CHAPTER FIVE

BETTER THAN APARTHEID?

‘I see that Fidel Castro has died. You commies from that reformatory at Wits must be distraught’ I said to Chris van Huysteen as he tucked into yet another bottle of Unbelievable.

‘The man was the greatest liberation hero since Chez Guevara you ignorant Boksburg altar boy. I respect the principles he fought for and yes I am in mourning’ said Chris.

Miffed, I countered ‘I will let all of my mates who took Cuban bullets to save your scrawny arse know. Perhaps you can then re-enact your red soliloquy when they hop in here on crutches to listen’.

‘For your information dumbass the Cubans were fighting to curb Apartheid, racialism and oppression of which South Africa was internationally guilty’ Chris asserted.

‘And where we you brave liberator?’ I chirped

‘I was in the South African Infantry in Potchefstroom for your information which was better than you cloistered away in Voortrekkerhoogte playing that sissies game – cricket’.

‘Isn’t it treason to fight for one side while believing in the cause of the other side?

You should have been arrested’. I contended.

‘You are hogging the wine’

‘What’

‘You are hogging the wine’ he said

‘Oh sorry mate, here have some’

‘So, where were we a moment ago’

‘We were at the part where you were being tried for treason whilst I was caressing shiny leather through the offside field’ I smirked

‘Military service was obligatory. I would have been tried for treason if I did not fight for South Africa’ defended Chris.

‘Man, you Wits commies were really screwed in all ways. You should have attended more cricket practices’

‘Bullshit aside Bryan, had Fidel won, you and I would now be tilling on some communist farm in Blyvooruitsig’ said Chris seriously.

‘Let’s us drink to victory over the Cubans and the unbelievable spirit in this bottle’ I suggested.

‘Seriously again though Bryan’ said Chris ‘Fidel’s legacy still lives on in South Africa. He taught the current ANC executive to appreciate Lenin and Marx gobbledegook economics which these chaps religiously still follow. If they could read between the lines they would know about the collapse of communism. Instead they still take the little red book to Parliament and try to make the Russian boot fit the African foot’.

I opined ‘If they took a peek at Smith, Keynes or Friedman they would cease to stuff the Public Sector with mushrooms in the hope that they will grow. And do not get me onto the subject of bloated Administration. We have a bigger one than the USA, which has a population five times ours. The Private Sector makes the profit, pays the taxes and creates jobs. The Public Sector receives welfare, graft, incurs losses, buys personal property and oh yes, I almost forgot, it levels the playing field for the Private Sector’.

‘Well then you Boksburg altar boy what do you suggest we do’ said Chris

‘Get another bottle of Unbelievable’ proposed I.

‘So, they really did teach you some important stuff at your Boksburg altar classes’ said the smiling Chris.

‘Waitron, another bottle of Unbelievable please’ the pair shouted in unison.

The lingering, unspoken pain of white youth who fought for apartheid

Theresa Edlman

September 2, 2015

The legacies of apartheid in South Africa can only be understood by making sense of the complexities of the past. This includes recognizing what those who were young during the apartheid era - and who are now the elders and leaders of our society - experienced during that time.

In the roughly 30 years between the Sharpeville massacre and the 1994 democratic elections that ended apartheid, a generation of Southern Africans faced challenging and often conflicting choices about ideological allegiances.

For young white boys, the end of their school careers came with a choice about responding to the call-up to the South African Defence Force. This system of military conscription was instituted in 1957 by the apartheid government and became compulsory from 1968 onwards.

The end of apartheid meant this was the last generation of white South African and South West African (now Namibian) families to send their young men off to war in such large numbers. The very different dynamics of contemporary South Africa make it hard to understand the scale of pressure these young men experienced at home, in many churches and in most social and political domains. White South African society was politically conservative and deeply invested in protecting its interests. Democratic notions such as freedom of choice were almost unheard of. Calls of duty and service were paramount.

The impact that the system of conscription had on the roughly 600,000 white men or 7.1% of the roughly 4.2 million white people in South Africa in 1992, who became both pawns and agents of the apartheid state, has seldom been publicly acknowledged in post-apartheid South Africa.

Duty and conscience

Those who accepted the call-up received rigorous military training, followed by deployment in South Africa, Namibia or Angola for the rest of their period of service. Then, after that, came several years of annual short-term camps. Over the 25 years that conscription was in place, service increased from nine months to a total of 720 days including camps.

