CHAPTER VIII

WILLIAM ADVERTISES

A NEW sweetshop, Mallards by name, had been opened in the village. It had been the sensation of the week to William and his friends. For it sold everything a halfpenny cheaper than Mr. Moss.

It revolutionised the finances of the Outlaws. The Outlaws was the secret society which comprised William and his friends Ginger, Henry, and Douglas. Jumble, William’s disreputable mongrel, was its mascot.

The Outlaws patronised Mallards’ generously on the first Saturday of its career. William spent his whole threepence there on separate halfpennyworths. He insisted on the halfpennyworths. He said firmly that Mr. Moss always let him have halfpennyworths. In the end the red-haired young woman behind the counter yielded to him. She yielded reluctantly and scornfully. She took no interest in his choice. She asked him in a voice of bored contempt not to finger the Edinburgh Rock. She muttered as she did up his package—“waste of paper and time”—“never heard such nonsense”—“ha’porths indeed.”

William went out of the shop, placing his five minute packets in already over-full pockets and keeping out the sixth for present consumption.

“I’m not sure,” he said darkly to Ginger and Henry, who accompanied him—Douglas was away from home—“I’m not sure as I’m ever going there again—— Have a bull’s eye?—I didn’t like the way she looked at me nor spoke at me—an’ I’ve a jolly good mind not to go to Mallards next Saturday.”

“But it’s cheap,” said Ginger, taking out his package. “Have an aniseed ball?—an’ it’s cheap that matters in a shop, I should think.”

“Well, I don’t know,” said William, with an air of wisdom. “That’s all I say—I jus’ don’t know—-I jus’ don’t know that cheap’s all that matters.”

“Well, wot else matters? You tell me that,” said Henry, crunching up a bull’s eye and an aniseed ball simultaneously, and taking out his package. “Have a pear drop?—You jus’ tell me wot matters besides cheap in a shop.”

William, perceiving that the general feeling was against him, put another bull’s eye in his mouth and waxed irritable.

“Well, don’t talk about it so much,” he said. “You keep talkin’ an’ talkin’——” Then an argument occurred to him, and he brought it out with triumph. “S’pose anyone was a murderer—well, wot would cheap have to do with it?—S’pose someone wot had a shop murdered someone—well, I s’pose if they was cheap you’d say it was all right! Huh!”

With an expression of intense scorn and amusement William put the last bull’s eye into his mouth, threw away the paper, and took out the treacle toffee.

“Well, who’s she murdered?” said Ginger pugnaciously. “Jus’ ’cause she din’ want to give you ha’p’orths you go an’ say she’s murdered someone—— Well, who’s she murdered, that’s all?—you can’t go callin’ folks murderers an’ not prove who they’ve murdered. Bring out who she’s murdered—that’s all.”

William was at the moment deeply engrossed in his treacle toffee.

The red-haired girl had given it an insufficient allowance of paper, and in William’s pocket it had lost even this, and formed a deep attachment to a piece of putty which a friendly plumber had kindly given him the day before. The piece of putty was at that moment the apple of William’s eye. He detached it gently from the toffee and examined it tenderly to make sure that it was not harmed. Finally he replaced it in his pocket and put the toffee in his mouth. Then he returned to the argument.

“How can I bring out who she’s murdered if she’s murdered them. That’s a sens’ble thing to say, isn’t it? If she’s murdered ’em she’s buried ’em. Do you think folks wot murder folks leaves ’em about for other folks to bring out to show they’ve murdered ’em? You’ve not got much sense. That’s all I say. You don’t know much about murderers. Why do you keep talkin’ about murderers if you don’t know anything about ’em?”

Ginger was growing slightly bewildered. Arguments with William often left him bewildered. He was inclined, on the whole, to think that perhaps William was right, and she had murdered someone.

