CHAPTER III

RAROTONGA

RAROTONGA is one of the fairest islands in the world. It has a white sandy beach; within that lies a belt of rich land. On this land, and even on the lower slopes of the mountains that tower one above the other in the centre of the island, banana trees, chestnuts, and cocoanut palms grow in clumps.

Tamate and Tamate Vaine quickly settled down to their work in Rarotonga. The life there was very quiet after the constant change and danger of the voyage.

The people who lived in Rarotonga called themselves Christians. They had given up fighting and the worship of the strange wild spirits whom their fathers had thought to be full of power. But though they had done this, many of them were still selfish and lazy.

Tamate would have liked to go at once amongst men who were much wilder, and who had never heard of the God who is love.

When he saw what his work in Rarotonga would be, he wrote to England to those who had sent him. He asked them to send some one else to Rarotonga, some one who would like to work quietly and to teach; and to let him go to a more dangerous place, where he could make it easier for others to follow him. But no one else could be sent then, and he could not leave his post.

When he found that he must stay in Rarotonga, he made up his mind that since he could not get the work he wished, he would throw all his strength into the work he had to do.

Part of it was to train native lads so that they might become teachers and go to other islands. Though they were men, he had to teach them a great many things that boys and girls learn at home when they are very little. He had to train them to be thrifty, and tidy too, because, when they went away to teach they would have to till their own gardens, and to grow their own crops, and to be at the head of a school without any one to guide them.

As Tamate spoke to the people in church Sunday after Sunday he wondered where all the young men were. There were old men and women, and young women and children, and there were his students, but he scarcely ever saw any other young men.

Where could they be?

He found that they spent their days, and often their nights too, in the thick tanglewood that is called “the bush,” and that they drank orange beer there, and sometimes foreign drinks too. These revels made them useless for anything else.

The natives who knew Mr. Chalmers, and were beginning to love him, begged him not to go near the young men when they were drinking, because they were wild and fierce, and might kill him.

But Tamate never was afraid of any one. He went away alone, and plunged here and there through the bush, until he came upon a band of young men. Then he sat down and chatted with them. Very soon they liked him so much that though they would not give up drinking, yet they could forgive him when he knocked the bungs out of the beer barrels and let the beer run away. He was so brave and fearless that he could do this when the men were standing watching him.

Sometimes one or two of the young men gave up drinking, but Tamate wished to get hold of them all, not of one or two only, so he kept on winning their friendship, and waited.

His chance came. He heard that the young men were meeting to drill for war, and that they called themselves volunteers. This was startling. War had ceased on the island. No one was likely to attack them from over the sea. Why should they drill?

Tamate thought of the battles of Glenaray. He knew it would be useless to talk to these wild lads about peace and kindness, but he thought of another plan. He said to them:

“Why do you drill out of sight like this? Why not let every one see that you are ‘Volunteers.’ You must come to church, and sit together in the gallery.”

The first Sunday after that a few of them came to church. The next week many more came, and from that time the Sunday Service became part of their drill. So eager were they to look well when they came to it, that they began to plant their lands that they might sell the fruit they grew, and buy clothes.

Coral for the new staircase

By-and-by the little church in Rarotonga needed a new platform and a new staircase. Then a great joy came to Tamate. He saw his young bushmen, whom he had first seen round their midnight fires, wild and fierce and useless, away out on the reefs cutting coral for the new staircase. They had learned to love the church and its services, and some of them became soldiers in the army of Jesus Christ.

When the church was ready to be opened again, there was great eagerness and stir. The natives had given nearly all that was needed. But there was still £25 worth of wood unpaid for.

Tamate was sure that the gifts that would be brought on the opening day would be worth much more than £25, but when he said so to a group of men, the doorkeeper said to him:

“How are you going to get in?”

“Why, by the door, of course.”

“No, you will not. I have the keys, and I will not open the door until everything is paid. Of course you may try the windows.”

Tamate was very glad that his doorkeeper cared so much about this debt. Though he had not meant to be so strict, he yielded to his friend.

But although the doorkeeper would let no one enter a church that was not paid for, he did not mean to keep any one out of church for a single day.

Soon a great noise was heard in the village. Boom went the drums. Boom! boom! High above their booming the voices of the villagers rose. Every one was called together to give what they could spare for the church. Very soon all was paid, and many gifts were left over.

All the time that Tamate was in Rarotonga he was longing to be at more dangerous work amongst those who lived to fight and kill each other, and who had no one to teach them.

His thoughts were so much with these wild tribes that he made others think of them too. Many of his students had caught his spirit, and longed, as he did, to go to the island of New Guinea, where very wild men lived and fought. Some of the teachers he had trained went before him. They knew it was dangerous, but they went with joy, because they too had learned how great and glad a thing it is to live for others.

At last Mr. Chalmers was allowed to leave Rarotonga and to go to New Guinea.

