CHAPTER VI

WILLIAM THE MONEY-MAKER

THE rain poured ceaselessly upon the old barn where the Outlaws were assembled. They had meant to spend the afternoon birds-nesting, and they had continued to birds-nest in spite of the steady downpour till Ginger had torn such a large hole in his knickers that as he pathetically remarked, “S’all very well for you. ’S only rainin’ on your clothes. But it’s rainin’ right on to me through my hole an’ it’s jolly cold an’ I’m goin’ home.”

His threat of going home was hardly serious. It was not likely that any of the Outlaws would waste the precious hours of a half-holiday in a place so barren of any hope of adventure as home.

“All right,” said William the leader (upon whose stern and grimy countenance the rain had traced little channels of cleanliness) testily. “All right. My goodness, what a fuss you make about a bit of rain on your bare skin. What would you do if you was a Red Indian an’ had to be out of doors all weathers and nearly all bare skin?”

“Well, it doesn’t rain in Red Indian climits,” said Ginger. “So there! Don’t you be too clever. It doesn’t rain in Red Indian climits.”

William was nonplussed for a moment, then he summoned his fighting spirit.

“How do you know?” he said. “You ever been there? You ever been to a Red Indian climit? Well, I din’t know you’d ever been to a Red Indian climit. But I’m very int’rested to hear it. It’s very int’restin’ an’ funny you din’t get killed an’ eat, I mus’ say.”

William’s weapon of heavy sarcasm always proved rather bewildering to his friends.

“I don’ see that it matters whether I’ve been to a Red Indian climit or not,” said Ginger stoutly, “’it wun’t stop me feelin’ wet now if I had, would it?”

“Well, what would you do if you was a diver,” went on William, “’f you’re so frightened of gettin’ a bit wet? P’raps what with knowin’ so much about Red Indian climits you’ll say it’s not wet in the sea. Of course ’f you say it’s not wet in the sea we’ll all b’lieve you. Oh yes, we’ll all b’lieve you ’f you say it’s not wet in the sea. I s’pose that’s wot you’ll be sayin’ next—that it’s not wet in the sea—with knowin’ so much about Red Indian climits——”

At this moment there came a redoubled torrent of rain and turning up their sodden collars the Outlaws all ran to the old barn which was the scene of many of their activities.

“I’m s’prised to see you run like that,” said Ginger to William. “I should’ve thought you’d have liked gettin’ wet the way you talk about divers an’ Red Indians.”

William shut the door of the barn and pushed his wet hair out of his eyes.

“I thought it was you wot knew all about Red Indian climits an’ the sea not bein’ wet,” he said severely. “Seems to me you don’t know wot you are talkin’ about sometimes. One minute you say the sea’s not wet——”

“I never said the sea wasn’t wet,” said Ginger. “You sim’ly don’t listen to what I do say.—You jus’ keep on talkin’ an’ talkin’ yourself an’ you don’ listen prop’ly to wot other folks say. You get it all wrong. You go on talkin’ and talkin’ about Red Indians an’ divers——”

But Henry and Douglas, the other two Outlaws, were tired of the subject.

“Oh, do shut up!” said Henry irritably.

“Who shut up?” said William aggressively.

“Both of you,” said Douglas.

Ginger and William hurled themselves upon the other two and there followed one of those scrimmages in which the Outlaws delighted. It ended by Ginger sitting on Henry and William on Douglas, and all felt a little warmer and dryer and less irritable. The subjects of Red Indians and divers were by tacit consent dropped.

It was raining harder than ever. The water was pouring in through the roof at the other end of the barn.

“What’ll we do?” said Ginger disconsolately rolling off his human perch.

Their afternoon so far had not been encouraging. They had with characteristic optimism aimed at collecting forty eggs before tea. They had all sustained severe falls from trees, they were wet through, they were scratched and torn and bruised, and the result was one cracked thrush’s egg from a deserted nest, which Ginger subsequently dropped and then inadvertently trod upon while climbing through a hedge. This incident had made Ginger unpopular for a time. It had drawn forth the rough diamonds of William’s sarcasm.

