HOW TO USE THE MINDMAP

What is it?

Knowledge consists of concepts available to process information and guide action. The core concepts of human knowledge are depicted in a series of lists organized as a MindMap. As Tony Buzan (THE MINDMAP BOOK, BBC Books, London, 1993), the inventor of the MindMap concept explains, this display technique gives a graphical integration of knowledge that words alone cannot provide.

How to use it?

Read the book through once - it is short, modularized, and will provide a sense of the content of the message, and of how it is presented. Using reference sources on any topics under consideration will also likely prove helpful; then apply the concepts and consider the implications henceforth.

Who should use it?

Anyone whose job requires knowledgeable processing of information (students, intellectuals, support staff, managers, service staff, professionals, operational staff, experts, etc.) will find the MindMap useful. It enables a person to sort experience into conceptual categories, the basis of thinking. Every situation can be ‘deconstructed’ into the concepts on which it is based or which it incorporates. You can use the MindMap construct to explore situations, or find issues elsewhere and assess them with MindMap concepts.

What are the implications?

The core premises for the design of the MindMap are Conceptual Pragmatism and Cognitive Economy i.e., our ideas should have maximum use-value and minimum complexity. The concepts in the MindMap allow the user to triangulate the issues that are involved in whichever situation is encountered. If your question is "How do I know?" then it will involve some combination of elements of empiricism, rationalism, and constructivism. Such cognitive amalgamations do what makes "knowing" possible; other aspects of experience can be deconstructed and reconstructed just as readily using the MindMap.

Once concepts are identified and categorized, what then? In the process, one often finds that issues appear incommensurable because the ideas on which they are based seem incompatible. In such cases, there are three ways of negotiating commensurability: (a) reduction (to a common standard, i.e., money, energy, votes, etc.); (b) separation (into distinct dimensions/judgments, i.e., beliefs, values, preferences, etc.); and (c) innovation (synthesize an encompassing alternative, i.e., bisociation , lateral thinking , thunks , etc.).

Innovation has the highest commensurability potential.

References

1. Conduct an Inventory of Your Own Cognitive Processes

In Systems Analysis, the place to begin a project is to inventory the existing arrangement(s) that you are trying to improve or replace. The same principle applies to adopting or improving your own approach to personal knowledge management.

(a) as you read through the outline of each concept in the MindMap, note when and how you currently use that concept, AND how you might revise or extend its use in the future – if it’s empiricism (see section on Epistemology), do you get and assess the relevant facts about a task before moving on “to do something”? Could you do better in this respect in the future? If it’s behaviourism (see section on Ontology), do you clarify “how people do things” in the relevant context before assuming you know what is and is not acceptable? Could you do better in this respect in the future?

(b) in the description of each concept in the MindMap it will be possible to formulate similar questions about how you presently might (or might not) use it, and what you could do to either begin to use it, or to more effectively use it in the future. The goal is to begin monitoring yourself on what concepts you engage when you begin to think, AND to prompt yourself to either start to use the relevant concepts or to use them more effectively.

2. Conduct a Similar Inventory of Incoming Messages

Other sources of information are NOT, in all likelihood, monitoring the use of concepts as described above. So, incoming messages will likely have large conceptual gaps in them, which is something you should also notice and monitor.

(c) messages can be interpreted as “information packets” that function to persuade you of something – some facts, or principles, or propositions, or proposals or whatever. The questions to ask yourself are: What is the topic of persuasion? How is the persuasive case being made (what evidence is being presented)? What evidence is NOT being presented that is, nevertheless, relevant?

(d) the aim here to is to track the persuasive intent of the incoming messages, so as to discern any shortcomings and/or hidden agendas. If the messages contain misinformation (insufficient evidence) or disinformation (incorrect assertions or assumptions), and they may very well, then the next question is, Does it matter? That is to say, are there egregious errors that should be and can be confronted? “Speaking out” may or may not be feasible, but it is good practice to be on the alert for deficient messaging so that you will be able to recognize it and take appropriate action when that is necessary.

3. Audit Your Inventory to Clarify Your Thinking

Reflect on your cognitive inventories to see if your thinking is (i) comprehensive; (ii) coherent; and (iii) consistent – use the MindMap for comparison. Decide which parts of your thinking you could work on, and make some effort to align your conceptual framework so that you develop a more effective capability for processing information and guiding action.

