THE TWELFTH CHAPTER

MEDICINE AND MAGIC

ERY, very quietly, making sure that no one should see her, Polynesia then slipped out at the back of the tree and flew across to the prison.

ERY, very quietly, making sure that no one should see her, Polynesia then slipped out at the back of the tree and flew across to the prison.

She found Gub-Gub poking his nose through the bars of the window, trying to sniff the cooking-smells that came from the palace-kitchen. She told the pig to bring the Doctor to the window because she wanted to speak to him. So Gub-Gub went and woke the Doctor who was taking a nap.

“Listen,” whispered the parrot, when John Dolittle’s face appeared: “Prince Bumpo is coming here to-night to see you. And you’ve got to find some way to turn him white. But be sure to make him promise you first that he will open the prison-door and find a ship for you to cross the sea in.”

“This is all very well,” said the Doctor. “But it isn’t so easy to turn a black man white. You speak as though he were a dress to be re-dyed. It’s not so simple. ‘Shall the leopard change his spots, or the Ethiopian his skin,’ you know?”

“I don’t know anything about that,” said Polynesia impatiently. “But you must turn this coon white. Think of a way—think hard. You’ve got plenty of medicines left in the bag. He’ll do anything for you if you change his color. It is your only chance to get out of prison.”

“Well, I suppose it might be possible,” said the Doctor. “Let me see—,” and he went over to his medicine-bag, murmuring something about “liberated chlorine on animal-pigment—perhaps zinc-ointment, as a temporary measure, spread thick—”

Well, that night Prince Bumpo came secretly to the Doctor in prison and said to him,

“White Man, I am an unhappy prince. Years ago I went in search of The Sleeping Beauty, whom I had read of in a book. And having traveled through the world many days, I at last found her and kissed the lady very gently to awaken her—as the book said I should. ’Tis true indeed that she awoke. But when she saw my face she cried out, ‘Oh, he’s black!’ And she ran away and wouldn’t marry me—but went to sleep again somewhere else. So I came back, full of sadness, to my father’s kingdom. Now I hear that you are a wonderful magician and have many powerful potions. So I come to you for help. If you will turn me white, so that I may go back to The Sleeping Beauty, I will give you half my kingdom and anything besides you ask.”

“Prince Bumpo,” said the Doctor, looking thoughtfully at the bottles in his medicine-bag, “supposing I made your hair a nice blonde color—would not that do instead to make you happy?”

“No,” said Bumpo. “Nothing else will satisfy me. I must be a white prince.”

“You know it is very hard to change the color of a prince,” said the Doctor—“one of the hardest things a magician can do. You only want your face white, do you not?”

“Yes, that is all,” said Bumpo. “Because I shall wear shining armor and gauntlets of steel, like the other white princes, and ride on a horse.”

“Must your face be white all over?” asked the Doctor.

“Yes, all over,” said Bumpo—“and I would like my eyes blue too, but I suppose that would be very hard to do.”

“Yes, it would,” said the Doctor quickly. “Well, I will do what I can for you. You will have to be very patient though—you know with some medicines you can never be very sure. I might have to try two or three times. You have a strong skin—yes? Well that’s all right. Now come over here by the light—Oh, but before I do anything, you must first go down to the beach and get a ship ready, with food in it, to take me across the sea. Do not speak a word of this to any one. And when I have done as you ask, you must let me and all my animals out of prison. Promise—by the crown of Jolliginki!”

So the Prince promised and went away to get a ship ready at the seashore.

When he came back and said that it was done, the Doctor asked Dab-Dab to bring a basin. Then he mixed a lot of medicines in the basin and told Bumpo to dip his face in it.

The Prince leaned down and put his face in—right up to the ears.

He held it there a long time—so long that the Doctor seemed to get dreadfully anxious and fidgety, standing first on one leg and then on the other, looking at all the bottles he had used for the mixture, and reading the labels on them again and again. A strong smell filled the prison, like the smell of brown paper burning.

At last the Prince lifted his face up out of the basin, breathing very hard. And all the animals cried out in surprise.

For the Prince’s face had turned as white as snow, and his eyes, which had been mud-colored, were a manly gray!

When John Dolittle lent him a little looking-glass to see himself in, he sang for joy and began dancing around the prison. But the Doctor asked him not to make so much noise about it; and when he had closed his medicine-bag in a hurry he told him to open the prison-door.

Bumpo begged that he might keep the looking-glass, as it was the only one in the Kingdom of Jolliginki, and he wanted to look at himself all day long. But the Doctor said he needed it to shave with.

Then the Prince, taking a bunch of copper keys from his pocket, undid the great double locks. And the Doctor with all his animals ran as fast as they could down to the seashore; while Bumpo leaned against the wall of the empty dungeon, smiling after them happily, his big face shining like polished ivory in the light of the moon.

