Chapter 10

Add Style To Your Conversation!

Throughout history, there have been men and women who, through conversation and public speaking, have been able to not only captivate the hearts of others, but attract the masses with creative speech. Those speeches influenced, motivated, drove and inspired others… To never know that words alone could produce such power. In this chapter, we review a host of techniques that may be used to turn ordinary conversational speech into something more…

Active & Passive Voices

Active and passive voices are methods of making a phrase or sentence appear more exciting or action-oriented., or less exciting or action-oriented.

Active Voice

In the active voice, the subject is performing the action (the verb). The subject could be a person or an object or a place. The subject is always disclosed before the verb (not after it). The active voice often provides an incline in emotion as it is heard. An example of active voice would be:

“John quickly opened the door.”

In the above example, “John” is the subject. John performed an action (he opened the door).

Passive Voice

In the passive voice, the subject is not the one performing the action (the verb), rather the action is being performed to the subject (someone or something is performing the action). The action (the verb) is written before the subject. The passive voice is best used when the action or verb is more important than the subject, and a lack of dynamics is required and often provides a decline in emotion as it is heard.

Compare the following sentence to the one used above in the active voice:

“The door was quickly opened by John.”

You’ll find the focus of the statement was moved away from John, and here (in the passive voice), the focus in put on the fact that the door was opened, not on the person opening it.

Passive voice is a wonderful tool to aid in removing blame… Instead of saying “I turned it on and it broke”, you can move blame away from you by saying “It broke when I turned it on”. In the first statement it appears that the method in which “it” was turned on is the cause of it breaking. In the second statement, the fault is made to appear like a mechanical problem, and “it” would have broken regardless of how it was turned on.

Emphasis

We’ve spoke a bit about emphasis throughout this book… But what exactly does it mean to add emphasis to a word? Well… Emphasis is created by altering the normal sound of a word in some fashion. This can be done by changing the dynamics (volume and ambiance), the tonality, or the inflection (pitch) of your voice when speaking that particular word. Emphasis may also be added by speaking words in an elongated fashion, or stretching the spoken word out.

Why would we do this? Good question… Adding emphasis to a particular word within a phrase or sentence causes the listener, whether consciously or unconsciously, to become more attentive to that word, or possibly even to focus on that particular word. By getting the listener to focus on one particular word within a sentence, the remainder of the words within that sentence become de-emphasized, or appear less important. This in turn causes us to believe that the emphasized word has some type of significance.

In the sentence above “The door was quickly opened by John”, we can emphasize one word – such as “was”, and now the sentence “The door was quickly opened by John” appears to declare a fact… It certainly was opened by John, there is no doubt about that!

# NOTE: In most cases, when using statements, emphasizing a word will change that word into a declaration. However, that may not always be the case. As you speak, consider how the emphasis on particular words alters the impression of the words/phrases you use.

Verbs

The use of the right verbs can make a drastic difference in how your communication is accepted, interpreted and understood. Verbs not only tell the listener what happened, but how it happened.

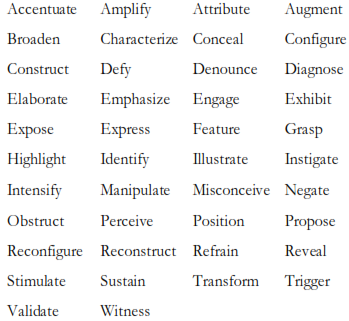

Action Verbs

Action verbs show the subject of the sentence performing some action. This can be very powerful when used in the right context. While regular verbs are used in our general everyday conversation, action verbs (often synonyms of regular verbs) are used to add more excitement, dramatic appeal and/or illustration.

Consider, for example, the difference between the following two sentences.

“He worked night and day to finish the task”.

“He slaved night and day to accomplish the task”.