“’S very kind of you, I’m sure. Yes, we took all that trouble jus’ so’s you could have the pleasure of treadin’ on it. Oh, yes, we feel quite paid for all the trouble we took now you’ve been kind enough to tread on it. Can we get you anythin’ else to tread on? I’m sure it’s very nice for the poor bird to think it’s had all the trouble of layin’ that egg jus’ for you to tread on——”

This rhetoric had resulted in a fight between William and Ginger, at the end of which both had rolled into a ditch. The ditch was not a dry ditch, but they were both so wet already that the immersion made little difference.

“Do?” said Henry indignantly. “Jus’ tell us what there is to do shut up in this ole place. Do? Huh!”

“I know what we can do,” said William suddenly, “we can make up a tale turn an’ turn about.”

They were sitting on the two wooden packing cases with which they had furnished their meeting place. A small rivulet ran between, having its source just beneath the hole in the roof at the other end of the barn and flowing out under the door. The Outlaws carelessly dabbled their feet in it as it passed. Their drooping spirits revived at William’s suggestion.

“A’ right,” said Henry, “you start.”

“A’ right,” said William modestly. “I don’ mind startin’. Once there was a man wot got cast upon a desert island.”

“Why?” said Ginger, “why was he cast upon a desert island?”

“’F you’re goin’ to keep on int’ruptin’ askin’ silly questions——” began William sternly.

“A’ right,” said Ginger pacifically. “A’ right. Go on.”

“He was cast upon a desert island,” repeated William, “an’ the desert island was full of savage cannibals what chased him round an’ round the island till he climbed a tree an’ they all s’rounded the tree utterin’ fierce yells——”

“What was they yellin’?” said Henry with interest.

“How could anyone tell what they was yelling without knowin’ the langwidge?” said William impatiently. “Do you know the cannibal langwidge? No, an’ the man din’t, so how could he tell wot they was yellin’?”

“Well the one wot’s tellin’ the tale oughter know,” said Henry doggedly, “You oughter know. The one wot’s tellin’ the tale oughter know everythin’ in the tale——”

“Well, I do,” said William crushingly, “but I’m not goin’ to tell you wot they was yellin’, so there. An’ when you’ve all kin’ly finished int’ruptin’ I’ll kin’ly go on. They was all beneath the tree utterin’ fierce yells wot I know wot they meant but wot I’m not goin’ to tell you, when he took a great big jump right off the tree, splash into the sea again an’ caught hold of a whale wot was jus’ passing and got on its back an’ held tight on by its fins——”

“I don’t think a whale’s got fins,” said Douglas dubiously.

“I don’ care whether other whales’ve got fins or not,” said William firmly, “this one haddem anyway. An’ he kept rearin’ up an’ turnin’ over so’s to shake the man off but the man held tight and—now, Henry, go on.”

“A’ right,” said Henry, “well he went on an’ on on the whale’s back till he came to a ship an’ he jumped up on to it from the whale’s back——”

“He couldn’t have done,” said Douglas firmly.

“What?” said Henry.

“Couldn’t have done. Couldn’t have jumped from a whale’s back to a ship. A ship’s high.”

“Well, he did,” said Henry, “so it’s no use talkin’ about whether he could or not. If he did he could, I should think.” William’s sarcasm was infectious. “Well, he found it was a pirate ship an’ they put him in irons an’ made him walk the plank an’ just when he got to the end of the plank—now Ginger, go on.”

“Well, you’ve gottim in a nice mess, I mus’ say,” said Ginger bitterly, “an’ I s’pose you want me to gettim out of it—chased by cannibals an’ now walkin’ a plank! Well you gottim into it an’ I’m not goin’ to bother with him. I din’t start it an’ I don’t like it. I’d rather have soldiers an’ fightin’ an’ that sort of a tale. An’ wot can I do with him walkin’ the plank? I’m jus’ about tired of that man. An’ he’s not even gotta name. Well, jus’ as he got to the end of the plank he fell in an’ the whale ate him up an’ he died.”

“It isn’t fair,” said Douglas indignantly, “gettin’ him dead before I’ve had my turn. What’m I goin’ to do?”

“You can tell about someone catchin’ the whale an’ findin’ his dead body inside,” said Ginger calmly.

“Oh, can I?” said Douglas, “well I’m not goin’ to.”

“No, ’cause you can’t,” jeered Ginger. “You can’t finish it however we left it.”

“Oh, couldn’t I?” said Douglas.

They closed in combat. William and Henry watched dispassionately.

