CHAPTER 3

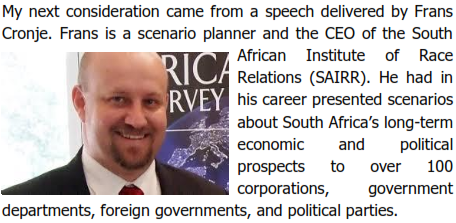

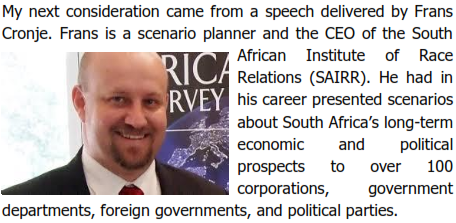

In 2007 he established the Centre for Risk Analysis within the SAIRR. He is also an associate of the South African scenario planning consultancy, the Centre for Innovative Leadership, which was for ten years the South African representative of the Global Business Network - then regarded as world's leading scenario planning group.

He delivered this particular paper to the Trans-Atlantic Dialogue Programme of the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom in Brussels on September 3, 2015.

South Africa – a failed state?

[This speech is based on one delivered via the same programme in Washington in May of this year.]

‘The title that I was asked to speak to, South Africa – a failed state, is a timely warning to the South African government of just how has swung against the country. It is a question that should never have been allowed to arise – but it has and must be answered.

For the last 40 years analysts working at the IRR have been able to speak optimistically about South Africa’s prospects confident in the knowledge that their analysis would prove to be accurate. Matching optimism with accurate analysis has become a lot more difficult.

South Africa’s socio-economic predicament is well understood. Our economic growth rate is well below that of comparable emerging markets – particularly those in Africa.

Electricity supply shortages are a crippling constraint on future growth and make it impossible, in the short term, for the country to notch up growth rates much above 2% of GDP. But economic growth at twice that rate is necessary to make inroads into our unemployment crisis. Half of the country’s young people do not have jobs.

Only half of South Africa’s children are likely to complete their schooling, while less than 1 in 10 will pass mathematics with 50% in their last year of high school.

Yet our economic evolution has been towards an increasingly high-skilled services orientated economy – in which the role of primary and secondary sectors has fallen away.

Weak economic performance is putting pressure on government revenues, which means that policies based on state-driven socio-economic advancement are ever less likely to succeed as the fiscal deficit becomes one of the most powerful forces acting on the government. Debt levels (that have doubled in a decade) exclude the possibility of aggressive borrowing.

The current account deficit has the distinction of being the widest of any country tracked weekly in The Economist. The current commodities blow-off has left South Africa’s export economy even more exposed – and we do not anticipate a commodities recovery for quite a number of years.

Yet the manufacturing economy has been decimated over the past 20 years by rising costs and unwise labour policies. The domestic consumer confidence index – which drives household spending equivalent to 60% of GDP - is plumbing decade deep lows. Household debt levels have escalated by 30 percentage points over a decade while in recent years secured lending has flattened as unsecured lending levels trebled.

We see increasing evidence of investors getting out of South Africa. Rising and unmet expectations are now driving violent protest levels that have grown by more than 100% over the past decade as government popularity turned downwards.

Voter turnout has fallen sharply and more people now choose not to vote than those who support the ruling party. To complicate matters the South African government has adopted a peculiarly virulent anti-Western – and anti-European - foreign policy. Threats against the free media, the judiciary, and civil society are all escalating as the political temperature increases.

We are, of course, not a failed state – I can say that with complete confidence at the start. But if state failure starts somewhere then the combination of forces I have described above would be as good a point as any. As a colleague suggested to me yesterday if you want to make a failed state then we now have many of the ingredients. Arguably, then, at worst, we are in the embryonic stages of state failure. The question is where do we go from here?

The answer will depend on the extent to which our current socio-economic predicament is exploited by a clique of powerful politicians who have effectively hijacked the policy formulation process in our country in order to place South Africa firmly on the route, first to socialism, and then, to quote from the South African Communist Party, which now commands 4/10 Cabinet seats, eventually, “a fully-fledged communist society”.

How did this unfortunate state of affairs come to pass?

In 1991 Nelson Mandela returned from Davos convinced that the world had changed and that the Afro-Socialism - once espoused by his party - needed to be rejected in favour of a new, better, economic policy direction.

That thinking led to the drafting, first of the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) policy blueprint in 1994, and then the Growth, Employment, and Redistribution or GEAR policy in 1996 which became the mainstay of much South African economic policy thinking for the next decade.

Both policies, GEAR especially, were conservative policies that emphasized the importance of economic growth and fiscal consolidation – as well as sound relations with Western powers.

These policies saw interest rates more than halve between 1994 and 2007, the debt to GDP ratio was brought down from 48% to the 20 percentiles, economic growth steadily escalated to average over 5% of GDP between 2004 and 2007, and six million net new jobs were created. In two years the South African government was even able to show budget surpluses.

Such liberal conservatism came under considerable pressure from remnants of the leftist and communist factions of the African National Congress. But Mandela was resolute on the importance of South Africa adopting a pragmatic economic policy framework. He personally drove considerable efforts to isolate communist influences within his party – a role later played by his eventual successor Thabo Mbeki.

In addition higher growth rates, significant early job creation, an expanding tax base, and declining debt levels allowed the government to implement one of the most expansive social welfare systems of any developing economy.