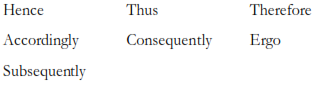

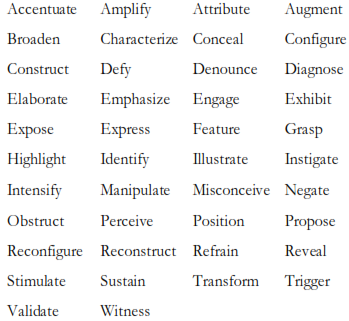

As you can see, there is a difference between “working” and “slaving”; as there is between finishing something and accomplishing something (accomplishing suggests some gain afterward, while finishing simply means it has been completed). The use of the action verbs “slaving” and “accomplishing” make the statement more emotive. Below is a short list of action verbs:

Let’s transform an ordinary every day sentence using some of these action verbs: Instead of saying

“You can do one thing and become good at it, or you can do many things and become great”… You could say

“You can focus on one area and highlight how good you are, or you can engage in a multitude of skills and broaden your horizons to reveal your own greatness”… I like the second one better, don’t you?

State-of-Being Verbs

These are usually some state of the verb “is”; they literally describe a state of being. Such verbs are less powerful than action verbs, and are often used to precede another verb. These include:

You can use state-of-being verbs to add extra emphasis to the fact that something is being done. When doing this, be certain to stress the state-of-being verb. For instance: “We are studying for the test”.

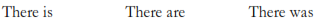

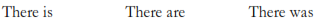

There/It Introductions

Beginning a sentence with the words “there” or “it” followed by a state-of-being verb, is generally not recommended. These types of sentenced introductions only postpone the beginning of the actual sentence, thus complicating the sentence without cause. Below is a short list of these introductions:

The following are two examples of There/It introductions, including both faulty and correct methods of beginning a sentence:

1a) Faulty: There was a chapter in the book that described verbs.

1b) Correct: A chapter in the book described verbs.

2a) Faulty: It is a perfect beginning to a wonderful story.

2b) Correct: The beginning of the story is wonderful.

Descriptive Language

Descriptive language is the use of words that help build mental images in the mind of the listener. These mental images help the listener to form a better picture in their mind of the ideas that you wish for them to understand, and when successive imagery is created, you may even form a sort of motion picture in their minds… The better they can form these pictures, the more involved they will be as a listener.

Descriptive language makes use of words that evoke the senses (sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch); as well as the emotions and state of the listener. It makes use of adjectives and adverbs. Action verbs may also be significant to the overall meaning of a phrase or sentence. Read more about this below:

Adjectives

Adjectives are words that evoke the five senses. They describe nouns (people, places, things, etc.) or pronouns (generic words that can take the place of a noun – such as he, she, they, it, each, somebody, etc.).

1) Sight: Use words that tell above colors, shapes, and sizes. For example:

“The ugly car was big and blue, and also box-shaped”.

2) Sound: Use words that describe the type of sound (i.e. crash, thunder, bang, etc.), and degrees of volume (i.e. loud, soft, ear-threatening, etc.). You may also use words that tell about the result that occurs from the sound. For example:

“She yelled at me so furiously as to deafen me forever”.

3) Smell: Use words that describe scent (i.e. “the smell of roses”); or the strength of the smell (i.e. strong, faint, bear, etc.). For example:

“Her perfume faintly smelled like wild roses in the cool breeze.

4) Taste: Use of words or phrases that describe flavor (i.e. sweet, sour, spicy, etc.), or potency (strong, weak, bland, etc.).

“The sweet taste of chocolate melting in my mouth was a godsend on this tiresome day.

5) Touch: Use of words or phrases that describe textures (i.e. smooth, rough, soft, etc.), and temperature (hot, warm, cool, cold, etc.).

“I felt her rubbing her hand upon my back so as to sooth my cough.”

6) Emotions: Use of words that describe emotions (i.e. happy, sad, excited, lonely, etc.).

“I was ecstatic to see how well you was progressing, you have really been improving well.”

7) State of Being: Use of words that describe the state of a person or thing (i.e. tired, bored, crazy, etc.).

“I’ve been persistent in my learning, but now I am very tired and need some R & R.”

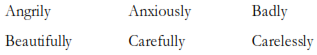

Adverbs

Adverbs are words that change or modify the meaning of a verb (an action). Although they may be suited to modify other words, they are most commonly used with verbs. Adverbs provide additional information that not only change the notion of the entire phrase, but also place more attention on the verb. Consider the following two phrases:

“He worked swiftly.”

