CHAPTER IV

WILLIAM ALL THE TIME

WILLIAM was walking down the road, his hands in his pockets, his mind wholly occupied with the Christmas pantomime. He was going to the Christmas pantomime next week. His thoughts dwelt on rapturous memories of previous Christmas pantomimes—of Puss in Boots, of Dick Whittington, of Red Riding Hood. His mouth curved into a blissful smile as he thought of the funny man—inimitable funny man with his red nose and enormous girth. How William had roared every time he appeared! With what joy he had listened to his uproarious songs! But it was not the funny man to whom William had given his heart. It was to the animals. It was to the cat in Puss in Boots, the robins in The Babes in the Wood, and the wolf in Red Riding Hood. He wanted to be an animal in a pantomime. He was quite willing to relinquish his beloved future career of pirate in favour of that of animal in a pantomime. He wondered....

It was at this point that Fate, who often had a special eye on William, performed one of her lightning tricks.

A man in shirt-sleeves stepped out of the wood and looked anxiously up and down the road. Then he took out his watch and muttered to himself. William stood still and stared at him with frank interest. Then the man began to stare at William, first as if he didn’t see him, and then as if he saw him.

“Would you like to be a bear for a bit?” he said.

William pinched himself. He seemed to be awake.

“A b-b-bear?” he queried, his eyes almost starting out of his head.

“Yes,” said the man irritably, “a bear. B.E.A.R. bear. Animal—Zoo. Never heard of a bear?”

William pinched himself again. He seemed to be still awake.

“Yes,” he agreed as though unwilling to commit himself entirely. “I’ve heard of a bear all right.”

“Come on, then,” said the man, looking once more at his watch, once more up the road, once more down the road, then turning on his heel and walking quickly into the wood.

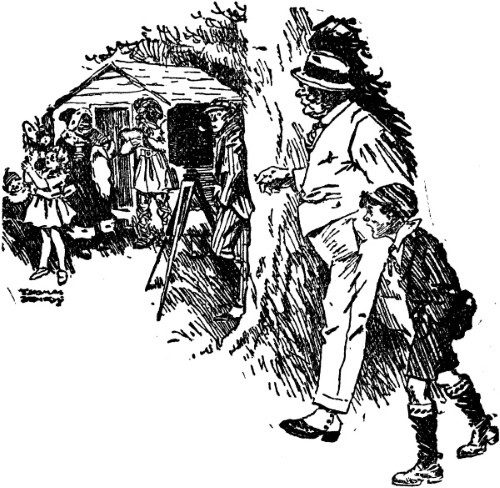

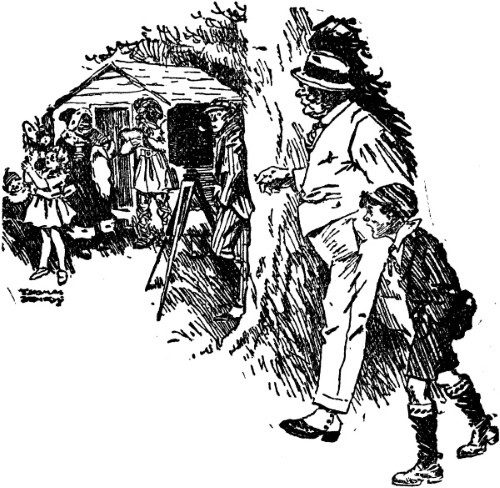

William followed, both mouth and eyes wide open. The man did not speak as he walked down the path. Then suddenly down a bend in the path they came upon a strange sight. There was a hut in a little clearing, and round the hut was clustered a group of curious people—a Father Christmas, holding his beard in one hand and a glass of ale in the other; a rather fat Goldilocks, in the act of having yellow powder lavishly applied to her face, several fairies and elves, sucking large and redolent peppermints; a ferocious, but depressed-looking giant, rubbing his hands together and complaining of the cold; and several other strange and incongruous figures. In front of the hut was a large species of camera with a handle, and behind stood a man smoking a pipe.

