Why the Government Prints Money

It doesn’t take a Ph.D. economist to realize that simply printing more money is not a real solution for getting out of debt. Surely, the Department of Treasury – many of whom are Ph.D. economists realizes this as well.

According to the Bureau of Printing and Engraving, in 2014 the United States printed approximately $560 million every single day. That’s $204.4 billion printed in 365 days. That may seem excessive, yet the U.S. Department of Treasury states that approximately 90% of the money they print is made to replace notes that are taken out of circulation, however, there is currently $1.4 trillion circulating in the Federal Reserve. That leaves us with a meager $20.4 billion going into the Federal Reserve annually.

The government likes people spending money. In fact, the economy depends on it. More cash flow helps businesses grow and allows them to compete with other domestic and international businesses. This healthy corporate competition breeds ingenuity and development. Most of the time this makes the consumer’s life easier, like when a business comes out with a helpful new gadget or technology. Sometimes, it makes our lives worse, like when that money is spent on destructive marketing campaigns. Yet, the government needs to print money in order to keep the economy moving at a steady pace.

Another reason the US creates more than $20 billion every year is because of the increase in population. According to the Center for Disease Control, there are about 4 million babies born in the US alone each year, and 130 million newborns around the world, according to the World Health Organization. In the government’s eyes, each newborn baby that comes into this world is a new mouth to feed and a new customer.

As a rule, inflation occurs when demand is higher than supply. A good example of when the demand for something far exceeds the supply is on Black Friday. Customers line up outside of stores huddled together in the cold – sometimes camping in front of stores for days – just to save a couple of hundred dollars on a new TV or Xbox. Yet the store is only supplying a handful of customers with those products at that low, low price, despite many customers who demand them. The result is chaotic, unruly, and often violent. As we have witnessed on

economy in which the demand far exceeds the supply of goods is not only unstable, it brings out the worst in humanity.

In the case of inflation, however, businesses will raise their prices to exorbitant amounts when they know that there is a large demand for their product that is in short supply since they know that people are still willing to pay for it.

Alternatively, when the demand for products slows down, so does the economy. Although the government continues to print money, employers are laying off their employees because they aren’t getting enough business. In periods of low demand, such as in the Great Recession of 2008, no one makes money.

So, while the government printing a moderate amount of money can be a good thing for the economy (depending on the rate at which they are simultaneously removing currency from circulation), when more money is printed than is being spent, it can have disastrous consequences for not just the economy of that country, but the world. What’s worse is that there is no clear formula for how much money should be printed in a given year; it’s really more of a trial and error situation.

The terrifying truth is that, when you look at examples of hyperinflation throughout history, they almost always happen during times of political instability and war. For example, it was the mass unemployment of the Great Depression that led to the rise of the Nazi Party, who was insignificant during the Great Hyperinflation.

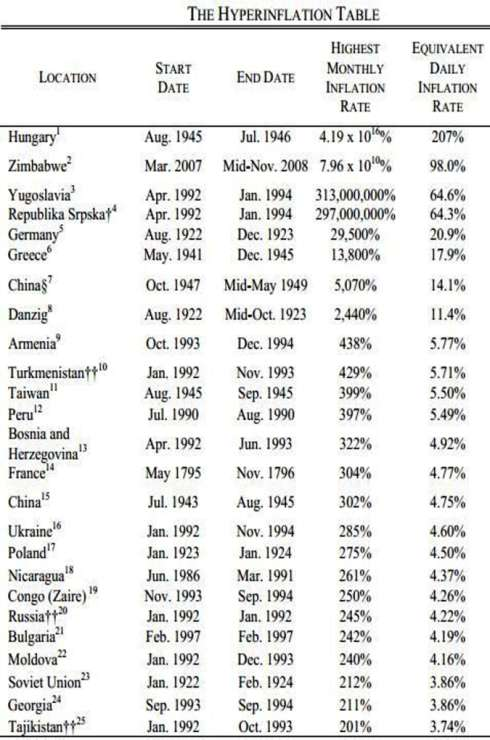

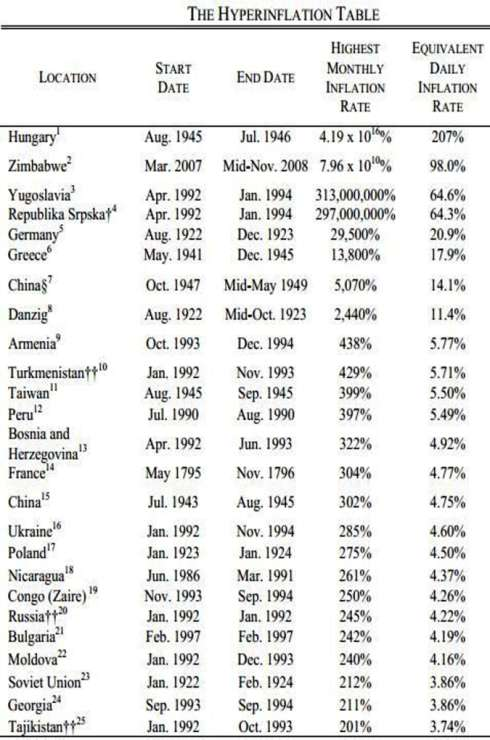

The chart on the next page lists the worst hyperinflations in history and it is clear that almost all occur when the state was on the verge of collapse, mostly around the time of the First and Second World War and the collapse of the Soviet Union. Zimbabwe is the main exception in that it wasn’t at war, though it was very politically unstable.