CHAPTER X

WILLIAM THE SHOWMAN

WILLIAM and his friends, known to themselves as the Outlaws, were in their usual state of insolvency. All entreaties had failed to melt the heart of Mr. Beezum, the keeper of the general stores in the village, who sold marbles, along with such goods as hams and shoes and vegetables.

William and his friends wanted marbles—simply a few dozen of ordinary glass marbles which could be bought for a few pence. But Mr. Beezum refused to overlook the small matter of the few pence. He refused to give the Outlaws credit.

“My terms to you, young gents, is cash down, an’ well you know it,” he said firmly.

“If you,” said William generously, “let us have the marbles now we’ll give you a halfpenny extra Saturday.”

“You said that once before, young gent, if I remember right,” said Mr. Beezum, adjusting his capacious apron and turning up his shirt-sleeves preparatory to sweeping out his shop.

William was indignant at the suggestion.

“Well,” he said, “well—you talk ’s if that was my fault—’s if I knew my people was going to decide sudden not to give me any money that week simply because one of their cucumber frames got broke by my ball. An’ I brought back the things wot you’d let me have. I brought the trumpet back an the rock——”

“Yes—the trumpet all broke an’ the rock all bit,” said Mr. Beezum. “No—cash down is my terms, an’ I sticks to ’em—if you please, young gents.”

He began his sweeping operations with great energy, and the Outlaws found themselves precipitated into the street by the end of his long broom.

“Mean,” commented William, rising again to the perpendicular. “Jus’ mean! I’ve a good mind not to buy ’em there at all.”

“He’s the only shop that sells ’em,” remarked Ginger.

“An’ we’ve got no money to buy ’em anywhere, anyway,” said Henry.

“S’pose we couldn’t wait for ’em till Saturday?” suggested Douglas tentatively.

He was promptly crushed by the Outlaws.

“Wait!” said Ginger. “Wait! Wot’s the use of waitin’? We may be doing something else on Saturday. We mayn’t want to play with marbles—all that long time off.”

“’F only you’d save your money,” said William severely, “’stead of spendin’ it the day you get it we shun’t be like this—no marbles, an’ swep’ out of his shop an’ nothing to play at.”

This was felt to be unfair.

“Well, I like that—I like that,” said Ginger. “And wot about you—wot about you?”

“Well, if I was the only one, you could have lent me money an’ we could get marbles with it—if you’d not spent all your money we could be buyin’ marbles now ’stead of standin’ swep’ out of his shop.”

Ginger thought over this, aware that there was usually some fallacy in William’s arguments if only one could lay one’s hand on it.

Henry turned away.

“Oh, come along,” he said impatiently. “It’s no good staring in at his ole butter an’ cheese. Let’s think of something else to do.”

“Anyway, it’s nasty cheese,” said Douglas comfortingly. “My mother said it was—so p’raps it’s a good thing we’ve been saved buyin’ his marbles.”

“Something else to do?” said William. “We want to play marbles, don’t we? Wot’s the good of thinkin’ of other things when we want to play marbles?”

“’S all very well to talk like that,” said Ginger with sudden inspiration. “An’ we might jus’ as well say that ’f you’d not spent your money you could have lent us some, an’ that’s just as much sense as you saying if we——”

“Oh, do shut up talkin’ stuff no one can understand,” said William, “let’s get some money.”

“How?” said Ginger, who was nettled. “All right. Get some, an’ we’ll watch you. You goin’ to steal some or make some. ’F you’re clever enough to steal some or make some I’ll be very glad to join with it.”

“Yes, well, if I stealed some or made some you just wouldn’t join with it,” said William crushingly.

“Let’s sell something,” said Henry.

“We’ve got nothing anyone’d buy,” said Ginger.

“Let’s sell Jumble.”

“Jumble’s mine. You can jus’ sell your own dogs,” said William, sternly.

“We’ve not got any.”