“Kid turned up?” he said.

William’s guide shook his head.

“No,” he said, “they’ve missed their train or lost their way, or evaporated, or got kidnapped or something, but this happened to be passing, and it looked the same size pretty near. What do you think?”

SUDDENLY DOWN A BEND IN THE PATH THEY CAME UPON

A STRANGE SIGHT.

The man took his pipe from his mouth in order the better to concentrate his whole attention on William. He looked at William from his muddy boots to his untidy head. Then he reversed the operation, and looked from his untidy head to his muddy boots. Then he scratched his head.

“Seems on the big side for the middle one,” he said.

At this point a hullabaloo arose from behind the shed, and a small bear appeared, howling loudly.

“He tooken my bit of toffee,” yelled the bear in a very human voice.

“Aw, shut up!” said the man in his shirt-sleeves.

The small bear was followed by a large bear, protesting loudly.

“I gave him half’n mine ’n’e promised to give me half’n his’ ’n’ then he tried to eat it all’n’——”

“Aw, shut up!” repeated the man. Then he turned to William.

“All you gotter do,” he said, “is to fix on the middle bear’s suit an’ do exactly what you’re told, an’ I’ll give you five shillings at the end. See?”

“These roural places are a butiful chinge,” murmured Goldilocks’ mother, darkening her eyebrows as she spoke. “So calm and quart.”

“These Christmas shows,” grumbled the giant, flapping his arms vigorously, “are the very devil.”

Here William found his voice. “Crumbs!” he ejaculated. Then, feeling the expletive to be altogether inadequate to the occasion, quickly added: “Gosh!”

“Take the kid round, someone,” said the shirt-sleeve man wearily, “and fix on his togs, and let’s get on with the show.”

Here a Fairy Queen appeared from behind the hut.

“I don’t see how I’m possibly to go through with this here performance,” she said in a voice of plaintive suffering. “I had toothache all last night——”

“If you think,” said the shirt-sleeve man, “that you can hold up this blessed show for a twopenny-halfpenny toothache——”

“If you’re going to be insulting——” said the Fairy Queen in shrill indignation.

“Aw, shut up!” said the shirt-sleeve man.

Here Father Christmas, who had finished his ale, led William into the hut. A bear’s suit lay on a chair.

“The kid wot was to wear this not having turned up,” he said by way of explanation, “and you by all accounts bein’ willin’ to oblige for a small consideration, we shall have to see what can be done. I suppose,” he added, “you have no objection?”

“Me?” said William, whose eyes and mouth had grown more and more circular every minute. “Me—objection? Golly! I should think not.”

The little bear and the big bear surveyed him critically.

“He’s too big,” said the little bear contemptuously.

“His hair’s too long,” contributed the big bear.

“His face is too dirty.”

“His ears is too long.”

“His nose is too flat.”

“His head’s too big.”

“His——”

William speedily and joyfully put an end to the duet and Father Christmas wearily disentangled the struggling mass.

“It may be a bit on the small side,” he conceded as he deposited the small bear upside down beneath the table, “but we’ll do what we can.”

Here the shirt-sleeve man appeared at the window.

“That’s right,” he said kindly. “Take all day about it. Don’t hurry! We all enjoy hanging about and waiting for you.”

Father Christmas offered to retire from his post in favour of the shirt-sleeve man, and the shirt-sleeve man hastily retreated.

Then came the task of fitting William into the skin. It was not an easy task.

“You’re bigger,” said Father Christmas, “than what you look in the distance. Considerable.”

William could not stand quite upright in the skin, but by stooping slightly he could see and speak through the open mouth of the head. In an ecstasy of joy he pummelled the big bear, the little bear gladly joined in the fray and a furry ball of three struggling bears rolled out of the door of the hut.

The shirt-sleeve man rang a bell.