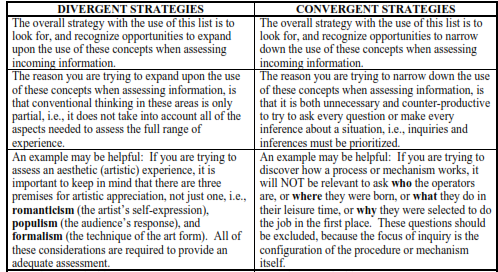

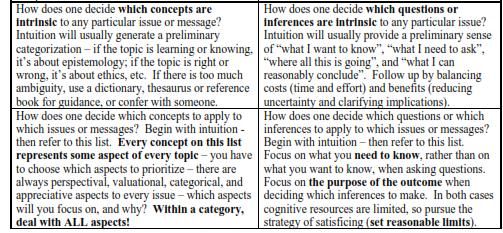

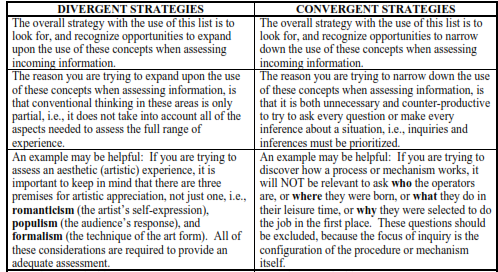

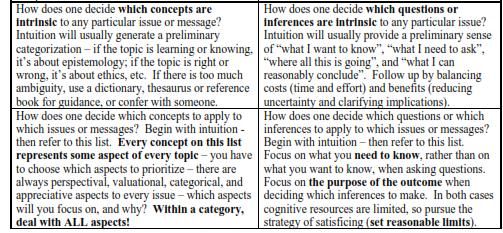

A Generic Strategy For De-coding Issues and Messages

All of human culture is written in code – this is the conclusion of Structural Anthropologists based on their numerous case studies of all types of cultures throughout the 20th century. The “code of culture” consists of deeper semantics and pragmatics than are apparent based on a simple interpretation of the explicit meaning of the signs and symbols that are communicated. The purpose of the Human Knowledge MindMap is to crack that code. The Human Knowledge MindMap can be divided into two columns (recall Ben Franklin’s technique), with the concepts on the left (Perspectivity, Methodology, Axiology and Semiology) labelled Divergent Strategies, and the concepts on the right (Quintessential Questions and Inferential Operators) labelled Convergent Strategies.

What is the larger purpose?

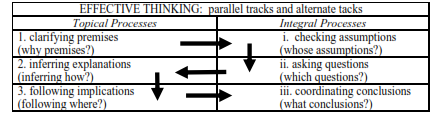

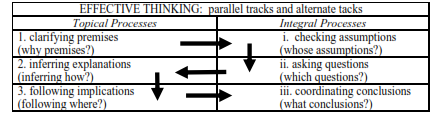

What can a user of the Human Knowledge MindMap expect to be able to accomplish that would otherwise not be possible? That will be the capability to THINK EFFECTIVELY. Most peoples’ thinking, most of the time, is not clear enough, focused enough, or systematic enough to perform “knowledge work” competently. The purpose of the Human Knowledge MindMap is to give users the wherewithal to do exactly that. Whether during education, or on a job, effective thinking consists of a set of components as depicted below.

The Topical Processes are applicable to the subject matter under consideration. The Integral Processes are intrinsic to the thinking activity itself. What effective thinking requires is tacking back and forth between these parallel tracks so that both sets of considerations are covered in the larger endeavour. The elements to do this are available in this document.

This Human Knowledge MindMap document has been written to cover appropriate sets of assumptions, questions, premises, and inferences, together with the implication and coordination techniques that are needed in thinking. The pages taking the user through this material are organized in a particular sequence, although the reader may read the material in any order. For the practice of EFFECTIVE THINKING the requirement is to go through the topical and integral processes comprehensively.

Here too, there is no necessity order in which to do this. One may encounter, contrive, or be assigned a concept, problem, or situation to which any one of these processes may be applied to begin with, but regardless of the starting point, all of the other processes have a contribution to make to the eventual outcome. The arrows in the table above suggest one sequence through the thinking processes, but the order can be varied to fit alternate styles of thinking, different individuals, and changing circumstances. The contrast to the sequential approach might aptly be called "The Pinball Methodology" - bounce the concepts and constructs around until you create an effective ensemble - history confirms that it works!

