CHAPTER XXIV

JEAN ANSWERS A QUESTION

WAYNE had not appeared for dinner, nor had he shown himself at all during the evening. In the morning, however, when Mrs. Craighill and Jean came down he was waiting for them in the library.

“Your father is coming in at nine o’clock, and I shall meet him with the car. You and Miss Morley had better go in to breakfast now; I will have a cup of coffee with you.”

Jean was to remain until Mrs. Craighill returned with her husband; this had already been stipulated. Mrs. Craighill had made sure of the girl; their evening together had afforded ample opportunity for the strengthening of ties of amity.

She had tested Jean in her own way and found her singularly guileless. In the quiet of Mrs. Craighill’s sitting room she had thrown open doors that revealed the narrow vistas of a happy girlhood; and a certain forlornness due to Jean’s identification, in Mrs. Craighill’s mind, with wet shoes and shabby, bedraggled skirts, yielded to the charm of the girl’s simplicity and candour. It was a revelation to Adelaide Craighill that anyone to whom fortune had flung so few scraps could bring so brave a spirit to the patching together of an existence. She was herself testing the reticulated threads which events had, within a week, woven into an inexplicable pattern.

She wore her hat to the breakfast table and watched coldly the pains Wayne took to interest the girl beside him. It was to Jean’s credit, however, that she seemed properly embarrassed by Wayne’s interest. She turned often to Mrs. Craighill and laughed sparingly at Wayne’s chaff. Wayne was conscious enough of Mrs. Craighill’s displeasure. A man who has played the rôle of love’s adventurer and is at home in the part, does not expect to be a hero to two women at the same table.

Wayne saw Mrs. Craighill off in the motor. She did not ask him to accompany her or offer to carry him downtown. He returned to the table and concluded his breakfast. Jean rose at once when he had finished and went into the library where she sought refuge in a magazine; he took this as notice that his presence was not necessary, but after walking back and forth between the fire and the windows several times he sat down near her.

“There’s something I should like to say to you.”

“Well?” and she looked up without closing the magazine.

“I never knew until last night that you were Mr. Gregory’s granddaughter.”

He had spoken the least bit tragically and she smiled.

“Yes, he is my grandfather. I understand perfectly that I shouldn’t be here, in your father’s house, with my grandfather feeling as he does toward Colonel Craighill; and I’m sorry about it.”

“I’m sorry, too—sorry about that unpleasant business matter. I have offered to settle your grandfather’s claim. I should like you to know that I acknowledge the justice of it.”

“But it’s not the point for you to acknowledge it. It’s only partly a money matter; there’s more to it than that—at least, that’s grandfather’s way of looking at it. Mrs. Craighill asked me to stay until she came up from the station and I suppose I shall have to see your father this morning.”

“Yes; I imagined she had asked you. She did it out of compliment to me!”

The colour stole into her face. She was not so dull but that she saw why Mrs. Craighill had kept her at the house. Jean took up her magazine and began reading.

“Please pardon me! I should not have said that.”

She nodded slightly, without looking up. Her flushed cheeks told him plainly enough that she had grasped the whole situation at Rosedale and he was angry at himself for having referred to it.

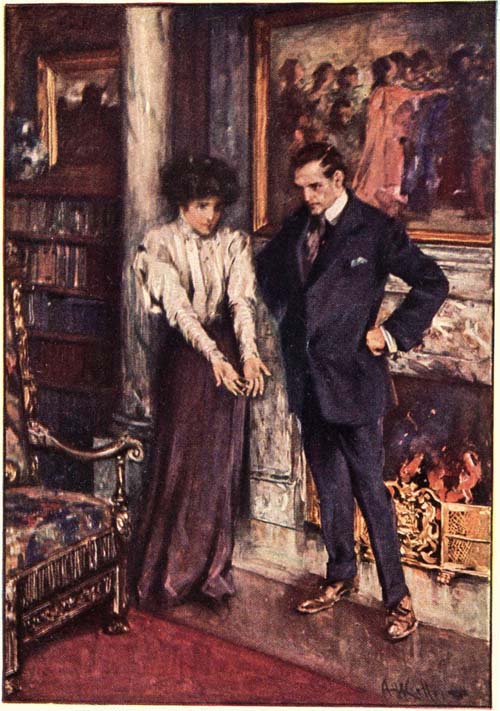

“There is nothing in the world so important to me as your good opinion,” he said, standing before her.

