FOREWORD

In putting this book together I have relied on the not inconsiderable skills and courage of the brave and intelligent journalists, authors, correspondents and editors of the Press. Their fight against corruption, mismanagement and criminality can only be admired and applauded. I have taken care to attribute each article reproduced here to ensure the correct accreditation to the original author of the intellectual property. If I have erred in such accreditation I humbly apologize now.

The excellent articles included are intended to be a narrative and commentary on the parlous state of our young democracy. Although these articles have appeared in the public domain it is hoped that by stitching them together they tell the story of how we as a nation declined from world famous celebrants in 1994 to our current status of tenth in the list of threats to the free world in 2016.

Rainbow stagnation

Business and the government are pulling in opposite directions on growth

Nov 26th 2016 | JOHANNESBURG

The sprawl of cranes around Sandton, South Africa’s swanky financial district, and a dearth of empty beds in Cape Town, its tourist Mecca, point to an economy that shows some signs of rebounding from a deep slump earlier this year. Taken individually many indicators are buoyant: good rains mean that farmers are likely to plant 35% more maize this year; a weak rand has encouraged a 20% jump in the number of international tourists.

Yet add these numbers up and the equation still turns out badly: the economy will be lucky to limp in with growth about 0.5% this year and will not do very much more than 1.5-2% over the next few years. This is a percentage point or two below the long-run trend rate of 3%. So what explains this black hole in the economy? The answer is almost entirely poor governance by Jacob Zuma, a president who may soon face 783 charges of fraud, corruption and racketeering.

Foolish policies play a part. Take tourism. Although the number of holiday-makers has soared, the government itself reckons that there ought to have been many more bottoms on South African beaches. Thousands have been turned away by absurdly strict rules requiring families to carry birth certificates for their children. But corruption is also hurting the economy. A recent report by an ombudsman revealed details of how the government and Eskom, the state-owned power monopoly, muscled an international mining company into selling a coal mine to friends of the president.

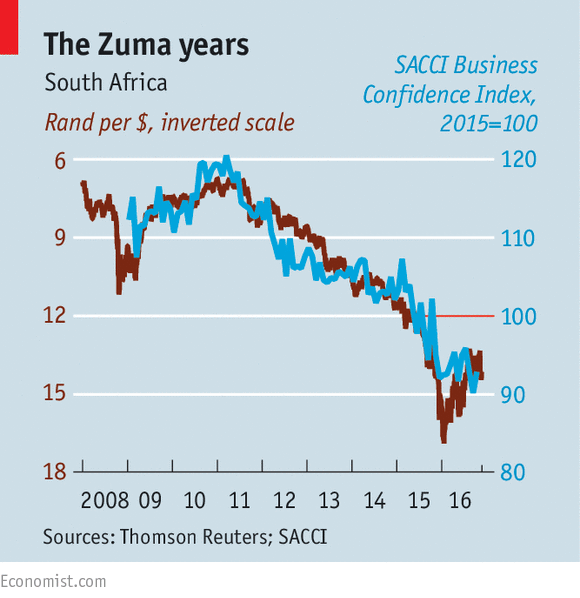

The effect of mismanagement and corruption is best seen in measures of business confidence and the currency, both of which have plummeted since the start of Mr Zuma’s presidency in 2009 . Investment has fallen to 20% of GDP from 23% over the same period.

Growth is so slow that credit-rating agencies are fretting that the country may struggle to repay its debts. Moody’s, which in May said it was minded to cut its rating, was due to deliver a verdict on November 25th. Standard and Poor’s, which rates the country’s debt one notch above junk, will give its assessment a week later. Some 80% of economists polled by Bloomberg, a news agency, expect the ratings firms to downgrade South Africa in the next year.

The threat of a rating cut is prompting feverish attempts to open up the economy by Pravin Gordhan, the respected finance minister. On November 20th the deputy president, Cyril Ramaphosa, announced a new national minimum wage of 3,500 rand ($247) a month in a bid to get unions to agree to labour-law reforms that would make it harder for them to call strikes of the sort that shut down the country’s platinum mines for almost half of 2014.

The chief executives of major banks are also involved in efforts to liberalize the economy by, among other things, getting big firms to agree to hire hundreds of thousands of youngsters on one-year internships. “In the last year South Africa’s reformist voices have been ascendant,” says Goolam Ballim, an economist at Standard Bank. “After almost a decade of political and economic drift, 2016 may yet prove to be the inflection point...in confidence and investment.” But without better leadership, such optimism is likely to prove short-lived.

Zuma’s disastrous rule goes on as a corrupt elite robs South Africa blind

Stephen Chan

November 7, 2016

A special judicial report into the capture of South Africa’s state institutions has found that President Jacob Zuma is at the very least associated with corruption, if not just as deeply embedded in it as many South Africans believe.

He never seems to learn. After the scandal of his grandiose home improvements, his unsavory association with the supremely wealthy Gupta family, and after his failed first effort to tar his finance minister, Pravin Gordhan, with dubious corruption charges, Zuma might be expected to be wary, to attempt circumspection – but he’s clearly determined not to back down, even as the political tide and South African civil society alike turn against him and his party.

The Nelson Mandela Foundation called for him to be removed from office. The opposition has been elected to take over the country’s great municipalities. Even the ANC chief whip called upon him to resign.

To add to the tawdriness, Zuma has now failed for a second time to get rid of Gordhan, whom he almost certainly regards as an obstacle to unfettered corruption. Gordhan is standing firm, which makes him a problem – although there are indications he could be hit with more corruption charges again soon.

Nevertheless, as far as Zuma’s concerned, it is business as usual. He has come up with no solution or compromise for the increasingly furious student protests roiling the country’s campuses, no plans for expanding and improving healthcare, improving the delivery of public services, and no plan for ensuring electricity. He doesn’t seem to care if the value of the rand falls because of his machinations, which serve himself and his cronies above even the ANC, much less the nation.

Slow-motion collapse

And that’s precisely the point. Zuma goes on, and knows he can go on, because the ANC itself – no matter what people say about an internal struggle – has been captured by an elite cabal of corrupt people. They have firmly ensconced themselves at the top of a trickle-down structure of corruption and patronage, one that extends to the most remote parts of the ANC apparatus in South Africa’s outlying provinces. If you want a contract for public services or delivering public goods, you have to have it sanctioned by the ANC.

All this could certainly work without Zuma, but he is simply too useful for his cronies to depose him. The corrupt elite he enables are anxious to safeguard their personal revenue-raising schemes. The president is a lightning rod: as long as he’s the focus of public attention, most of his dubious associates are not.

And so they prop up an unpopular president, one who looks increasingly silly, so they can continue go about their business – which amounts to nothing less than the slow ransacking of the nation.

Gordhan might be able to keep making a stand, and he’s no doubt trying his best. But a pebble in a river is not a dam. South Africa’s corrupt elite are too lazy for their pillage to be especially sophisticated or elusive, and in one sense, that’s just as well. But in another, it simply adds to the disaster engulfing the South African body politic and body economic.

Nobody thinks any more about modernity, internationalism, South Africa’s disappearing place in the sun. Nobody thinks of complex engagement with the rest of the world. The theme of the moment is plain and simple theft on a national scale by those who control the party and the state alike.