“After this somewhat lengthy interlude,” he said. “By the way, may I inquire the name of our new friend?”

William proudly shouted his name through the aperture in the bear’s head.

“Well, Billiam,” he said jocularly, “do just what I tell you and you’ll be all right. Now all clear off a minute, please. We’ve only a few scenes to do here.”

“Location,” he read from a paper in his hand, “hut in wood. Enter fairies with Fairy Queen. Dance.”

“How I am expected to dance,” said the Fairy Queen bitterly, “tortured by toothache, I can’t think.”

“You don’t dance with your teeth,” said the shirt-sleeve man unsympathetically. “Let’s go through it once before we turn on the machine. You’ve rehearsed it often enough. Now, come on.”

They danced a dance that made William gape in surprise and admiration, so dainty and airy was it.

“Enter Father Christmas,” went on the shirt-sleeve man.

“What I can’t think,” said Father Christmas, fastening on his beard, “is what a Father Christmas’s doing in this effect.”

“Nor a giant,” said the giant sadly.

“It’s for a Christmas show,” said the shirt-sleeve man. “You’ve gotter have a Father Christmas in a Christmas show, or else how’d people know it’s a Christmas show? And you’ve gotter have a giant in a fairy tale whether there is one in it or not.”

Father Christmas joined the dance—gave presents to all the fairies, then retired behind the hut to his private store of refreshment.

“Enter Goldilocks,” said the shirt-sleeve man. “Now where the dickens is that kid?”

Goldilocks, fat, fair and rosy, appeared from behind a tree where she had been eating bananas.

She peered down the middle bear’s mouth.

“It’s a new one,” she said.

“The other hasn’t turned up,” said the man. “This is Billiam, who is taking on the middle one for the small consideration of five shillings.”

“He’s put out his tongue at me,” she screamed in shrill indignation.

At this the big bear, whose adoration of Goldilocks was very obvious, closed with William, and Goldilocks’ mother screamed shrilly.

The giant separated the two bears and Goldilocks came to the hut with an expression of patient suffering meant to represent intense physical weariness. She gave a start of joy at the sight of the hut, which apparently she did not see till she had almost passed it. She entered. She gave a second start of joy at the sight of three porridge plates. She tasted the first two and consumed the third. She wandered into the other room. She gave a third start of joy at the sight of three beds. She tried them all and went to sleep beautifully and realistically on the smallest. William was lost in admiration.

“Come on, bears,” said the man in shirt-sleeves. “Billiam, walk between them. Don’t jump. Walk. In at the door. That’s right. Now, Billiam, look at your plate, then shake your head at the big bear.”

Trembling with joy William obeyed. The big bear, in the privacy of the open mouth, put out his tongue at William with a hostile grimace. William returned it.

“Now to the little one,” said the man in shirt-sleeves. But William was still absorbed in the big one. Enraged by a particularly brilliant feat in the grimacing line which he felt he could not outshine, he put out a paw and tripped up the big bear’s chair. The big bear promptly picked up a porridge plate and broke it on William’s head. The little bear hurled himself ecstatically into the conflict. Father Christmas wearily returned to his work of separating them.

“If you aren’t satisfied with your bonus,” said the shirt-sleeve man to William, “take it out of me, not the scenery. You’ve just done about five shillings’ worth of damage already. Now let’s get on.”

HE MET A BOY WHO FLED FROM HIM WITH YELLS OF TERROR,

AND TO WILLIAM IT SEEMED AS IF HE HAD DRUNK OF

ECSTACY’S VERY FOUNT.