“Well, then, sell ’em.”

“That’s sense, isn’t it?” said Ginger. “Jus’ kindly tell us how to sell dogs we’ve not got—— Jus’——”

But William was suddenly tired of this type of verbal warfare.

“Let’s do something—let’s have a show.”

“Wot of?” said Ginger without enthusiasm. “We’ve got nothing to show, an’ who’ll pay us money to look at nothing. Jus’ tell us that.”

“We’ll get something to show—I know,” he said suddenly, “a c’lection of insecks. Anyone’d pay to see an exhibition of a c’lection of insecks, wun’t they? I don’t s’pose there are many c’lections of insecks, anyway. It’d be interestin’. Everyone’s interested in insecks.”

For a minute the Outlaws wavered.

“Who’d c’lect ’em?” said Henry, dubiously.

“I would,” said William with an air of stern purpose.

*****

The Collection of Insects was almost complete. The show was to be held that afternoon.

The audience had been ordered to attend and bring their halfpennies. The audience had agreed, but had reserved to itself the right not to contribute the halfpennies if the exhibition was not considered worth it.

“Well,” was William’s bitter comment on hearing this, “I shouldn’t have thought there was so many mean people in the world.”

He had taken a great deal of trouble with his collection. He had that very morning been driven out of Miss Euphemia Barney’s garden by Miss Euphemia herself, though he had only entered in pursuit of a yellow butterfly that he felt was indispensable to the collection.

Miss Euphemia Barney was the local poetess and the leader of the intellectual life of the village. Miss Euphemia Barney was the President of the Society for the Encouragement of Higher Thought. The members of the society discussed Higher Thought in all its branches once every fortnight. At the end of the discussion Miss Euphemia Barney would read her poems.

Euphemia Barney’s poems had never been published. Miss Euphemia said that in these days of worldliness and money-worship she would set an example of unworldliness and scorn for money. “I think it best,” she would say, “that I should not publish.”

As a matter of fact she had the authority of several publishers for the statement. She disliked William more than anyone else she had ever known—and she said that she knew just what sort of a woman Miss Fairlow was as soon as she heard that Miss Fairlow had “taken to” William.

Miss Fairlow had only recently come to live at the village. Miss Fairlow was a real, live, worldly, money-worshipping author who published a book every year and made a lot of money out of it. When she came to live in the village Miss Euphemia Barney was prepared to patronise her in spite of this fact, and even asked her to join the Society for the Encouragement of Higher Thought.

But, to the surprise of Miss Euphemia, Miss Fairlow refused.

Miss Euphemia pitied her as she would have pitied anyone who had refused the golden chance of belonging to the Society for the Encouragement of Higher Thought under her—Miss Euphemia Barney’s—presidency, but, as she said to the Society, “her influence would not have tended to the unworldliness and purity that distinguishes us from so many other societies and bodies—it is all for the best.”

To her most intimate friends she said that Miss Fairlow had refused the offer of membership in order to mask her complete ignorance of Higher Thought. “Ignorant, my dear,” she said. “Ignorant—like all these popular writers.”

So the Society for the Encouragement of Higher Thought pursued its pure and unworldly path, and Miss Fairlow only laughed at it from a distance.

*****

Chased ignominiously from Miss Euphemia’s garden, William went along to Miss Fairlow’s. He could see her over the hedge mowing the lawn.

“Hello,” he said.

“Hallo, William,” she replied.

“Got any insects there?” said William.

“Heaps. Come in and see.”

William came in with a business-like air—his large cardboard box under his arm—and began to hunt among her garden plants.

“Would you call a tortoise an insect?” he said suddenly.

“If I wanted to,” she replied.

“Well, I’m going to,” said William firmly. “And I’m going to call a white rat an insect.”

“I don’t see why you shouldn’t—it might belong to a special branch of the insect world, a very special branch. You ought to give it a very special name.”

The idea appealed to William.

