CHAPTER VI

“KIDNAPPERS”

THERE was quite a flutter in the village when the d’Arceys came to the Grange. A branch of the d’Arcey family, you know. Lord d’Arcey and Lady d’Arcey and Lady Barbara d’Arcey. Lady Barbara was seven years of age. She was fair, frilly, fascinating. Lady d’Arcey engaged a dancing-master to come down from London once a week to teach her dancing. They invited several of the children of the village to join. They invited William. His mother was delighted, but William—freckled, untidy, and seldom clean—was horrified to the depth of his soul. No entreaties or threats could move him. He said he didn’t care what they did to him; he said they could kill him if they liked. He said he’d rather be killed than go to an ole dancing class anyway, with that soft-looking kid. Well, he didn’t care who her father was. She was a soft-looking kid, and he wasn’t going to no dancing class with her. Wildly ignoring the rules that govern the uses of the negative, he frequently reiterated that he wasn’t going to no dancing class with her. He wouldn’t be seen speaking to her, much less dancing with her.

His mother almost wept.

“You see,” she explained to Ethel, William’s grown-up sister, “it puts us at a sort of disadvantage. And Lady d’Arcey is so nice, and it’s so kind of them to ask William!”

William’s sister, however, took a wholly different view of the matter.

“It might put them,” she said, “a good deal more against us if William went!”

William’s mother admitted that there was something in that.

*****

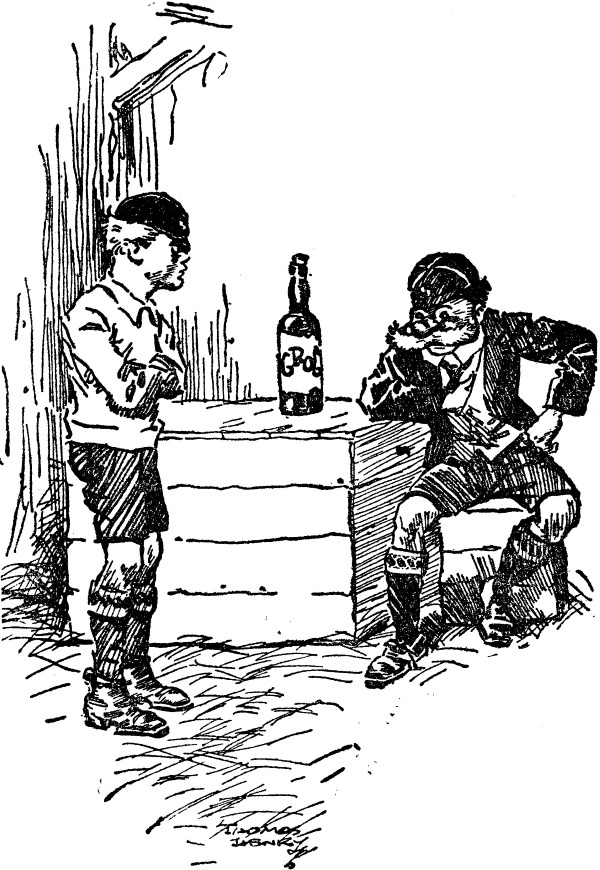

WILLIAM LAY IN THE LOFT—HIS CHIN RESTING ON

HIS HANDS, READING.

William lay in the loft, reclining at length on his front, his chin resting on his hands. He was engaged in reading. On one side of him stood a bottle of liquorice water, which he had made himself; on the other was a large slab of cake, which he had stolen from the larder. On his freckled face was the look of scowling ferocity that it always wore in any mental effort. The fact that his jaws had ceased to work, though the cake was yet unfinished, testified to the enthralling interest of the story he was reading.

“Black-hearted Dick dragged the fair maid by the wrist to the captain’s cave. A bottle of grog stood at the captain’s right hand. The captain slipped a mask over his eyes, and smiled a sinister smile. He twirled his long black moustachios with one hand.

“‘Unhand the maiden, dog,’ he said.

“Then he swept her a stately bow.

“‘Fair maid,’ he said, ‘unless thy father bring me sixty thousand crowns to-night, thy doom is sealed. Thou shalt swing from yon lone pine-tree!’