At this point Jumble created a diversion. Jumble loved treacle toffee, and he had caught a whiff of the divine perfume. He sat up promptly to beg for some, but the Outlaws’ mascot was seldom lucky himself. He sat up on the very edge of a ditch, and William could not resist giving him a push.

Jumble picked himself out of the bottom of the ditch and shook off the water, grinning and wagging his tail. Jumble was a sportsman. William had finished the treacle toffee, but Henry threw Jumble an aniseed ball, which he licked, rolled with his paw, and abandoned, and which Henry then carefully put back with the others in his packet. Then William threw a stick for him, and the discussion of the red-haired girl’s morals was definitely abandoned.

*****

At the corner of the road they espied Joan Crewe. Though fluffy and curled and exquisitely dressed herself, Joan adored William’s roughness and untidiness.

“Hello!” said Joan.

“Hello!” said the Outlaws.

“Have you been to Mallards’?” said Joan.

“Umph!” said the Outlaws.

“It’s a halfpenny cheaper than Moss’.”

“Yes,” said Ginger, “but William says she’s a murderer.”

“I di’n’t,” said William irritably. “You can’t understand English. That’s wot’s wrong with you. You can’t understand English. Wot I said was——”

Finding that he had entirely forgotten how the argument arose he hastily changed the subject. “Wot you’re goin’ to do now?” he said.

“Anything,” said Joan obligingly.

“Have a coco-nut lump?” said William, taking out his third bag.

“Have an aniseed ball?” said Ginger.

“Have a pear drop?” said Henry.

Joan took one of each and took out a bag from her pocket.

“Have a liquorice treasure?” she said.

Munching cheerfully they walked along the road, stopping to throw a stick for Jumble every now and then. Jumble then performed his “trick.” His “trick” was to walk between William and Ginger, a paw in each of their hands. It was a “trick” that Jumble cordially detested. He generally managed to avoid it. The word “trick” generally sent him flying towards the horizon like an arrow from a bow. But this time he was hoping that William still had some treacle toffee concealed on his person, and did not take to his heels in time. He was finally released with a kiss from Joan on the end of his nose. In joy at his freedom, he found a stick, worried it, ran after his tail, and finally darted down the road.

“Have a monkey-nut?” said William.

They partook of his last packet.

“I once heard a boy say,” said Henry solemnly, “that people who eat monkey-nuts get monkey puzzle trees growin’ out of their mouths.”

“I don’t s’pose,” said Ginger, as he swallowed his, “that jus’ a few could do it.”

“Anyway, it would be rather interestin’,” said William, “going about with a tree comin’ out of your mouth—you could slash things about with it.”

“But think of the orful pain,” said Henry dejectedly; “roots growin’ inside your stomach.”

Joan handed her monkey-nut back to William.

“I—I don’t think I’ll have one, thank you, William,” she said.

“All right,” said William, philosophically cracking it and putting it into his mouth. “I don’t mind eatin’ ’em. Let ’em start growin’ trees out of my stomach if they can.”

They were nearing a little old-fashioned sweetshop. A man in check trousers, shirt-sleeves, and a white apron stood in the doorway. Generally Mr. Moss radiated cheerfulness. To-day he looked depressed. They approached him somewhat guiltily.

“Well,” he said. “You coming to spend your Saturday money?”

“Er—no,” said William.

“We’ve spent it,” said Ginger.

“At Mallard’s,” said Henry.

“It’s—it’s a halfpenny cheaper,” said Joan.

“Well,” said Mr. Moss, “I don’t blame you. Mind, I don’t blame you. You’re quite right to go where it’s a halfpenny cheaper. You’d be foolish if you didn’t go where it’s a halfpenny cheaper. But all I say is it’s not fair on me. They’re a big company, they are, and I’m not. They’ve got shops all over the big towns they have, and I’ve not. They’ve got capital behind ’em, they have, an’ I’ve not. They can afford to give things away, an’ I can’t. I’ve always kept prices as low as I could so as jus’ to be able to keep myself on ’em, an’ I can’t lower them no further. That’s where they’ve got me. They can undercut. They don’t need to make a profit at first. An’ all I say is it’s not fair on me. They say as this here place is growin’ an’ there’s room for the two of us. Well, all I can say is not more’n ten people’s come into this here shop since they set up, an’ it’s not fair on me.”