She closed the magazine upon her hand and looked up at him.

“This isn’t quite fair of you, is it? I am in your house, and I can’t very well run away. Please let us not talk of you and me.”

There was no sympathy in her tone; she had spoken with quiet decision with the obvious intention of being rid of him.

“When I met you at the concert and walked to my sister’s that evening I thought we were understanding each other. Has anything that happened since changed the situation as we left it that day?”

“I wish you wouldn’t! Please do not! It is very unfair and unkind. You know perfectly well that I cannot discuss such a matter with you; and what difference does it make one way or another?”

“I have no claim on your mercy. I cannot explain anything. I want the right to earn your good opinion; that is what I am asking.”

“But why should you be asking? What difference does it make whether my opinion of you is good or bad? It is absurd the way we meet. Every meeting has been a little more unfortunate than the last—if for no other reason than that it has been another one! It is quite possible that I have lost your sister’s friendly interest by that walk home from the concert. You must have seen that she didn’t like it; and she was perfectly right not to like it. Nothing could have been more ill-advised and foolish than our going to her house together.”

“Oh, if it’s only Fanny! Fanny understands everything perfectly.”

“That isn’t very comforting, is it?” she asked with the least tinge of irony. She seemed more mature than he had thought her before, and she was purposely making conversation difficult. In a few minutes his father and Mrs. Craighill would return and he must make the most of his time. His tone was lower as he began again, on a new tack, and she listened with reluctant attention.

“When I met you I was well started to the bad and I had every intention of keeping on. I was going to do a particular thing and it was vile—it was the worst. Why is it that you are standing in the way of it? Oh, I know you don’t understand—if you did you wouldn’t let me speak to you; but it’s because you don’t understand—it’s because you couldn’t understand, that it’s so strange that you are blocking me. And not only that, but here you are in this house—this house that was my mother’s, and you bring her back to me as you sit there—just where she used to sit. The sight of you makes all these later years of my life hideous to me: I can’t do the thing I meant to—I see how foul it was; and I’m saying this to you now because I’m afraid of losing you—I’m afraid of your going away where you can’t help me any more.”

She had been obliged to read much into his strange appeal; it was as though he turned the leaves of a book swiftly, disclosing only half-pages, with type blurred and indecipherable. She looked at him wonderingly; there was a cry in his last words that touched her. It had been easy the day before to simulate feeling in his assault upon Mrs. Craighill’s emotions at Rosedale but he had no wish to deceive this girl. Her eyes forbade it; and it was not so long ago that the sharp lash of her scorn had struck him in the face: “I don’t care for your acquaintance, Mr. Wayne Craighill.” She was saying now:

“I am glad if I have ever helped you, though I don’t in the least understand how that could be. It is not for me to help anyone. No one who isn’t strong can help another; we must be sure of ourselves first, and I am weak and I have made sad mistakes; I have done harm and caused heartache. And more than that, we belong to different worlds, you and I. I have tried to say this to you before, but we must understand it now. Our meetings have certainly been strange, but as I told you, I’m not superstitious. Very likely we shall never meet again, and you will go on your way just as though you never had seen me, and I will go about my business—and so——”

“But if you knew I was going to the bad, and you could save me and I asked you to help, would you feel the same way about it? Maybe the answer is that I’m not worth saving!”

She smiled at this, but his appeal touched her. He was nearly ten years her senior, and belonged, as she had said, to an entirely different world, and he wanted her help and begged for it. She felt his charm and realized the danger that lay in it, and she wished to be kind, but here was a case where sympathy must be offered guardedly. This interview was altogether too serious for comfort and she rose, facing him with an entire change of manner. It seemed that she was the older now, the one grown wise through long familiarity with the world.

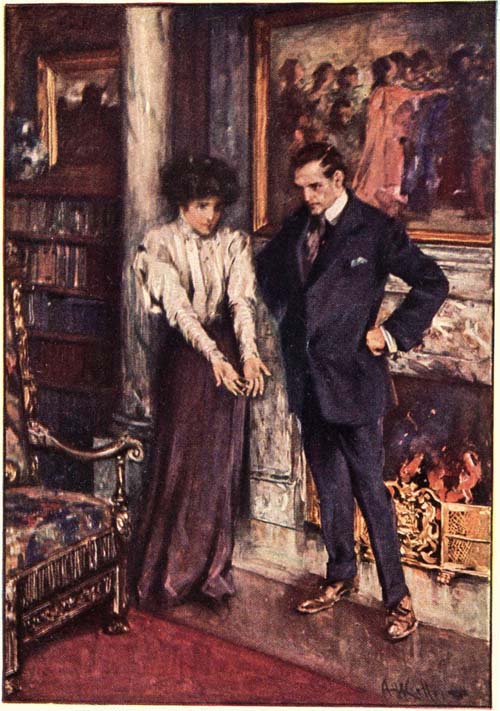

“MEN WHO WORK WITH THEIR HANDS—THESE THINGS!”