“The maiden gave a piercing scream. Then she looked closely at the masked face.

“‘Who—who art thou?’ she faltered.

“Again the captain’s sinister smile flickered beneath the mask.

“‘Rudolph of the Red Hand,’ he said.

“At these terrible words the maiden swooned into the arms of Black-hearted Dick.

“‘A-ha,’ said the grim Rudolph, with a sneer. ‘No man lives who does not tremble at those words.’

“And again that smile curved his dread lips, as he looked at the yet unconscious maiden.

“For well he knew that the sixty thousand crowns would be his that even.

“‘Let her be treated with all courtesy—till to-night,’ he said as he turned away.”

William heaved a deep sigh and took a long draught of liquorice water.

It seemed an easy and wholly delightful way of earning money.

*****

“They’re awfully nice people,” said Ethel the next day at breakfast, “and it is so kind of them to ask us to tea.”

“Very,” said Mrs. Brown, “and they say, ‘Bring the little boy’.”

The little boy looked up, with the sinister smile he had been practising.

“Me?” he said. “Ha!”

He wished he had a mask, because, though he felt he could manage the smile quite well, the narrative had said nothing about the expression of the upper part of Rudolph of the Red Hand’s face. However, he felt that his customary scowl would do quite well.

“You’ll come, dear, won’t you?” said Mrs. Brown sweetly.

“I wouldn’t make him,” said Ethel nervously. “You know what he’s like sometimes.”

Mrs. Brown knew. William—a mute, scowling protest—was no ornament to a drawing-room.

“But wouldn’t you like to meet the little girl?” said Mrs. Brown persuasively.

“Huh!” ejaculated William.

The monosyllable looks weak and meaningless in print. As William pronounced it, it was pregnant with scorn and derision and sinister meaning. He curled imaginary moustachios as he uttered it. He looked round upon his assembled family. Then he uttered the monosyllable again with a yet more sinister smile and scowl. He wondered if Rudolph of the Red Hand had a mother who tried to make him go out to tea. He decided that he probably hadn’t. Life would be much simpler if you hadn’t.

With another short, sharp “Ha!” he left the room.

*****

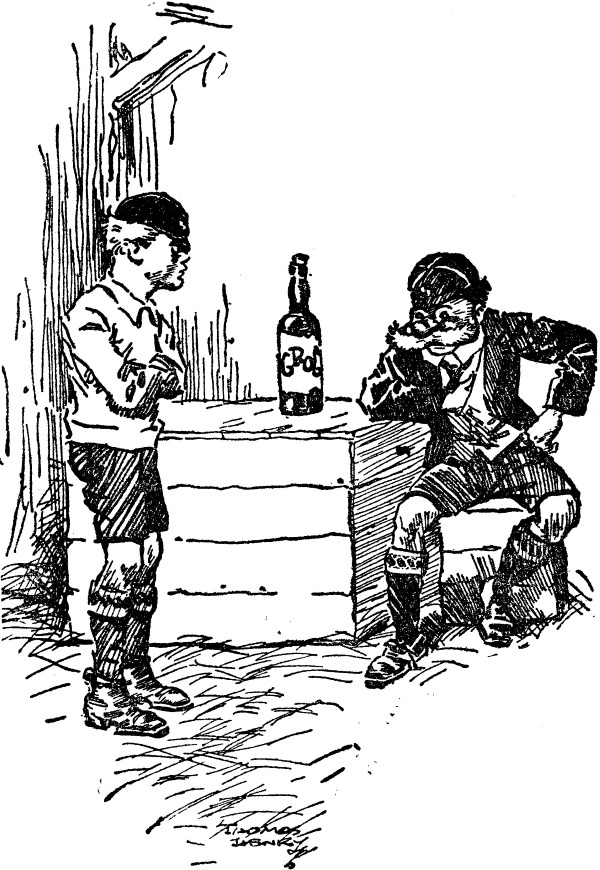

William sat on an old packing-case in a disused barn.

Before him stood Ginger, who shared the same classroom in school and pursued much the same occupations and recreations out of school. They were not a popular couple in the neighbourhood.

