CHAPTER XI

THE THAMES

AS pleasing hours as any that I spent in London were connected with the Thames—a murky little stream above London Bridge, compared with such vast bodies as the Hudson and the Mississippi, but utterly delightful. I saw it on several occasions,—once in a driving rain off London Bridge, where twenty thousand vehicles were passing in the hour, it was said; once afterward at night when the boats below were faint, wind-driven lights and the crowd on the bridge black shadows. I followed it in the rain from Blackfriars Bridge, to the giant plant of the General Electric Company at Chelsea one afternoon, and thought of Sir Thomas More, and Henry VIII, who married Anne Boleyn at the Old Church near Battersea Bridge, and wondered what they would think of this modern powerhouse. What a change from Henry VIII and Sir Thomas More to vast, whirling electric dynamos and a London subway system!

Another afternoon, bleak and rainy, I reconnoitered the section lying between Blackfriars Bridge and Tower Bridge and found it very interesting from a human, to say nothing of a river, point of view; I question whether in some ways it is not the most interesting region in London, though it gives only occasional glimpses of the river. London is curious. It is very modern in spots. It is too much like New York and Chicago and Philadelphia and Boston; but here between Blackfriars Bridge and the Tower, along Upper and Lower Thames Street, I found something that delighted me. It smacked of Dickens, of Charles II, of Old England, and of a great many forgotten, far-off things which I felt, but could not readily call to mind. It was delicious, this narrow, winding street, with high walls,—high because the street was so narrow,—and alive with people bobbing along under umbrellas or walking stodgily in the rain. Lights were burning in all the stores and warehouses, dark recesses running back to the restless tide of the Thames, and they were full of an industrious commercial life.

It was interesting to me to think that I was in the center of so much that was old, but for the exact details I confess I cared little. Here the Thames was especially delightful. It presented such odd vistas. I watched the tumbling tide of water, whipped by gusty wind where moderate-sized tugs and tows were going by in the mist and rain. It was delicious, artistic, far more significant than quiescence and sunlight could have made it. I took note of the houses, the doorways, the quaint, winding passages, but for the color and charm they did not compare with the nebulous, indescribable mass of working boys and girls and men and women which moved before my gaze. The mouths of many of them were weak, their noses snub, their eyes squint, their chins undershot, their ears stub, their chests flat. Most of them had a waxy, meaty look, but for interest they were incomparable. American working crowds may be much more chipper, but not more interesting. I could not weary of looking at them.