While we were critical from the start of the dependency this bred we have none the less repeatedly acknowledged the significant improvements that accrued to the living standards of poor people

On balance during its first 15 or so years as a democracy South Africa was showing many of the signs that its political transition of the 1990s would, despite stumbling blocks, see the country emerge as a leading emerging market.

However, over the past seven years things have gone very badly wrong. At a policy conference in 2007 leftist factions within the ruling alliance staged a fight back and deposed President Thabo Mbeki.

That policy conference was the beginning of a purge, and later isolation, of the ANC’s pragmatic generation of post-apartheid leaders. Their places have been filled by hard-line communists who now exercise a considerable degree of influence over economic thinking.

This new leadership has wasted no time in seeking to change South Africa’s policy trajectory. It has sought to undermine the private sector, isolate the country from Western interests, and erode its democratic institutions.

Indeed earlier this year a senior communist leader suggested that South Africa should uncouple itself from the global economy. Just last month the ruling party issued a scathing, even hateful, denouncement of Western democracies – something that should be of great concern here in Brussels as the implications for your long term interests in Africa are likely to be so significant.

One prominent example of the new policy trajectory is the Private Security Industry Regulation Amendment Bill of 2013 which will require all foreign-owned security companies to have 51% South African ownership. This may herald the beginning of broader indigenisation requirements, as in Zimbabwe.

The Economist saw the risk early on when in quoted us faithfully that South Africa had “moved quickly to adopt laws and policies that weakened property rights, reduced private sector autonomy, threatened business with draconian penalties, and undermined investor confidence”.

Though such statist intervention is clearly proving harmful in practice – just look at our economic indicators - it still enjoys considerable support among key opinion makers.

In our engagements with civil society organisations and journalists, we regularly confront influential people who spend a lot of their time advocating for ways in which the state can exercise greater control over the lives and futures of individuals, businesses, and other organisations. Perversely such policy may become even more entrenched as the economy weakens.

The danger is not just in the economic sphere. Rather the consequences of declining economic freedom have already been exploited to drive a resurgent racial nationalism that argues for rights and freedoms in the Constitution to be eroded in order to liberate the poor from oppression. As a result our democracy is in trouble.

We have warned at length about growing political manipulation of agencies and institutions ranging from the police, to the revenue service, the national broadcaster, the public protector’s office, and the human rights commission. The judiciary regularly faces unfortunate political criticism. In fact every democratic institution is being eroded where it demands political accountability or investigates official malfeasance.

The free media faces hostile regulation and many newspapers are heavily dependent on government advertising, which could now be withdrawn from those identified by the government as too critical and “negative” in their reporting. Some have already published sycophantic pieces of appeasement designed to win favour with South Africa’s political elite.

Also worrying is the growing brutality of the State. We have warned against the high number of torture cases being brought against the police. In time, we said, such methods might be used not only against criminals but also against the Government’s political opponents.

Popular demonstrations are regularly suppressed and activist leaders intimidated by the security forces. Many civil society groups and think-tanks (although not ourselves as we are almost exclusively domestically resourced) rely on foreign funding which if restricted will greatly undermine civil society activism.

This analysis might seem too strong to some. However, not even the sanctity of Parliament was respected when riot police entered that house to eject an opposition member who had described the President as “a thief”.

Weeks later a police contingent disguised as parliamentary stewards would evict an entire opposition party from South Africa’s state of the nation address after party members engaged in aggressive heckling that forced the President to interrupt his speech. We now have a government whose security forces shot and killed over 30 protesting mine-workers but three years later has as yet to hold any official to account.

Don’t be fooled by the South African government’s protestations or purported renewed commitment to the National Development Plan (NDP) – its latest policy blueprint. In the hands of the current Cabinet this plan may turn out to be little more than a smokescreen for another agenda.

Our sense, based on 80 years of experience in South Africa, is that a single overt move to drive the country into socialism overnight, seize all private assets, and destroy all democratic institutions remains less likely than a continued white-anting of constitutional protections for property and other rights as the economy stagnates.

This continued decline is our most likely scenario. If the electoral system remains intact it may culminate in a defeat for the ruling party, triggering a new era of coalition politics.

The likelihood, however, is that the political leadership will seek to destroy democratic institutions to cling to power by any means.

If we are to turn the tide we must exploit the window of opportunity that exists in South Africa’s current economic crisis and dedicate ourselves to shifting public opinion away from dirigisme and towards the economic freedom vital to investment, growth, and jobs. We must also keep showing that economic and political freedoms are two sides of the same coin. Given the essential link between the two, the diminution of economic freedom now well in train will in time also reduce the political freedom secured in 1994.

If we can be successful in advocating for reform then there is a second scenario in which a future South African government, under incredible political and economic pressure, adopts market driven policy shifts and a multi-polar foreign policy in a bid to secure the investment to drive the growth levels to create the jobs to meet popular expectations while reducing the triple (household, current account, and fiscal) deficits.

While we assign a degree of plausibility to this, better, scenario the latest policy documents published by the ruling party still remain hostile to property rights and private investment. Equally much of civil society and the media remain ideologically hostile to market reforms while business leaders are seeking to diversify out of South Africa and Western diplomats seem unsure about how to respond to the rapidly changing climate.

Certainly they are doing very little to advance reforms. For our part we are not going to die wondering what might have been. We are working very hard to build a groundswell of public, official, and political support for policy reform in order to safeguard property rights and the rule of law, adopt market driven reforms, and thereby position our country as a leading emerging market on the continent’.

I rationalized ‘To change the voting system, revitalise the traumatized institutions, dissuade the cognoscenti from leaving and re-motivate the Private Sector would entail a lifetime’s work’.