His audience of four, clustered around his shop-door, listened in big-eyed admiration. As he stopped for breath, William said earnestly:

“Well, we won’t buy no more of their ole stuff, anyway——”

The Outlaws confirmed this statement eagerly, but Mr. Moss raised his hand. “No,” he said. “You oughter go where you get stuff cheapest. I don’t blame you. You’re quite right.”

They walked alone in silence for a little while. The memory of Mr. Moss, wistful and bewildered, with his cheerful hilarity gone, remained with them.

“I won’t go to that old Mallards’ again while I live,” said William firmly.

“Anyway, she wasn’t nice. I didn’t like her,” said Joan.

“She didn’t care what you bought,” said William indignantly. “She didn’t take any interest like wot Mr. Moss does.”

“Yes, an’ if she murders folks as William says she does——” began Ginger.

“I wish you’d shut up talking about that,” said William. “I di’n’t say she’d murdered anyone.”

“You did.”

“I di’n’t.”

“You did.”

“I di’n’t.”

“Do have another liquorice treasure,” said Joan.

Peaceful munchings were resumed.

“Anyway,” said William, returning to the matter in hand, “I’d like to do something for Mr. Moss.”

“Wot could we do?” said Ginger.

“We could stop folks goin’ to old Mallards’—’Tisn’t as if she took any int’rest in wot you buy.”

“Well, how could we stop folks goin’ to ole Mallards’?”

“Make ’em go to Mr. Moss.”

“Well, how—why don’ you say how?”

“Well, we’d have to have a meeting about it—an Outlaw meeting. Let’s have one now. Let’s go to our woodshed an’ have one now.”

Joan’s face fell.

“I can’t come, can I? I’m not an Outlaw.”

“You can be an Outlaw ally,” said William kindly. “We’ll make up a special oath, for you, an’ give you a special secret sign.”

Joan’s eyes shone.

“Oh, thank you, William darling.”

*****

Joan had taken the special oath. It had consisted of the words: “I will not betray the secrets of the Outlaws, an’ I will stick up for the Outlaws till death do us part.”

The last phrase was an inspiration of Henry’s, who had been to his cousin’s wedding the week before.

They sat down on logs or stacks of firewood or packing-cases to consider the question of Mr. Moss.

“First thing is,” said William, with a business-like frown, “we’ve got to make people go to Mr. Moss.”

“Well, how can we?” objected Ginger. “Jus’ tell me that? How can we make people go to Moss’ when Mallards’ is halfpenny cheaper?”

“Same way as big shops make people go to them—they put up notices an’ things—they say their things is better than other shops’ things, an’ folks believes ’em.”

“Well, why should folks believe ’em?” said Ginger pugnaciously. Henry was engaged upon his last few pear drops and had no time for conversation. “Why should folks b’lieve ’em when they say they’re better than other shops? An’ how can we stick up notices an’ where an’ who’ll let us stick up notices? You don’t talk sense. You’re mad, that’s wot you are. First you go about calling folks murderers when you don’t know who they’ve murdered, nor nothin’ about it, an’ then you talk about stickin’ up notices when there isn’t anyone who’d let us stick up any notices, nor anyone who’d take any notice of notices wot we stuck up nor——”

“If you’d jus’ stop talkin’,” said William, “an’ deafenin’ us all for jus’ a bit. You’ve been talkin’ an’ deafenin’ us all ever since you came out. D’you think we never want to hear anythin’ all our lives ever till death, but you talkin’ an’ deafenin’ us all? There is things that we’d like to hear ’sides you talkin’ an’ deafenin’ us all—there’s music an’ birds singing, an’—an’ other folks talkin’, but you go on so’s anyone would think that——”

Here Ginger hurled himself upon William, and the two of them rolled on to the floor and wrestled among the faggots. Violent physical encounters were a regular part of the programme of the Outlaws’ meetings. Henry watched nonchalantly from his perch, crunching pear drops, occasionally throwing small twigs at them, and saying: “Go it!”—“That’s right!”—“Go it!” Joan watched with anxious horror, and “William, do be careful,” and: “Oh, Ginger, darling, don’t hurt him.”