Douglas’s collar had completely broken loose from its moorings and two of the already existing tears in Ginger’s coat had been extended to meet each other. They sat down again on the packing cases.

“Still raining,” said Henry morosely.

“I bet your mother’ll say something about that tear,” said William to Ginger severely.

“Well, you bet wrong then,” said Ginger, “’cause she’s gone to London to see the Exhibition.”

“Fancy goin’ to London to see an ole exhibition,” said William scornfully, “What she see there?”

“Oh, natives,” said Ginger, “black uns, you know, an’ native places an’ jugs an’ things made by natives.”

“That all?”

“Well, there’s amusements an’ things too, but that’s all really,” said Ginger. “You pay money an’ jus’ see ’em’ an’ that’s all.”

“Crumbs!” said William. His face was set in deep scowling thought for a minute, then a light broke over it. “I say,” he said, “let’s have a nexhibition—let’s get a nexhibition up. Well, ’f Ginger’s mother ’ll go all the way to London to see a nexhibition it’d—well, it’d be savin’ folks’ money to givvem a nexhibition here.”

“We’ve done things like that,” said Henry morosely. “We’ve got up shows an’ things an’ they’ve always turned out wrong.”

“We’ve never got up a nexhibition,” said William, “a nexhibition’s quite diff’rent. It couldn’t go wrong an’ we’d make ever so much money.”

“I don’t b’lieve in your ways of makin’ money,” said Henry, “something always goes wrong.”

“A’ right,” said William sternly, “don’t be in it. Keep out of it.”

“Oh, no,” said Henry hastily, “I’d rather be in it even if it goes wrong. I’d rather be in a thing that turns out wrong than not be in anything at all.”

“Where’ll we get natives?” said Ginger.

“Oh, anyone can look like a native,” said William carelessly. “That’s easy ’s easy.”

“What’ll we call it?” said Douglas.

“The London one’s called Wembley,” said Ginger with an air of pride in his wide knowledge.

“What about ‘The Little Wembley’?” said Henry.

“Well that’s a silly thing to do!” said William sternly, “tellin’ ’em it’s littler than Wembley before they’ve come to it. Even if it is littler than Wembley we needn’t tellem so.”

“Let’s call it just Wembley,” suggested Douglas.

“No,” said William, “it would be muddlin’ havin’ ’em both called by the same name. Folks wouldn’t know which they was talkin’ about.”

“When I stayed with my aunt,” said Ginger slowly, “there was a place called a Picture Palace de lucks. Let’s call it Wembley de lucks.”

“What’s de lucks mean,” said William suspiciously.

“I ’spect it means sorter good luck,” said Ginger.

“All right,” said William graciously, “that’ll do all right for a name. Now how’re we goin’ to let people know about it?”

“How did they let people know about the other Wembley?” said Henry.

“They put advertisements in the papers an’ things,” said Ginger who was beginning to consider himself the greatest living authority on the subject of the Wembley Exhibition.

“We can’t do that,” said Henry, “the papers sim’ly wouldn’t print ’em if we wrote ’em. I know ’cause I once sent somethin’ to a paper an’ they sim’ly didn’t print it.”

“Well, then,” said William undaunted, “we’ll write letters to people. They’ll have to read ’em. We’ll stick ’em through their letter boxes an’ they’ll have to read ’em case they was somethin’ important. An’ I say, it’s nearly stopped rainin’. Let’s see ’f we can find any more eggs.”

II

A week later the Outlaws were sitting round the large wooden table of the one-time nursery in Ginger’s house. In a strained silence they wrote out the letter drafted by William, a copy of which was before each of them. The table was covered with ink stains. Their hair, their faces, their tongues, their collars, their fingers were covered with ink. Most of them wrote slowly and laboriously with ink-stained tongues protruding between ink-stained teeth.

“DEAR SIR or MADDAM (ran the copy),

On Satterdy we are going to have a Wembley not the one in London but one here so as to save you fairs and other exspences there will be natifs in natif coschume with natif potts and ammusments and other things which are secrits till the day entranse will be one penny exsit free ammusments are one penny hopping to have the pleshure of your compny,

YOURS TRUELY,

THE WEMBLY COMITTY.

P.S. It is a secrit who we are.

P.P.S. It will probly be in the feeld next the barn but notises will be put up latter.”

