CHAPTER XIV

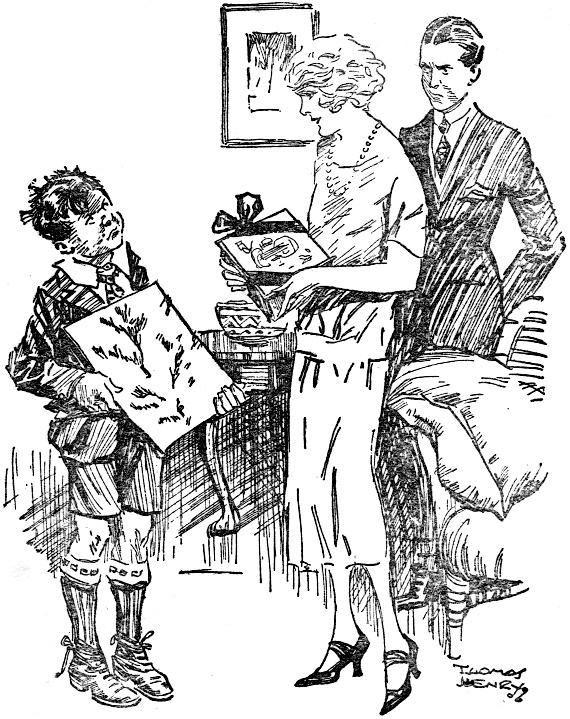

WILLIAM AND SAINT VALENTINE

WILLIAM was, as not infrequently, under a cloud. His mother had gone to put some socks into one of his bedroom drawers and had found that most of the drawer space was occupied by insects of various kinds, including a large stag beetle, and that along the side of the drawer was their larder, consisting of crumby bits of bread and a little pool of marmalade.

“But it eats marmalade,” pleaded William. “The stag beetle does. I know it does. The marmalade gets a little less every day.”

“Because it’s soaking into the wood,” said Mrs. Brown sternly. “That’s why. I don’t know why you do such things, William!”

“But they’re doing no harm,” said William. “They’re friends of mine. They know me. The stag beetle does anyway and the others will soon. I’m teaching the stag beetle tricks.... Honest, it knows me and it knows its name. Call ‘Albert’ to it and see if it moves.”

“I shall do nothing of the sort, William. Take the creatures out at once. I shall have to scrub the drawers and have everything washed. You’ve got marmalade and crumbs all over your socks and handkerchiefs.”

“Well, I moved ’em right away when I put them in. They’ve sort of spread back.”

“Why ever didn’t you keep the things outside?”

“I wanted to have ’em and play with ’em at nights an’ mornin’s.”

“And here’s one of them dead!”

“I hope it didn’t die of anythin’ catchin’,” said William anxiously. “I shun’t like Albert to get anythin’. There’s no reason for ’em to die. They’ve got plenty of food an’ plenty of room to play about in an’ air gets in through the keyhole.”

“Take them away!”

William lovingly gathered up his stag beetle and woodlice and centipedes and earwigs and took them downstairs, leaving his mother groaning over the crumby marmalady drawer....

He put them into cardboard boxes and punched holes in the tops. He put Albert, the gem of the collection, in a small box in his pocket.

Then it began to rain and he came back to the house.

There was nothing to do....

He wandered from room to room. No one was in. The only sounds were the sounds of the rain and of his mother furiously scrubbing at the drawer upstairs. He wandered into the kitchen. It was empty. On the table by the window was a row of jam jars freshly filled and covered. His mother had made jam that morning. William stood by the table, half sprawling over it, resting his head on his hands and watched the rain disconsolately. There was a small knife on the table. William took it up and, still watching the rain, absent-mindedly “nicked” in all the taut parchment covers one by one. He was thinking of Albert. As he nicked in the parchment, he was vaguely conscious of a pleasant sensation like walking through heaped-up fallen leaves or popping fuschia buds or breaking ice or treading on nice fat acorns.... He was vaguely sorry when the last one was “nicked.”

Then his mother came in.

“William!” she screamed as she saw the jam jars.

