CHAPTER VII

IN THE TOILS

AFTER her meeting with Puck the fly Maya was not in a particularly happy frame of mind. She could not bring herself to believe that he was right in everything he had said about human beings, or right in his relations to them. She had formed an entirely different conception—a much finer, lovelier picture, and she fought against letting her mind harbor low or ridiculous ideas of mankind. Yet she was still afraid to enter a human dwelling. How was she to know whether or not the owner would like it? And she wouldn’t for all the world make herself a burden to anyone.

Her thoughts went back once more to the things Cassandra had told her.

“They are good and wise,” Cassandra had said. “They are strong and powerful, but they never abuse their power. On the contrary, wherever they go they bring order and prosperity. We bees, knowing they are friendly to us, put ourselves under their protection and share our honey with them. They leave us enough for the winter, they provide us with shelter against the cold, and guard us against the hosts of our enemies among the animals. There are few creatures in the world who have entered into such a relation of friendship and voluntary service with human beings. Among the insects you will often hear voices raised to speak evil of man. Don’t listen to them. If a foolish tribe of bees ever returns to the wild and tries to do without human beings, it soon perishes. There are too many beasts that hanker for our honey, and often a whole bee-city—all its buildings, all its inhabitants—has been ruthlessly destroyed, merely because a senseless animal wanted to satisfy its greed for honey.”

That is what Cassandra had told Maya about human beings, and until Maya had convinced herself of the contrary, she wanted to keep this belief in them.

It was now afternoon. The sun was dropping behind the fruit trees in a large vegetable garden through which Maya was flying. The trees were long past flowering, but the little bee still remembered them in the shining glory of countless blossoms, whiter than light, lovely, pure, and exquisite against the blue of the heavens. The delicious perfume, the gleam and the shimmer—oh, she’d never forget the rapture of it as long as she lived.

As she flew she thought of how all that beauty would come again, and her heart expanded with delight in the glory of the great world in which she was permitted to live.

At the end of the garden shone the starry tufts of the jasmine—delicate yellow faces set in a wreath of pure white—sweet perfume wafted to Maya on the soft wings of the breeze.

And weren’t there still some trees in bloom? Wasn’t it the season for lindens? Maya thought delightedly of the big serious lindens, whose tops held the red glow of the setting sun to the very last.

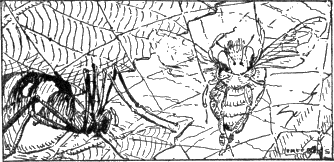

She flew in among the stems of the blackberry vines, which were putting forth green berries and yielding blossoms at the same time. As she mounted again to reach the jasmine, something strange to the touch suddenly laid itself across her forehead and shoulders, and just as quickly covered her wings. It was the queerest sensation, as if her wings were crippled and she were suddenly restrained in her flight, and were falling, helplessly falling. A secret, wicked force seemed to be holding her feelers, her legs, her wings in invisible captivity. But she did not fall. Though she could no longer move her wings, she still hung in the air rocking, caught by a marvelously yielding softness and delicacy, raised a little, lowered a little, tossed here, tossed there, like a loose leaf in a faint breeze.

Maya was troubled, but not as yet actually terrified. Why should she be? There was no pain nor real discomfort of any sort. Simply that it was so peculiar, so very peculiar, and something bad seemed to be lurking in the background. She must get on. If she tried very hard, she could, assuredly.

But now she saw a thread across her breast, an elastic silvery thread finer than the finest silk. She clutched at it quickly, in a cold wave of terror. It clung to her hand; it wouldn’t shake off. And there ran another silver thread over her shoulders. It drew itself across her wings and tied them together—her wings were powerless. And there, and there! Everywhere in the air and above her body—those bright, glittering, gluey threads!

Maya screamed with horror. Now she knew! Oh—oh, now she knew! She was in a spider’s web.

Her terrified shrieks rang out in the silent dome of the summer day, where the sunshine touched the green of the leaves into gold, and insects flitted to and fro, and birds swooped gaily from tree to tree. Nearby, the jasmine sent its perfume into the air—the jasmine she had wanted to reach. Now all was over.

A small bluish butterfly, with brown dots gleaming like copper on its wings, came flying very close.

“Oh, you poor soul,” it cried, hearing Maya’s screams and seeing her desperate plight. “May your death be an easy one, lovely child. I cannot help you. Some day, perhaps this very night, I shall meet with the same fate. But meanwhile life is still lovely for me. Good-by. Don’t forget the sunshine in the deep sleep of death.”

And the blue butterfly rocked away, drugged by the sunshine and the flowers and its own joy of living.