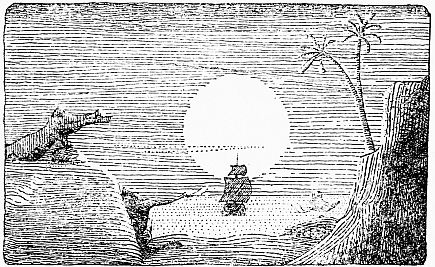

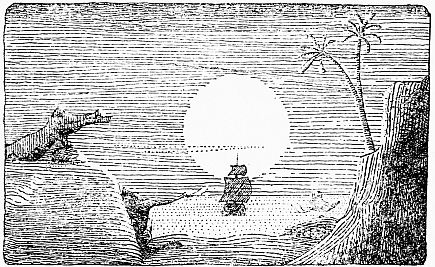

When they came to the beach they saw Polynesia and Chee-Chee waiting for them on the rocks near the ship.

“I feel sorry about Bumpo,” said the Doctor. “I am afraid that medicine I used will never last. Most likely he will be as black as ever when he wakes up in the morning—that’s one reason why I didn’t like to leave the mirror with him. But then again, he might stay white—I had never used that mixture before. To tell the truth, I was surprised, myself, that it worked so well. But I had to do something, didn’t I?—I couldn’t possibly scrub the King’s kitchen for the rest of my life. It was such a dirty kitchen!—I could see it from the prison-window.—Well, well!—Poor Bumpo!”

“Oh, of course he will know we were just joking with him,” said the parrot.

“They had no business to lock us up,” said Dab-Dab, waggling her tail angrily. “We never did them any harm. Serve him right, if he does turn black again! I hope it’s a dark black.”

“But he didn’t have anything to do with it,” said the Doctor. “It was the King, his father, who had us locked up—it wasn’t Bumpo’s fault.... I wonder if I ought to go back and apologize—Oh, well—I’ll send him some candy when I get to Puddleby. And who knows?—he may stay white after all.”

“The Sleeping Beauty would never have him, even if he did,” said Dab-Dab. “He looked better the way he was, I thought. But he’d never be anything but ugly, no matter what color he was made.”

“Still, he had a good heart,” said the Doctor—“romantic, of course—but a good heart. After all, ‘handsome is as handsome does.’”

“I don’t believe the poor booby found The Sleeping Beauty at all,” said Jip, the dog. “Most likely he kissed some farmer’s fat wife who was taking a snooze under an apple-tree. Can’t blame her for getting scared! I wonder who he’ll go and kiss this time. Silly business!”

Then the pushmi-pullyu, the white mouse, Gub-Gub, Dab-Dab, Jip and the owl, Too-Too, went on to the ship with the Doctor. But Chee-Chee, Polynesia and the crocodile stayed behind, because Africa was their proper home, the land where they were born.

And when the Doctor stood upon the boat, he looked over the side across the water. And then he remembered that they had no one with them to guide them back to Puddleby.

The wide, wide sea looked terribly big and lonesome in the moonlight; and he began to wonder if they would lose their way when they passed out of sight of land.

But even while he was wondering, they heard a strange whispering noise, high in the air, coming through the night. And the animals all stopped saying Good-by and listened.

The noise grew louder and bigger. It seemed to be coming nearer to them—a sound like the Autumn wind blowing through the leaves of a poplar-tree, or a great, great rain beating down upon a roof.

And Jip, with his nose pointing and his tail quite straight, said,

“Birds!—millions of them—flying fast—that’s it!”

And then they all looked up. And there, streaming across the face of the moon, like a huge swarm of tiny ants, they could see thousands and thousands of little birds. Soon the whole sky seemed full of them, and still more kept coming—more and more. There were so many that for a little they covered the whole moon so it could not shine, and the sea grew dark and black—like when a storm-cloud passes over the sun.

And presently all these birds came down close, skimming over the water and the land; and the night-sky was left clear above, and the moon shone as before. Still never a call nor a cry nor a song they made—no sound but this great rustling of feathers which grew greater now than ever. When they began to settle on the sands, along the ropes of the ship—anywhere and everywhere except the trees—the Doctor could see that they had blue wings and white breasts and very short, feathered legs. As soon as they had all found a place to sit, suddenly, there was no noise left anywhere—all was quiet; all was still.

And in the silent moonlight John Dolittle spoke:

“I had no idea that we had been in Africa so long. It will be nearly Summer when we get home. For these are the swallows going back. Swallows, I thank you for waiting for us. It is very thoughtful of you. Now we need not be afraid that we will lose our way upon the sea.... Pull up the anchor and set the sail!”

“Crying bitterly and waving till the ship was out of sight”

When the ship moved out upon the water, those who stayed behind, Chee-Chee, Polynesia and the crocodile, grew terribly sad. For never in their lives had they known any one they liked so well as Doctor John Dolittle of Puddleby-on-the-Marsh.

And after they had called Good-by to him again and again and again, they still stood there upon the rocks, crying bitterly and waving till the ship was out of sight.