“All right. What name?”

Miss Fairlow rested against the handle of her lawn mower in an attitude of profound meditation.

“We must consider that—something nice and long.”

“Omshafu,” said William suddenly, after a moment’s thought. “It just came,” he went on modestly, “just came into my head.”

“It’s a beautiful word,” said Miss Fairlow. “I don’t think you could have a better one—an insect of the Omshafu branch.”

“I think I’ll call its name Omshafu, too,” said William, picking a furry caterpillar off a leaf.

“Yes,” said Miss Fairlow, “it seems a pity not to use a word like that as much as you can now you’ve thought of it.”

William put a ladybird in on top of the caterpillar.

“It’s going to be jolly fine,” he said optimistically.

“What?” said Miss Fairlow.

“Oh, jus’ a c’lection of insects I’m doing,” said William.

Later in the morning, William brought Omshafu over to visit Miss Fairlow. It escaped, and Miss Fairlow pursued it up her front stairs and down her back ones, and finally captured it. Omshafu rewarded her by biting her finger. William was apologetic.

“I daresay it just didn’t like the look of me,” said Miss Fairlow sadly.

“Oh, no,” William hastened to reassure her; “it’s bit heaps of people this year—it bites people it likes. I don’t see why it shun’t be an insect, anyway, do you?”

*****

William’s Collection of Insects was ready for the afternoon’s show. The exhibits were arranged in small cardboard boxes, covered mostly with paper, and these were all packed into a large cardboard box.

The only difficulty was that he could not think where to conceal it from curious or disapproving eyes till after lunch. The garden, he felt, was not safe—cats might upset it, and once upset in the garden the insects would be able to return to their native haunts too quickly. His mother would not allow him to keep them indoors. She would find them and expel them wherever he put them.

Unless—William had a brilliant idea—he hid them under the drawing-room sofa. The drawing-room sofa had a cretonne cover with a frill that reached to the floor, and he had used this place before as a temporary receptacle for secret treasures. No one would look under it, or think of his putting anything there. He put the tortoise into a box with a lid, and tied Omshafu up firmly with string in his box, and put them in the large cardboard box with the insects. Then he put the large cardboard box under the sofa and went into lunch with a mind freed from anxiety.

The exhibition was not to begin till three, so William wandered out to find Jumble. He found him in the ditch, threw sticks for him, brushed him severely with an old boot brush that he kept in the outhouse for the rare occasions of Jumble’s toilet, and finally tied round his neck the old, raggy and almost colourless pink ribbon that was his gala attire. Then he came to the drawing-room for the exhibits. There he received his first shock.

On the drawing-room sofa sat Miss Euphemia Barney, wearing her very highest thought expression. She surveyed William from head to foot silently with a look of slight disgust, then turned away her head with a shudder. William sought his mother.

“Wot’s she doin’ in our house?” he demanded sternly.

“I’ve lent the drawing-room for a meeting of the Higher Thought, darling,” said Mrs. Brown reverently, “because she has the painters in her own drawing-room. You mustn’t interrupt.”

Mrs. Brown was not a Higher Thinker, but she cherished a deep respect for them.

“But——” began William indignantly, then stopped. He thought, upon deliberation, that it was better not to betray his hiding-place.

He went back to the drawing-room determined to walk boldly up to the sofa and drag out the exhibits from under the very skirts of Miss Euphemia Barney. But two more Higher Thinkers were now established upon the sofa, one on each side of the President, and Higher Thinkers were pouring into the room. William’s courage failed him. He sat down upon a chair by the door scowling, his eyes fixed upon Miss Euphemia’s skirts.

The members looked at him with lofty disapproval. The gathering was complete. The meeting was about to begin. Miss Euphemia Barney was to speak on the Commoner Complexes. But first she turned upon William, who sat with his eyes fixed forlornly on the hem of her skirts, a devastating glare.

“Do you want anything, little boy?” she said.