“What’ve I done now?” said William innocently. “Oh ... those! I jus’ wasn’t thinking what I was doin’. Sorry!”

Mrs. Brown sat down weakly on a kitchen chair.

“I don’t think anyone ever had a boy like you ever before William,” she said with deep emotion. “The work of hours.... And it’s after time for you to get ready for Miss Lomas’ class. Do go, and then perhaps I’ll get a little peace!”

******

Miss Lomas lived at the other end of the village. She held a Bible class for the Sons and Daughters of Gentlefolk every Saturday afternoon. She did it entirely out of the goodness of her heart, and she had more than once regretted the goodness of her heart since that Son of Gentlefolk known to the world as William Brown had joined her class. She had worked hard to persuade Mrs. Brown to send him. She thought that she could influence William for good. She realised when William became a regular attendant of her class that she had considerably over-estimated her powers. William could only be persuaded to join the class because most of his friends, not without much exertion of maternal authority, went there every Saturday. But something seemed to have happened to the class since William joined it. The beautiful atmosphere was destroyed. No beautiful atmosphere was proof against William. Every Saturday Miss Lomas hoped that something would have happened to William so that he could not come, and every Saturday William hoped equally fervently that something would have happened to Miss Lomas so that she could not take the class. There was something dispirited and hopeless in their greeting of each other....

William took his seat in the dining-room where Miss Lomas always held her class. He glanced round at his fellow students, greeting his friends Ginger and Henry and Douglas with a hideous contortion of his face....

Then he took a large nut out of his pocket and cracked it with his teeth.

“Not in here, William,” said Miss Lomas faintly.

“I was goin’ to put the bits of shell into my pocket,” said William. “I wasn’t goin’ to put ’em on your carpet or anything, but ’f you don’t want me to’s all right,” he said obligingly, putting nut and dismembered shell into his pocket.

“Now we’ll say our verses,” said Miss Lomas brightly but keeping a fascinated apprehensive eye on William. “William, you begin.”

“’Fraid I din’t learn ’em,” said William very politely. “I was goin’ to last night an’ I got out my Bible an’ I got readin’ ’bout Jonah in the whale’s belly an’ I thought maybe it’d do me more good than St. Stephen’s speech an’ it was ever so much more int’restin’.”

“That will do, William,” said Miss Lomas. “We’ll—er—all take our verses for granted this afternoon, I think. Now, I want to give you a little talk on Brotherly Love.”

“Who’s Saint Valentine?” said William who was burrowing in his prayer-book.

“Why, William?” said Miss Lomas patiently.

“Well, his day seems to be comin’ this month,” said William.

Miss Lomas, with a good deal of confusion, launched into a not very clear account of the institution of Saint Valentine’s Day.

“Well, I don’t think much of him ’s a saint,” was William’s verdict, as he took out another nut and absent-mindedly cracked it, “writin’ soppy letters to girls instead of gettin’ martyred prop’ly like Peter an’ the others.”

Miss Lomas put her hand to her head.

“You misunderstand me, William,” she said. “What I meant to say was— Well, suppose we leave Saint Valentine till later, and have our little talk on Brotherly Love first.... Ow-w-w!”

Albert’s box had been accidentally opened in William’s pocket, and Albert was now discovered taking a voyage of discovery up Miss Lomas’ jumper. Miss Lomas’ spectacles fell off. She tore off Albert and rushed from the room.

William gathered up Albert and carefully examined him. “She might have hurt him, throwing him about like that,” he said sternly. “She oughter be more careful.”

Then he replaced Albert tenderly in his box.

“Give us a nut,” said Ginger.

Soon all the Sons and Daughters of Gentlefolk were cracking nuts, and William was regaling them with a racy account of Jonah in the whale’s belly, and trying to entice Albert to show off his tricks....

“Seems to me,” said William at last thoughtfully, looking round the room, “we might get up a good game in this room ... something sort of quiet, I mean, jus’ till she comes back.”

But the room was mercifully spared one of William’s “quiet” games by the entrance of Miss Dobson, Miss Lomas’ cousin, who was staying with her. Miss Dobson was very young and very pretty. She had short golden curls and blue eyes and small white teeth and an attractive smile.

