2. Introduction to PowerShell for Unix people

The point of this section is to outline a few areas which I think *nix people should pay particular attention to when learning Powershell.

Resources for learning PowerShell

A full introduction to PowerShell is beyond the scope of this e-book. My recommendations for an end-to-end view of PowerShell are:

-

Learn Windows PowerShell in a Month of Lunches - Written by powershell.org’s Don Jones and Jeffery Hicks, I would guess that this is the book that most people have used to learn Powershell. It’s ‘the Llama book’ of Powershell.

-

Microsoft Virtual Academy’s ‘Getting Started with PowerShell’ and ‘Advanced Tools & Scripting with PowerShell’ Jump Start courses - these are recordings of day long webcasts, and are both free.

unix-like aliases

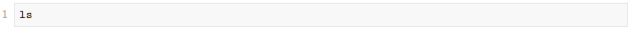

PowerShell is a friendly environment for Unix people to work in. Many of the concepts are similar, and the PowerShell team have built in a number of Powershell aliases that look like unix commands. So, you can, for example type:

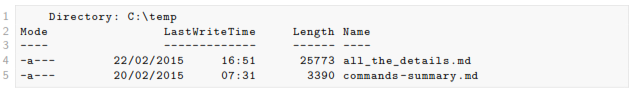

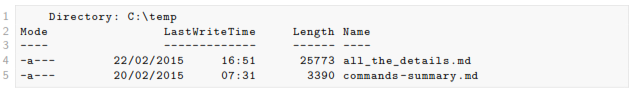

….and get this:

These can be quite useful when you’re switching between shells, although I found that it can be irritating when the ‘muscle-memory’ kicks in and you find yourself typing ls -ltr in PowerShell and get an error. The ‘ls’ is just an alias for the PowerShell get-childitem and the Powershell command doesn’t understand -ltr[1].

the pipeline

The PowerShell pipeline is much the same as the Bash shell pipeline. The output of one command is piped to another one with the ‘|’ symbol.

The big difference between piping in the two shells is that in the unix shells you are piping text, whereas in PowerShell you are piping objects.

This sounds like it’s going to be a big deal, but it’s not really.

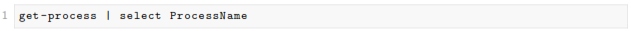

In practice, if you wanted to get a list of process names, in bash you might do this:

…whereas In PowerShell you would do this:

In Bash you are working with characters, or tab-delimited fields. In PowerShell you work with field names, which are known as ‘properties’.

get-help, get-command, get-member

get-member

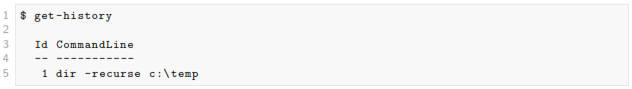

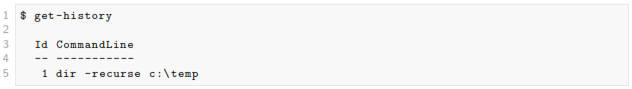

When you run a PowerShell command, such as get-history only a subset of the get-history output is returned to the screen.

In the case of get-history, by default two properties are shown - ‘Id’ and ‘Commandline’…

…but get-history has 4 other properties which you might or might not be interested in:

The disparity between what is shown and what is available is even greater for more complex entities like ‘process’. By default get-process shows 8 columns, but there are actually over 50 properties (as well as 20 or so methods) available.

The full range of what you can return from a PowerShell command is given by the get-member command[2].

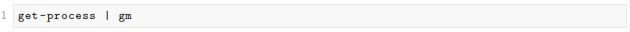

To run get-member, you pipe the output of the command you’re interested in to it, for example:

….or, more typically:

get-member is one of the ‘trinity’ of ‘help’-ful commands:

-

get-member

-

get-help

-

get-command

get-help

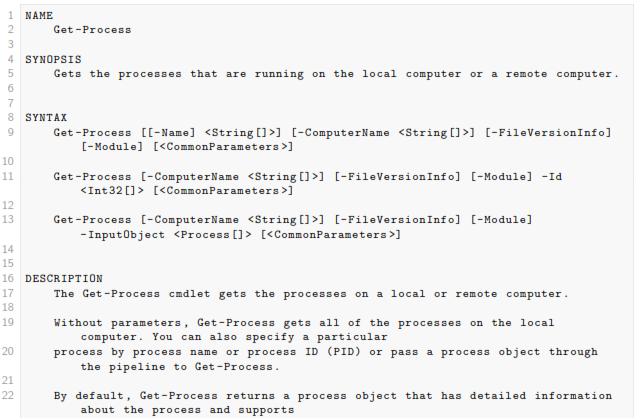

get-help is similar to the Unix man[3].

