CHAPTER VIII

A LONDON DRAWING-ROOM

I RECALL the next day, Sunday, with as much interest as any date, for on that day at one-thirty I encountered my first London drawing-room. I recall now as a part of this fortunate adventure that we had been talking of a new development in French art, which Barfleur approved in part and disapproved in part—the Post-Impressionists; and there was mention also of the Cubists—a still more radical departure from conventional forms, in which, if my impressions are correct, the artist passes from any attempt at transcribing the visible scene and becomes wholly geometric, metaphysical and symbolic.

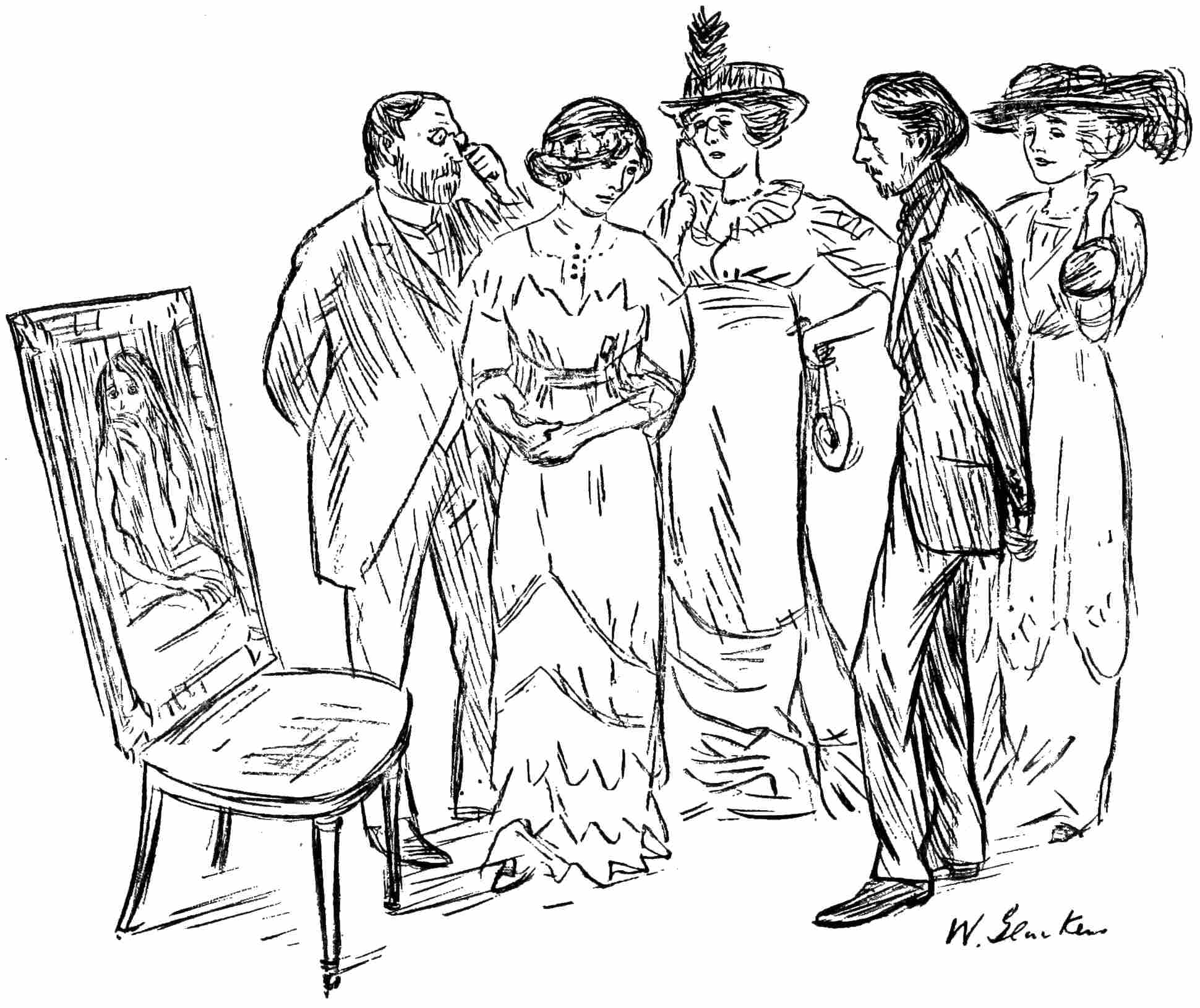

When I reached the house of Mrs. W., which was in one of those lovely squares that constitute such a striking feature of the West End, I was ushered upstairs to the drawing-room, where I found my host, a rather practical, shrewd-looking Dane, and his less obviously Danish wife.