Military combat was rare until 1975, when the SADF invaded Angola after its Portuguese colonial government collapsed. This initiated 14 years of what became known as the “Border War”, consisting of intense military and guerrilla warfare in northern Namibia and southern Angola.

There were harsh consequences for those who disobeyed the call-up. What were their choices? A court martial and up to six years in prison, exile in another country or going into hiding in South Africa.

University studies could delay military service, and some men exploited this for as long as possible. Conscientious objection (on religious rather than moral ethical or political grounds) became a legal option in the mid-1980s – around the time the End Conscription Campaign was established and began public campaigns in support of conscientious objectors as well as calling for an end to conscription.

The war comes home

White South African society lived in almost complete ignorance about the scale of the war and the SADF’s strategies. Most conscripts said little about what they experienced. This was partly because they had to sign the Official Secrets Act upon joining. It was also the result of the willed ignorance of most white South Africans and the draconian censorship laws of the time.

In the mid-1980s, anti-apartheid resistance within South Africa intensified and SADF soldiers were deployed domestically. Suddenly, young white men were being called on to police fellow citizens by patrolling the racially defined borders between segregated communities. The Border War had come home.

The unsustainable nature of the morally and economically bankrupt apartheid system became increasingly evident, even to apartheid’s leaders who initiated discussions with the then banned African National Congress (ANC) during this time.

The ramifications were widespread. The war in Namibia and Angola ended with the 1989 withdrawal of the SADF from Namibia. Namibia gained independence a year later. The ANC and other organisations were unbanned, political prisoners released and the negotiations that led to the 1994 elections got under way.

1994: A new era

Conscription was officially disbanded in 1995, as was the SADF. A new integrated army was established - and conscription slipped into the realms of silence and memory for most people. For conscripts themselves, the memories of their time in the military haven’t faded. Some have embraced the possibilities of new freedoms while others have fought to maintain and celebrate historical identities in a changed context.

There have been some efforts by the public and civil society to recognize the complexities of conscripts’ experiences, being both victims of a system and perpetrators in its name. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission held a special hearing on conscription. Increasing numbers of books about and by conscripts have been published. And several groups such as veterans, some NGOs and the Legacy of Apartheid Wars Project at Rhodes University have done some work around the issue, mostly in the form of research, public dialogues and workshops to address issues of woundedness and trauma - for conscripts and those who fought against apartheid.

However, for the majority of conscripts, the experiences that have shaped their social positioning remain intact. Most of the trauma they might have experienced remains unspoken or manifests in aggression, particularly when dealing with people, groups and situations they perceive to be a threat in some way.

As the more complex dimensions of our apartheid history begin to emerge, the healing and transformative possibilities of stories about conscription surfacing in the public domain should not be underestimated - especially as a way of making sense of our deeply racially divided society.

SA in political state of emergency

News 24 Correspondent

December 25 2016 What To Read Next

Cape Town - Archbishop Thabo Makgoba used his Christmas midnight mass sermon to lash out at South Africa’s current political leadership, likening it to living under an apartheid-era state of emergency.

“It feels as if we are back to the national pain of 1963, living under a state of emergency, imposed on us by careless and corrupt leaders who have forgotten us, stripped us of our dignity,” said the Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town in a speech prepared for delivery during his midnight sermon at St George’s Cathedral.

“People of faith need to begin asking: At what stage do we, as churches, as mosques, as synagogues, withdraw our moral support for a democratically-elected government?”

Makgoba said while he did not want to be asking questions such as these, the situation compelled South Africans to do so: “When do we name the gluttony, the inability to control the pursuit of excess? When do we name the fraudsters who are unable to control their insatiable appetite for obscene wealth, accumulated at the expense of the poorest of the poor?”

'South Africa is not broken'

He said the Church would remain defiant against President Jacob Zuma’s call that it not get involved in political matters:

“Is a President of a democratic South Africa telling the Church to stay out of politics? You would be forgiven for thinking that you had climbed into a time machine and gone back 30 years into the past, when apartheid presidents said the same thing,” said Makgoba.

“Mr President, we will ignore your call, made from the palaces of power where you and your fellow leaders live in comfort. We will lament and ask God, ‘Where are you, God, when your people are marginalised and excluded?’"

The Archbishop said that the ANC appeared at “war” with itself.