When the notes had been written the Outlaws were both physically and mentally exhausted. They could run and wrestle and climb trees all day without feeling any effects, but one page of writing always had the peculiar effect of exhausting their strength and spirits. As William said, “It’s havin’ to hold an uncomfortable pen an’ keep on thinkin’ an’ lookin’ at paper an’ sittin’ without a change. It’s—well I’d rather be a Red Indian where there aren’t no schools.”

The notices were distributed by the Outlaws personally after dark in order the better to conceal their identity. They did not deliver notices to their own families or the friends of their families. Their own families were apt to be suspicious and not very encouraging. The Outlaws regarded their families as stumbling blocks placed in their paths by a malicious Fate.

At last, spent and weary and ink-stained, they bade each other good-night.

“Well, it oughter turn out all right with all the trouble we’re takin’ over it,” said Ginger rather bitterly. “I feel wore out with writin’ an’ writin’ an’ walkin’ an’ walkin’ and stickin’ things through the letter boxes. I feel sim’ly wore out.”

“I think I’m goin’ to be sick soon,” said Henry with a certain gentle resignation, “swallerin’ all that ink.”

“Well, no one asked you to swaller ink,” said William whose position of responsibility was making him slightly irritable. “You talk ’s if we’d wanted you to swaller ink. It’s not done any good to us you swallerin’ ink. ’F you’ve been wastin’ Ginger’s ink swallerin’ it then you don’ need to blame us. It’s not Ginger’s fault that you’ve swallered his ink, is it?”

“Yes, an’ it is,” said Henry, “it got all up his pen an’ on to my fingers an’ then I had to keep lickin’ ’em to get it off an’ that’s wot’s made me feel sick. Well, ornery ink doesn’t do that. It’s somethin’ wrong with Ginger’s ink I should say. It——”

“Henry!” called an irate maternal voice through the dusk, “when are you coming in? It’s hours past your bedtime.”

The Outlaws scattered hastily....

III

The Outlaws had decided to hold the exhibition in Farmer Jenks’ field behind the barn. Farmer Jenks was the Outlaws’ most implacable foe. He frequently chased the Outlaws from his fields with shouts and imprecations and stones and dogs. He had once uttered the intriguing threat to William that he would “cut his liver out.” This had deeply impressed the Outlaws and William had felt proud of the fame it won him. He could not resist haunting Farmer Jenks’ lands because the chase that always ensued was so much more exciting than an ordinary chase. “Well, he’s not cut it out yet,” he used to say proudly after each escape.

But just now Farmer Jenks was away staying with a brother and Mrs. Jenks was confined to bed, and the farm labourers quite wisely preferred to leave the Outlaws as far as possible to their own devices. So the Outlaws were coming more and more to regard that field of Farmer Jenks’ as their private property.

The afternoon of the exhibition was unusually warm. The exhibition opened at 2 o’clock. To the stile that led from the road was attached a notice

THIS WAY T

O WEMBLY D

E LUCKS

and on the hole in the hedge by which spectators were to enter Farmers Jenks’ field was pinned another notice.

THIS WAY T

O WEMBL

EY DE L

UCKS.

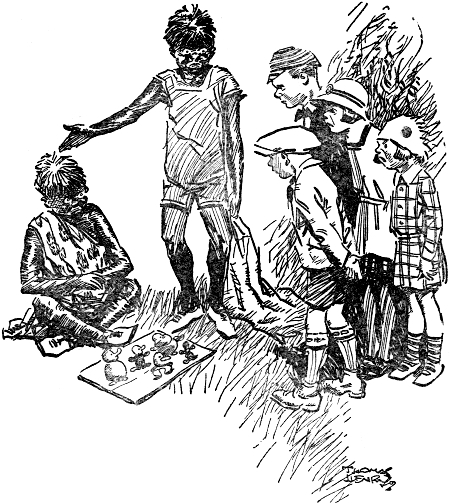

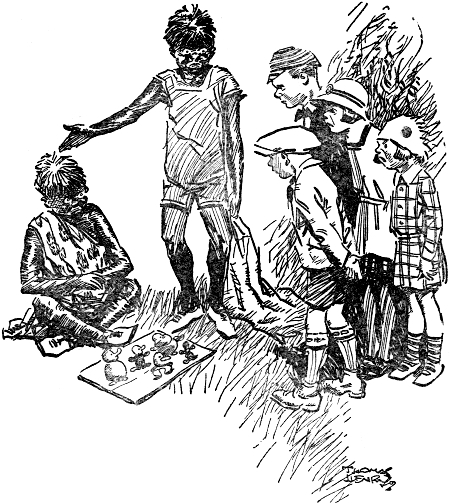

At 2.30 which was the time advertised for the opening a small and suspicious-looking group of four school children had gathered at the stile. William, his face and bare legs thickly covered with boot blacking and tightly clutching an old sack across his chest, met them, frowning sternly.