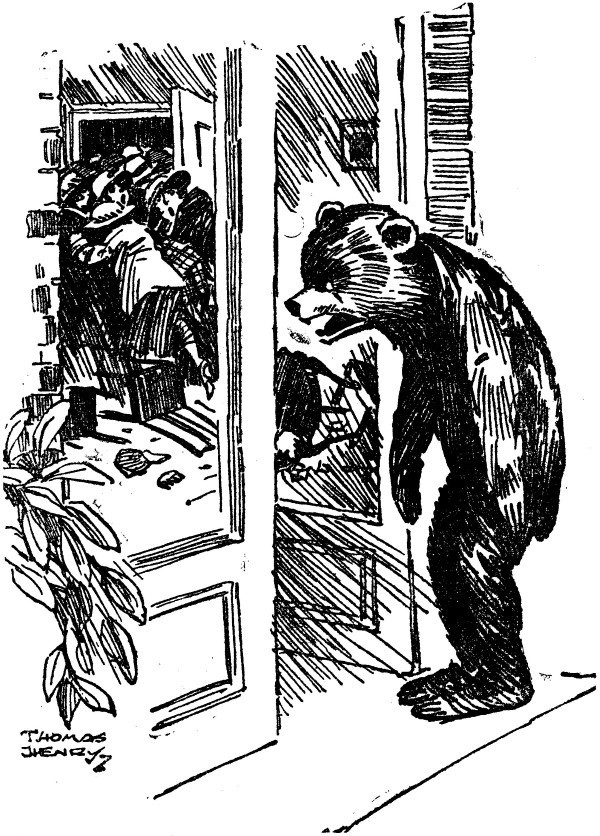

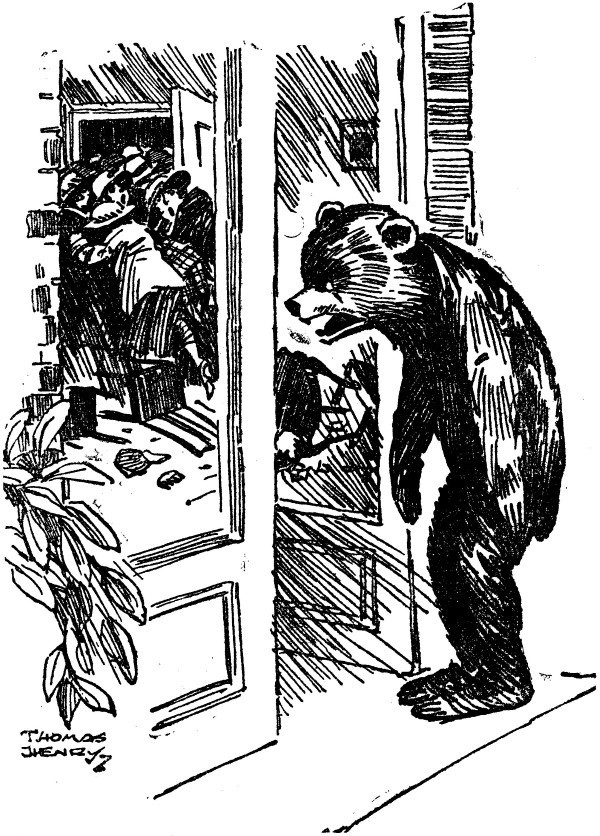

The rest of the scene went off fairly well, but William was growing bored. It wasn’t half such fun as he thought it would be. He wasn’t feeling quite sure of his five shillings after those smashed plates. The only thing for which he felt a deep and lasting affection, from which he felt he could never endure to be parted, was his bear-skin. It was rather small and very hot, but it gave him a thrill of pleasure unlike anything he had ever known before. He was a bear. He was an animal in a pantomime. He began to dislike immensely the shirt-sleeve man, and the hut, and the Fairy Queen, and the giant, and all the rest of them, but he loved his bear suit. It was while the giant was having a scene by himself that the brilliant idea came to William. He was standing behind a tree. No one was looking at him. He moved very quietly further away. Still no one looked at him. He moved yet further away and still no one looked at him. In a few seconds he was leaping and bounding through the wood alone in the world with the bear-skin. He was a bear. He was a bear in a wood. He ran. He jumped. He turned head over heels. He climbed a tree. He ran after a rabbit. He was riotously, blissfully happy. He met a boy who fled from him with echoing yells of terror, and to William it seemed as if he had drunk of ecstasy’s very fount. He ran on and on, roaring occasionally, and occasionally rolling in the leaves. Then something happened. He gave a particularly violent jump and strained the skin which was already somewhat tight. The skin did not burst, but the head came down very far on to William’s head and wedged itself tightly. He could not see out of its open mouth now. He could just see out of one of the eye-holes, but only just. His mouth was wedged tightly in the head and he found he could not speak plainly. He put up his paws and pulled at the head to loosen it, but with no results. It was very tightly wedged. William’s spirits drooped. It was all very well being a bear in a wood as long as one could change oneself to a boy at will. It was a very different thing being fastened to a bear-skin for life. He supposed that in time, if he went on growing to a man, he’d burst the bear-skin. On the other hand, he couldn’t get to his mouth now, so he couldn’t eat, and he’d not be able to grow at all. Starvation stared him in the face. He was hungry already. He decided to return home and throw himself on the mercy of his family. Then he remembered that his family were all out that afternoon. His mother was at a mother’s meeting at the Vicarage. He decided to go straight to the Vicarage. Perhaps the united efforts of the mothers of the village might succeed in getting his head off. He went out from the woods on to the road but was