CHAPTER XII

WILLIAM ENTERS POLITICS

WHEN William at the Charity Fair was asked to join a sixpenny raffle for a picture, and shown the prize—a dingy oil painting in an oval gilt frame, his expression registered outrage and disgust.

It was only when his friend Ginger whispered excitedly: “I say, William, las’ week my aunt read in the paper about someone what scraped off an ole picture like that an’ found a real valuable ole master paintin’ underneath an’ sold it for more’n a thousand pounds,” that he hesitated. An inscrutable expression came upon his freckled face as he stared at the vague head and shoulders of a lightly clad female against a background of vague trees and elaborate columns.

“All right,” he said, suddenly holding out the sixpence that represented his sole worldly assets, and receiving Ticket number 33.

“Don’t forget it was me what suggested it,” said Ginger.

“Yes, an’ don’t forget it was my sixpence,” said William sternly.

William was not usually lucky, but on this occasion the number 33 was drawn, and William, purple with embarrassment, bore off his gloomy-looking trophy. Accompanied by Ginger he took it to the old barn.

They scraped off the head and shoulders of the mournful and inadequately clothed female, and they scraped off the gloomy trees, and they scraped off the elaborate columns. To their surprise and indignation no priceless old master stood revealed. Being thorough in all they did, they finally scraped away the entire canvas and the back.

“Well,” said William, raising himself sternly from the task when nothing scrapable seemed to remain, “an’ will you kin’ly tell me where this valu’ble ole master is?”

“Who said definite there was a valu’ble ole master?” said Ginger in explanation. “’F you kin’ly remember right p’raps you’ll kin’ly remember that I said that an aunt of mine said that she saw in the paper that someone’d scraped away an ole picture an’ found a valu’ble ole master. I never said——”

William was arranging the empty oval frame round his neck.

“P’raps now,” he interrupted ironically, “you’d like to start scratchin’ away the frame, case you find a valu’ble ole master frame underneath.”

“Will it hoop?” said Ginger with interest, dropping hostilities for the moment.

They tried to “hoop” it, but found that it was too oval. William tried to wear it as a shield but it would not fit his arm. They tried to make a harp of it by nailing strands of wire across it, but gave up the attempt when William had cut his finger and Ginger had hammered his thumb three times.

William carried it about with him, his disappointment slightly assuaged by the pride of possession, but its size and shape were hampering to a boy of William’s active habits, so in the end he carefully hid it behind the door of the old barn which he and his friends generally made their headquarters, and then completely forgot it.

*****

The village was agog with the excitement of the election. The village did not have a Member of Parliament all to itself—it joined with the neighbouring country town—but one of the two candidates, Mr. Cheytor, the Conservative, lived in the village, so feeling ran high.

William’s father took no interest in politics, but William’s uncle did.

William’s uncle supported the Liberal candidate, Mr. Morrisse. He threw himself whole-heartedly into the cause. He distributed bills, he harangued complete strangers, he addressed imaginary audiences as he walked along the road, he frequently brought one hand down heavily upon the other with the mystic words: “Gentlemen, in the sacred cause of Liberalism——”

William was tremendously interested in him. He listened enraptured to his monologues, quite unabashed by his uncle’s irritable refusals to explain them to him. Politically the uncle took no interest in William. William had no vote.

William’s uncle was busily preparing to hold a meeting of canvassers for the cause of the great Mr. Morrisse in his dining-room. Mr. Morrisse, a tall, thin gentleman, for some obscure reason very proud of his name, who went through life saying plaintively, “double S E, please,” was not going to be there. William’s uncle was going to tell the canvassers the main features of the programme with which to dazzle the electors of the neighbourhood.

“I s’pose,” said William carelessly, “you don’t mind me comin’?”

“You suppose wrong then,” said William’s uncle. “I most emphatically mind your coming.”

“But why?” said William earnestly. “I’m int’rested. I’d like to go canvassing too. I know a lot ’bout the rackshunaries—you know, the ole Conservies—I’d like to go callin’ ’em names, too. I’d like——”

“You may not attend the Liberal canvassers’ meeting, William,” said William’s uncle firmly.

From that moment William’s sole aim in life was to attend the Liberal canvassers’ meeting. He and Ginger discussed ways and means. They made an honest and determined effort to impart to William an adult appearance, making a frown with burnt cork, and adding whiskers of matting which adhered to his cheeks by means of glue. Optimists though they were, they were both agreed that the chances of William’s admittance, thus disguised, into the meeting of the Liberal canvassers was but a faint one.

So William evolved another plan.

*****

The dining-room in which William’s uncle was to hold his meeting was an old-fashioned room. A hatch, never used, opened from it on to an old stone passage.