Finally the combatants rose, dusty and dishevelled, shook hands, and resumed their seats on the stacks of firewood.

“Now, if you’ll only let me speak——” began William.

“We will, William, darling,” said Joan. “Ginger won’t interrupt, will you, Ginger?”

Ginger, who had decidedly had the worst of the battle, was removing dust and twigs from his mouth. He gave a non-committal grunt.

“Well, you know the Sale of Work next week?” went on William. They groaned. It was a ceremony to which each of the company would be led, brushed and combed and dressed in gala clothes, in a proud parent’s wake.

“Well,” went on William. “You jus’ listen carefully. I got an idea.”

They leant forward eagerly. They had a touching faith in William’s ideas that no amount of bitter experiences seemed able to destroy.

*****

The day of the Sale of Work was warm and cloudless. William’s mother and sister worked there all the morning. A tent had been erected, and inside the tent were a few select stalls of flowers and vegetables. Outside on the grass were the other stalls. The opening ceremony was to be performed by a real live duke.

William absented himself for the greater part of the morning, returning in time for lunch, and meekly offering himself to be cleaned and dressed afterwards like the proverbial lamb for the slaughter.

“William,” said Mrs. Brown to her husband, “is being almost too good to be true. It’s such a comfort.”

“I’m glad you can take comfort in it,” said Mr. Brown. “From my knowledge of William, I prefer him when you know what tricks he’s up to.”

“Oh, I think you misjudge him,” said Mrs. Brown, whose trust in William was almost pathetic.

“Ethel and I can’t go to the opening, darling,” said Mrs. Brown at lunch. “I’m rather tired. So I suppose you’ll wait and go with us later.”

William smiled his painfully sweet smile.

“I might as well go early. I might be able to help someone,” he said shamelessly.

Half an hour later William set off alone to the Sale of Work. He wore his super-best clothes. His hair was brushed to a chastened, sleek smoothness. He wore kid gloves. His shoes shone like stars.

He walked briskly down to the Sale of Work. Already a gay throng had assembled there. Joan was there, looking like a piece of thistledown in fluffy white, with her mother. Ginger was there, stiff and immaculate, with his mother.

William, Ginger, and Henry joined forces and stood talking in low, conspiratorial voices, looking rather uncomfortable in their excessive cleanness. Joan looked at them wistfully but was kept close to the maternal side.

The real live duke arrived. He was tall and stooping, and looked very bored and aristocratic.

Everything was ready for the opening. It was to take place on the open space of grass at the back of the tent. The chairs for the committee and the chair for the duke were close to the tent. Then a space was railed off from the crowd—from the ordinary people.

At the other side of the tent the stalls were deserted. His Grace stood for a few minutes in the tent by one of the stalls talking to the vicar’s wife. Then he went out to open the Sale of Work. A few minutes after his Grace had departed, William might have been seen to emerge from beneath the stall, his cap gone, his hair deranged, his knees dusty, and join Ginger and Henry in the deserted space behind the tent.