“My cousin’s not well enough to finish the lesson,” she said. “So I’m going to read to you till it’s time to go home. Now, let’s be comfortable. Come and sit on the hearthrug. That’s right. I’m going to read to you ‘Scalped by the Reds.’”

William drew a deep breath of delight.

At the end of the first chapter he had decided that he wouldn’t mind coming to this sort of Bible class every day.

At the end of the second he had decided to marry Miss Dobson as soon as he grew up....

******

When William woke up the next morning his determination to marry Miss Dobson was unchanged. He had previously agreed quite informally to marry Joan Crewe, his friend and playmate and adorer, but Joan was small and dark-haired and rather silent. She was not gloriously grown-up and tall and fair and vivacious. William was aware that marriage must be preceded by courtship, and that courtship was an arduous business. It was not for nothing that William had a sister who was acknowledged to be the beauty of the neighbourhood, and a brother who was generally involved in a passionate if short-lived affaire d’amour. William had ample opportunities of learning how it was done. So far he had wasted these opportunities or only used them in a spirit of mockery and ridicule, but now he determined to use them seriously and to the full.

He went to the garden shed directly after breakfast and discovered that he had made the holes in his cardboard boxes rather too large and the inmates had all escaped during the night. It was a blow, but William had more serious business on hand than collecting insects. And he still had Albert. He put his face down to where he imagined Albert’s ear to be and yelled “Albert” with all the force of his lungs. Albert moved—in fact scuttled wildly up the side of his box.

“Well, he cert’n’ly knows his name now,” said William with a sigh of satisfaction. “It’s took enough trouble to teach him that. I’ll go on with tricks now.”

He went to school after that. Albert accompanied him, but was confiscated by the French master just as William and Ginger were teaching it a trick. The trick was to climb over a pencil, and Albert, who was labouring under a delusion that freedom lay beyond the pencil, was picking it up surprisingly well. William handed him to the French master shut up in his box, and was slightly comforted for his loss by seeing the master on opening it get his fingers covered with Albert’s marmalade ration for the day, which was enclosed in the box with Albert. The master emptied Albert out of the window and William spent “break” in fruitless search for him, calling “Albert!” in his most persuasive tones ... in vain, for Albert had presumably returned to his mourning family for a much-needed “rest cure.”

“Well, I call it stealin’,” said William sternly, “takin’ beetles that belong to other people.... It’d serve ’em right if I turned a Bolshevist.”

“I don’t suppose they’d mind what you turned,” said Ginger unfeelingly but with perfect truth.

It was a half-holiday that afternoon, and to the consternation of his family William announced his intention of staying at home instead of as usual joining his friends the Outlaws in their lawless pursuits.

“But, William, some people are coming to tea,” said Mrs. Brown helplessly.

“I know,” said William. “I thought p’raps you’d like me to be in to help with ’em.”

The thought of this desire for William’s social help attributed to her by William, left Mrs. Brown speechless. But Ethel was not speechless.

“Well, of course,” she remarked to the air in front of her, “that means that the whole afternoon is spoilt.”

William could think of no better retort to this than, “Oh, yes, it does, does it? Well, I never!”

Though he uttered these words in a tone of biting sarcasm and with what he fondly imagined to be a sarcastic smile, even William felt them to be rather feeble and added hastily in his normal manner:

“’Fraid I’ll eat up all the cakes, I s’pose? Well, I will if I get the chance.”

“William, dear,” said Mrs. Brown, roused to effort by the horror of the vision thus called up, “do you think it’s quite fair to your friends to desert them like this? It’s the only half-holiday in the week, you know.”

“Oh, ’s all right,” said William. “I’ve told ’em I’m not comin’. They’ll get on all right.”

“Oh, yes, they’ll be all right,” said Ethel in a meaning voice and William could think of no adequate reply.

But William was determined to be at home that afternoon. He knew that Laurence Hinlock, Ethel’s latest admirer, was expected and William wished to study at near quarters the delicate art of courtship. He realised that he could not marry Miss Dobson for many years to come, but he did not see why his courtship of her should not begin at once.... He was going to learn how it was done from Laurence Hinlock and Ethel....

