CREDIT

Some people think that credit cards are evil and that keeping kids on the other side of the moat is the only way to keep them safe. But that assumes that credit card companies will never breach the castle. Hey, it’s only a matter of time. Far better that kids know what to do with plastic when they finally have some in their hot little hands. And who better to teach them than you?

The first time most kids learn about credit is when they go off to university and the credit card companies start throwing cards at them. With no experience and very little understanding of the long-term negative ramifications, kids start to charge. And they charge, charge, charge until they’re in a hole. That’s because they’ve had no prior experience with how a credit card works, or how to use one so that it’s a tool and not a Debt Pit.

All it takes is a little time and a thoughtful approach to help your children see credit for what it is: useful when used correctly, deadly when it isn’t. When you use your credit card to purchase gas or pay for a new bathing suit, take the time to explain how credit cards work. Show your children that you’re only putting on the card what you can afford to pay off when the bill arrives. Explain that you use your card for good reasons, not just to scratch your consumer itch, because this debt has to be repaid.

Even relatively young kids can get in on this lesson. Issue your 10-year-old a credit card on the Bank of Mom & Dad. (Have her design it herself, if you like.) Draw up a cardholder’s agreement that both of you sign. It should clearly state:

- How much credit she can use: “Charges can be made to this card up to a credit limit of $40.”

- When the statement will arrive: “Statements will arrive on the 15th of each month.”

- The date by which it must be paid—called the “grace period”: “Payments must be made by the 30th of each month.”

- The minimum payment required: “The minimum payment is 25% of the outstanding balance.”

- How much interest will be charged if the balance is not paid off in full: “If the balance is not paid in full and on time, interest will be charged on the entire balance at a rate of 25% a year or 2% a month.”

It’s important that you use a fairly high interest rate in your agreement. If you wuss out and charge just 5% a year, the lesson that using someone else’s money can be expensive is likely to get lost. Charge a whopping amount of interest (hey, department stores charge more than 24%), and the lesson will be made more real for your kids.

Your child can now use her credit card when she goes shopping with you. If she sees something she wants to buy, she gives you her card and you make the purchase on her behalf using your money. You give her a charge receipt.

Remind her that if she doesn’t have the money at home ready to pay the card off in full when the bill comes in, she’ll have to allocate her future allowance (or babysitting money) to pay the bill when it arrives. Make the point clear: she is spending money she hasn’t yet earned, and she’ll pay interest to do so if she can’t come up with the money in time.

If she spends more than she can afford, or makes her payments late, you’ll have to charge her interest on the balance. Use 24% as your interest rate for this exercise, and don’t give in. To calculate the interest, multiply her monthly balance by 2% (which is the equivalent of 24% a year). So if she owes $16.50, the calculation would look like this: $16.50 x 2 ÷ 100 = $0.33.

Point out that she is paying that 33¢ for having used your money for a month. It is like she “rented” the $16.50 for a month, and the cost was 33¢. And if she doesn’t pay it off soon, it will continue to cost her money every month to keep “renting” the money she’s charged on her credit card.

Once your child is 16 or so (you’ll have to gauge his maturity), you may wish to get him an actual credit card (it will have to be in your name since only those 18 and older can have a credit card of their own) and start him using it and repaying it regularly. This is a habit, and one well worth the effort to form. By the time your child is 18, he should have a card in his own name so he can start building a credit history.

As you teach your credit lessons, don’t skip steps because you think they should be obvious to your teenager. Start by explaining how credit cards work.

- Emphasize the connection between charging one month and paying the next: “Since there is a lag between when you use the card and when you must actually pay for the purchases you made, it is easy to forget what you bought. You need to keep track of what you’re buying and what you owe so that you know you’ll have the money to pay the balance when the bill comes in. Here’s a notebook to help you keep track.”

- Stress that credit is not “free money” unless the balance is paid in full before the grace period expires: “If you leave so much as $1 as a balance on the card, you will have to pay interest ON THE ENTIRE BALANCE. Remember, you’re just ‘renting’ someone else’s money, and they want their rental fee.”

- Explain interest and how it compounds if a debt piles up. For this you can go to the Internet. Find a credit card repayment calculator and put in a balance of $1,000. Choose an interest rate of 24% and the minimum monthly payment option. Then let the calculator do its work to show how much interest will build up on the card over time.

- Read the fine print and review key terms such as late fees and over-balance charges: “If you’re late with a payment, the credit card company sees that as an opportunity to make more money, so they make you pay an extra fee. And if you go over your balance, that’s another opportunity for them to make you pay.”

- Talk about how to keep the card safe and what to do if it’s stolen or lost: “If you lend anyone your credit card or share your code, you’re asking to be a victim of identity theft, which is where someone else pretends to be you, shops up a storm, and leaves you responsible for paying it all off. No one else should have access to your card. Keep it somewhere safe, don’t leave your wallet lying around or in a car, and protect your credit identity. If you think you’ve lost your card or that it’s been stolen, report it immediately. You won’t be charged for purchases made if you’ve reported it. If you haven’t, you’re on the hook for whatever has been put on the card.”

- Set limits and monitor your child’s use of the card. He must prove his ability to handle the low limit you’ve established—$100 is good to start— before you increase his responsibility. When he is old enough and ready for a card in his own name, encourage him to shop around for low rates and fees.

- Discuss the importance of a good credit history and how a bad one can get in the way of future borrowing, whether your child needs to buy a car, rent an apartment, or get a mortgage for a house: “A good credit history is like a passport. It lets you get access to other people’s money for things you wish to finance. But a bad credit history is like a wall: you’ll pay a lot of money to get over it, assuming there’s a ladder tall enough. If you ruin your credit history by not being responsible and not paying on time, you’ll limit your options later.”