“I’m a busy person, Mr. Craighill; I’m working just as hard as I can and I hope to do something pretty good one of these days, in spite of the gloomy view I take occasionally of my prospects. Now, why don’t you go in for something? Work, work, work! It’s the only way to be happy. You haven’t won the right to the leisure you’re throwing away. It’s cheating life to waste opportunities as you do. I saved just half a dollar a week for two years to get a chance to study drawing; I scrubbed and washed dishes in a hotel and ran a machine in a garment factory. And you may be sure that if I have to do it I’ll go back to the sewing-machine next summer and begin all over again without the slightest grudge against the world. I’m not going to be a beggar; I want to earn my right to a share in beautiful things.

“Why, Mr. Craighill,” she continued with increasing vehemence, “all the men I have ever known have been labouring men—men who work with their hands—these things!” In her passionate earnestness she held out her hands as though they were part of her case for labour. “My father was an anthracite miner, and he died at work. I’ve seen sad things in my life. I had a little brother who was crushed to death in a breaker. He was oiler boy, and he was so eager to get time to play at noon with the other boys that he crawled in to do his work before the machinery stopped and he was ground to pieces—fourteen years old, Mr. Craighill! I can’t get over that—that he was a child and he died trying to win time away from labour to play! I’ve seen them bring bodies of dead men out of mines all my life—my own father was killed by a fall of slate—but I’d rather sweep the streets, if I were you, or dig ditches, or drive mules down in the dark than just be—well, nothing in particular but somebody’s son with money to spend—and not the least bit of sense about spending it!”

Wayne Craighill had been scolded, and nagged, and prayed over without effect, but this speech was like a challenge; there was a cry of trumpets in it. And her reference to the dead men of the pit, and the mordant scorn of her last phrases set his blood tingling. He was aware now that it was a sweet and precious thing to be near her: no other voice had power to thrill like hers; no other eyes had ever searched his soul with so deep and earnest a questioning.

“If I will labour for you—if I will work with these hands for you”—he held them out in unconscious imitation of her own manner a moment before, looking down at them curiously—“will you take my life, what I can make of it, and go on to the end with me—you and I together?”

She shook her head, though with a smile on her lips.

“No! That is an impossible thing. And this idea of my helping you—I haven’t the least bit of patience with that—not the least. You were born free but you have wasted your freedom. If once you were to labour with your hands—to know the toil of the men down below—you would see life differently, and all beautiful things would mean more to you. You are big and strong and you can be a man if you want to be. But I’m going to do a foolish thing—the most foolish thing I could do, I suppose—I’m going to be friends with you—just as long as you will let it be that; and I’m saying this—I wonder if you know why?”

“You are kind, that is all I need to know.”

“I’m not in the least kind—don’t misunderstand me. But,” she smiled brightly, confidently, “I trust you; I believe in you; and I like you. If that suits you I’m ready to begin.”

She put out her hand with a frank gesture and her smile won him to instant acquiescence, though there were stipulations he wished to make as to this new relationship. He caught a glimpse of the motor bringing his father and Mrs. Craighill from the station as it flashed past the windows to the carriage entrance. The desire to possess, to protect, to defend this woman set his heart singing. She did not fear him, an evil, abhorred castaway, an ugly wreck on the shoals of time; she had spoken to him rather as a man might have done, but his response was to the woman heart in her. His hand trembled in her clasp, and the wholesomeness, the sweetness, the earnestness of her own nature kindled the hope of life in his heart. He felt a new ease, as of lifted burdens, and a light was round about him; and well for this exalted moment that he could not see ahead into the circling dark.

“Good-bye, Jean!” He bent down and held her hand an instant to his cheek—the hand that had known labour!

“Good-bye, Wayne Craighill,” she replied, soberly.

A moment later he left the house by the front door, unnoticed by his father and Mrs. Craighill, who at the same moment appeared in the side hall.