The tears streamed from Maya’s eyes; she lost her last shred of self-control. She tossed her captive body to and fro, and buzzed as loud as she could, and screamed for help—from whom she did not know. But the more she tossed the tighter she enmeshed herself in the web. Now, in her great agony, Cassandra’s warnings went through her mind:

“Beware of the spider and its web. If we bees fall into the spider’s power we suffer the most gruesome death. The spider is heartless and tricky, and once it has a person in its toils, it never lets him go.”

In a great flare of mortal terror Maya made one huge desperate effort. Somewhere one of the long, heavier suspension threads snapped. Maya felt it break, yet at the same time she sensed the awful doom of the cobweb. This was, that the more one struggled in it, the more effectively and dangerously it worked. She gave up, in complete exhaustion.

At that moment she saw the spider herself—very near, under a blackberry leaf. At sight of the great monster, silent and serious, crouching there as if ready to pounce, Maya’s horror was indescribable. The wicked shining eyes were fastened on the little bee in sinister, cold-blooded patience.

Maya gave one loud shriek. This was the worst agony of all. Death itself could look no worse than that grey, hairy monster with her mean fangs and the raised legs supporting her fat body like a scaffolding. She would come rushing upon her, and then all would be over.

Now a dreadful fury of anger came upon Maya, such as she had never felt before. Forgetting her great agony, intent only upon one thing—selling her life as dearly as possible—she uttered her clear, alarming battle-cry, which all beasts knew and dreaded.

“You will pay for your cunning with death,” she shouted at the spider. “Just come and try to kill me, you’ll find out what a bee can do.”

The spider did not budge. She really was uncanny and must have terrified bigger creatures than little Maya.

Strong in her anger, Maya now made another violent, desperate effort. Snap! One of the long suspension threads above her broke. The web was probably meant for flies and gnats, not for such large insects as bees.

But Maya got herself only more entangled.

In one gliding motion the spider drew quite close to Maya. She swung by her nimble legs upon a single thread with her body hanging straight downward.

“What right have you to break my net?” she rasped at Maya. “What are you doing here? Isn’t the world big enough for you? Why do you disturb a peaceful recluse?”

That was not what Maya had expected to hear. Most certainly not.

“I didn’t mean to,” she cried, quivering with glad hope. Ugly as the spider was, still she did not seem to intend any harm. “I didn’t see your web and I got tangled in it. I’m so sorry. Please pardon me.”

The spider drew nearer.

“You’re a funny little body,” she said, letting go of the thread first with one leg, then with the other. The delicate thread shook. How wonderful that it could support the great creature.

“Oh, do help me out of this,” begged Maya, “I should be so grateful.”

“That’s what I came here for,” said the spider, and smiled strangely. For all her smiling she looked mean and deceitful. “Your tossing and tugging spoils the whole web. Keep quiet one second, and I will set you free.”

“Oh, thanks! Ever so many thanks!” cried Maya.

The spider was now right beside her. She examined the web carefully to see how securely Maya was entangled.

“How about your sting?” she asked.

Ugh, how mean and horrid she looked! Maya fairly shivered with disgust at the thought that she was going to touch her, but replied as pleasantly as she could:

“Don’t trouble about my sting. I will draw it in, and nobody can hurt himself on it then.”

“I should hope not,” said the spider. “Now, then, look out! Keep quiet. Too bad for my web.”

Maya remained still. Suddenly she felt herself being whirled round and round on the same spot, till she got dizzy and sick and had to close her eyes.—But what was that? She opened her eyes quickly. Horrors! She was completely enmeshed in a fresh sticky thread which the spider must have had with her.

“My God!” cried little Maya softly, in a quivering voice. That was all she said. Now she saw how tricky the spider had been; now she was really caught beyond release; now there was absolutely no chance of escape. She could no longer move any part of her body. The end was near.

Her fury of anger was gone, there was only a great sadness in her heart.

“I didn’t know there was such meanness and wickedness in the world,” she thought. “The deep night of death is upon me. Good-by, dear bright sun. Good-by, my dear friend-bees. Why did I leave you? A happy life to you. I must die.”

The spider sat wary, a little to one side. She was still afraid of Maya’s sting.

“Well?” she jeered. “How are you feeling, little girl?”

Maya was too proud to answer the false creature. She merely said, after a while when she felt she couldn’t bear any more:

“Please kill me right away.”

“Really!” said the spider, tying a few torn threads together. “Really! Do you take me to be as big a dunce as yourself? You’re going to die anyhow, if you’re kept hanging long enough, and that’s the time for me to suck the blood out of you—when you can’t sting. Too bad, though, that you can’t see how dreadfully you’ve damaged my lovely web. Then you’d realize that you deserve to die.”

She dropped down to the ground, laid the end of the newly spun thread about a stone, and pulled it in tight. Then she ran up again, caught hold of the thread by which little enmeshed Maya hung, and dragged her captive along.