He spent the earlier part of the afternoon collecting a few more insects for his empty boxes. He was still mourning bitterly the loss of Albert. He deliberately did not catch a stag beetle that crossed his path because he was sure that it was not Albert. He found an earwig that showed distinct signs of intelligence and put it in a large, airy box with a spider for company and some leaves and crumbs and a bit of raspberry jam for nourishment. He did not give it marmalade because marmalade reminded him so poignantly of Albert....

Then he went indoors. There were several people in the drawing-room. He greeted them rather coldly, his eye roving round the while for what he sought. He saw it at last.... Ethel and a tall, lank young man sitting in the window alcove in two comfortable chairs, talking vivaciously and confidentially. William took a chair from the wall and carried it over to them, put it down by the young man’s chair, and sat down.

“DON’T YOU WANT TO GO AND PLAY WITH YOUR

FRIENDS?” ASKED THE YOUNG MAN.

There was a short, pregnant silence.

“Good afternoon,” said William at last.

“Er—good afternoon,” said the young man.

There was another silence.

“Hadn’t you better go and speak to the others?” said Ethel.

“I’ve spoke to them,” said William.

There was another silence.

“Don’t you want to go and play with your friends?” asked the young man.

“No, thank you,” said William.

Silence again.

“I think Mrs. Franks would like you to go and talk to her,” said Ethel.

“No, I don’t think she would,” said William with perfect truth.

“NO, THANK YOU,” SAID

WILLIAM.

The young man took out a shilling and handed it to William.

“Go and buy some sweets, for yourself,” he said.

William put the shilling in his pocket.

“Thanks,” he said. “I’ll go and get them to-night when you’ve all gone.”

There was another and yet deeper silence. Then Ethel and the young man began to talk together again. They had evidently decided to ignore William’s presence. William listened with rapt attention. He wanted to know what you said and the sort of voice you said it in.

“St. Valentine’s Day next week,” said Laurence soulfully.

“Oh, no one takes any notice of that nowadays,” said Ethel.

“I’m going to,” said Laurence. “I think it’s a beautiful idea. Its meaning, you know ... true love.... If I send you a Valentine, will you accept it?”

“That depends on the Valentine,” said Ethel with a smile.

“It’s the thought that’s behind it that’s the vital thing,” said Laurence soulfully. “It’s that that matters. Ethel ... you’re in all my waking dreams.”

“I’m sure I’m not,” said Ethel.

“You are.... Has anyone told you before that you’re a perfect Botticelli?”

“Heaps of people,” said Ethel calmly.

“I was thinking about love last night,” said Laurence. “Love at first sight. That’s the only sort of love.... When first I saw you my heart leapt at the sight of you.” Laurence was a great reader of romances. “I think that we’re predestined for each other. We must have known each other in former existences. We——”

“Do speak up,” said William irritably. “You’re speaking so low that I can’t hear what you’re saying.”

“What!”

The young man turned a flaming face of fury on to him. William returned his gaze quite unabashed.

“I don’ mean I want you to shout,” said William, “but just speak so’s I can hear.”

The young man turned to Ethel.

“Can you get a wrap and come into the garden?” he said.

“Yes.... I’ve got one in the hall,” said Ethel, rising.

William fetched his coat and patiently accompanied them round the garden.

******

“What do people mean by sayin’ they’ll send a Valentine, Mother?” said William that evening. “I thought he was a sort of saint. I don’ see how you can send a saint to anyone, specially when he’s dead ’n in the Prayer Book.”

“Oh, it’s just a figure of speech, William,” said Mrs. Brown vaguely.

“A figure of what?” said William blankly.

“I mean, its a kind of Christmas card only it’s a Valentine, I mean.... Well, it had gone out in my day, but I remember your grandmother showing me some that had been sent to her ... dried ferns and flowers pasted on cardboard ... very pretty.”

“Seems sort of silly to me,” said William after silent consideration.

“People were more romantic in those days,” said Mrs. Brown with a sigh.