“The ruling party is crippled by division to the degree that some serving members of the Cabinet believe the President must step down,” Makgoba said while he had not called for the President to resign, he had stated that he step aside while party leaders addressed “their crisis”.

Nevertheless, said the religious leader, South Africa still had hope and confidence. “For unlike in 1963, we are a democracy, and our democracy is vibrant. South Africa is not broken. We have a sound Constitution and we have seen over this past year that we have resilient institutions.”

He said that when it came to the courts, especially the Constitutional Court, civil society, the media, whistle-blowers in government and the private sector, as well as public servants who were honest and hard-working: “They are all doing their jobs well”.

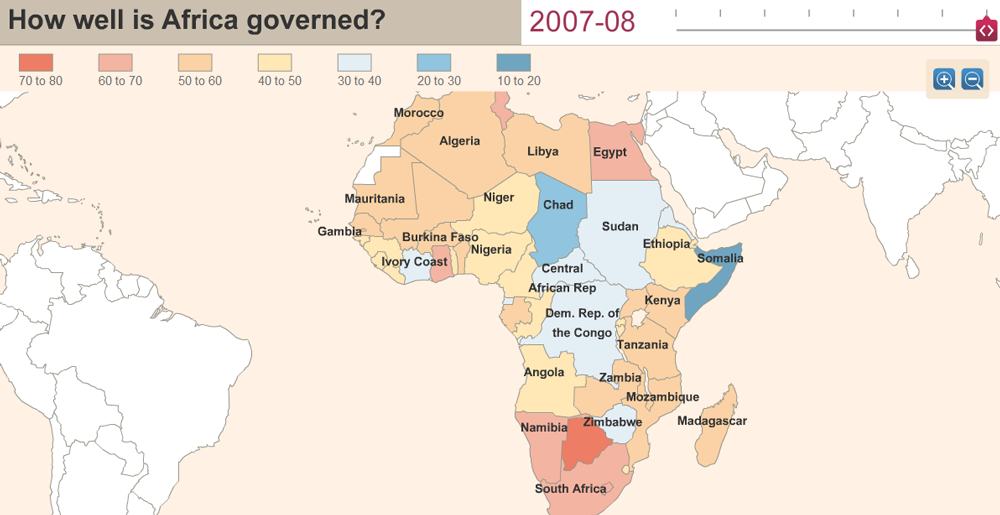

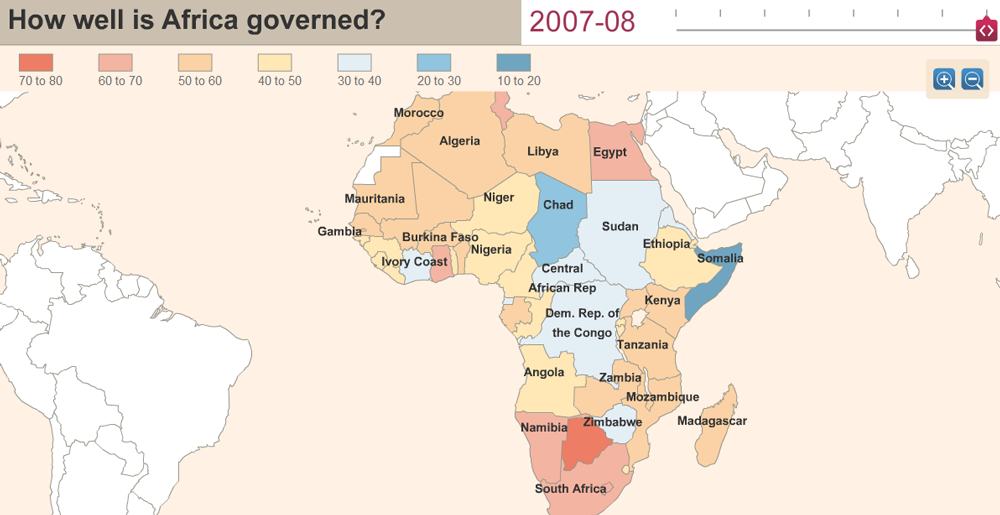

How well is Africa Governed?