“He worked slowly.”

In the two sentences above, the adverbs “swiftly” and “slowly” modify how the person ran. In the context of the overall sentence, this can make a dramatic difference… “He worked swiftly to get things done on time”. You can see how this is different than simply stating “He worked to get things done on time”.

When combined with intensifiers, adverbs increase their effect… Compare the following statement to the one above: “He worked very swiftly to get the job done”.

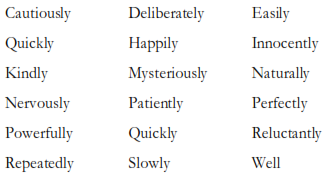

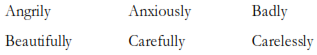

Manner

Adverbs of manner describe how something is done/performed. The adverb should normally be placed behind the noun or object of the sentence (i.e. “He placed the box [object] carefully [adverb] on the shelf”). Below is a list of some adverbs of manner:

# NOTE: Adverbs of manner are well suited to emphasize a statement, adding additional power to the verb they modify.

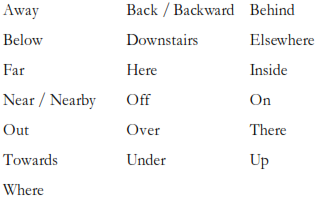

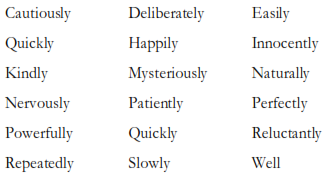

Place

These are adverbs that describe location. As with adverbs of manner, these should be placed behind the noun or object of the phrase (i.e. I don’t see the car [object] anywhere [adverb]”). Below is a short list of adverbs of place:

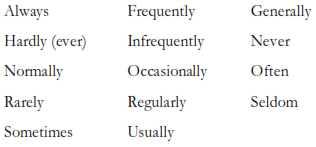

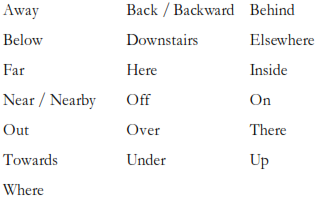

Frequency

These are adverbs that tell or ask how many times, or how often, something is done. These adverbs should be placed directly before the main verb. A short list of adverbs of frequency is provided below:

# NOTE: These adverbs are suited for emphasizing or de-emphasizing certain verbs or phrases.

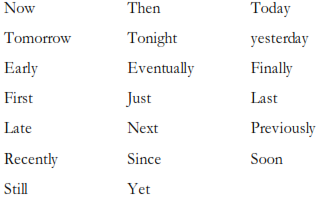

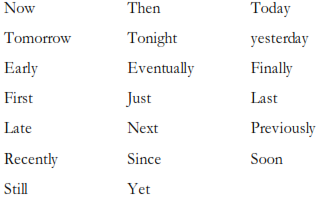

Time

Adverbs of time describe when something was done. They are usually placed at the end of a sentence (i.e. I worked yesterday). Below is a short list:

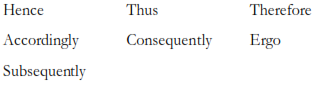

Purpose

Often referred to as adverbs of cause or adverbs of reason, these adverbs describe why something is happening or is done.

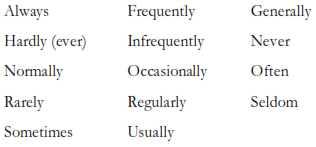

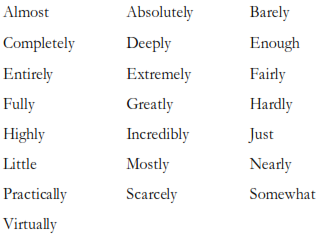

Degree

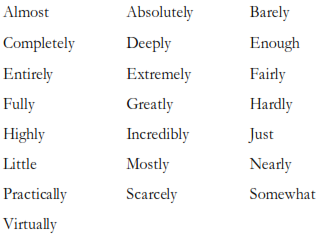

Adverbs of degree describe the extent to which something is done. Adverbs of degree should be placed just before the verb they modify (i.e. “He almost finished everything”). Below is a list of adverbs of degree:

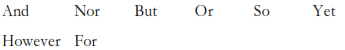

Conjunctions

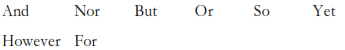

Conjunctions are words that join two sentences or two clauses together. The most common type of conjunctions are called coordinating conjunctions. There are seven coordinating conjunctions:

# NOTE: You can use a conjunction in your sentences, stretching out the vowel sound of the conjunction in order to give you time to think of what to say next. This prevents the listener from thinking that you have finished speaking.

