CHAPTER I

BOYHOOD IN ARGYLL

JAMES CHALMERS was born sixty-five years ago at a little town in the West Highlands of Scotland. He was the son of a stonemason, but his home was close to the sea, and he was more eager to sail than to build.

One kind of building he did try. That was boat-building. But he and his little friends did not find it as easy as it looked, so they gave it up and tarred a herring-box instead. When it was ready James jumped into it for “first sail.” His playmates on the beach towed him along by a rope. They were all enjoying the fun when the rope snapped, and the herring-box, with James in it, danced away out to sea. A cry was raised and a rush made for the shore. The fishermen were fond of the daring little fellow who was always in mischief. Soon they caught him and brought him safe to land. But they shook their heads when they saw how fearless he was. They knew he would soon be in some other danger.

When James was seven years old he left his first home and went to live in Glenaray, near Inveraray. Still the mountains of Argyll rose round his home. They were dim misty blue in summer, but in autumn and spring they were strong deep blue like the robes in stained-glass windows. But the new home was not on the sea-shore. James could not tumble about in boats and herring-boxes all day long as he had done before.

Soon he found another kind of daring to fill his thoughts. From his home in Glenaray he and his sisters had three miles to walk to school. Other boys and girls crossed the moors from scattered farm-houses and crofts. A large number of children came from the town of Inveraray, and they gathered to them others whose homes lay between the town and the school. Here were two parties of young warriors ready to fight. James and the moorland groups were the glen party. The others were the town party. Some trifle started warfare. First there was a teasing word, then a divot of turf, and then before any one knew what had happened, stones were flying and fists pounding, and the clans were at war once more on the shores of Argyll.

The spirit of battle ran so high that on fighting days James and his sisters did not go straight home. They joined the larger number of the glen party and went round by the homes of the others, so that they had only the last little bit to go alone. There they were safe from the foe. But on days of truce they went with the town party to the bridges over the Aray. The Aray is a wild mountain stream, and when rain falls in the hills, it rushes wildly down and carries all before it.

One afternoon, when the sunshine had burst out after heavy rain, the children were going home together. As they came near the bridges the rush of the water and its noise drew them close to the banks of the stream.

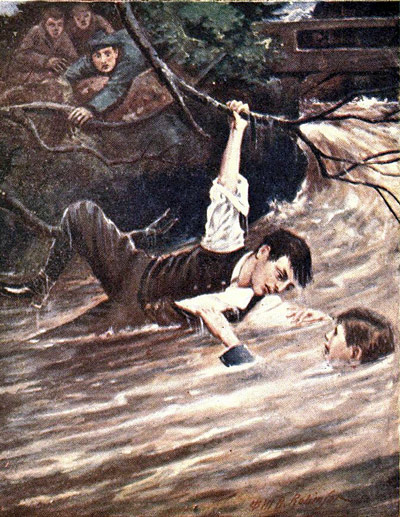

James was there. He heard a cry: “Johnnie Minto has fallen in!”

He threw off his coat and gave a quick glance up the stream. There he saw Johnnie’s head appear and disappear in the rush of the water. Without a moment’s thought he slid down to the lower side of the bridge and caught his arm round one of its posts. Just above him Johnnie was tumbling down in the wild water. One quick clutch and James held him firmly. The water was so fierce and rapid that it seemed he must let go. He did let go, but it was the bridge that he lost hold of, not the boy! He let the current carry them both down till he could catch a branch that overhung the water. By it he pulled himself and his little foe (for Johnnie was of the town party) towards the edge of the stream till the other boys could reach them and drag them on to the bank.

A branch that overhung the water

Once James heard a letter read that had come from an island on the other side of the world. It told of the sorrows and cruelties that savages have to bear. He was touched. The stories of hardship made him wish to do and dare all that the writer of the letter had dared. The stories of sorrow made him long to help. He said to himself that he too would go when he became a man.

But soon he forgot all about that, and thought only of how much fun he could get as the days passed.

As he grew older he became very wild. He could not bear to meet any one who might urge him to live a better life.

He entered a lawyer’s office, but the work did not interest him, and he filled his free time with all kinds of pranks, so that soon he was blamed for any mischief that was on foot in the town.

He was the leader of the wildest boys in Inveraray, but he himself was led only by his whims and the fancy of the moment. Until one day he found his own leader, who made work and play more interesting and delightful than they had ever been before.

James found that his life was not aimless any longer. It was full of one great wish—the wish to serve his hero, Jesus Christ.

Then he thought of his old longing to go and help those who were in pain and sorrow far away from Scotland.

It was not only because he was sorry for them, and because he wished to do the brave and daring things that others had done. These thoughts still drew him on. But far more than these, the love he had for his newly found Master made him wish to go.

He felt that it was a grand thing to be alive and young, and able to do something to bring to other lives the joy and strength that had come into his own.

Before he could go, however, he had to learn many things.

He went to stay at Cheshunt College, near London. The head of the college was a great man. It made it easier to be good to live beside him. Often afterwards, amongst hardships and dangers, his students thought of him, and of what he had said to them at Cheshunt, and were braver and stronger because of him.

While James Chalmers was at college, part of his work was to preach at a village eight miles away, and to go to see the people who were in trouble there. He was a big strong man, and enjoyed his walk of sixteen miles. Perhaps that was why this village, the farthest from the college, was placed under his care. The people there loved him, and to-day they still are glad to think that the “Apostle of New Guinea,” as he was afterwards called, once preached and worked amongst them.

Mr. Chalmers could be solemn when he spoke of God and of life and death, and when he was with the villagers in times of sorrow and pain. But he still enjoyed all the glad things of life that he had loved in his boyhood, boating and swimming and fun of all kinds.

If he was in a restless mood when the others wished to study, the only way they could make him quiet was to give him charge of his part of the house. Then woe betide the man who made a noise. If some one else tried to keep order and he wished to romp, nothing would silence him.

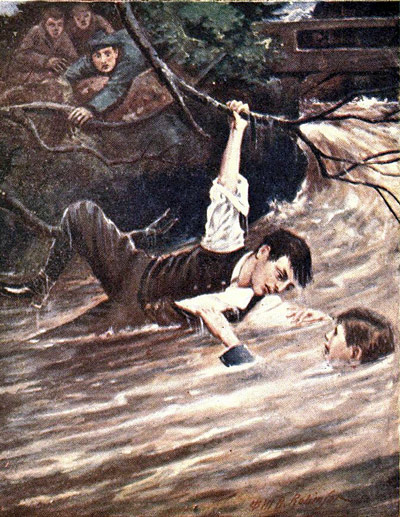

One evening at supper time, as the students sat talking round the table, they heard a slow lumbering step in the passage. “Pad-sh, pad-sh,” it came, nearer and nearer, till the door burst open, and a great grisly bear walked in on his hind legs. The men started up. The bear shuffled in amongst them. He grabbed a quiet timid student. Then the lights went out!

The great grisly creature

There was a great scrimmage. No one knew where the bear was, and no one could find matches. Even brave men did not wish to be caught in the dark by a runaway bear!

When at last the lights were lit, and they saw a man’s face looking out from under the great head of the bear, they did not know whether to laugh more at him or at themselves.

They had been jumping here and there and dodging about, to get out of the way of James Chalmers in a bearskin!

The students were not the only people who were alarmed at the made-up bear. There was an Irishman who came to the college to sell fruit. One day, as he found his way along the halls, he met the bear. It was at the end of a passage, and they met so suddenly that the poor Irishman could save neither himself nor his basket from the paws of the great grisly creature.