“Oh, I’m romantic,” said William, “if that means bein’ in love. I’m that all right. But I don’ see any sense in sendin’ pasted ferns an’ dead saints and things.... But still,” determinedly, “I’m goin’ to do all the sort of things they do.”

“What are you talking about, William?” said Mrs. Brown.

Then Ethel came in. She looked angrily at William.

“Mother, William behaved abominably this afternoon.”

“I thought he was rather good, dear,” said Mrs. Brown mildly.

“What did I do wrong?” said William with interest.

“Followed us round everywhere listening to everything we said.”

“Well, I jus’ listened, din’ I?” said William rather indignantly. “I din’ interrupt ’cept when I couldn’t hear or couldn’t understand. There’s nothing wrong with jus’ listenin’, is there?”

“But we didn’t want you,” said Ethel furiously.

“Oh ... that!” said William. “Well, I can’t help people not wanting me, can I? That’s not my fault.”

Interest in Saint Valentine’s Day seemed to have infected the whole household. On February 13th William came upon his brother Robert wrapping up a large box of chocolates.

“What’s that?” said William.

“A Valentine,” said Robert shortly.

“Well, Miss Lomas said it was a dead Saint, and Mother said it was a pasted fern, an’ now you start sayin’ it’s a box of chocolates! No one seems to know what it is. Who’s it for, anyway?”

“Doreen Dobson,” said Robert, answering without thinking and with a glorifying blush.

“Oh, I say!” said William indignantly. “You can’t. I’ve bagged her. I’m going to do a fern for her. I’ve had her ever since the Bible Class.”

“Shut up and get out,” said Robert.

Robert was twice William’s size.

William shut up and got out.

******

The Lomas family was giving a party on Saint Valentine’s Day, and William had been invited with Robert and Ethel. William spent two hours on his Valentine. He could not find a fern, so he picked a large spray of yew-tree instead. There was no time to dry it, so he tried to affix it to paper as it was. At first he tried with a piece of note-paper and flour and water, but except for a generous coating of himself with the paste there was no result. The yew refused to yield to treatment. It was too strong and too large for its paper. Fortunately, however, he found a large piece of thick cardboard, about the size of a drawing-board, and a bottle of glue, in the cupboard of his father’s writing desk. It took the whole bottle of glue to fix the spray of yew-tree on to the cardboard, and the glue mingled freely with the flour and water on William’s clothing and person. Finally he surveyed his handiwork.

“Well, I don’ see much in it now it’s done,” he said, “but I’m jolly well going to do all the things they do do.”

He went to put on his overcoat to hide the ravages beneath, and met Mrs. Brown in the hall.

“Why are you wearing your coat, dear?” she said solicitously. “Are you feeling cold?”

“No. I’m just getting ready to go out to tea. That’s all,” said William.

“But you aren’t going out to tea for half an hour or so yet.”

“No, but you always say that I ought to start gettin’ ready in good time,” said William virtuously.

“Yes, of course, dear. That’s very thoughtful of you,” said Mrs. Brown, touched.

William spent the time before he started to the party inspecting his insect collection. He found that the spider had escaped and the earwig was stuck fast in the raspberry jam. He freed it, washed it, and christened it “Fred.” It was beginning to take Albert’s place in his affections.

Then he set off to Miss Lomas’ carrying his Valentine under his arm. He started out before Ethel and Robert because he wanted to begin his courtship of Miss Dobson before anyone else was in the field.

“WHAT IS IT, WILLIAM?” ASKED MISS DOBSON.

“A VALENTINE,” REPEATED WILLIAM. “MY valentine.”

Miss Lomas opened the door. She paled slightly as she saw William.

“Oh ... William,” she said without enthusiasm.

“I’ve come to tea,” William said, and added hastily, “I’ve been invited.”

“You’re rather early,” said Miss Lomas.

“Yes, I thought I’d come early so’s to be sure to be in time,” said William, entering and wiping his feet on the mat. “Which room’re we goin’ to have tea in?”

With a gesture of hopelessness Miss Lomas showed him into the empty drawing-room.

“It’s Miss Dobson I’ve really come for,” explained William obligingly as he sat down.

Miss Lomas fled, but Miss Dobson did not appear.