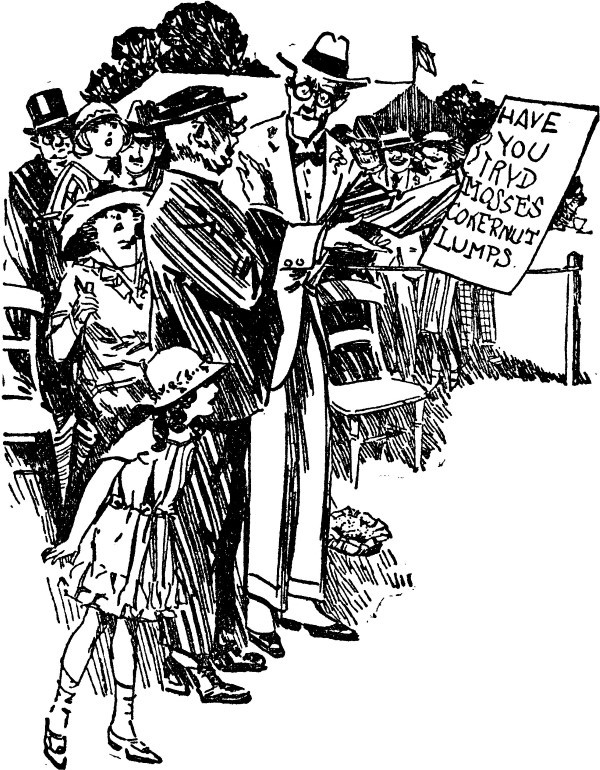

His Grace stood and uttered the few languid words that declared the Sale of Work open. But the committee who were a few yards behind him sat in open-mouthed astonishment. For a large placard adorned his Grace’s coat behind.

HAVE YOU TRYD

MOSSES

COKERNUT LUMPS?

The committee could think of no course of action with which to meet this crisis. They could only gasp with horror, open-eyed and open-mouthed.

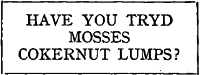

The few gracious words were said. The applause rose. His Grace turned round to converse pleasantly with the Vicar’s wife, exposing his back to the view of the crowd. The applause wavered, then redoubled ecstatically.

“Some kind of an advertising job,” said the organist’s wife.

But the crowd did not mind what it was. They held their sides. They clung to each other in helpless mirth. They followed that tall, slim, elegant figure with its incongruous placard as it went with the vicar’s wife round the tent to the stalls. The vicar’s wife talked nervously, and hysterically. “My dear, I couldn’t,” she said afterwards. “I didn’t know how to put it. I couldn’t think of words—and I kept thinking, suppose he knows and means it to be there. It somehow seemed better bred to ignore it.”

The committee clustered together in an anxious group.

“It wasn’t there when he came. Someone must have put it on.”

“My dear, someone must tell him.”

“Or creep up and take it off when he isn’t looking.”

“My dear—one couldn’t. Suppose he turned round when one was doing it, and thought one was putting it on!”

HIS GRACE EXAMINED THE PLACARD, THEN TURNED

TO THE VICAR. “HOW LONG EXACTLY,” HE SAID

SLOWLY, “HAVE I BEEN WEARING THIS?”

“The vicar must tell him—let’s find the vicar. I think it would come better from a clergyman, don’t you?”

“Yes, and he might—well, he couldn’t say much before a clergyman, could he?”

“And a vicar is so practised in consolation. I think you’re right—— But who did it?”

Flustered, panting, distraught, they hastened off in search of the vicar.

*****

Meanwhile, his Grace talked to the vicar’s wife. He was beginning to think that she was not quite herself. Her manner seemed more than peculiar. He glanced round. The stalls were still deserted.

“They haven’t begun to buy much yet, have they?” he said. “I suppose I must set the example.”

AT THAT MOMENT, WILLIAM,

GINGER AND HENRY EMERGED FROM

BENEATH ONE OF THE STALLS.

He wandered over to a stall and bought a pink cushion. Then he looked around again, his cushion under his arm, his placard still adorning the back of his coat. The crowd were engaged only in staring at him; they were fighting to get a glimpse of him; they were following him about like dogs——

“I suppose some of these people must know my name,” he said. “I thought that speech of mine in the House last week would wake people up——”

“Er—Oh, yes,” said the vicar’s wife. She blinked and swallowed. “Er—Oh, yes—indeed, yes—indeed, yes—I quite agree—er—quite!”