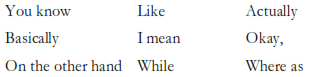

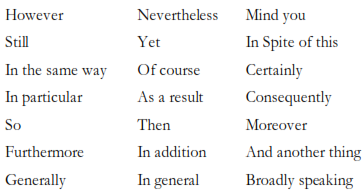

Discourse Markers

Discourse markers work much in the same way that conjunctions do… As a matter of fact, many conjunctions are used as discourse markers. A discourse marker is a word or phrase used at the beginning of a phrase or sentence, and may be used to join two sentences together They are imported from other classes of words, such as conjunctions, adjectives, adverbs, etc.

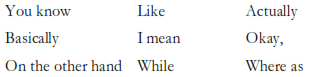

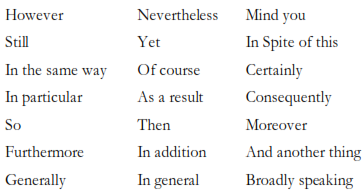

Discourse markers may also be used at the end of a sentence to instigate turn-taking, or to suggest to the speaker to either continue speaking or to elaborate on what has already been said. When we say something, for instance, and end our sentence with “so…” we are telling the other person to continue, or to continue where we left off. The same goes for such words as “and”, “okay…”, or “like…”. Some common discourse markers are provided below:

Example: Okay, so yesterday was the best day of my life. Of course, it didn’t start out that way. Generally, my days never start out very good, until I have that first cup of coffee. Certainly, however, there is always room for deviance, and that’s what happened yesterday.

In the above example, I used five discourse markers in this one paragraph of text… Most people do not use discourse markers so frequently. You will also notice in the use of “Certainly, however” that discourse markers may often be stacked, generally with no more than two discourse markers in sequence.

Strategic Silence

While speech is important, as is the choice of the right words and phrases for every situation, so too, does silence have great qualities. Sometimes, it is best not to say anything at all.

Silence can be eloquent, meaning that is serves a function, and should be considered a relevant part of any communicative act. It plays a part in communicating messages just as speech does. In this sense, it is called eloquent silence. In music and poetry, this eloquent silence is called a “caesura”, and is defined as “a complete pause in a line of poetry and/or in a musical composition”. Below are several ways in which it may do this in speech:

Discourse Marker

Above we spoke about discourse markers, and how they are often used to join two sentences. Silence may also be used in such a manner. We may use silence in our own speaking, so to leave a pause as the joining of two sentences (often combined with some form of body-language); or we may use silence as a means of instigating turn-taking.

Without The Polarity of Silence,

The System of Language Would Fall.

- Susan Sontag

Grammatik Marker

My favorite use of silence is that of a Grammatik marker. When we read a passage from a piece of literature, we find marks of grammar that set one phrase or sentence apart from another… Such marks of grammar also indicate pause or silence:

1) Silence as Parenthesis: Parenthesis is used for information that does not follow the natural flow of your sentence, but that needs to be included anyway. Parenthesis are often used to provide additional information that clarifies or supplements something already said. In writing, parenthesis is signified by the use of brackets, in speech, however, it is signified through the use of a short pause before and after the parenthesis.

2) Silence as Ellipse or Dash: An ellipse, in writing, is a set of three consecutive dots used to signify an extended pauses. A dash has the same effect, but usually to a shorter degree. Dashes, however, generally unlike the ellipse, are often used before and after a phrase so as to set it apart from the rest of the sentence (possibly as emphasis).