The meeting began.

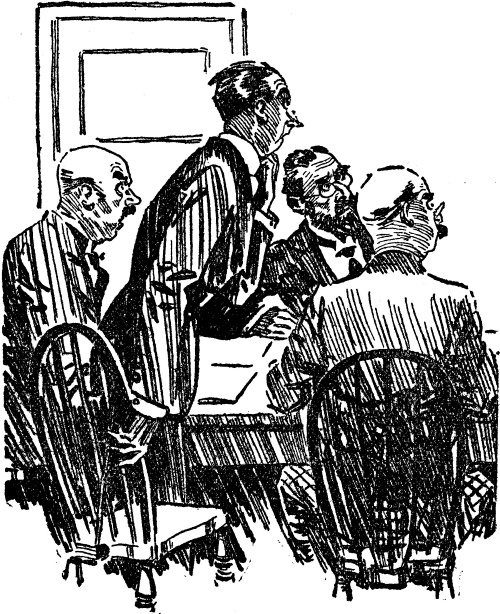

William’s uncle arrived and took his seat at the head of the table with his back to the hatch. William’s uncle was rather short-sighted and rather deaf. The other Liberal canvassers filed in and took their places round the table.

William’s uncle bent over his papers. The other Liberal canvassers were gazing with widening eyes at the wall behind William’s uncle. The hatch slowly opened. A dirty oval gilt frame appeared, and was by no means soundlessly attached to the top of the open hatch. Through the aperture of the frame appeared a snub-nosed, freckled, rough-haired boy with a dirty face and a forbidding expression.

William didn’t read sensational fiction for nothing. In “The Sign of Death,” which he had finished by the light of a candle at 11.30 the previous evening, Rupert the Sinister, the international spy, had watched a meeting of masked secret service agents by the means of concealing himself in a hidden chamber in the wall, cutting out the eye of a portrait and applying his own eye to the hole. William had determined to make the best of slightly less favourable circumstances.

There was no hidden chamber, but there was a hatch; there was no portrait, but there was the useless frame for which William had bartered his precious sixpence. He still felt bitter at the thought.

William felt, not unreasonably, that the sudden appearance in the dining-room of a new and mysterious portrait of a boy might cause his uncle to make closer investigations, so he waited till his uncle had taken his seat before he hung himself.

Ever optimistic, he thought that the other Liberal canvassers would be too busy arranging their places to notice his gradual and unobtrusive appearance in his frame. With vivid memories of the illustration in “The Sign of Death” he was firmly convinced that to the casual observer he looked like a portrait of a boy hanging on the wall.

In this he was entirely deceived. He looked merely what he was—a snub-nosed, freckled, rough-haired boy hanging up an old empty frame in the hatch and then crouching on the hatch and glaring morosely through the frame.

MR. MOFFAT MET WILLIAM’S STONY STARE. THE OTHER

HELPERS WERE STARING BLANKLY AT THE WALL.

“DON’T YOU THINK THAT POINT IS VERY IMPORTANT!”

ASKED WILLIAM’S UNCLE.

William’s uncle opened the meeting:

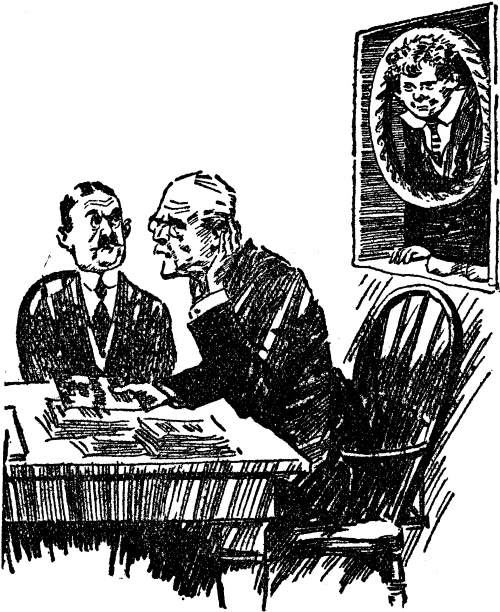

“... and we must emphasise the consequent drop in the price of bread. Don’t you think that point is very important, Mr. Moffat?”

Mr. Moffat, a thin, pale youth with a large nose and a naturally startled expression, answered as in a trance, his mouth open, his strained eyes fixed upon William.

“Er—very important.”

“Very—we can’t over-emphasise it,” said William’s uncle.

Mr. Moffat put up a trembling hand as if to loosen his collar. He wondered if the others saw it too.

“Over-emphasise it,” he repeated, in a trembling voice.