“One penny each please!” he said aggressively. “An’ I’m part of the exhibition an’ I’m a native an’ come this way please an’ hurry up.”

There was a certain amount of bargaining on the part of the tallest boy who refused to give more than a halfpenny, saying that he could black himself and look in the looking glass for nothing if that was all there was ’n a nexhibition, and there was a small scene caused by a little girl who refused to pay anything at all, and yet insisted on accompanying them in spite of William’s stern remonstrances, and finally followed in the wake of the party howling indignantly, “I’m not a cheat. You’re a cheat—you narsy ole black boy an’ I won’ give you a penny an’ I will come to your narsy old show, so there! Boo-oo-oo-oo!”

William shepherded his small flock through the hole in the hedge. Then he took his stand behind a little piece of wood on which were ranged pieces of half-dry plasticine tortured into strange shapes. With a dramatic gesture William flung aside his piece of sacking and stood revealed in an old pale blue bathing costume that had belonged to his sister Ethel in her childhood.

“Now you can look at me first,” he said in a deep unnatural voice. “I’m a native of South Africa dressed in native coschume an’ this here is native orn’ments made by me an’ you can buy the orn’ments for a penny each,” he added not very hopefully.

“Yes,” said the tallest boy, “an’ we can do without buyin’ ’em equ’ly well.”

“Yes, an’ I’d jus’ as soon you din’ buy ’em,” said William proudly but untruthfully, “’cause they’re worth more’n a penny an’ I’ll very likely get a shillin’ each for ’em before the exhibition’s over.”

“Huh!” said the boy scornfully. “Well, wot’s next? ’S not worth a penny so far.”

“’F it’d been worth a penny so far,” said William, “d’you think I’d’v let you see it all for a penny. Why don’ you try to talk sense?”

The small girl at the tail of the procession was still sobbing indignantly.

“I’m not a cheat. Boo-hoo-hoo an’ I won’t give the narsy boy my Sat’day penny. I won’t. I wanter buy sweeties wiv it an’ I’m not a cheat, boo-hoo-hoo!”

“A’ right,” said the goaded William. “You’re not then an’ don’t then an’ shut up.”

“You’re being very wude to me,” said the young pessimist with a fresh wail.

Beyond William were three other sacking-shrouded figures, each behind a piece of wood on which were displayed small objects.

“TALK AUSTRALIAN!” COMMANDED WILLIAM.

“MONKEY, FLUKY, TIM-TIM,” SAID GINGER.

“CALL THAT AUSTRALIAN?” SAID THE AUDIENCE

INDIGNANTLY.

“Now I’m a guide,” said William returning to his hoarse, unnatural voice. “This way please ladies an’ gentlemen an’ we’d all be grateful if the lady would kin’ly shut up.” This remark occasioned a fresh outburst of angry sobs on the part of the aggrieved lady. “This,” taking off the first sackcloth with a flourish and revealing Ginger dressed in an old tapestry curtain, the exposed parts of his person plentifully smeared with moist boot blacking, “this is a native of Australia, and these are native wooden orn’ments made by him. Talk Australian, Native.”

The confinement under the sacking had been an austere one and the day was hot and streams of perspiration mingling with the blacking gave Ginger’s countenance a mottled look. Before him were wooden objects roughly cut into shapes that might have represented almost anything. As examples of art they belonged decidedly to the primitive School.

“Go on, Ging—Native, I mean. Talk Australian,” commanded William.

“Monkey, donkey, fluky, tim-tim,” said Ginger, “an’ crumbs, isn’t it hot?”

“Call that Australian?” said the audience indignantly.

“Well,” said William loftily, “he’s nat’rally learnt a bit of English comin’ over here.” Then, taking up one of the unrecognisable wooden shapes and handing it to the little girl: “Here, you can have that if you’ll shut up an’ it’s worth ever so much, I can tell you. It’s valu’ble.”