3) Silence After Commas or Periods: A period signifies the end of a phrase or sentence, or otherwise the completion of a stream of thought. As it signifies an ending it is only natural that there should be a stop or pause after periods.

4) Silence After Exclamation: The exclamation mark is probably the most powerful marker in grammar. It signifies a rising of expression. An emotional surge. Excitement! With the rise of emotion must come a stop, similar to the pause after a period, except the pause after an emotional statement is generally a bit longer as to give the reader a moment to catch his breathe.

Speech Act

If we remember from chapter 1, a speech act is the act of saying something through speech, other than the literary meaning of the speech. It encompasses the intent of the speaker. Silence, also, can take on form by way of the intent of the speaker… When one person speaks to another, and the second person purposely does not reply, it often means “I’m angry at you”. However, if being asked for approval on a particular subject, it can also mean “I disapprove!” On the brighter side of things, imagine two lovers sitting at a park bench enjoying the sunset together…No words are needed for mutual understanding – It is clear that the silence of both people is effectively saying “I’m happy to be with you right now”.

Silence can provide great insight into the thoughts of others, whether it be excitement, mourning, reverence, or astonishment. In each of these, it must be understood how the context of the situation effects the individual who is silent. Other considerations such as previous statements, body-language and other nonverbal language may also be taken into account.

Indicating Response

Silence can be an indication of response, especially in response to a direct question. For example: A judge in a court of law may ask a question to the respondent… To answer in silence, the respondent would be conceding guilty.

As another example: A husband and wife walk into a lady’s fashion store… The wife says “Do you like this dress?”, and the man doesn’t answer. A response is given.

Requesting Response

Silence often terrifies people. In an interpersonal situation, where no one speaks and there is a sense of dead silence (a complete lack of noise), one person is bound to begin talking sooner or later. When a question is asked, and the listener does not respond, the same sense of dead silence can be felt. In such a case, the speaker often breaks the silence by continuing to speak, either by adding additional information and returning to request an answer, or possibly accepting no response and changing the subject to a different topic. What would happen though, if the speaker simply waited for a reply… The listener would eventually say something!

Withholding Information

Silence can also be a means of withholding information. To plead the fifth, in the United States, means to say nothing. When somebody asks a question, you have the option of answering it in full, provide only a partial answer, or not answering at all. Depending on the context, you may have a strategic advantage in choosing one option over the other. The art of information manipulation, however, is a subject far too great for the likes of this book.

Emotive Language

Emotive language is the use of words that provoke some type of emotional response. If you really want to captivate people and pull their attention in towards you, you must aim to get them emotionally involved in the conversation.

Emotive language makes use of descriptive language as discussed above… With a special emphasis on adjectives that describe emotions (i.e. happy, sad, excited, lonely, etc.).

In the context of emotive language, all words can be thought of as divided into two main categories:

1) Denotation: The denotative meaning of a word is the actual or literary meaning of the word itself. This is fairly synonymous with the explicit meaning of words as discussed in chapter 4.

2) Connotation: The connotative meaning of a words is the essential idea that the word represents, generally in the view of the majority (of the people). This is similar to the implicit meaning of words as described in chapter 4.

Just to ensure understanding of this, let’s look at a quick scenario: If I was to give a yellow rose to a friend, and say “I appreciate you”, the yellow rose would signify good friendship, this is the connotation of a yellow rose as generally understood by the vast majority. If, however, the rose was red, the red rose would signify a stronger interpersonal relationship – Such as that between lovers.

In the use emotive language, we restructure our phrases so that the most emotionally implicit meaning of a word is used, instead of the explicit or denotative meaning. Consider the following:

“A house is just a structure; but a home is where you hang your hat”.

The connotative meaning of words change the way in which the entire sentence is perceived through ideology (using words as ideas rather than the literal significance). It evokes an emotional response… The word "child" has a different meaning to most people, then the word "kid" (child relates to closeness and innocence, while "kid" simply refers to person who is not an adult, and could be of any age between 1 week and twenty years)… To elaborate on this, it is more likely that we would say call our own child “a child”, and someone else’s child “A kid” because the emotional involvement is greater with our own children, and significantly less with someone else’s.