“You’re going into the shade, my dear,” she said, “so that you shall not dry up out here in the sunshine. Besides, hanging here you’re like a scarecrow, you’ll frighten away other nice little mortals who don’t watch where they’re going. And sometimes the sparrows come and rob my web.—To let you know with whom you’re dealing, my name is Thekla, of the family of cross-spiders. You needn’t tell me your name. It makes no difference. You’re a fat bit, and you’ll taste just as tender and juicy by any name.”

So little Maya hung in the shade of the blackberry vine, close to the ground, completely at the mercy of the cruel spider, who intended her to die by slow starvation. Hanging with her little head downward—a fearful position to be in—she soon felt she would not last many more minutes. She whimpered softly, and her cries for help grew feebler and feebler. Who was there to hear? Her folk at home knew nothing of this catastrophe, so they couldn’t come hurrying to her rescue.

Suddenly down, in the grass, she heard some one growling:

“Make way! I’m coming.”

Maya’s agonized heart began to beat stormily. She recognized the voice of Bobbie, the dung-beetle.

“Bobbie,” she called, as loud as she could, “Bobbie, dear Bobbie!”

“Make way! I’m coming.”

“But I’m not in your way, Bobbie,” cried Maya. “Oh dear, I’m hanging over your head. The spider has caught me.”

“Who are you?” asked Bobbie. “So many people know me. You know they do, don’t you?”

“I am Maya—Maya, the bee. Oh please, please help me!”

“Maya? Maya?—Ah, now I remember. You made my acquaintance several weeks ago.—The deuce! You are in a bad way, if I must say so myself. You certainly do need my help. As I happen to have a few moments’ time, I won’t refuse.”

“Oh, Bobbie, can you tear these threads?”

“Tear those threads! Do you mean to insult me?” Bobbie slapped the muscles of his arm. “Look, little girl. Hard as steel. No match for that in strength. I can do more than smash a few cobwebs. You’ll see something that’ll make you open your eyes.”

Bobbie crawled up on the leaf, caught hold of the thread by which Maya was hanging, clung to it, then let go of the leaf. The thread broke, and they both fell to the ground.

“That’s only the beginning,” said Bobbie.—“But Maya, you’re trembling. My dear child, you poor little girl, how pale you are! Now who would be so afraid of death? You must look death calmly in the face as I do. So. I’ll unwrap you now.”

Maya could not utter a syllable. Bright tears of joy ran down her cheeks. She was to be free again, fly again in the sunshine, wherever she wished. She was to live.

But then she saw the spider coming down the blackberry vine.

“Bobbie,” she screamed, “the spider’s coming.”

Bobbie went on unperturbed, merely laughing to himself. He really was an extraordinarily strong insect.

“She’ll think twice before she comes nearer,” he said.

But there! The vile voice rasped above them:

“Robbers! Help! I’m being robbed. You fat lump, what are you doing with my prey?”

“Don’t excite yourself, madam,” said Bobbie. “I have a right, haven’t I, to talk to my friend. If you say another word to displease me, I’ll tear your whole web to shreds. Well? Why so silent all of a sudden?”

“I am defeated,” said the spider.

“That has nothing to do with the case,” observed Bobbie. “Now you’d better be getting away from here.”

The spider cast a look at Bobbie full of hate and venom; but glancing up at her web she reconsidered, and turned away slowly, furious, scolding and growling under her breath. Fangs and stings were of no avail. They wouldn’t even leave a mark on armor such as Bobbie wore. With violent denunciations against the injustice in the world, the spider hid herself away inside a withered leaf, from which she could spy out and watch over her web.

Meanwhile Bobbie finished the unwrapping of Maya. He tore the network and released her legs and wings. The rest she could do herself. She preened herself happily. But she had to go slow, because she was still weak from fright.

“You must forget what you have been through,” said Bobbie. “Then you’ll stop trembling. Now see if you can fly. Try.”

Maya lifted herself with a little buzz. Her wings worked splendidly, and to her intense joy she felt that no part of her body had been injured. She flew slowly up to the jasmine flowers, drank avidly of their abundant scented honey-juice, and returned to Bobbie, who had left the blackberry vines and was sitting in the grass.

“I thank you with my whole heart and soul,” said Maya, deeply moved and happy in her regained freedom.

“Thanks are in place,” observed Bobbie. “But that’s the way I always am—always doing something for other people. Now fly away. I’d advise you to lay your head on your pillow early to-night. Have you far to go?”

“No,” said Maya. “Only a short way. I live at the edge of the beech-woods. Good-by, Bobbie, I’ll never forget you, never, never, so long as I live. Good-by.”