“Oh, Mr. Derrizer,” exclaimed my hostess on sight, as she came forward to greet me, a decidedly engaging woman of something over forty, with bronze hair and ruddy complexion. Her gown of green silk, cut after the latest mode, stamped her in my mind as of a romantic, artistic, eager disposition.

“You must come and tell us at once what you think of the picture we are discussing. It is downstairs. Lady R. is there and Miss H. We are trying to see if we can get a better light on it. Mr. Barfleur has told me of you. You are from America. You must tell us how you like London, after you see the Degas.”

I think I liked this lady thoroughly at a glance and felt at home with her, for I know the type. It is the mobile, artistic type, with not much practical judgment in great matters, but bubbling with enthusiasm, temperament, life.

“Certainly—delighted. I know too little of London to talk of it. I shall be interested in your picture.”

We had reached the main floor by this time.

“Mr. Derrizer, the Lady R.”

A modern suggestion of the fair Jahane, tall, astonishingly lissom, done—as to clothes—after the best manner of the romanticists—such was the Lady R. A more fascinating type—from the point of view of stagecraft—I never saw. And the languor and lofty elevation of her gestures and eyebrows defy description. She could say, “Oh, I am so weary of all this,” with a slight elevation of her eyebrows a hundred times more definitely and forcefully than if it had been shouted in stentorian tones through a megaphone.

She gave me the fingers of an archly poised hand.

“It is a pleasure!”

“And Miss H., Mr. Derrizer.”

“I am very pleased!”

A pink, slim lily of a woman, say twenty-eight or thirty, very fragile-seeming, very Dresden-china-like as to color, a dream of light and Tyrian blue with some white interwoven, very keen as to eye, the perfection of hauteur as to manner, so well-bred that her voice seemed subtly suggestive of it all—that was Miss H.

To say that I was interested in this company is putting it mildly. The three women were so distinct, so individual, so characteristic, each in a different way. The Lady R. was all peace and repose—statuesque, weary, dark. Miss H. was like a ray of sunshine, pure morning light, delicate, gay, mobile. Mrs. W. was of thicker texture, redder blood, more human fire. She had a vigor past the comprehension of either, if not their subtlety of intellect—which latter is often so much better.

Mr. W. stood in the background, a short, stocky gentleman, a little bored by the trivialities of the social world.

“Ah, yes. Daygah! You like Daygah, no doubt,” interpolated Mrs. W., recalling us. “A lovely pigture, don’t you think? Such color! such depth! such sympathy of treatment! Oh!”

Mrs. W.’s hands were up in a pretty artistic gesture of delight.

“Oh, yes,” continued the Lady R., taking up the rapture. “It is saw human—saw perfect in its harmony. The hair—it is divine! And the poor man! he lives alone now, in Paris, quite dreary, not seeing any one. Aw, the tragedy of it! The tragedy of it!” A delicately carved vanity-box she carried, of some odd workmanship—blue and white enamel, with points of coral in it—was lifted in one hand as expressing her great distress. I confess I was not much moved and I looked quickly at Miss H. Her eyes, it seemed to me, held a subtle, apprehending twinkle.

“And you!” It was Mrs. W. addressing me.

“It is impressive, I think. I do not know as much of his work as I might, I am sorry to say.”

“Ah, he is marvelous, wonderful! I am transported by the beauty and the depth of it all!” It was Mrs. W. talking and I could not help rejoicing in the quality of her accent. Nothing is so pleasing to me in a woman of culture and refinement as that additional tang of remoteness which a foreign accent lends. If only all the lovely, cultured women of the world could speak with a foreign accent in their native tongue I would like it better. It lends a touch of piquancy not otherwise obtainable.