Then he met William’s stony stare and looked away hastily, drawing his handkerchief across his brow.

“I think we can safely say,” said William’s uncle, “that if the Government we desire is returned the average loaf will be three-halfpence cheaper.”

He looked round at his helpers. Not one was taking notes. Not one was making a suggestion. All were staring blankly at the wall behind him.

Extraordinary what stupid fellows seemed to take up this work—that chap with the large nose looked nothing more or less than tipsy!

“Here are some pamphlets that we should take round with us....”

He spread them out on the table. William was interested. He could not see them properly from where he was. He leant forward through his frame. He could just see the words, “Peace and Prosperity....” He leant forward further. He leant forward too far. Accidentally attaching his frame round his neck on his way he descended heavily from the hatch. There was only one thing to do to soften his fall. He did it. He clutched at his uncle’s neck as he descended. A confused medley consisting of William, his uncle, the frame and his uncle’s chair rolled to the floor where they continued to struggle wildly.

“Oh, my goodness,” squealed the young man with the large nose hysterically.

Somehow in the mêlée that ensued William managed to preserve his frame. He arrived home breathless and dishevelled but still carrying his frame. He was beginning to experience a feeling almost akin to affection for this companion in adversity.

“What’s the matter?” said William’s father sternly. “What have you been doing?”

“Me?” said William in a voice of astonishment. “Me?”

“Yes, you,” said his father. “You come in here like a tornado, half dressed, with your hair like a neglected lawn——”

William hastily smoothed back his halo of stubby hair and fastened his collar.

“Oh, that,” he said lightly. “I’ve only jus’ been out—walking an’ things.”

Mrs. Brown looked up from her darning.

“I think you’d better go and brush your hair and wash your face and put on a clean collar, William,” she suggested mildly.

“Yes, Mother,” agreed William without enthusiasm. “Father, did you know that the Libr’als are goin’ to make bread an’ everything cheaper an’—an’ prosperity an’ all that?”

“I did not,” said Mr. Brown dryly from behind his paper.

“I’d give it a good brushing,” said his wife.

“If there weren’t no ole rackshunary Conservy here,” said William, “I s’pose there wouldn’t be no reason why the Lib’ral shouldn’t get in?”

“As far as I can disentangle your negatives,” said Mr. Brown, “your supposition is correct.”

“I simply can’t think why it always stands up so straight,” said Mrs. Brown plaintively.

“Well, then, why don’t they stop ’em?” said William indignantly. “Why do they let the ole Conservies come in an’ spoil things an’ keep bread up—why don’t they stop ’em—why——”

Mr. Brown uttered a hollow groan.

“William,” said he grimly. “Go—and—brush—your—hair.”

“All right,” he said. “I’m jus’ goin’.”

*****

Mr. Cheytor, the Conservative candidate, had addressed a crowded meeting and was returning wearily to his home.

He opened the door with his latchkey and put out the hall light. The maids had gone to bed. Then he went upstairs to his bedroom. He opened the door. From behind the door rushed a small whirlwind. A rough bullet-like head charged him in the region of his abdomen. Mr. Cheytor sat down suddenly. A strange figure dressed in pyjamas, and over those a dressing-gown, and over that an overcoat, stood sternly in front of him.

“You’ve gotter stop it,” said an indignant voice. “You’ve gotter stop it an’ let the Lib’rals get in—you’ve gotter stop——”

Mr. Cheytor stood up and squared at William. William, who fancied himself as a boxer, flew to the attack. The Conservative candidate was evidently a boxer of no mean ability, but he lowered his form to suit William’s. He parried William’s wild onsets, he occasionally got a very gentle one in on William. They moved rapidly about the room, in a silence broken only by William’s snortings. Finally Mr. Cheytor fell over the hearthrug and William fell over Mr. Cheytor. They sat up on the floor in front of the fire and looked at each other.

“Now,” said Mr. Cheytor soothingly. “Let’s talk about it. What’s it all about?”

“They’re goin’ to make bread cheaper—the Lib’rals are,” panted William, “an’ you’re tryin’ to stoppem an’ you——”

“Ah,” said Mr. Cheytor, “but we’re going to make it cheaper, too.”

William gasped.

“You?” he said. “The Rackshunaries? But—if you’re both tryin’ to make bread cheaper why’re you fightin’ each other?”

“You know,” said Mr. Cheytor, “I wouldn’t bother about politics if I were you. They’re very confusing mentally. Suppose you tell me how you got here.”

“I got out of my window and climbed along our wall to the road,” said William simply, “and then I got on to your wall and climbed along it into your window.”

“Now you’re here,” said Mr. Cheytor, “we may as well celebrate. Do you like roasted chestnuts?”