Before William had time to tell her what he wanted the maid threw open the door and announced Miss Fairlow. The Higher Thinkers gasped. Miss Fairlow looked round as Daniel must have looked round at his lions.

“I came——” she said. “Oh, dear!”

Miss Euphemia waved her to a seat. It occurred to her that here was a heaven-sent opportunity of impressing Miss Fairlow with a real respect for Higher Thought. Miss Fairlow must learn how much higher they were in thought than she could ever be. It would be a great triumph to enlist Miss Fairlow as a humble member and searcher after truth under her—Miss Euphemia’s—leadership.

“You came to see Mrs. Brown, of course,” she said kindly, “and the maid showed you in here thinking you were—ahem—one of us. Mrs. Brown has kindly lent us her drawing-room for a meeting. Pray don’t apologise—perhaps you would like to listen to us for a short time. We were about to discuss the Commoner Complexes. I will begin by reading a little poem. I spent most of this morning putting the final touches to it,” she ended proudly.

“I spent most of this morning on the pursuit of Omshafu,” said Miss Fairlow gravely.

There was a moment’s tense silence. Omshafu? The Higher Thinkers sent glances of desperate appeal to their president. Would she allow them to be humiliated by this upstart?

“Ah, Omshafu!” said Miss Euphemia slowly. “Of course it—it is very interesting.”

The Higher Thinkers gave a sigh of relief.

“I could hardly tear myself away this morning,” replied Miss Fairlow pleasantly. “It was so engrossing.”

Engrossing! Some sort of Eastern philosophy, of course. Again desperate glances were turned upon the embodiment of Higher Thought. Again she rose to the occasion.

“I felt just the same about it when I—er—when I,” she risked the expression, “took it up.”

She felt that this implied that she had known about Omshafu long before Miss Fairlow, and this conveyed a delicate snub.

Miss Fairlow’s glance rested momentarily on her bandaged finger.

“THERE’S OMSHAFU HIMSELF,” SAID MISS FAIRLOW

IN HER CLEAR VOICE. “I CAN SEE HIS DEAR LITTLE

PINK NOSE PEEPING OUT.”

“It goes very deep,” she murmured.

Miss Barney was gaining confidence.

“There I disagree with you,” she said firmly. “I think its appeal is entirely superficial.”

William had brightened into attention at the first mention of Omshafu, but finding the conversation beyond him, had relapsed into a gloomy stare. Now his state became suddenly fixed; his mouth opened with horror.

MISS EUPHEMIA JUMPED UP WITH A PIERCING SCREAM.

“SOMETHING STUNG ME!” SHE CRIED. “IT’S BEES

COMING FROM UNDER THE SOFA!”

The exhibits were escaping from beneath the hem of Miss Euphemia’s gown. A cockroach was making a slow and stately progress into the middle of the room, several ants were laboriously climbing up Miss Euphemia’s dress. So far no one else had noticed. William gazed in frozen horror.

“I hear that Omshafu has bitten most people this year,” said Miss Fairlow demurely.

Miss Euphemia pursued her lips disapprovingly. She was growing reckless with success. “I think there’s something dangerous in it,” she said.

“You mean its teeth?” said Miss Fairlow brightly.