William was wearing a mask. The story had not stated what sort of a mask Rudolph of the Red Hand had worn, but William supposed it was an ordinary sort of mask. He had one that he’d bought last Fifth of November, and it seemed a pity to waste it. Moreover, it had the advantage of having moustachios attached. It covered his nose and cheeks, leaving holes for his eyes. It represented fat, red, smiling cheeks, an enormous red nose, and fluffy grey whiskers. William, on looking at himself in the glass, had felt a slight misgiving. It had been appropriate to the festive season of November 5th, but he wondered whether it was sufficiently sinister to represent Rudolph of the Red Hand. However, it was a mask, and he could turn his lips into a sinister smile under it, and that was the main thing. He had definitely and finally embraced a career of crime. On the table before him stood a bottle of liquorice water with an irregularly printed label: GROG. He looked round at his brave.

“Black-hearted Dick,” he said, “you gotter say, ‘Present.’”

He was rather vague as to how outlaws opened their meetings, but this seemed the obvious way.

“Present,” said Ginger, “an’ it’s not much fun if it’s all goin’ to be like school.”

“Well, it’s not,” said William firmly, “an’ you can have a drink of grog—only one swallow,” he added anxiously, as he saw Black-hearted Dick throwing his head well back preparatory to the draught.

“That was a jolly big one,” he said, torn between admiration at the feat and annoyance at the disappearance of his liquorice water.

“All right,” said Ginger modestly. “I’ve gotter big throat. Well, what we goin’ to do first?”

“BLACK-HEARTED DICK,” HE SAID, “YOU’VE GOTTER

SAY ‘PRESENT.’”

William adjusted his mask, which was not a very good fit, and performed the sinister smile.

“We gotter kidnap someone first,” he said.

“Well, who?” said Ginger.

“Someone who can pay us money for ’em.”

“Well, who?” said Ginger irritably.

William took a deep draught of liquorice water.

“Well, you can think of someone.”

“I like that,” said Ginger, in tones of deep dissatisfaction. “I like that. You set up to be captain and wear that thing, and drink up all the liquorice water——”

“Grog,” William corrected him, wearily.

“Well, grog, an’ then you don’t know who we’ve gotter kidnap. I like that. Might as well be rat hunting or catching tadpoles or chasin’ cats, if you don’t know what we’ve gotter do.”

William snorted and smiled sneeringly beneath his bilious-looking mask.

“Huh!” he said. “You come with me and I’ll find someone for you to kidnap right enough.”

Ginger cheered up at this news, and William took another draught of liquorice water. Then he hung up his mask behind the barn door and took out of his pocket a battered penknife.

“We may want arms,” he said; “keep your dagger handy.”

He pulled his school cap low down over his eyes. Ginger did the same, then looked at the one broken blade of his penknife.

“I don’t think mine would kill anyone,” he said. “Does it matter?”

“You’ll have to knock yours on the head with something,” said Rudolph of the Red Hand grimly. “You know we may be imprisoned, or hung, or somethin’, for this.”

“Rather!” said Ginger, with the true spirit of the bravado, “an’ I don’t care.”

They tramped across the fields in silence, William leading. In spite of his occasional exasperation, Ginger had infinite trust in William’s capacity for attracting adventure.

They walked down the road and across a stile. The stile led to a field that bordered the Grange. Suddenly they stopped. A small white figure was crawling through a gap in the hedge from the park into the field. William had come out with no definite aim, but he began to think that Fortune had placed in his way a tempting prize. He turned round to his follower with a resonant “’Sh!”, scowled at him, placed his finger on his lips, twirled imaginary moustachios, and pulled his cap low over his eyes. Through the trees inside the park he could just see the figure of a nurse on a seat leaning against a tree trunk in an attitude of repose. Suddenly Lady Barbara looked up and espied William’s fiercely scowling face.

She put out her tongue.

William’s scowl deepened.

She glanced towards her nurse on the other side of the hedge. Her nurse still slumbered. Then she accosted William.

“Hello, funny boy!” she whispered. Rudolph of the Red Hand froze her with a glance.

“Quick!” he said. “Seize the maiden and run!”