Our luncheon party was complete now and we would probably have gone immediately into the dining-room except for another picture—by Piccasso. Let me repeat here that before Barfleur called my attention to Piccasso’s cubical uncertainty in the London Exhibition, I had never heard of him. Here in a dark corner of the room was the nude torso of a consumptive girl, her ribs showing, her cheeks colorless and sunken, her nose a wasted point, her eyes as hungry and sharp and lustrous as those of a bird. Her hair was really no hair—strings. And her thin bony arms and shoulders were pathetic, decidedly morbid in their quality. To add to the morgue-like aspect of the composition, the picture was painted in a pale bluish-green key.

I wish to state here that now, after some little lapse of time, this conception—the thought and execution of it—is growing upon me. I am not sure that this work which has rather haunted me is not much more than a protest—the expression and realization of a great temperament. But at the moment it struck me as dreary, gruesome, decadent, and I said as much when asked for my impression.

“Gloomy! Morbid!” Mrs. W. fired in her quite lovely accent. “What has that to do with art?”

“Luncheon is served, Madam!”

The double doors of the dining-room were flung open.

I found myself sitting between Mrs. W. and Miss H.

“I was so glad to hear you say you didn’t like it,” Miss H. applauded, her eyes sparkling, her lip moving with a delicate little smile. “You know, I abhor those things. They are decadent like the rest of France and England. We are going backward instead of forward—I am quite sure. We have not the force we once had. It is all a race after pleasure and living and an interest in subjects of that kind. I am quite sure it isn’t healthy, normal art. I am sure life is better and brighter than that.”

“I am inclined to think so, at times, myself,” I replied.

We talked further and I learned to my surprise that she suspected England to be decadent as a whole, falling behind in brain, brawn and spirit and that she thought America was much better.

“Do you know,” she observed, “I really think it would be a very good thing for us if we were conquered by Germany.”

I had found here, I fancied, some one who was really thinking for herself and a very charming young lady in the bargain. She was quick, apprehensive, all for a heartier point of view. I am not sure now that she was not merely being nice to me, and that anyhow she is not all wrong, and that the heartier point of view is the courage which can front life unashamed; which sees the divinity of fact and of beauty in the utmost seeming tragedy. Piccasso’s grim presentation of decay and degradation is beginning to teach me something—the marvelous perfection of the spirit which is concerned with neither perfection, nor decay, but life. It haunts me.

The charming luncheon was quickly over and I think I gathered a very clear impression of the status of my host and hostess from their surroundings. Mr. W. was evidently liberal in his understanding of what constitutes a satisfactory home. It was not exceptional in that it differed greatly from the prevailing standard of luxury. But assuredly it was all in sharp contrast to Piccasso’s grim representation of life and Degas’s revolutionary opposition to conventional standards.

“I like it,” he pronounced. “The note is somber, but it is excellent work”

Another man now made his appearance—an artist. I shall not forget him soon, for you do not often meet people who have the courage to appear at Sunday afternoons in a shabby workaday business suit, unpolished shoes, a green neckerchief in lieu of collar and tie, and cuffless sleeves. I admired the quality, the workmanship of the silver-set scarab which held his green linen neckerchief together, but I was a little puzzled as to whether he was very poor and his presence insisted upon, or comfortably progressive and indifferent to conventional dress. His face and body were quite thin; his hands delicate. He had an apprehensive eye that rarely met one’s direct gaze.

“Do you think art really needs that?” Miss H. asked me. She was alluding to the green linen handkerchief.

“I admire the courage. It is at least individual.”

“It is after George Bernard Shaw. It has been done before,” replied Miss H.

“Then it requires almost more courage,” I replied.

Here Mrs. W. moved the sad excerpt from the morgue to the center of the room that he of the green neckerchief might gaze at it.

“I like it,” he pronounced. “The note is somber, but it is excellent work.”

Then he took his departure with interesting abruptness. Soon the Lady R. was extending her hand in an almost pathetic farewell. Her voice was lofty, sad, sustained. I wish I could describe it. There was just a suggestion of Lady Macbeth in the sleep-walking scene. As she made her slow, graceful exit I wanted to applaud loudly.

Mrs. W. turned to me as the nearest source of interest and I realized with horror that she was going to fling her Piccasso at my head again and with as much haste as was decent I, too, took my leave.