'Great-Grandmother Dadware's Cameo Bracelets,'" said Lucy, displaying the lovely things: circlets of ovals, and on each oval a little face was exquisitely carved.

There were necklaces of paste and pinchbeck and jet and amber; there were gold earrings and silver ones, and ones made out of coral and of turquoise. There were bracelets woven of golden wire, and many brooches, and fine-link chains and lockets of gold and onyx. There were seed pearls all gone black with age, and cold jade beads from which the silken cord had rotted away. Many of the things were beautiful, and some were ruined. All were very old.

The last packet contained the prettiest thing of all. "Great-great Grandmother's Betrothal Ring." It looked like a cobweb heavy-set with dew.

"Rose diamonds!" Aunt Hilda said. "Barbara, it can't be later than the eighteenth century, and probably it's older!"

"Then I suppose these things were left behind in the safe just as the furniture was left in the attic," Mrs. Blake speculated. "Partly because they were too good to throw away; partly because of family sentiment. And none of them to Mrs. Brace-Gideon's own personal taste."

"Oh, no indeed! Indeed they would not have been," Mrs. Cheever asserted. "They would never have been costly enough. Or showy enough. When it came to jewelry, Mrs. Brace-Gideon inclined toward the flamboyant, didn't she, Pin?"

"Had a diamond that looked like a hotel doorknob," Mr. Payton said. "I remember it well."

"And that emerald I told you about. And rubies; great clumps and clots of rubies all mobbed together; and a pin, a gold pin shaped like an eagle, with ruby eyes; and a water-lily pin as big as my hand, made out of opals.... Oh, no, these never would have suited her!"

"Thank fortune," Mrs. Blake said, as she had said so often this summer.

The girls, dripping with jewels, were delighted with all that they had found.

"Well, I'll tell you one thing, Portia," Lucy said. "I'll never believe another word of Madame Vavasour's, not even about our characters. This has been the most exciting day I've ever spent!"

"I know. Just look at all these lovely things. What could be more wonderful to find?"

"Money," Foster answered promptly. "I wish it had been some old-time money. Or an old-time gun, or two guns, or some skulls and bones, or something interesting!"