With a dramatic gesture he seized the maiden by one hand, and Ginger seized the other. The maiden was not hard to seize. She ran along with little squeals of joy.

“Oh, what fun! What fun!” she said.

Inside the barn, William closed the door and sat at his packing-case. He took a deep draught of liquorice water and then put on his mask. His victim gave a wild scream of delight and clapped her hands.

“Oh, funny boy!” she said.

William was annoyed.

“It’s not funny,” he said irritably. “It’s jolly well not funny. You’re kidnapped. That’s what you are. Unhand the maiden, dog,” he said to Ginger.

Ginger was looking rather sulky. “All right, I’m not handing her,” he said, “an’ when you’ve quite finished with the liquorice water——”

“Grog,” corrected William, sternly.

“Well, grog, then, an’ I helped to make it, p’raps you’ll let me have a drink.”

William handed him the bottle, with a flourish.

“Finish it, dog,” he said, with a short, scornful laugh.

The vibration of the short, scornful laugh caused his bacchic mask (never very secure) to fall off on to the packing-case. Lady Barbara gave another scream of ecstasy.

“Oh, do it again, boy,” she said.

William glanced at her coldly, and put on the mask again. Then he swept her a stately bow, holding on to his mask with one hand.

“Fair maid,” he said, “unless thy father bring me sixty thousand crowns by to-night, thy doom is sealed. Thou shalt swing from yon lone pine.”

He pointed dramatically out of the window to a diminutive hawthorn hedge.

The captive whirled round on one foot, fair curls flying.

“FAIR MAID,” HE SAID, “UNLESS THY FATHER BRING ME

SIXTY THOUSAND CROWNS, THOU SHALT SWING FROM YON

LONE PINE.”

“Oh, he’s going to make me a swing! Nice boy!”

William rose, majestic and stately, still cautiously holding his mask. “My name,” he said, “is Rudolph of the Red Hand.”

“Well, I’ll kiss you, dear Rudolph Hand,” she said, “if you like.”

William’s look intimated that he did not like.

“Oh, you’re shy!” said Lady Barbara, delightedly.

“Let her be treated,” William said, “with all courtesy till this even.”

“Well,” said Ginger, “that’s all right, but what we goin’ to do with her?”

William glanced disapprovingly at the maiden, who had turned the packing-case upside down and was sitting in it.

“Well, what we goin’ to do?” said Ginger. “It’s not much fun so far.”

“Well, we just gotter wait till her people send the money.”

“Well, how they goin’ to know we got her, and where she is, an’ how much we want?”

William considered. This aspect of the matter had not struck him.

“Well,” he said at last. “I s’pose you’d better go an’ tell them.”

“You can,” said Ginger.

“You’d better go,” said William, “’cause I’m chief.”

“Well, if you’re chief,” said Ginger, “you oughter go.”

The kidnapped one emitted a shrill scream.

“I’m a train,” she said. “Sh! Sh! Sh!”

“She’s not actin’ right,” said William severely; “she oughter be faintin’ or somethin’.”

“How much do we want for her?”

“Sixty thousand crowns,” said William.

“All right,” said Ginger. “I’ll stay and see she don’t get away, an’ you go an’ tell her people, an’ don’t tell anyone but her father and mother, or they’ll go gettin’ the money themselves.”

William hung up his mask behind the door and turned to Ginger, assuming the scowl and attitude of Rudolph of the Red Hand.

“All right,” he said, “I’ll go into the jaws of death, and you treat her with all courtesy till even.”

“Who’s goin’ to curtsey?” said Ginger indignantly.

“You don’t understand book talk,” said William, scornfully.

He bowed low to the maiden, who was still playing at trains.

“Rudolph of the Red Hand,” he said slowly, with a sinister smile.

The effect was disappointing. She blew him a kiss.

“Darlin’ Rudolph,” she said.

William stalked majestically across the fields towards the Grange, with one hand inside his coat, in the attitude of Napoleon on the deck of the Bellerophon.

He went slowly up the drive and up the broad stone steps. Then he rang the bell. He rang it with the mighty force with which Rudolph of the Red Hand would have rung it. It pealed frantically in distant regions. An indignant footman opened the door.