William spent the interval wrestling with his Valentine. He had carried it sticky side towards his coat, and it now adhered closely to him. He managed at last to tear it away, leaving a good deal of glue and bits of yew-tree still attached to his coat.... No one came.... He resisted the temptation to sample a plate of cakes on a side table, and amused himself by pulling sticky bits of yew off his coat and throwing them into the fire from where he sat. A good many landed on the hearthrug. One attached itself to a priceless Chinese vase on the mantelpiece. William looked at what was left of his Valentine with a certain dismay. Well ... he didn’t call it pretty, but if it was the sort of thing they did he was jolly well going to do it.... That was all.... Then the guests began to arrive, Robert and Ethel among the first. Miss Dobson came in with Robert. He handed her a large box of chocolates.

“A Valentine,” he said.

“Oh ... thank you,” said Miss Dobson, blushing.

William took up his enormous piece of gluey cardboard with bits of battered yew adhering at intervals.

“A Valentine,” he said.

Miss Dobson looked at it in silence. Then:

“W-what is it, William?” she said faintly.

“A Valentine,” repeated William shortly, annoyed at its reception.

“Oh,” said Miss Dobson.

Robert led her over to the recess by the window which contained two chairs. William followed, carrying his chair. He sat down beside them. Both ignored him.

“Quite a nice day, isn’t it?” said Robert.

“Isn’t it?” said Miss Dobson.

“Miss Dobson,” said William, “I’m always dreamin’ of you when I’m awake.”

“What a pretty idea of yours to have a Valentine’s Day party,” said Robert.

“Do you think so?” said Miss Dobson coyly.

“Has anyone ever told you that you’re like a bottled cherry?” said William doggedly.

“Do you know ... this is the first Valentine I’ve ever given anyone?” said Robert.

Miss Dobson lowered her eyes.

“Oh ... is it?” she said.

“I’ve been thinkin’ about love at first sight,” said William monotonously. “I got such a fright when I saw you first. I think we’re pre-existed for each other. I——”

“Will you allow me to take you out in my side-car to-morrow?” said Robert.

“Oh, how lovely!” said Miss Dobson.

“No ... pre-destinated ... that’s it,” said William.

Neither of them took any notice of him. He felt depressed and disillusioned. She wasn’t much catch anyway. He didn’t know why he’d ever bothered about her.

“Quite a lady-killer, William,” said General Moult from the hearth-rug.

“Beg pardon?” said William.

“I say you’re a lady-killer.”

“I’m not,” said William, indignant at the aspersion. “I’ve never killed no ladies.”

“I mean you’re fond of ladies.”

“I think insects is nicer,” said William dispiritedly.

He was quiet for a minute or two. No one was taking any notice of him. Then he took up his Valentine, which was lying on the floor, and walked out.

******

The Outlaws were in the old barn. They greeted William joyfully. Joan, the only girl member, was there with them. William handed her his cardboard.

“A Valentine,” he said.

“What’s a Valentine?” said Joan who did not attend Miss Lomas’ class.

“Some say it’s a Saint what wrote soppy letters to girls ’stead of gettin’ martyred prop’ly, like Peter an’ the others, an’ some say it’s a bit of fern like this, an’ some say it’s a box of chocolates.”

“Well, I never!” said Joan, surprised, “but it’s beautiful of you to give it to me, William.”

“It’s a jolly good piece of cardboard,” said Ginger, ’f we scrape way these messy leaves an’ stuff.”

William joined with zest in the scraping.

“How’s Albert?” said Joan.

After all there was no one quite like Joan. He’d never contemplate marrying anyone else ever again.

“He’s been took off me,” said William.

“Oh, what a shame, William!”

“But I’ve got another ... an earwig ... called Fred.”

“I’m so glad.”

“But I like you better than any insect, Joan,” he said generously.

“Oh, William, do you really?” said Joan, deeply touched.

“Yes—an’ I’m goin’ to marry you when I grow up if you won’t want me to talk a lot of soppy stuff that no one can understand.”

“Oh, thank you, William.... No, I won’t.”

“All right.... Now come on an’ let’s play Red Indians.”

THE END