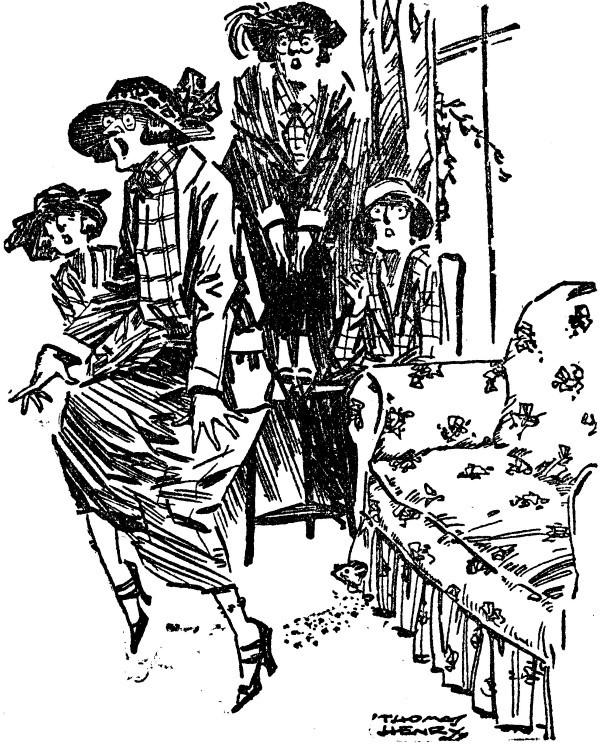

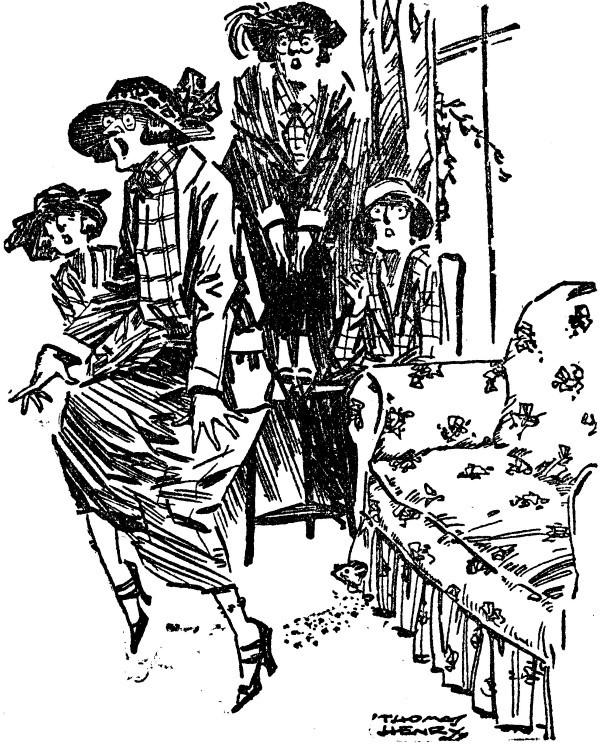

There was a moment’s tense silence. A horrible suspicion occurred to Miss Euphemia that she was being trifled with. The Higher Thinkers looked helplessly first at her and then at Miss Fairlow. Then Miss Euphemia rose from the sofa with a piercing scream.

“Something’s stung me! It’s bees—bees coming from under the sofa!”

Simultaneously the Treasurer jumped upon a small occasional table.

“Black beetles!” she screamed. “Help!”

Above the babel rose Miss Fairlow’s clear voice.

“And there’s Omshafu himself. I can see his dear little pink nose peeping out.”

Babel ceased for one second while the Society for the Encouragement of Higher Thought looked at Omshafu. Then it arose with redoubled violence.

*****

William departed with his exhibits. He had recaptured most of them. Omshafu had been taken from the ample silk sash of the Treasurer in a fold of which he had taken refuge. William had left his mother and Miss Fairlow pouring water on the hysterical Treasurer.

William was late as it was. Behind him trotted Jumble, the chewed-up remains of his gala attire hanging from his mouth.

“William.”

Miss Fairlow was just behind, carrying a cardboard box.

“Oh, William,” she said, “I was really bringing this to you when they showed me into the wrong room and I couldn’t resist having a game with them. I found it this morning after you’d gone—in an old drawer I was tidying, and I thought you might like it.”

William opened it. It was a case of butterflies—butterflies of every kind, all neatly labelled.

“I think it used to belong to my brother,” said Miss Fairlow carelessly. “Would you like it?”

“Oh, crumbs!” gasped William. “Thanks.”

