CHAPTER XI

THE FLY RIVER

AFTER Mr. Chalmers returned from this voyage, he and his wife went away to the mouth of the Fly River. The men of the wild tribes who lived there were not nearly so lovable as the savages of Motu-motu, and Mrs. Chalmers found it difficult to care as much for the ugly cruel children of the island of Saguane, where their home now was, as she had done for the children at Motu-motu.

Many new plans were in Tamate’s mind. It was not enough for him that schools and churches were rising throughout New Guinea; that war was ceasing; that, when he landed at scattered villages, men and women were waiting his coming, to say openly to all, that they meant to follow Jesus Christ. He always wanted more. As long as those wild tribes of the Fly River fought and hated each other he could not rest. He wished to do more for them than to bring peace amongst them. He hoped that some of the men of those tribes at the mouth of the river, who had learned to love his Master, would go to live inland amongst the swamps and marshes, where even his Rarotongan teachers could not live. So he began to train a band of these natives, as he had trained the men of Rarotonga and Port Moresby before.

In the midst of all his plans his wife grew very ill. He nursed her for three months, but her strength sank. The sea was washing away the shore of the island of Saguane where they lived, and they found they must leave it. They went to Daru, a village on the mainland, but Mrs. Chalmers only lived one day there. She had been very eager to reach this new home, which was to be her last on earth. Her wish came true. She was buried in the native graveyard, and her husband was left once more to work in loneliness.

He did not lose courage. He threw himself more keenly than ever into his work. But his own strength was failing, and he found it harder to go long journeys without rest. Sometimes he thought he was growing lazy when he felt that he was not able to do as much as he had once done.

One morning he set sail on the Nieu, which had taken the place of the Harrier, for Cape Blackwood. The natives there, and on the large island near, were very strong and fierce. Tamate knew that he might be killed, but then he knew, too, that if he could win those wild men, he would take away the great barrier between Christ and the tribes who lived round the gulf of water into which the Fly River flowed. If these men were to stop fighting and to listen to the story of Christ, other tribes would be glad to do so too. They would be grateful to be free from the fear of these cruel warriors.

It did not matter much to Tamate whether it was by his life or by his death that he won them. Either way he must break down the wall that shut out the joy of life from so many people.

There was a young friend who had come to New Guinea with the same hopes that Tamate himself had. This friend had been with him for a year, and had been like a son to him in his sorrow. He went with him on this voyage. Besides these two, there were on board Hiro a teacher, Naragi a chief, ten boys who were in training, and the captain.

When the Nieu came to the island, she anchored near the village of Dopima. When the villagers saw the ship, they ran down to the shore and tumbled into their canoes. In a very short time the Nieu had canoes lying all round her, and natives were climbing up her sides. No one could say how many of them there were. Savages had often come on board when Tamate’s ship lay at anchor, but these seemed to be more wilful and fierce than most of the others had been.

At last, as the sun went down behind the island on which their village stood, Tamate ordered them to go home, and said that if they went at once he would land at Dopima and see them next day.

They went away, but when the morning came they would not wait till he could keep his promise. At five o’clock their canoes crossed the water to the Nieu. There were many more of the villagers than there had been on the evening of the day before. The deck was so crowded that the men on board could scarcely move about. All around them on their own ship there were dark and angry faces, and in their ears was the clamour of excited voices.

It was not a peaceful welcome that the canoes had brought. They were full of bows and arrows, clubs and spears. Tamate bade the natives begone, but they would not. Then he thought that if he went himself, although it was so early, they would follow him.

He left the Rarotongan teacher with the captain in the Nieu. He wished his young friend to stay too. He did not wish him to risk his life, because he hoped that he would live a long time, and carry on the work that he himself had begun. The two men looked at each other. They knew there was great danger. They had seen the hatred and bitterness in the faces of the wild men around them. But Tamate had said he would go. He had never failed to keep his promise to the men and women he sought to help. He would not do it now. And his friend would never let him go alone with that wild mob. The two men stepped into the boat together. The chief and the ten boys joined them, and they rowed for the shore.

The splash of the oars sounded faintly through the shrill shouts of the natives. But Tamate’s clear voice rang over all the noise. “Back in half-an-hour to breakfast.”

A rush of canoes followed the boat. But those in her looked anxious when they saw how many canoes stayed by the Nieu. What could two men do if the natives tried to take the ship?

When the boat reached Dopima the two white men and some of the boys landed and went to the great clubhouse. It was the place where all the fighting men met. The other boys stayed to take care of the boat, but soon villagers came to tell them that they too must come to the clubhouse to eat. To feast together is a sign of peace. Tamate was never willing to refuse to eat with the natives. His boys knew this, and left the boat by the shore.

As they feasted in the clubhouse a crash was heard. Naragi and the boys who had come from Daru sprang up. Before them Tamate and his young friend lay dead.

None of them had noticed two armed men who crept along the floor behind the white men till with two blows from their great stone clubs they killed them both.

No one had ever been able to look in Tamate’s face and still be angry with him. But from behind a native had had courage to strike him. His eyes could not awe the savage then.

He lay dead. His boys had no hope of escape. One by one they fell beside their master. Naragi fought for his life. He had no weapons, but when he saw the white men fall, he leapt forward and seized another man’s club. But one man could not stand long against all those howling warriors, and soon he too lay quiet and still.