Mo Ibrahim Index of African Governance

When accurate and timely information is accessible, it exposes bad practice and allows citizens to reject poor governance. Such a change brings us out of the era of Africans hanging their hopes on a nationalist leader or supposedly benign dictator. Kenya and Zimbabwe tell us that this is so; when people in these countries felt that their votes were not respected, they did not take it lying down and they did not accept it. This is a very strong message: that the wishes of African people can no longer be taken for granted. All Africans have a right to live in freedom and prosperity and to select their leaders through fair and democratic elections, and the time has come when Africans are no longer willing to accept lower standards of governance than those in the rest of the world.

South Africa has shown unfavourable governance performance since 2006, the 2012 Mo Ibrahim Index of African Governance said in a summary report on its website.

Over the past six years, it found that Egypt, Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa had declined in two categories - safety and rule of law, and participation and human rights.

“Each of these four countries deteriorated the most in the participation sub-category, which assesses the extent to which citizens have the freedom to participate in the political process.”

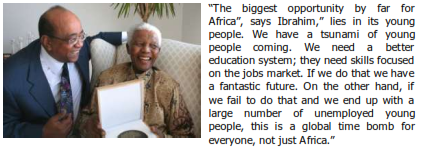

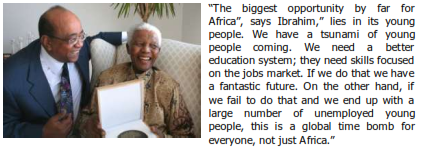

South Africa and Kenya had also registered declines in sustainable economic opportunity. It is worth repeating Mo Ibrahim’s prophetic words at the beginning of this article: “The biggest opportunity by far for Africa”, says Ibrahim,” lies in its young people. We have a tsunami of young people coming. We need a better education system; they need skills focused on the jobs market”.

When will South Africa get a Ruling Party, National Executive and Parliament that understands this dynamic and does something about it to correct the situation?

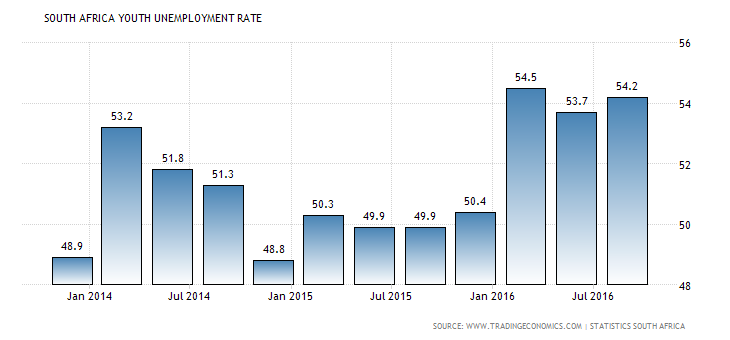

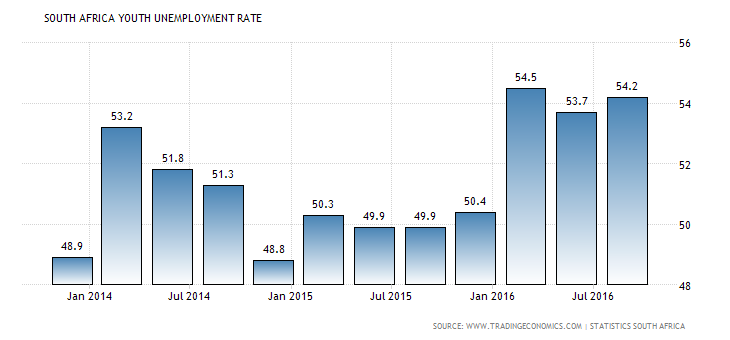

South Africa Youth Unemployment Rate 2013-2016

Youth Unemployment Rate in South Africa decreased to 47.60 percent in the third quarter of 2016 from 53.70 percent in the second quarter of 2016. Youth Unemployment Rate in South Africa averaged 51.14 percent from 2013 until 2016, reaching an all-time high of 54.50 percent in the first quarter of 2016 and a record low of 47.60 percent in the third quarter of 2016.

Before our all partying, all singing, all dancing former struggle heroes, now elite black rulers, bask too long in the sun with their snouts in the trough, you ordinary voting citizens of South Africa should point north and remind them of Africa’s shameful record of black on black oppression.

Remind them, instead of swapping war stories at the country club over claret and grilled partridge wings, to enjoin the new struggle against African elitism, against illiteracy, disease, ignorance, starvation, corruption and the moral decline amongst the youth of this country. If they do not, the next oppressor may well be from Beijing