discouraged by the behaviour of a woman who was passing. She gave an unearthly yell, tore a leg of mutton from her basket, flung it at William’s head, and ran for dear life down the road, screaming as she went. William, much depressed, returned to the woods and reached the Vicarage by a circuitous route. Feeling too shy to ring the bell and interview a housemaid in his present costume, he walked round the house to the French windows of the dining-room where the meeting was taking place. He stood pathetically in the doorway of the window.

“Mother,” he began plaintively in a muffled and almost inaudible voice, but it would have made little difference had he spoken in his usual strident tones. The united scream of the mothers’ meeting would have drowned it. Never in the whole course of his life had William seen a room empty so quickly. It was like magic. Almost before his plaintive and muffled “Mother” had left his lips, the room was empty. Only two dozen overturned chairs, an overturned table, and several broken ornaments marked the line of retreat. The room was empty.

The entire mothers’ meeting, headed by the vicar’s wife and the vicarage cook and housemaid, were dashing down the main road of the village, screaming as they went. William sadly surveyed the desolate scene before him and retreated again to the woods. He leant against a tree and considered the whole situation.

“Hello, Billiam!”

Turning his head to a curious angle and peering out of one of the bear’s eye-holes, he recognised Goldilocks.

“Hello!” he returned in a spiritless voice.

“Why did you run away?” she said.

“Dunno,” he said. “I wanted the old skin. Wish I’d never seed it.”

“You do talk funny,” she said. “I can’t hear what you say.”

And so far was William’s spirit broken that he only sighed.

NEVER IN THE WHOLE COURSE OF HIS LIFE HAD WILLIAM

SEEN A ROOM EMPTY SO QUICKLY.

“I saw you going,” she went on, “and I went after you, but you ran so fast that I lost you. Then I went round a bit by myself. I say, they won’t be able to get on with the old thing without us. I heard them shouting for us. Isn’t it fun? An’ I heard some people screaming in the road. What was that?”

William sighed again. Then he shouted: “Try’n pull my head loose. Hard.”

She complied. She pulled till William yelled again.

“You’ve nearly took my ears off,” he said angrily in his muffled, sepulchral voice.

But the head was wedged on as tightly as ever.

She went to the edge of the wood and peered across the road.

“There’s a place there,” she said, “with lots of men in. Go’n’ ask them.”

William somewhat reluctantly (for his previous experiences had sadly disillusioned him with human nature in general) went through the trees to the roadside.

He looked back at the white-clad form of Goldilocks.

“Wait for me,” he whispered hoarsely.