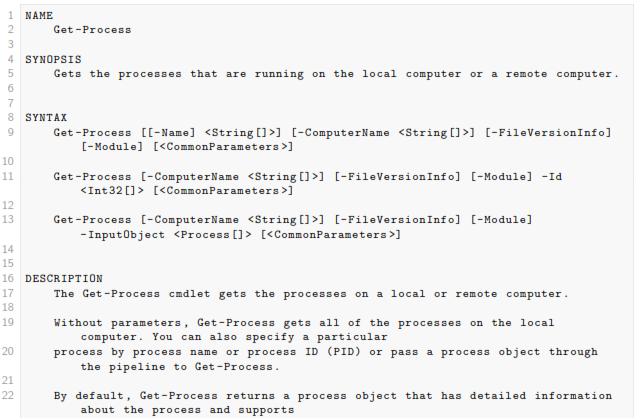

So if you type get-help get-process, you’ll get this:

There are a couple of wrinkles which actually make the PowerShell ‘help’ even more help-ful.

-

you get basic help by typing get-help, more help by typing get-help -full and…probably the best bit as far as I’m concerned…you can cut to the chase by typing get-help -examples

-

there are lots of ‘about_’ pages. These cover concepts, new features (in for example about_Windows_Powershell_5.0) and subjects which dont just relate to one particular command. You can see a full list of the ‘about’ topics by typing get-help about

-

get-help works like man -k or apropos. If you’re not sure of the command you want to see help on, just type help process and you’ll see a list of all the help topics that talk about processes. If there was only one it would just show you that topic

-

Comment-based help. When you write your own commands you can (and should!) use the comment-based help functionality. You follow a loose template for writing a comment header block, and then this becomes part of the get-help subsystem. It’s good.

get-command

If you don’t want to go through the help system, and you’re not sure what command you need, you can use get-command.

I use this most often with wild-cards either to explore what’s available or to check on spelling.

For example, I tend to need to look up the spelling of ConvertTo-Csv on a fairly regular basis. PowerShell commands have a very good, very intuitive naming convention of a verb followed by a noun (for example, get-process, invoke-webrequest), but I’m never quite sure where ‘to’ and ‘from’ go for the conversion commands.

To quickly look it up I can type:

get-command *csv*

… which returns:

Functions

Typically PowerShell coding is done in the form of functions[4]. What you do to code and write a function is this:

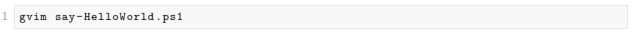

Create a function in a plain text .ps1 file[5]

say-helloworld.png

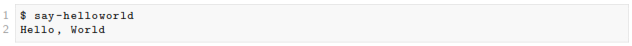

…then source the function when they need it

…then run it

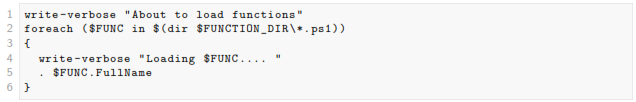

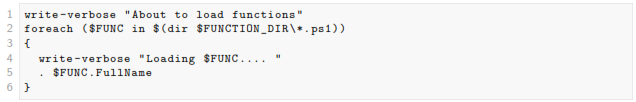

Often people autoload their functions in their $profile or other startup script, as follows:

## Footnotes

[1] If you wanted the equivalent of ls -ltr you would use gci | sort lastwritetime. ‘gci’ is an alias for ‘get-childitem’, and I think, ‘sort’ is an alias for ‘sort-object’.

[2] Another way of returning all of the properties of an object is to use ‘select *’…so in this case you could type get-process | select *

[3] There is actually a built-in alias man which tranlates to get-help, so you can just type man if you’re pining for Unix.

[4] See the following for more detail on writing functions rather than scripts: http://blogs.technet.com/b/heyscriptingguy/archive/2011/06/26/don-t-write-scripts-write-powershell-functions.aspx

[5] I’m using ‘gvim’ here, but notepad would work just as well. PowerShell has a free ‘scripting environment’ called PowerShell ISE, but you don’t have to use it if you dont want to.