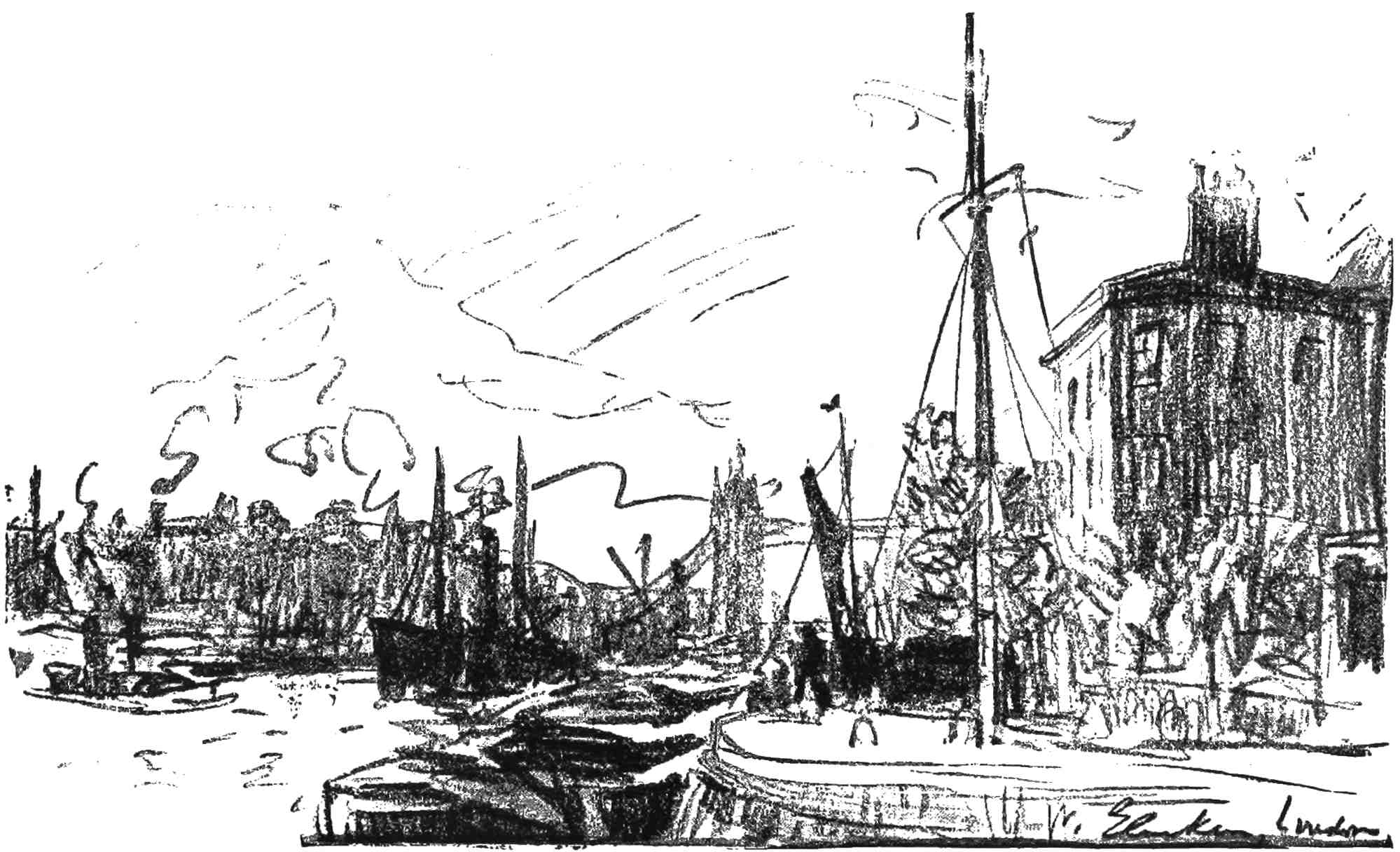

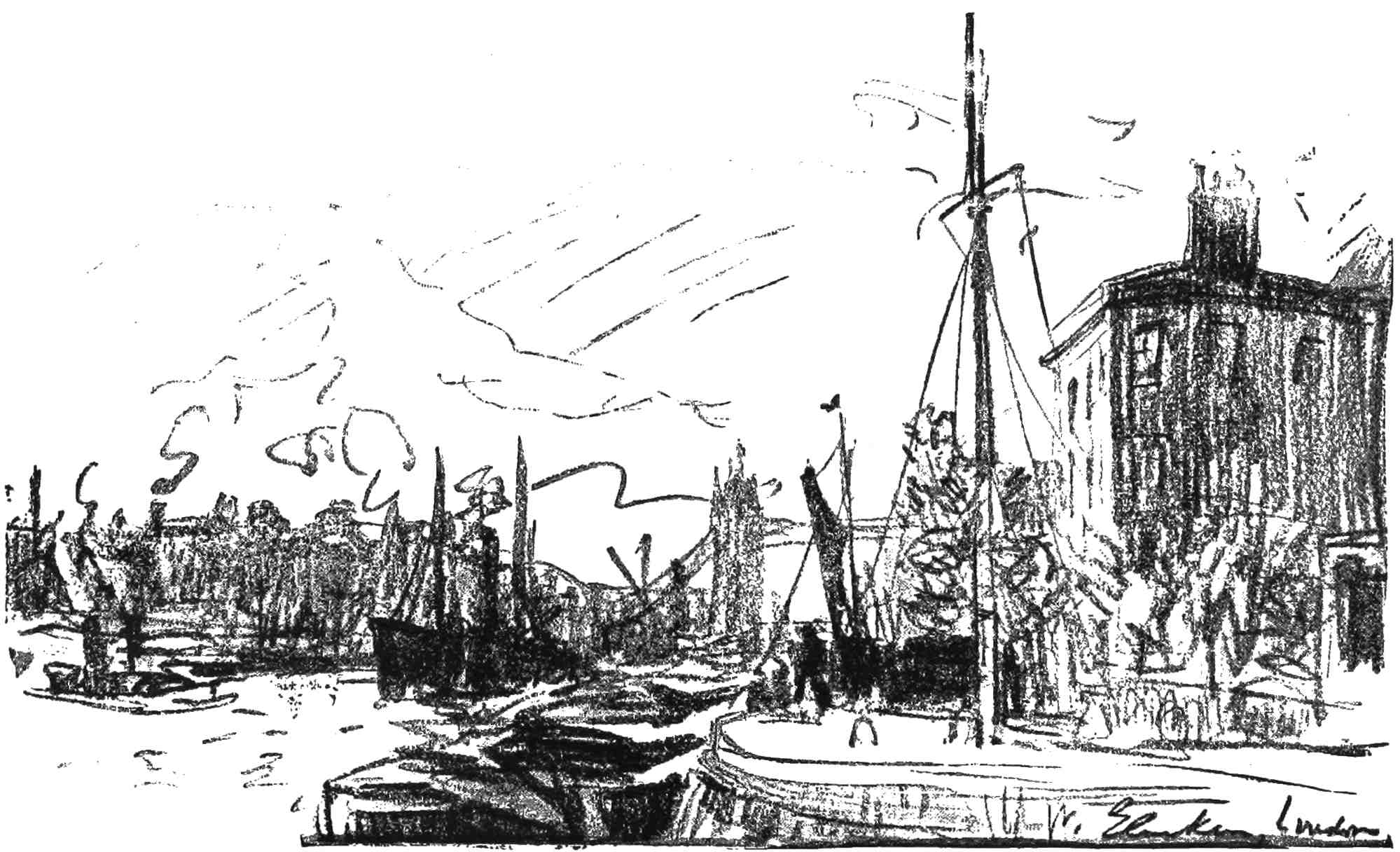

Here the Thames was especially delightful

Lastly I followed the river once more all the way from Cleopatra’s Needle to Chelsea one heavily downpouring afternoon and found its mood varying splendidly though never once was it anything more than black-gray, changing at times from a pale or almost sunlit yellow to a solid leaden-black hue. It looked at times as though something remarkable were about to happen, so weirdly greenish-yellow was the sky above the water; and the tall chimneys of Lambeth over the way, appearing and disappearing in the mist, were irresistible. There is a certain kind of barge which plies up and down the Thames with a collapsible mast and sail which looks for all the world like something off the Nile. These boats harmonize with the smoke and the gray, lowery skies. I was never weary of looking at them in the changing light and mist and rain. Gulls skimmed over the water here very freely all the way from Blackfriars to Battersea, and along the Embankment they sat in scores, solemnly cogitating the state of the weather, perhaps. I was delighted with the picture they made in places, greedy, wide-winged, artistic things.

Finally I had a novel experience with these same gulls one Sunday afternoon. I had been out all morning reconnoitering strange sections of London, and arrived near Blackfriars Bridge about one o’clock. I was attracted by what seemed to me at first glance thousands of gulls, lovely clouds of them, swirling about the heads of several different men at various points along the wall. It was too beautiful to miss. It reminded me of the gulls about the steamer at Fishguard. I drew near. The first man I saw was feeding them minnows out of a small box he had purchased for a penny, throwing the tiny fish aloft in the air and letting the gulls dive for them. They ate from his hand, circled above and about his head, walked on the wall before him, their jade bills and salmon-pink feet showing delightfully.

I was delighted, and hurried to the second. It was the same. I found the vender of small minnows near by, a man who sold them for this purpose, and purchased a few boxes. Instantly I became the center of another swirling cloud, wheeling and squeaking in hungry anticipation. It was a great sight. Finally I threw out the last minnows, tossing them all high in the air, and seeing not one escape, while I meditated on the speed of these birds, which, while scarcely moving a wing, rise and fall with incredible swiftness. It is a matter of gliding up and down with them. I left, my head full of birds, the Thames forever fixed in mind.