The men from the clubhouse went down in triumph to the shore to welcome the others who had stayed by the ship. Their canoes, which had shown only weapons, were now piled high with everything that could be lifted from the Nieu. The savages danced and shouted on the beach as they saw the things that had come from the white man’s ship. The men were smeared with war paint, and the clothes and books that had been on the Nieu were soon stained all over as one wild man after another pounced on what he liked best.

After a time they began to tire of turning over the treasures. A shout rose: “Let us break the boat!”

They scampered off to the creek where the boys had left her. Smash! bang! crash! the stone clubs fell on the beautiful boat. She was the last gift that Mrs. Chalmers had given to the work her husband loved. Crack! crick! went the wood. In a few minutes there was only a pile of splinters. Each warrior took one. Afterwards he stuck it up in his clubhouse to show that he too had had a share in the death of the great white chief.

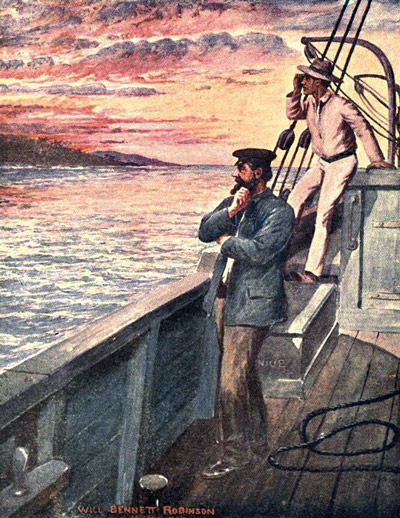

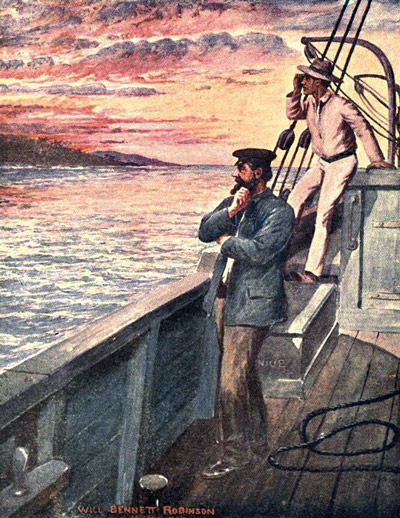

On board the Nieu the captain and Hiro had sent hurried glances after the boat as she went towards the shore. They could not look for long at a time, for they had to try to keep the natives from breaking and wrecking the ship. They saw the boat grow smaller and smaller. They saw the canoes close in upon it. Still they could trace its course. They saw it reach the village and go close to the shore. Then it came out into deep water again. Again it entered the village, and after that they could not see it any more.

No boat came

No clear sounds came to them from Dopima, but around them were many sounds. Everything that could be taken was seized and thrown into the canoes. It was hard to see good things broken and soiled. But the pain of that was nothing to the pain that Hiro and the captain felt as the hours went on and no signal reached them from the shore.

At last the savages left them and quiet settled down on the ship. The quiet was more dreadful than the noise of the morning had been. It left time to look and look towards the shore for the boat that would never come again.

The Nieu lifted her anchor and steamed up and down. All day long she waited near Dopima. After sunset she sailed out to sea beyond the island and anchored there. Next day she sailed along the shore again. The two sad men on board gazed towards the village but no boat came.

At last they sailed to Daru to tell that the great white chief had died for his people.

Yet Tamate did not wish his friends to think of him as dead, when they could not see him any more. He wished them to know that he lives and works gladly in the great life beyond the grave, and that he knows and loves his Master Jesus Christ far better than he could on earth. Not very long before he died, he had written of the life after death, “I shall have good work to do, great brave work for Christ.”

As the news of Tamate’s death came to Daru, and Motu-motu, Port Moresby and Suau, and to all the villages between them, New Guinea was stricken with sorrow. Men and women and children were sick with grief.

Then the love they had for Tamate brought a new strength. They wished to do more for the work for which he died than they had ever done before.

There was one old man called Rua. His hands were weak but his heart was strong. It was so good and strong that though it had loved Tamate with passion, it did not hate the men who had killed him.

Rua sat and mourned. His heart knew the thoughts of the white chief’s heart. Tamate had longed to win the love of the wild men of Dopima for Jesus Christ. He had died for this. Would his death be in vain? No, it must not be! It might be that Rua could help. He might live for the people for whom his friend had died. The thought fired him. He wrote:

“May you have life and happiness. At this time our hearts are very sad. Tamate and the boys are not here. We shall not see them again. I have wept much. My father Tamate’s body I shall not see again, but his spirit we shall certainly see in heaven, if we are strong to do the work of God, thoroughly and all the time. Hear my wish. It is a great wish. My strength I would spend in the place where he was killed. In that village I would live. In that place where they killed men, Jesus Christ’s name and His word I would teach to the people, that they may become Jesus’ children. My wish is just this. You know it. I have spoken.”

Rua could not go to Dopima. A greater joy came to him. Instead of going there to live for Christ and for his friend, he went on a longer journey, to be with Christ and with his friend.

In the clubhouses round Dopima the warriors had stuck up pieces of the broken boat. They pointed to them at their feasts as the signs of their great victory over the white chief and his power.

But in Dopima and all over New Guinea, the death that had seemed to give them the victory was in truth a triumph for the army of Christ. Weak hearts grew brave at the thought of it. Men and women came forward to fight for the Hero whom Tamate had followed even unto death, Jesus Christ, who died for those who hated Him, because He loved them.

THE END