Here the vicar rescued her.

The vicar had not quite made up his mind whether to be jocular or condoling.

“A splendid attendance, isn’t it, your Grace? There’s a little thing I want to——” The vicar’s wife tactfully glided away. “Of course, we all understand—you’re not responsible—and, on our honour, we aren’t—quite an accident—the guilty party, however, shall be found. I assure you he shall—er—shall be found.”

“Would you mind,” said his Grace patiently, “telling me of what you are talking?”

The vicar drew a deep breath, then took the plunge.

“There’s a small placard on your back,” he said. “Well, not small—that is—allow me——”

His Grace hastily felt behind, secured the placard, tore it off, put on his tortoise-shell spectacles, and examined it at arm’s length. Then he turned to the vicar, who was mopping his brow. The committee were trembling in the background. One of them—Miss Spence by name—had already succumbed to a nervous breakdown and had had to go home. Another was having hysterics in the tent.

“How long exactly,” asked his Grace slowly, “have I been wearing this?”

The vicar smiled mirthlessly, and put up a hand nervously as if to loosen his collar.

“Er—quite a matter of minutes—ahem—of minutes one might say, your Grace, since—ah—ahem—since the opening, one might almost put it——”

“Then,” said his Grace, “why the devil didn’t you tell me before?”

The vicar put up his hand and coughed reproachfully.

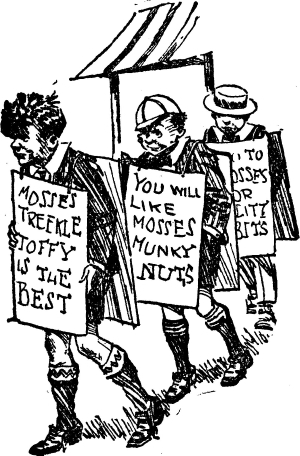

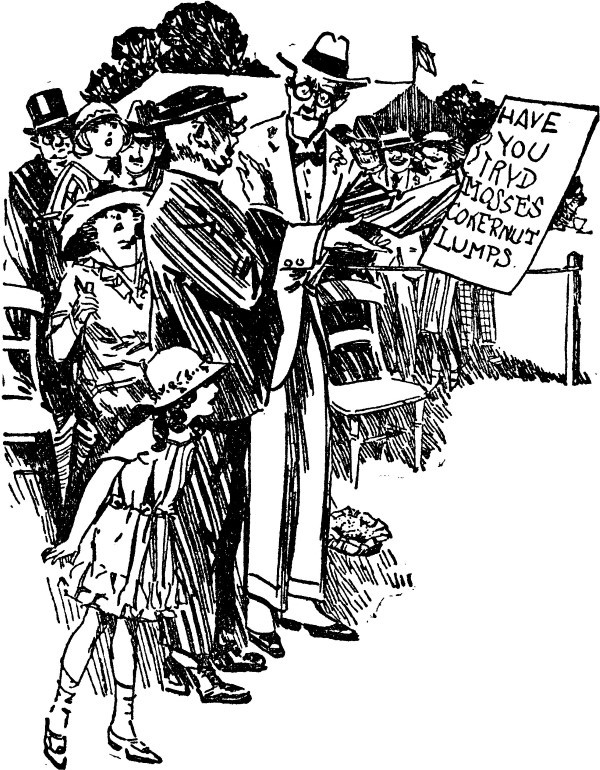

At this moment William, Ginger and Henry emerged from beneath one of the stalls, in whose butter-muslined shelter they had been preparing themselves, and awaiting the most dramatic moment to appear.

They all wore “sandwiches” made from sheets of cardboard and joined over their shoulders by string.