“I wish to speak to the master of the house on a life or death matter,” said William importantly.

He had thought out that phrase on the way up.

The footman looked him up and down. He looked him up and down as if he didn’t like him.

“Ho! do you!” he said. “And hare you aware as you’ve nearly broke our front-door bell?”

The echoes of the bell were just beginning to die away.

Rudolph of the Red Hand folded his arms and emitted a short, sharp laugh.

“His Lordship,” said the footman, preparing to close the door, “is hout.”

“His wife would do, then,” said Rudolph. “Jus’ tell her it’s a life an’ death matter.”

“Her Ladyship,” said the footman, “is hengaged, and hany more of your practical jokes ’ere, my lad, and you’ll hear of it.” He shut the door in William’s face.

William wandered round the house and looked in several of the windows; he had a lively encounter with a gardener, and finally, on peeping into the kitchen regions with a scornful laugh, was chased off the premises by the infuriated footman. Saddened, but not defeated, he returned across the fields to the barn and flung open the door. Ginger, panting and perspiring, was dragging the Lady Barbara in the packing-case round and round the barn by a piece of rope.

He turned a frowning face to William. A life of crime was proving less exciting than he had expected.

“Well, where’s the money?” he said, wiping his brow. “She’s jus’ about wore me out. She won’t let me stop draggin’ this thing about. An’ she keeps worryin’, sayin’ you promised her a swing.”

“He did!” said the kidnapped one shrilly.

“Well, where’s the money?” repeated Ginger. “I’ve jus’ about had enough of kidnappin’.”

“I couldn’t get the money,” said William. “I couldn’t make ’em listen properly. Let’s change, an’ me stay here an’ you go and get the money.”

“All right,” said Ginger. “I wun’t mind changing to do anything from this. What shall I say to ’em?”

“You’d better say you must speak to ’em on life or death. I said that, but they kind of didn’t listen. They’ll p’raps listen to you.”

“Well, I jolly well don’t mind goin’,” said Ginger: “she’s a wearin’ kid.”

He went out and shut the door.

“Put the funny thing on your face,” ordered Lady Barbara.

“It’s not funny,” said William coldly, as he adjusted the mask.

She danced round him, clapping her hands.

“Dear, funny boy! An’ now make me the swing.”

“I’m not goin’ to make you no swing,” said William firmly.

“If you don’t make me a swing,” she said, “I’ll sit down an’ I’ll scream an’ scream till I burst.”

She began to grow red in the face.

“There’s no rope,” said William hastily.

She pointed to a coil of old rope in a dark corner of the barn.

“That’s rope, silly,” she said.

He took it out and began to look round for a suitable and low enough tree.

“Be quick!” ordered his victim.

At last he had the rope tied up.

“Now lift me in! Now swing me! Go on! More! More! MORE! Nice, funny boy!”

She kept him at that for about half an hour. Then she demanded to be dragged round the barn in the packing-case.

“Go on!” she said. “Quicker! Quicker!”

The fine, manly spirit of Rudolph of the Red Hand was almost broken. He began to look weary and disconsolate.

When Ginger returned, Lady Barbara was wearing the mask and chasing William.

“Go on!” she said, “’tend to be frightened. ’Tend to be frightened. Go on!”

William turned to Ginger.

“Well?” he said.

Ginger looked rather dishevelled. His collar was torn away.

“You might have told me,” he said indignantly.

“What?” said William.

“Go on!” said Lady Barbara.

“That they were like wild beasts up there. They set on me soon as I said what you told me.”

“Well, did you get any money?” said William.

“Now, how could I?” said Ginger irritably, “when they set on me like wild beasts soon as I said it.”

“Go on!” said Lady Barbara.

“Well,” said Rudolph of the Red Hand, slowly. “I’m jus’ about fed up.”

“An’ you cudn’t be fed upper than I am,” replied his gallant brave.

“Well, let’s chuck it,” said William. “It’s getting tea-time, an’ we’ve got no money, an’ I’m not goin’ for it again.”

“Nor’m I,” said Ginger fervently.

“An’ I’m fed up with this kid.”

“So’m I,” said Ginger still more fervently.