- Show your child how to get a copy of her credit report, which can be accessed for free once a year at each of Canada’s two credit bureaus, TransUnion and Equifax. Go online and look them up to show your child what can be found on a credit bureau report. The lessons your children learn about plastic at home will stick with them through life. (Well, we can cross our fingers, right?) It’s a better option than the alternative. There are so many people who really don’t know how to use credit appropriately, all because they never developed the discipline of self-regulation through practice.

Not all kids will be suited to using plastic. Not all adults should be using plastic. Be honest about your kids’ organization and sense of discipline. If Molly just doesn’t have the wherewithal to manage credit smartly, tell her that she isn’t well suited to using credit cards and that, until she develops some discipline, she should avoid them like the plague.

Your own values will also come into play when it comes to teaching kids about how to spend money. Whether your family lives on cash or uses plastic, talk with your children about the choices you’ve made and why. And remember that they’re always watching, so be mindful of how your use of plastic influences your children.

Advances and Loans

Whenever I talk about allowances, inevitably questions come up about whether or not I think giving kids loans or advances on their allowances is a good idea. In this case, we’re not talking about a lesson in credit so much as a way of managing kids’ expectations and behaviours. My take on it is that it’s really a matter of personal choice. However, there are some things you should think about when making the decision. Each occasion will warrant consideration on its own merit—there are no hard-and-fast rules—and every experience has the potential to teach a lesson, good or bad.

How often does your kid hit you up for money?

If Boyo is always asking for an advance or loan, he may be having trouble learning how to budget and how to plan for the future. Adults manifest the same lack of skill when, rather than saving for an item, they apply for a loan or use their credit card and carry a balance. The desire for immediate gratification outweighs their patience in implementing a planned spending approach.

However, the cost of this borrow-spend-repay strategy is very high. Every cent in interest paid on a loan (including on a credit card balance) is money wasted. So, do you want your child to become a borrower or to be skilled at planned spending? If Boyo doesn’t ask for a loan or advance with any regularity—if it really is a case of an emergency or a special occasion—then using it as a lesson on how to borrow, and the costs associated, can be worthwhile.

What are your expectations in giving the loan?

If you go to a bank to borrow money, you’re expected to pay the money back. All of it. Not only will the lenders expect you to repay the principal, they’ll also expect you to ante up some interest. And you have to make your payments on time. If you want your child to learn about borrowing, you need to set some expectations.

Are you going to charge interest?

Now don’t come hissing and clawing at me with terms like “usury” and “profit.” I’m not suggesting you build your retirement plan on the back of your child’s borrowing. I am suggesting that if you want children to experience the true impact of using someone else’s money to meet their spending desires, then interest must be a part of the equation. With the lack of cost would go the deterrent to borrow (as small a deterrent as it sometimes appears to be). If you teach them it costs nothing more to acquire that scooter than the ticket price, even when they’re tying up your hard-earned money, are you really preparing them for the credit cards and personal lines of credit that are in their futures? If this is to be a real money lesson, charge them 24%, which translates easily into 2% a month.

What if Sweet Pea won’t repay the loan or allowance advance?

Make the point that inconsistent repayment affects a person’s ability to borrow in the future. If she doesn’t repay the loan, there will be no future borrowing.

You may decide to withhold a part of her allowance and apply that to the repayment of the loan. (In the real world, this is referred to as having your wages “garnished.”) But before you take this step, think of the message you are sending by removing the responsibility for making the repayment from your child. A better lesson would be to insist upon repayment as soon as you have given your child her allowance. Create a chart showing how much she owes. Then each week reduce the amount owed so she can see her progress in repaying the loan.

Let’s say your daughter wanted to buy a new gaming system. She had saved $65 of the $185 she needed. There was a great sale on and she got the item for $145, with a loan of $80 from you. Now that she has the game, you’re having trouble getting her to pay you back. Time to make the chart.

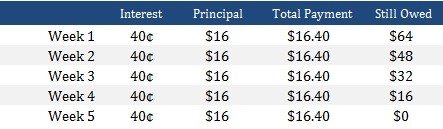

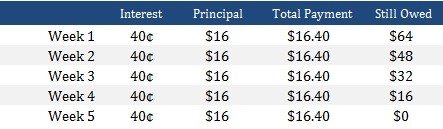

At 24% a year in interest (which works out to 2% a month), your kid’s $80 loan will cost ($80 x 2 ÷ 100) $1.60 a month or 40¢ a week in interest. If you expect that loan to be paid off in five weeks, then she’d also have to give you back ($80 ÷ 5) $16 a week towards the principal (the amount you lent her). So you would draw up a chart that looks like this:

If your child is wishy-washy in keeping her commitments—she repays the loan eventually, but at her own pace and with a fair amount of grumbling—there’s fallout: before you will give her another loan, she must offer you some form of collateral. It may be her bike, her telephone, or her laptop. Make up a loan agreement and include a paragraph that clearly spells out that if the loan is not repaid on time, you have the right to take whatever collateral she has given you until the loan is repaid.

A child who does not repay a loan on time needs to see the consequence of developing a bad credit history: no more loans. And the child who is constantly borrowing may benefit from having a loan request declined, to teach how constant borrowing reduces her ability to repay (and therefore qualify for) yet another loan.

Borrowing itself isn’t a bad thing, provided that we’re borrowing for the right reasons. Knowing when to borrow and how to manage credit are important lessons well worth a few discussions at home where they can be learned in safety.