References

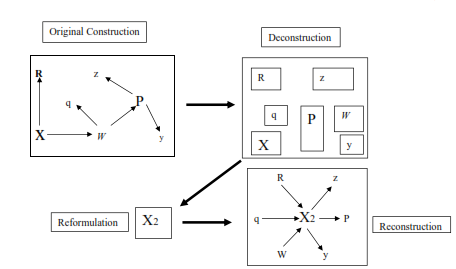

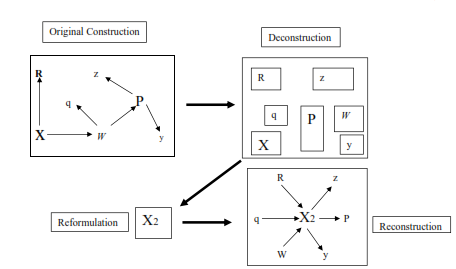

MindMap Methodology: Concept R&D

As encountered in messages from a variety of sources (conversation, text, etc.), a construct may consist of several concepts, related to each other in a variety of ways, depending on the context. Various views may be vague, or inconsistent, or both. Deconstruction consists in separating and clarifying each of the component concepts as to their individual etymology and their pragmatic use. One (or more) of these concepts may then be reformulated to enhance its inclusiveness, exclusiveness, range, or whatever. Whereupon this newly reformulated concept may then be used as a basis to reassemble the entire construct, but in a way that brings new order, generality, explication or whatever to the entire ensemble of ideas.

This idealized version presents the process as a somewhat formal, public sequence - however it can just as easily occur informally and intuitively in the mind of a practitioner. In either case the process is an art rather than a science. The definitions in the deconstruction phase may be as wide or narrow as the practitioner prefers, the choice as to which one(s) are to be reformulated is also up to the practitioner, as is the configuration of the reassembled construction. Two different individuals or groups, using the same original construction, may then settle on alternate definitions, reformulations, and reconstructions, yet be entirely correct within the logic each has employed. Good craftsmanship requires only consistency and transparency.

Application of Concept R&D

Read the entire Human Knowledge MindMap through once.

Pick a situation, problem, challenge, decision or choice of interest or concern to you (on whatever basis you regard as appropriate). Then proceed with the following steps:

1. Identify which aspects are of most interest or concern to you.

2. Prioritize (rank) your interests or concerns.

3. Using the Human Knowledge MindMap as a visual guide, apply the relevant concepts to the most important (prioritized) aspects of your interest or concern (limit it to the top three aspects on your list to begin with).

4. If you don’t recall whether or nor a particular concept is relevant, refresh your memory by re-reading the one-page outline.

5. From this point apply the methodology as outlined above (this may, in addition to other things, require reading more materials to acquire the necessary depth of understanding in the issues you are trying to deal with).

Initially this may be a slow and somewhat cumbersome process. Learning to think by applying the right tools to the right circumstances often is an initially slow process! With practice however the process will become intuitive, and you can begin to use the MindMap for periodic refreshment, and to plan for some more in-depth study of concepts, if this interests you. A good way to proceed with this more expanded goal, is to read the reference books mentioned in each of the concept pages, and then begin using your new insights to find additional materials, and/or to apply your accumulating schemata to what you read or otherwise find. Do not regard any of the references suggested as being "the gospel" on a topic - each is simply recommended as "food for thought".

Concept R&D is a dynamic process, but the key to its successful use is to recognize that the responsibility for the dynamic aspect of the process lies with the user. The MindMap can inform a user about the conceptual basis of knowledge, and about the way in which it can be most appropriately utilized. BUT, you gotta really wanna! If your interests in, or concerns with issues are not sufficient to motivate the cognitive effort to master and apply the Concept R&D methodology, then this MindMap is not for you – you will be wasting your time with it. If you decide this effort is worth your time and attention, this MindMap should be helpful. If you think that you can do any of this better than what you read herein, prove it - do it!

Universal Disclaimer: Firstly, the author of this material is not responsible for motivating users to want to think – that is their responsibility. Secondly, the author is not responsible for any action whatsoever that users may take based on what they regard as the implications of this material. Users must always take responsibility themselves, not only for deciding whether or not to think, but also for choosing what action to take (or not to take). The one claim which the author does make irrespective of any situation or user, is that being a knowledgeable decision-maker or choice-taker is ALWAYS better than being an ignorant one!

References