“Well, let’s chuck it.”

He turned to Lady Barbara. “You can go home,” he said.

Her face fell.

“I don’t want to go home,” she said; “I’m going to stay with you always and always.”

“Well, you’re not,” said William shortly, “’cause we’re going home—so there.”

He set off with Ginger across the fields. The kidnapped one ran lightly beside them.

“I’m going where you go,” she said. “I like you.”

“WE KIDNAPPED A KID,” SAID WILLIAM, DISCONSOLATELY,

“AN’ WE CUDN’T GET ANY MONEY FOR HER, AN’ WE CAN’T

GET RID OF HER.”

They felt that her presence would be difficult to explain to their parents. Dejectedly, they returned to the barn.

“I’ll go an’ see if I can see anyone looking for her,” said William.

“Get down on your hands and knees and let me ride on your back,” shouted Lady Barbara. Ginger wearily obeyed.

William went out to the road and looked up it and down. There was no one there, except a man walking in the direction of the Grange. He smiled at the expression on William’s face.

“Hello!” he said, “feeling sick, or lost something?”

“We kidnapped a kid,” said William disconsolately, “an’ we cudn’t get any money for her, an’ we can’t get rid of her.”

The man threw back his head and laughed.

“Awkward!” he said, “by Jove—jolly awkward! I suppose you’ll have to take her home.”

He was no use.

William turned back to the barn. Lady Barbara was riding round the barn on Ginger’s back.

“Go on!” she said. “Quicker!”

Ginger turned a purple and desperate face to William.

“If you don’t do something soon,” he said, “I shall probably go mad and kill someone.”

“We’ll have to take her back,” said William grimly.

The kidnappers walked in gloomy silence; the kidnapped danced along between them, holding a hand of each.

“I’m going wherever you go,” she said; “I love you.”

Once Ginger spoke.

“You’re a nice kidnapper,” he said bitterly.

“I cudn’t help it,” said William. “It all went different in the book.”

Near the steps of the front door a lady was standing.

Ginger turned and fled at the sight of her. Lady Barbara held William’s hand fast. William hesitated till flight was impossible.

“Oh, there you are, darling,” the lady said.

“Dear, nice boy,” said Lady Barbara. “He’s been playing with me all the time. And the other—but the other’s gone. It’s been lovely. I do love him. May we keep him?”

“Darling,” said the lady, “I’ve only just heard you were lost. Nanny’s in a dreadful state. And this little boy found you and took care of you? Dear little boy!”

She bent down and kissed the outraged and horrified William. “How very kind of you to look after my little girl and bring her back so nicely. Now come and have some tea.”

She led William, too broken in spirit to resist, up the steps into the hall, then into a room. Lady Barbara still held his hand tightly. There was tea in the room and people. Horror of horrors! It was his mother and Ethel. There were confused explanations.

“And her nurse went to sleep, and she must have wandered off and got lost, and your little boy found her, and played with her, and looked after her, and brought her back for tea. Dear little man!”

A man entered—the man who had accosted William on the road. He was evidently the father of the little girl. The story was repeated to him.

“Great!” he said, looking at William with amusement and a certain sympathy in his eyes. He seemed to be enjoying the situation. William glared at him.

“An’ he rode me on his back, and gave me rides in the box, and made me a swing, and put on a funny face to make me laugh.”

“Dear little man!” crooned Lady d’Arcey.

They put him gently into a chesterfield, and Barbara sat beside him leaning against him.

“Nice boy,” she said.

Mrs. Brown and Ethel beamed proudly.

“And he pretends,” said Mrs. Brown, “not to like little girls. We misjudge children so sometimes. You’ll go to the dancing class now, won’t you, dear?” she ended archly.

“Dear little fellow!” said Lady d’Arcey.

It was only the fact that he had no weapon in his hand and that he had given up the unequal struggle against the malignancy of Fate that saved William from murder on a wholesale scale.

Barbara smiled on him fondly. Barbara’s mother smiled on him tenderly, his mother and sister smiled on him proudly, and in their midst Rudolph of the Red Hand, with rage and shame and humiliation in his heart, savagely ate his sugared cake.