“Um-m-m-m-m-m,” said William.

“Well, I’ve got a bag of chestnuts downstairs—we can roast them at the fire. I’ll get them. By the way, suppose your people find you’ve gone?”

“My uncle may’ve come to see my father by now, so I don’t mind not being at home jus’ now.”

Mr. Cheytor accepted this explanation.

“I’ll go down for the chestnuts then,” he said.

*****

Fortune was kind to William. His uncle was very busy and thought he would put off the laying of his complaint before William’s father till the next week. The next week he was still more busy. Encountering William unexpectedly in the street he was struck by William’s (hastily assumed) expression of wistful sadness, and decided that the whole thing may have been a misunderstanding. So the complaint was never laid.

Moreover, no one had discovered William’s absence from his bedroom. William came down to breakfast the next day with a distinct feeling of fear, but one glance at his preoccupied family relieved him. He sat down at his place with that air of meekness which in him always betrayed an uneasy conscience. His father looked up.

“Good morning, William,” he said. “Care to see the paper this morning? I suppose with your new zeal for politics——”

“Oh, politics!” said William contemptuously. “I’ve given ’em up. They’re so—so,” frowning he searched in his memory for the phrase, “They’re so—confusing ment’ly.”

His father looked at him.

“Your vocabulary is improving,” he said.

“You mean my hair?” said William with a gloomy smile. “Mother’s been scrubbin’ it back with water same as what she said.”

William walked along the village street with Ginger. Their progress was slow. They stopped in front of each shop window and subjected the contents to a long and careful scrutiny.

“There’s nothin’ there I’d buy ’f I’d got a thousand pounds.”

“Oh, isn’t there? Well, I jus’ wonder. How much ’ve you got, anyway?”

“Nothin’. How much have you?”

“Nothin’.”

“Well,” said William, continuing a discussion which their inspection of the General Stores had interrupted, “I’d rather be a Pirate than a Red Indian—sailin’ the seas an’ finding hidden treasure——”

“I don’t quite see,” said Ginger with heavy sarcasm, “what’s to prevent a Red Indian finding hidden treasure if there’s any to find.”

“Well,” said William heatedly, “you show me a single tale where a Red Indian finds a hidden treasure. That’s all I ask you to do. Jus’ show me a single tale where a——”

“We’re not talkin’ about tales. There’s things that happen outside tales. I suppose everything in the world that can happen isn’t in tales. ’Sides, think of the war-whoops. A Pirate’s not got a war-whoop.”

“Well, if you think——”

They stopped to examine the contents of the next shop window. It was a second-hand shop. In the window was a medley of old iron, old books, broken photograph frames and dirty china.

“An’ there’s nothin’ there I’d wanter buy if I’d got a thousand pounds,” said William sternly. “It makes me almost glad I’ve got no money. It mus’ be mad’ning to have a lot of money an’ never see anything in a shop window you’d want to buy.”

Suddenly Ginger pointed excitedly to a small card propped up in a corner of the window, “Objects purchased for Cash.”

“William,” gasped Ginger. “The frame!”

A look of set purpose came into William’s freckled face. “You stay here,” he whispered quickly, “an’ see they don’t take that card out of the window, an’ I’ll fetch the frame.”

Panting, he reappeared with the frame a few minutes later. Ginger’s presence had evidently prevented the disappearance of the card. An old man with a bald head and two pairs of spectacles examined the frame in silence, and in silence handed William half a crown. William and Ginger staggered out of the shop.

“Half a crown!” gasped William excitedly. “Crumbs!”

“I hope,” said Ginger, “you’ll remember who suggested you buying that frame.”

“An’ I hope,” said William, “that you’ll remember whose sixpence bought it.”

This verbal fencing was merely a form. It was a matter of course that William should share his half a crown with Ginger. The next shop was a pastry-cook’s. It was the type of pastry-cook’s that William’s mother would have designated as “common.” On a large dish in the middle of the window was a pile of sickly-looking yellow pastries full of sickly-looking yellow butter cream. William pressed his nose against the glass and his eyes widened.

“I say,” he said, “only a penny each. Come on in.”

They sat at a small marble-topped table, between them a heaped plate of the nightmare pastries, and ate in silent enjoyment. The plate slowly emptied. William ordered more. As he finished his sixth he looked up. His uncle was passing the window talking excitedly to Mr. Morrisse’s agent. Across the street a man was pasting up a poster, “Vote for Cheytor.” William regarded both with equal contempt. He took up his seventh penny horror and bit it rapturously.

“Fancy,” he said scornfully, “fancy people worryin’ about what bread costs.”