“And I’ve had the loveliest time this afternoon that I’ve had for ages,” said Miss Fairlow dreamily. “Thank you so much.”

William hastened to the old barn in which the Exhibition was to be held. Ginger, Douglas and Henry and the audience were already there.

“Well, you’re early, aren’t you?” said Douglas sarcastically.

“D’you think,” said William sternly, “that anyone wot has had all the hard work I’ve had getting together this c’lection could be here earlier?”

The half-dozen little boys who formed the audience grasped their halfpennies firmly and looked at William suspiciously.

“They won’t give up their halfpennies,” said Henry in deep disgust.

“No,” said the audience, “not till we’ve seen if it’s worth a halfpenny.”

William assumed his best showman air.

“This, ladies and gentlemen,” he began, ignoring the fact that his audience consisted entirely of males, “is the only tortoise like this in the world.”

“Seen a tortoise.” “Got a tortoise at home,” said his audience unimpressed.

“Perhaps,” said William crushingly. “But have you ever seen a tortoise with white stripes like wot this one has?”

“No, but I could if I got an ole tin of paint and striped our one.”

William passed on to the next box.

He took out Omshafu.

“This,” he said, “is the only rat inseck of the speeshees of Omshafu——”

“If you think,” said the audience, “that we’re goin’ to pay a halfpenny to see that ole rat wot we’ve seen hundreds of times before, and wot’s bit us, too—well, we’re not.”

Despair began to settle down upon Ginger’s face.

William passed on to the third box.

“Here, ladies and gentlemen,” he said impressively, “is thirty sep’rate an’ distinct speeshees of insecks. I only ask you to look at them. I——”

“They’re jus’ the same sort of insecks as crawl about our garden at home,” said the audience coldly.

“But have you ever seen ’em c’lected together before?” said William earnestly. “Have you ever seen ’em c’lected? Think of the trouble an’ time wot I took c’lecting ’em. Why, the time alone I took’s worth more’n a halfpenny. I should think that’s worth a halfpenny. I should think it’s worth more’n a halfpenny. I should think——”

“Well, we wun’t,” said the audience. “We’d as soon see ’em crawling about a garden for nothin’ as crawlin’ about a box for a halfpenny. So there.”

Ginger, Douglas and Henry looked at William gloomily.

“They aren’t worth getting a c’lection for,” said Ginger.

“They deserve to have their halfpennies took off ’em!” said Douglas.

But William slowly and majestically brought out his fourth box and opened it, revealing rows of gorgeous butterflies, then closed it quickly.

The audience gasped.

“When you’ve given in your halfpennies,” said William firmly, “then you can see this wonderfu’ an’ unique c’lection of twenty sep’rate an’ distinct speeshees of butterflies all c’lected together.”

Eagerly the halfpennies were given to William. He handed them to Douglas, triumphantly. “Go an’ buy the marbles, quick,” he said in a hoarse whisper, “case they want ’em back.”

Then he turned to his audience, smoothed back his hair, and reassumed his showman manner.

*****

In Mrs. Brown’s drawing-room the members of the Society for the Encouragement of Higher Thought were recovering from various stages of hysterics.

“We shall have to dissolve the society,” said Miss Euphemia Barney. “She’ll tell everyone. It’s a wicked name for a rat, anyway—almost blasphemous—I’m sure it comes in the Bible. How was one to know? But people will never forget it.”

“We might form ourselves again a little later under a different name,” suggested the Secretary.

“People will always remember,” said Miss Euphemia. “They’re so uncharitable. It’s a most unfortunate occurrence. And,” setting her lips grimly, “as is the case with most of the unfortunate occurrences in this village, the direct cause is that terrible boy, William Brown.”

At that moment the direct cause of most of the unfortunate occurrences in the village, with his friends around him, his precious box of butterflies by his side, and happiness in his heart, was just beginning the hard-won, long-deferred game of marbles.