I went one morning in search of the Tower, and coming into the neighborhood of Eastcheap witnessed that peculiar scene which concerns fish. Fish dealers, or at least their hirelings, always look as though they had never known a bath and are covered with slime and scales, and here, they wore a peculiar kind of rubber hat on which tubs or pans of fish could be carried. The hats were quite flat and round and reminded me of a smashed “stovepipe” as the silk hat has been derisively called. The peasant habit of carrying bundles on the head was here demonstrated to be a common characteristic of London.

On another morning I visited Pimlico and the neighborhood of Vincent Square. I was delighted with the jumble of life I found there, particularly in Strutton Ground and Churton Street. Horse Ferry Road touched me as a name and Lupus Street was strangely suggestive of a hospital, not a wolf.

It was here that I encountered my first coster cart, drawn by the tiniest little donkey you ever saw, his ears standing up most nobly and his eyes suggesting the mellow philosophy of indifference. The load he hauled, spread out on a large table-like rack and arranged neatly in baskets, consisted of vegetables—potatoes, tomatoes, cabbage, lettuce and the like. A bawling merchant or peddler followed in the wake of the cart, calling out his wares. He was not arrayed in coster uniform, however, as it has been pictured in America. I was delighted to listen to the cockney accent in Strutton Ground where “’Ere you are, Lydy,” could be constantly heard, and “Foine potytoes these ’ere, Madam, hextra noice.”

In Earl Street I found an old cab-yard, now turned into a garage, where the remnants of a church tower were visible, tucked away among the jumble of other things. I did my best to discover of what it had been a part. No one knew. The ex-cabman, now dolefully washing the wheels of an automobile, informed me that he had “only been workin’ ’ere a little wile,” and the foreman could not remember. But it suggested a very ancient English world—as early as the Normans. Just beyond this again I found the saddest little chapel—part of an abandoned machine-shop, with a small hand-bell over the door which was rung by means of a piece of common binding-twine! Who could possibly hear it, I reflected. Inside was a wee chapel, filled with benches constructed of store boxes and provided with an altar where some form of services was conducted. There was no one to guard the shabby belongings of the place and I sat down and meditated at length on the curiosity of the religious ideal.

In another section of the city where I walked—Hammersmith—and still another—Seven Kings—I found conditions which I thought approximated those in the Bronx, New York, in Brooklyn, in Chicago and elsewhere. I could not see any difference between the lines of store-front apartment houses in Seven Kings and Hammersmith and Shepherd’s Bush for that matter, and those in Flatbush, Brooklyn or the South End of Philadelphia. You saw the difference when you looked at the people and, if you entered a tavern, America was gone on the instant. The barmaid settled that and the peculiar type of idler found here. I recall in Seven Kings being entertained by the appearance of the working-men assembled, their trousers strapped about the knees, their hats or caps pulled jauntily awry. Always the English accent was strong and, at times, here in London, it became unintelligible to me. They have a lingo of their own. In the main I could make it out, allowing for the appearance or disappearance of “h’s” at the most unexpected moments.

The street cars in the outlying sections are quite the same as in America and the variety of stores about as large and bright. In the older portions, however, the twisting streets, the presence of the omnibus in great numbers, and of the taxi-stands at the more frequented corners, the peculiar uniforms of policemen, mail-men, street-sweepers (dressed like Tyrolese mountaineers), messenger-boys, and the varied accoutrements of the soldiery gave the great city an individuality which caused me to realize clearly that I was far from home—a stranger in a strange land. As charming as any of the spectacles I witnessed were the Scotch soldiers in bare legs, kilts, plaid and the like swinging along with a heavy stride like Norman horses or—singly—making love to a cockney English girl on a ’bus top perhaps. The English craze for pantomime was another thing that engaged my curious attention and why any reference to a mystic and presumably humorous character known as “Dirty Dick” should evoke such volumes of applause.