CHAPTER THREE

SOUTH AFRICA TODAY

In Depth: The South African conundrum – and why glass is still half-fullwhatsapp

Here’s an ideal Freedom Day in-depth read for you. Brilliantly researched and objectively written, Dr John Swart traces how South Africa got to where it is today and where the Zumafication of the nation will take it to. This is a well-reasoned thesis that ends with a surprisingly optimistic conclusion from a man whose family has felt the sharp edge of violent crime. Take the trouble to read it and you’ll be well rewarded with a more balanced perspective than you’ll get elsewhere. – Alec Hogg

By John Swart*

Since the shock announcement of the replacement of the former Minister of Finance in December last year, a wave of negativity has swept across South Africa like never witnessed before and while there has been some reprieve – brought about by a slight recovery in the SA Rand (largely driven by improved Emerging Market sentiment) and a less than favorable Constitutional Court judgment against our President, dark clouds are still hanging over the country.

South Africans, or at least those not emigrating, have developed a kind of resilience to process, accept and march on. But for how long can we carry on like this? How will it end?

Here is a snapshot of the challenges facing SA today:

-

High unemployment (26%), but perhaps closer to 40% – worst on the list of 51 OECD countries;

-

Soaring crime rates – cited one of the most dangerous countries to live in with less than 30% of murder cases solved (Institute of Security Studies – Sept 2015);

-

High levels of corruption;

-

Education levels that seems to deteriorate every year;

-

Universities in crises;

-

Ailing road infrastructure;

-

Bankrupt city councils and service delivery at worst levels ever;

-

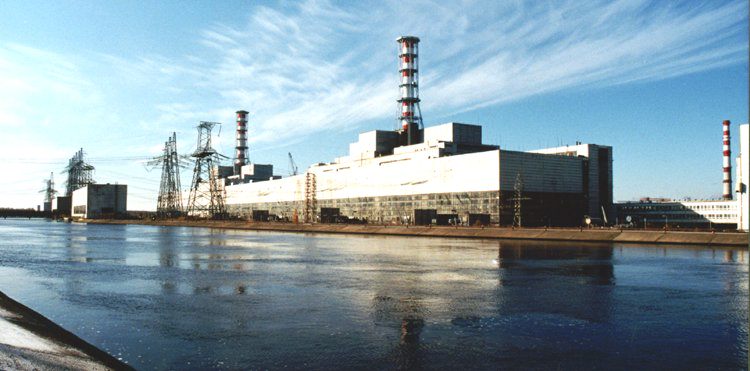

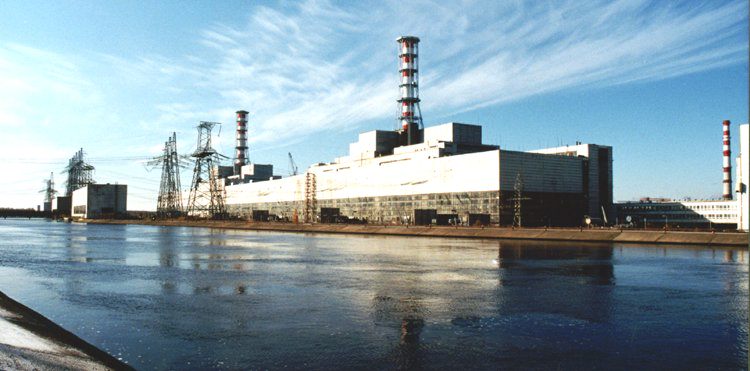

Electricity shortages stifling business and hampering growth;

-

Agriculture heading for a crisis – exacerbated by endemic farm attacks and murders (318 attacks and 64 murders in 2015 alone – according to statistics released by AFRIFORUM, a civil-rights organization linked to the Solidarity trade union), an extended period for the lodging of land claims and, currently, also one of the worst droughts in living memory;

-

Illegal immigrants that place a burden on limited resources and contribute to increasing crime rates;

-

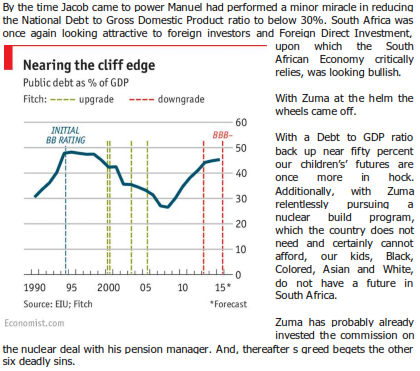

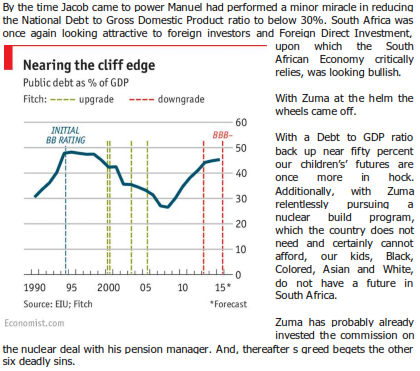

Government debt at a near record 48% of GDP;