Anxious to attract as little notice as possible, he crept on all fours round to the door of the public-house. He poked in his head nervously.

“Please, can some’n——” he began politely, but in the clatter that arose the ghostly whisper was lost. Several glasses and a chair were flung at his head. Amid shoutings and uproar the innkeeper went for his gun, but on his return William had departed, and the innkeeper, who knew the better part of valour, contented himself with bolting the door and fetching sal-volatile for his wife. After a decent interval he unlocked the door and the inmates crept cautiously home one by one.

“A great, furious brute,” they were heard to say. “Must have escaped from a circus——”

“If we hadn’t been quick——”

“We ought to get up a party with guns——”

“Let’s go and warn the school, or it’ll get the kids——”

On reaching their homes most of them found their wives in hysterics on the kitchen floor after a hasty return from the mothers’ meeting.

Meanwhile William sat beneath a tree in the wood in an attitude of utter despondency, his head on his paws.

“Why didn’t you tell them,” said Goldilocks impatiently.

“I tell everyone,” said William. “Nobody’ll listen to me. They make a noise and throw things. I’m go’n’ home.”

He rose and held out a paw. He felt utterly and miserably cut off from his fellow-men. He clung pathetically to Goldilock’s presence.

“Come with me,” he said.

Hand in hand, a curious couple, they went through the woods to the back of William’s house. “If I die,” he said at once, “afore we get home, you’d better bury me. There’s a spade in the back garden.”

He took her round to the shed in his back garden.

“You stay here,” he whispered. “An’ I’ll try and get my head took off an’ then get us somethin’ to eat.”

Cautiously and apprehensively he crept into the house. He could hear his mother talking to the cook in the kitchen.

“It stood right in the window,” she was saying in a trembling voice. “Not a very big animal but so ferocious-looking. We got out just in time—it was just getting ready to spring. It——”

William crept to the open kitchen door and assumed his most plaintive expression, forgetting for the moment that his expression could not be seen. Just as he was opening his mouth to speak cook turned round and saw him. The scream that cook emitted sent William scampering up to his room in utter terror.

“It’s gone up—plungin’ into Master William’s room—the brute! Thank evving the little darlin’s out playin’. Oh, mum, the cunnin’ brute’s a-shut the door. Oh, my! It turned me inside out—it did. Oh, I darsn’t go an’ lock it in, but that’s what ought to be done——”

“We—we’ll get someone with a gun,” said Mrs. Brown weakly. “We—oh, here’s the master.”

Mr. Brown entered as she spoke. “I’ve got terrible news for you,” he said.

Mrs. Brown burst into tears.

“Oh, John, nothing could be worse than—than—John, it’s upstairs. Do get a gun—in William’s room. And—oh, my goodness, suppose he’s there—suppose it’s mangling him—do go——”

Mr. Brown sat calmly in his chair.

“William,” he said, “has eloped with a jeune première and a bear-skin. An entire Christmas pantomime is searching the village for him. They’ve spent the afternoon searching the wood and now they are searching the village. Father Christmas is drinking ale in a pub. He discovered that William had paid it a visit. A Fairy Queen is sitting outside the pub complaining of toothache, and Goldilocks’ mother is complimenting the vicar on the rural beauty of his village, in the intervals of weeping over the loss of her daughter. I gathered that William had visited the vicarage. There’s a giant complaining of the cold, and a man in his shirt-sleeves whose language is turning the air blue for miles around. I was coming up from the station and was introduced to them as William’s father. I had some difficulty in calming them, but I promised to do what I could to find the missing pair. I’m rather keen on finding William. I don’t think I can do better than hand him over to them for a few minutes. As for the missing damsel——”

Mrs. Brown found her voice.

“Do you mean——?” she gasped feebly, “do you mean that it was William all the time?”

Mr. Brown rose wearily.

“Of course,” he said. “Isn’t everything always William all the time?”