She took it, beaming with smiles through her tears.

“I ’spect some of you’d like to buy some?” said William.

His audience hastily and indignantly repudiated the suggestion.

“What do I do now?” said Ginger.

“You jus’ wait for the next lot,” said William covering him up with the sacking. Ginger sat down again muttering disconsolately about the heat beneath his sacking.

Henry was a Canadian and Douglas was an Egyptian. Both were pasted with blacking and both shone with streaky moisture. Henry wore a large cretonne cushion cover and Douglas wore a smock that had been made for use in charades last Christmas. Both obligingly talked in their native language. Douglas, who was learning Latin, said, “Bonus, bona, bonum, bonum, bonam, bonum,” to the fury and indignation of his audience.

In front of Henry were balls of moist clay; in front of Douglas were twigs tied together in curious shapes. The sightseers refused all William’s blandishing persuasions to buy.

“Well, it’s you I’m thinking of,” said William. “’F you go home without takin’ these int’restin’ things made by natives you’ll be sorry and then it’ll be too late. An’ you mayn’t ever again see ’em to buy an’ you’ll be sorry. An’ if you bought ’em you could put ’em in a museum an’—an’ they’d always be int’restin’.”

The smallest boy was moved by William’s eloquence to pay a penny for a clay ball, then promptly regretted it and demanded his penny back.

It was while this argument was going on that Violet Elizabeth appeared.

“Wanter be a native like Ginger—all black,” she demanded loudly.

William, who was harassed by his argument with the repentant purchaser of native ware, turned on her severely.

“You oughter pay a penny comin’ into this show,” he said.

“I came in a different hole, a hole of my own so I’m not going to,” said Violet Elizabeth, “an’ I wanter be a native like Ginger an’ Henry an’ Douglas—all lovely an’ black.”

“Well, you can’t be,” said William firmly.

Tears filled her eyes and she lifted up her voice.

“Wanterbean-a-a-tive,” she screamed.

“All right,” said William desperately. “Be a native. I don’t care. Be a native. Get the blacking from Ginger. I don’t care. Be one an’ don’t blame me. The next is the amusements, ladies an’ gentlemen.”

There were three amusements. The first consisted in climbing a tree and lowering oneself from the first branch by a rope previously fastened to it by William. The second consisted in being wheeled once round the field in a wheelbarrow by William. The third consisted in standing on a plank at the edge of the pond and being gently propelled into the pond by William. The entrance fee to each was one penny.

“Yes,” said the tallest boy indignantly, “an’ s’pose we fall off the plank into the water?”

“That’s part of the amusement,” said William wearily.

The smallest boy decided after much thought to have a penny ride in a wheelbarrow....

IV

Mrs. Bott was walking proudly up the lane. She had in train, not an earl exactly, but distantly related to an earl. At any rate he was County—most certainly County. So far County had persistently resisted the attempts of Mrs. Bott to “get in” with it. Mrs. Bott had met him and captured him and was bringing him home to tea. She had brushed aside all his excuses. He walked beside her miserably, looking round for some way of escape. Already in her mind’s eye Mrs. Bott was marrying Violet Elizabeth to one of his nephews (she came to the reluctant conclusion that he himself would be rather too old when Violet Elizabeth attained a marriageable age) and was killing off all his relations in crowds by earthquakes or floods or wrecks or dread diseases to make quite sure of the earldom. Ivory charmeuse for Violet Elizabeth of course and the bridesmaids in pale blue georgette....

Suddenly they came to a paper notice pinned very crookedly on a stile in the hedge:

******

The distant relation to the peer of the realm brightened. He stroked his microscopic moustache.

“I say!” he said, “sounds rather jolly, what?”

Mrs. Bott who had assumed an expression of refined disgust hastily exchanged it for one of democratic tolerance.

“Yars,” she said in her super-county-snaring accent, “doesn’t it? We always trai to taike an interest in the activities of the village.”

“I say, I think I’ll just go in and see,” he said.

He hoped that it would throw her off but as a ruse it was a failure.

“Oh yars!” she said, “Let’s! I think it’s so good for the village to feel the upper clarses take an interest in them.”

The hole in the hedge proved too small for Mrs. Bott’s corpulency, but the depressed connection of the peerage found a larger one further up which afforded quite a broad passage when the hedge was held back.

They entered the field.