-

The Rand at or near its lowest level against the US Dollar (losing 50% of its value over the past 5 years);

-

The worst credit rating the country has ever had – potentially facing another credit downgrade later this year which will reduce SA bonds to junk status;

-

A Government headed by a President, who is incompetent and an embarrassment to most level-headed citizens of this country and many stalwarts of his own party;

-

A small tax base threatened by higher taxes to meet growing government expenses towards a largely unproductive workforce; and

-

Rising interest and inflation rates.

-

Business confidence levels are the lowest in 5 years (RMB/BER)

For most, the so-called “Finmin debacle” that played out between 9 and 14 December 2015 and the subsequent tumble of the Rand and equity markets was simply the last straw. I realized then that it was time to take a long hard look at SA politics and economics in order to make some sense of what is happening around us; to take a position (which is imperative in my line of work); and to find ways of navigating through the portentous storm.

To assess the situation we are in, we need a better understanding of where we came from and how we landed here. To this end, I identified three distinct periods, which are best summarized by the captions selected for each such period and under which I will only highlight the most significant issues.

The sins of our fathers: 1978 – 1993

To obtain an even better understanding one actually needs to start the journey much earlier than 1978, but, due to space constraints and for the simplification of data comparison, I will only use the last 16 years of the journey towards a constitutional democracy.

South Africa was struggling to survive. Notwithstanding the gold boom between 1977 and 1980 and the massive windfall that it yielded for the South African economy, the average growth rate achieved was a very disappointing, even a measly 1.4% per annum on average, while population growth was markedly higher, averaging out at 3.6% per annum.

For most of us it is unthinkable today, but the average (prime) rate of interest was 15.95% per annum peaking at 25% in 1984 and again in 1985. The Rand depreciated at 8.51% per annum – ending at R 3.38 against the Dollar by the end of 1993.

The media was controlled by Government. The former Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) got television some seventeen (17) years before South Africa as the exposure of its citizenry to the international free-market media was considered a huge threat by the country’s erstwhile rulers.

The policy of separate development and the subsequent establishment of ten (10) “self-governing” homelands had been conceived in the mid-forties. However, it was only in 1959 that the Promotion of Bantu Self-Government Act No 46 of 1959 was promulgated to provide legislative authority for the creation of these future homelands. The Transkei was the first one to be declared independent in 1963, but due to a variety of problems and obstacles that were encountered along the way, the remainder were only established in the seventies.

The homeland policy was not only morally indefensible, but the professed objective of making these homelands self-sustainable was also proving to be hurdle too far. More than 80% of South Africa’s population was forced to occupy 15% of the land with little or no infra-structure. The true cost of how much successive South African Governments have spent in the development and maintenance of this policy will never be known, but, for present purposes, it suffices to say that it was many, many billions. The homelands ceased to exist in 1994 when South African became a constitutional democracy. At the time, more than 650 000 people were employed on a permanent and full-time basis by Government to administer these areas alone.

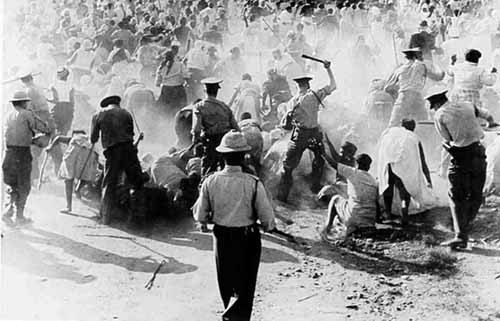

Apartheid laws forced black male breadwinners from these homelands, who were employed in mines and factories to live in poorly equipped and dilapidated hostels – far away from their families – resulting in the destruction of the very fabric of society. Poor living conditions and criminal activities in and around these hostels often left children orphaned, many of whom ended up eking out a life of misery on the streets. We are experiencing the effects of this today and will continue to do so for many years still to come.

The former South African Defence Force (SADF) cost many more billions, both in terms of its capital and operational expenditure. Years of productivity of was lost through a system of compulsory military service, where educated people, including ones with a tertiary education, were taken out of civil society to provide manpower to the SADF. This disrupted industry and hampered economic growth.

Imagine our country today, if the billions spent on establishing, maintaining and enforcing the homeland policy, had rather been spent on the education of all its citizens and other vital infra-structure development.