The word “woman” may refer to any female over the age of 20 years; while the word “lady” tends to refer to a woman of royal or similar class. The word “complete” simply refers to all pieces being accounted for; while the word “system” refers to a complete set that works together to provide specified results.

# NOTE: Learn to grow your vocabulary of synonyms, and reconsider the denotative and connotative meaning of words – Understand the impact of the words you use on your listeners. Use sentences that promote the connotative meaning when you want to excite an emotional response.

Figure of Speech

A figure of speech is a word, phrase or sentence that is designed to create an effect of some sort. Many figures of speech have become commonplace in day-to-day conversation, while others appear to be more confined to literature, and others yet are not often used at all. Below, I’ve included only those that are commonly appropriate for spoken conversation.

Anaphora

Anaphora occurs when at the first part of a sentence is repeated in the second part of the same sentence. Sometimes, a word is changed so that it doesn’t sound so much like a repetition. See the example below:

“Everybody likes winners, but nobody likes losers”

Cliché

A cliché is an expression that has been over-used, so that it has lost its expressive power. Examples include:

“Turn over a new leaf”

“A rose by any other name would still smell as sweet”

Hyperbole

This is the use of exaggerations for the purpose of amplifying a given statement. Most people use hyperbole naturally in day to day language. For example, if a task takes 5-6 hours to complete, we may say “It took the whole day” (did it really take the whole day?).

# NOTE: Hyperbole may be used to add humor to a conversation; or it may be used to add a sense of seriousness to the message.

Idiom

An idiom is a common expression that has come to mean something other than it’s literary meaning. Common Idioms include:

“It’s raining cats and dogs”

“That cost me an arm and a leg”

# NOTE: Much like clichés, idioms have become common because of their over-use. Like clichés, idioms should be avoided.

Innuendo

Innuendo involves opinions, remarks or terminology that insinuates or provides subtle or indirect observation about a person or thing, usually of a salacious, critical, or wrongful nature. Examples of innuendo include: He was shooting his mouth off, and killed the conversation; or “He’s not the smartest nail in the bunch”.

# NOTE: Innuendo can be used to add humor to a conversation when speaking about events or inanimate objects. Innuendo should be avoided when referring to people to avoid future complications in relations

Litote

This is a figure of speech in which an understatement is used for rhetorical effect, usually by using double negatives. Example: “He’s not the most intelligent person in the world”. (meaning he’s stupid).

# NOTE: Litotes may be commonly used amongst friends in a non-professional environment; but should be avoided in professional conversation as they devalue the subject of the conversation.

Metaphor

Metaphor is a very common figure of speech in where one word is equated to another or where one word is used to signify another, usually in an idealistic fashion. Metaphors often use comparative words to relate one thing to another. For example: the use of the phrase “broken heart” to suggest that a person is hurt and sad, however, the heart itself is not actually broken.

# NOTE: Because people often use comparisons to understand new ideas, metaphors can be used in explanation or to help reinforce a message (so others can comprehend the message better).

Metonymy

This occurs where one word is called by one of its associated words or ideas instead of calling it by its own name or instead of calling it what it really is.

A famous example of the use of metonymy is the phrase “The pen is mightier than the sword” (“pen” referring the writing skills, and “sword” referring to the use of force)

Another example is to say: “I need a hand with my suitcases” (“hand” refers to help). As another example: “Wall Street” is often used to refer to the U.S. financial sector; and “Hollywood” is used to refer to the U.S. major motion picture industry.

# NOTE: You can create your own metonymy, such that may be only understood between yourself and another person -The consistent use of which can help develop a relational bond. You can also use a commonly understood metonymy that is relevant to the conversation when you believe it would be understood by the listener, even if simply to change up your conversation, .

Oxymoron

An oxymoron occurs when two terms are used together, that would ordinarily contradict each other.

Many oxymoron’s are already a part of everyday speech or are commonly understood. Examples of oxymoron’s include: Clearly confused; act naturally; pretty ugly; alone together.

# NOTE: Because of their nature of including contradictory words, oxymoron’s may be used to add a hint of humor to the conversation. Place a stress or emphasis on the oxymoron when using them. Be careful, however, not to use oxymoron’s in a condescending