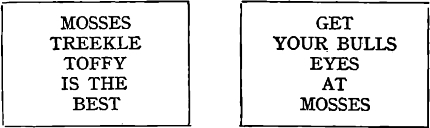

William bore before him— —and behind him

MOSSES TREEKLE TOFFY IS THE BEST GET YOUR BULLS EYES AT MOSSES

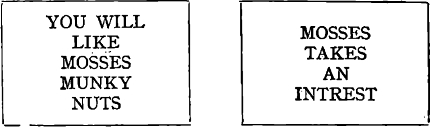

Ginger bore before him— —and behind him

YOU WILL LIKE MOSSES MUNKY NUTS MOSSES TAKES AN INTEREST

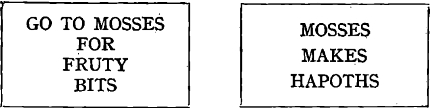

Henry bore before him— —and behind him

GO TO MOSSES FOR FRUTY BITS MOSSES MAKES HAPOTHS

Solemnly, with expressionless faces and eyes fixed in front of them, they paraded through the crowd. His Grace, who had taken off his spectacles, put them on again. His Grace was a good judge of faces.

“Secure that first boy,” he said.

The vicar, nothing loth, secured William by the collar and brought him before his Grace. His Grace held out his placard.

“Did you—er—attach this to my coat?” he asked sternly.

William shook off the vicar’s hand.

“Yes,” he said, as sternly as his Grace. “You see, we wanted people to go to Mr. Moss’ shop—’cause, you see, Mallards’ is a big company, an’ he’s not, an’ they’ve got—er—capitols behind them and he’s not—see? And we wanted to make people go to Moss’, and we thought we’d fix up notices wot’d make people go to Moss’ like big shops do—an’ we knew no one’d take any notice of our notices if we jus’ put ’em up anywhere, but we thought if we fixed one on to someone important wot everyone’d be lookin’ at all the time—an’ he’s awful kind an’ he takes an’ int’rest an’ he cares wot you get an’ his cokernut lumps is better’n anyone’s, an’ he makes ha’p’oths without makin’ a fuss—an’ he’s awful worried, an’ we wanted to help him——”

“An’ she’s a murderer,” piped Ginger.

Before his Grace could reply Joan wrenched herself free from her mother’s restraining hand and flew up to the group.

“Oh, please don’t do anything to William,” she pleaded. “It was my fault, too—I’m not a real one, but I’m an ally—till death do us part, you know.”

His Grace looked from one to the other. He had been bored almost to tears by the vicar’s wife and the committee. With a lightening of the heart he recognised more entertaining company.

“Well,” he said judicially, “come to the refreshment tent and we’ll talk it over, over an ice.”

*****

The news that his Grace had spent almost the entire afternoon eating ices with William Brown and those other children, discussing pirates and Red Indians, and telling them stories of big game hunting, made the village gasp.

The further knowledge that he had asked them to walk down to the station with him, had called at Moss’, tasted cokernut lumps, pronounced them delicious, bought a pound for each of them, and ordered a monthly supply, left the village almost paralysed. But everyone went to Mr. Moss’ to ask for details. Mr. Moss was known as the confectioner who supplied the Duke of Ashbridge with cokernut lumps. Mallards’ shop was let to a baker’s the next month, and the red-haired girl said that she wasn’t sorry—of all the dead-and-alive holes to work in this place was the deadest.

It was Miss Spence who voiced the prevailing sentiment about William. She did not say it out of affection for William. She had no affection for William.

William chased her cat and her hens, disturbed her rest with his unearthly songs and whistles, broke her windows with his cricket ball, and threw stones over the hedge into her garden pond.

But one day, as she watched William progress along the ditch—William never walked on the road if he could walk in the ditch—dragging his toes in the mud, his hands in his pockets, his head poking forward, his brows frowning, his freckled face stern and determined, his mouth pucked up to make his devastating whistle, his train of boy followers behind him, she said slowly: “There’s something about that boy——”