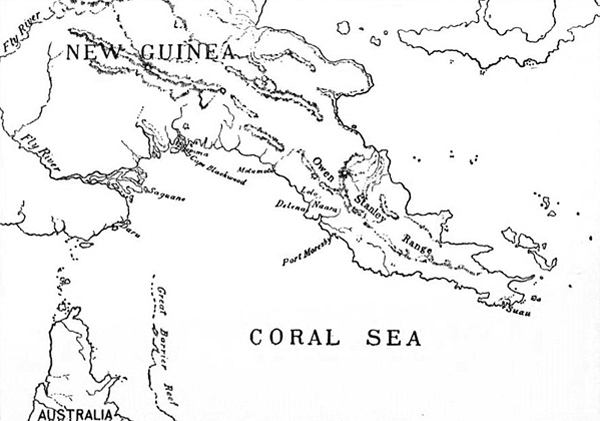

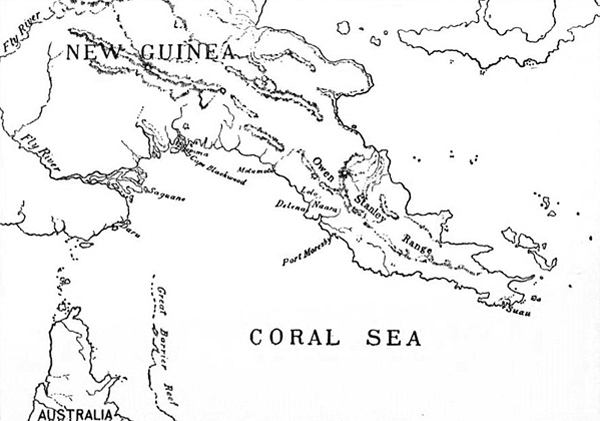

New Guinea is an island three times as large as Great Britain. It is very rich in fruits, in ebony wood, and in other things that traders like to find. It lies near to Australia. But the savages who lived in it were so fierce, and its rocky coast was so wild, that no one had tried to trade in the south-eastern end of it. Those who knew anything about it thought that to go there meant to die.

Four years before Tamate went to New Guinea, some of his teachers had landed at one of its villages, which was called Port Moresby. Here they found Mr. Lawes and his wife, who some months earlier had made their home there. They were the first white people who had lived amongst the natives of that wild coast. They found many tribes of natives, and each tribe was at war with the tribes around it. If two chiefs had a quarrel with each other, they brought their tribes to fight it out. Then the two tribes went on paying each other back in turn, till all their villages were burned and very many of their warriors were killed. Every one was either killing, or being killed, or afraid of being killed.

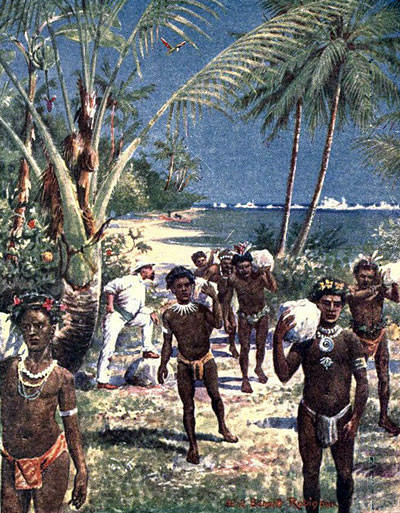

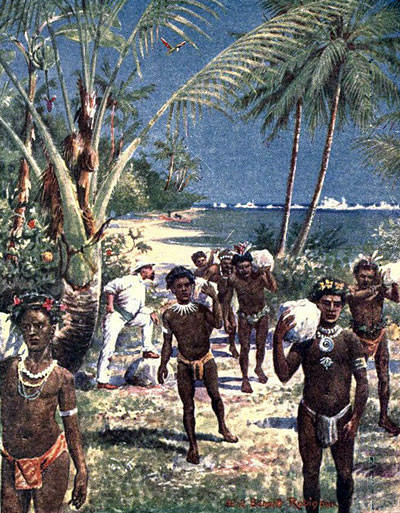

The men of New Guinea were large and strong, and they liked to look handsome. They thought it very handsome to have their hair standing far out on the tops of their heads and all round, with beautiful bright feathers stuck into it. They liked, too, to wear sticks like tusks through their noses, and rings through their ears, and necklaces of bones.

They daubed themselves all over with bright, sticky paint. But what they thought most handsome of all was to have a great many tattoo marks. When a man had killed another he was allowed to have his skin pricked with coloured dye. Afterwards the dye would never come out, no matter how hard the skin was scrubbed.

No one was allowed to have these coloured marks until he had killed a man. That was why the wild men of New Guinea were so proud of tattoo marks. Each mark proved that the man who bore it had been strong and clever.

It did not always prove that he had been brave, because sometimes the spear that had killed had been thrown from behind the foe.