The Bantu Education Act No. 47 of 1953 was one of apartheid’s most offensively racist laws. The historically derogatory name of this statute was founded on the Bantu education policy invented by Werner Eiselen, a close ally and associate of Hendrik Verwoerd. Education for black scholars was disgracefully limited. By 1976, only R6 per year was spent per capita on a black child’s education, while R100 per year was spent per capita on a white child’s. Less than 12% of the annual amount budgeted for social spending, was allocated to blacks while they made out more than 80% of the entire population. Moreover, the standard of black education was lower than those of most other African Countries.

During these 16 years prior to the dawn of the new constitutional dispensation, unemployment rose dramatically from 20% to 36% of the workforce. Also, by the end of 1993, the ratio of Government debt to GDP had reached 54%.

The apartheid model might have worked well for the few (less than 20% of the population), but it was immoral and unsustainable. South Africa became isolated from the world, unrest escalated and a total economic collapse was imminent. Change was urgently required.

The Rainbow Years: 1994 – 2009

Thanks to visionary leaders such as the late Mr Nelson Mandela, the first President of the new South Africa, and Mr FW De Klerk, the last State President of the previous regime, as well as other leaders such as the late Mrs Helen Suzman, the late Dr Frederik van Zyl Slabbert and Mr Thabo Mbeki and many others (coupled no doubt with a fair amount of influence from business and foreign governments), a peaceful transition took place which lead to the first democratic election on 27 April 1994.

Under the reconciliatory leadership of Mr Nelson Mandela, South Africa was welcomed back into the international arena and huge advances were made. Under the astute, albeit possibly less popular, leadership of Mr Thabo Mbeki, these relationships were improved further. A solid financial and economic framework was established under the prudent leadership of Mr Trevor Manuel and, some years later, Mr Pravin Gordhan (both Ministers of Finance) and Mr Tito Mboweni (the former Governor of the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) from 1999 to 2009). The consequences of this framework were sound monetary policy and fiscal discipline which bolstered confidence in the country and saw the Rand doubling in value from its low in 2002 to a steady R 7.37 to the US Dollar by the end of 2009. During these so-called ‘rainbow years’ the Rand depreciated by an average of 4.9% per annum against the US Dollar, which was in-line with all Resource based economies’

Selling our children short again

By Bryan Britton

27 December 2016

By 1994 the Apartheid Government had borrowed against South Africa’s future in an attempt to uphold the untenable principle of separate development. At that time with a debt ratio of about 50% of GDP our children were faced with a future of repaying their errant parents debt well into the future.

Under the conservative stewardship of first Nelson Mandela and after him Thabo Mbeki, Finance Minister Trevor Manual was allowed to reel in excess expenditure and prudently repay the country’s debt.

I have this to say to Zuma: ‘Pay back the money’.

Selected extract from Johann Rupert’s acceptance speech at Sunday Times Top 100 Companies, lifetime achievement award

...........’The next thing is that there’s confusion between the role of government and ‘what is the state’. This has been throughout South America – throughout Africa. Our problem is governance.

If you look at North and South Korea or East and West Germany…if you go back to the 1880’s, the standard of living was the same all over the world. It didn’t matter whether you lived in Cape Town, Rio, Buenos Aires, Mexico City, London, or Paris. It was basically, the same quality of life.

We have created wealth. By the way Mr President, for all of you civil servants here – even Minister Gordhan – says, ‘we’ve got to be caring. Don’t make too much money’. I’ve got news for you. The PIC owns two-and-a-half times the number of shares in both Richemont and in Remgro that our family owns. Now remember that’s your pension fund, you may wish to reconsider the ‘caring’ bit.

Our job is to create wealth and to pay people properly, which we’ve done all our lives. Creating wealth and creating jobs, creates further jobs. We pay tax. We brought back tens of billions of Rand in foreign exchange and every year our family companies bring back more dividends than the rest of the Stock Exchange together.

You do not expect to hear these narratives, especially not when the narratives are from the Presidency and his close friends.

So the real question is, “Why?”

That you’ll all have to think about it ourselves? What is being hidden? Why attack people instead of debating the issues?

Our issues are unemployment and a terrible education system. It is a disaster. Unless we fix that, we have no hope.

Yes, Minister Gordhan, I started in 1979 a small business development corporation and we’ve created 700,000 jobs. This was done for black people living in cities who did not have the ways and means to build up capital. So I’ve been in small business.

We’ve done it since 1979. Been there done that and we’ll help again. But we really need to define the roles between business and the government and the state. This is because governments cannot create jobs. The state cannot, otherwise there’d be no unemployment anywhere in the world.

It’s the private sector that has got to create the jobs and all we need is certainty, rule of law, transparency. When there are tenders, they must be public tenders. It must be transparent.

I’ve personally never done business with the state. Really, it’s because I don’t trust the State. So I don’t know who I could have captured’.