CHAPTER XXXVIII

A NIGHT RAMBLE IN FLORENCE

WHATEVER the medieval atmosphere of Florence may have been, and when I was there the exterior appearance of the central heart was obviously somewhat akin to its fourteenth- and fifteenth-century predecessor, to-day its prevailing spirit is thoroughly modern. If you walk in the Piazza della Signoria or the Piazza del Duomo or the Via dei Calzaioli, the principal thoroughfare, you will encounter most of the ancient landmarks—a goodly number of them, but they will look out of place, as in the case of the palaces with their windowless ground floors, built so for purposes of defense, their corner lanterns, barricaded windows, and single great entrances easily guarded. To-day these regions have, if not the open spacing of the modern city, at least the commercial sprightliness and matter-of-fact business display and energy which is characteristic of commerce everywhere.

I came to the Piazza della Signoria, the most famous square of the city, quite by accident, the first night following a dark, heavily corniced street from my hotel and at once recognized the Palazzo Vecchio, with its thin angular tower; the Loggia dei Lanzi, where in older times public performances were given in the open; and the equestrian statue of Cosimo I. I idled long here, examining the bronze slab which marks the site of the stake at which Savonarola and two other Dominicans were burned in 1498, the fountain designed by Bartolommeo Ammanati; the two lions at the step of the Loggia and Benvenuto Cellini’s statue of “Perseus” with the head of Medusa. A strange genius, that. This figure is as brilliant and thrilling as it is ghastly.

It was a lovely night. The moon came up after a time as it had at Perugia and Assisi and I wandered about these old streets, feeling the rough brown walls, looking in at the open shop windows, most of them dark and lighted by street lamps, and studying always the wide, overhanging cornices. All really interesting cities are so delightfully different. London was so low, gray, foggy, heavy, drab, and commonplace; Paris was so smart, swift, wide-spaced, rococo, ultra-artistic, and fashionable; Monte Carlo was so semi-Parisian and semi-Algerian or Moorish, with sunlight and palms; Rome was so higgledy-piggledy, of various periods, with a strange mingling of modernity and antiquity, and over all blazing sunlight and throughout all cypresses; and now in Florence I found the compact, dark atmosphere, suggestive of what Paris once was, centuries before, with this distinctive feature, that the wide cornice is here an essential characteristic. It is so wide! It protrudes outward from the building line at least three or four feet and it may be much more, six or seven. One thing is certain, as I found to my utter delight on a rainy afternoon, you can take shelter under its wide reach and keep comparatively dry. Great art has been developed in making it truly ornamental and it gives the long narrow streets a most individual and, in my judgment, distinguished appearance.

It was quite by accident, also, on this same evening that I came upon the Piazza del Duomo where the street cars are. I did not know where I was going until suddenly turning a corner there I saw it—the Campanile at last and a portion of the Cathedral standing out soft and fair in the moonlight! I shall always be glad that I saw it so, for the strange stripe and arabesque of its stone work,—slabs of white or cream-colored stone interwoven in lovely designs with slabs of slate-colored granite, had an almost eerie effect. It might have been something borrowed from Morocco or Arabia or the Far East. The dome, too, as I drew nearer, and the Baptistery soared upwards in a magnificent way and, although afterwards I was sorry that the municipality has never had sense enough to tear out the ruck of buildings surrounding it and leave these three monuments—the Cathedral, the Campanile, and the Baptistery—standing free and clear, as at Pisa, on a great stone platform or square,—nevertheless, cramped as I think they are, they are surely beautiful.

I was not so much impressed by the interior of the cathedral. Its beauty is largely on the outside.

I ascended the Campanile still another day and from its height viewed all Florence, the windings of the Arno, San Miniato, Fiesole, but, try as I might, I could not think of it in modern terms. It was too reminiscent of the Italy of the Medici, of the Borgias, Julius II, Michelangelo and all the glittering company who were their contemporaries. One thing that was strongly impressed upon me there was that every city should have a great cathedral. Not so much as a symbol or theory of religion as an object of art, something which would indicate the perfection of the religious ideal taken from an artistic point of view. Here you can stand and admire the exquisite double windows with twisted columns, the infinite variety of the inlaid marble work, and the quaint architecture of the niches supported by columns. It was after midnight and the moon was high in the heavens shining down with a rich springlike effect before I finally returned from the Duomo Square, following the banks of the Arno and admiring the shadows cast by the cornices and so finally reached my hotel and my bed.

The Uffizi and Pitti collections of paintings are absolutely the most amazing I saw abroad. There are other wonderful collections, the Louvre being absolutely unbelievable for size; but here the art is so uniformly relative to Italy, so identified with the Renaissance, so suggestive of the influence and the patronage which gave it birth. The influence of religion, the wealth of the Catholic Church, the power of individual families such as the Medici and the Dukes of Venice are all clearly indicated. Botticelli’s “Adoration of the Magi” in the Uffizi, showing the proud Medici children, the head of Cosimo Pater Patriae, and the company of men of letters and statesmen of the time, all worked in as figures about the Christ child, tell the whole story. Art was flattering to the nobility of the day. It was dependent for its place and position upon religion, upon the patronage of the Church, and so you have endless “Annunciations,” “Adorations,” “Flights into Egypt,” “Crucifixions,” “Descents from the Cross,” “Entombments,” “Resurrections,” and the like. The sensuous “Magdalena,” painted for her form and the beauty of suggestion, you will encounter over and over again. All the saints in the calendar, the proud Popes and Cardinals of a dozen families, the several members of the Medici family—they are all there. Now and then you will encounter a Rubens, a Van Dyck, a Rembrandt, or a Frans Hals from the Netherlands, but they are rare. Florence, Rome, Venice, Pisa, and Milan, are best represented by their own sculptors, painters and architects and it is the local men largely in whom you rejoice. The bits from other lands are few and far between.

Rome for sculptures, frescoes, jewel-box churches, ancient ruins, but Florence for paintings and the best collections of medieval artistic craftsmanship.

In the Uffizi, the Pitti, and the Belle Arti I browsed among the vast collections of paintings sharpening my understanding of the growth of Italian art. I never knew until I reached Florence how easy it is to trace the rise of Christian art, to see how one painter influenced another, how one school borrowed from another. It is all very plain. If by the least effort you fix the representatives of the different Italian schools in mind, you can judge for yourself.

I returned three times to look at Botticelli’s “Spring” in the Belle Arti, that marvelous picture which I think in many respects is the loveliest picture in the world, so delicate, so poetically composed, so utterly suggestive of the art and refinement of the painter and of life at its best. The “Three Graces,” so lightly clad in transparent raiment, are so much the soul of joy and freshness, the utter significance of spring. The ruder figures to the left do so portray the cold and blue of March, the warmer April, and the flower-clad May! I could never tire of the artistry which could have March blowing on April’s mouth from which flowers fall into the lap of May. Nor could I weary of the spirit that could select green, sprouting things for the hem of April’s garment; or above Spring’s head place a wingèd and blindfolded baby shooting a fiery arrow at the Three Graces. To me Botticelli is the nearest return to the Greek spirit of beauty, grace and lightness of soul, combined with later delicacy and romance that the modern world has known. It is so beautiful that for me it is sad—full of the sadness that only perfect beauty can inspire.

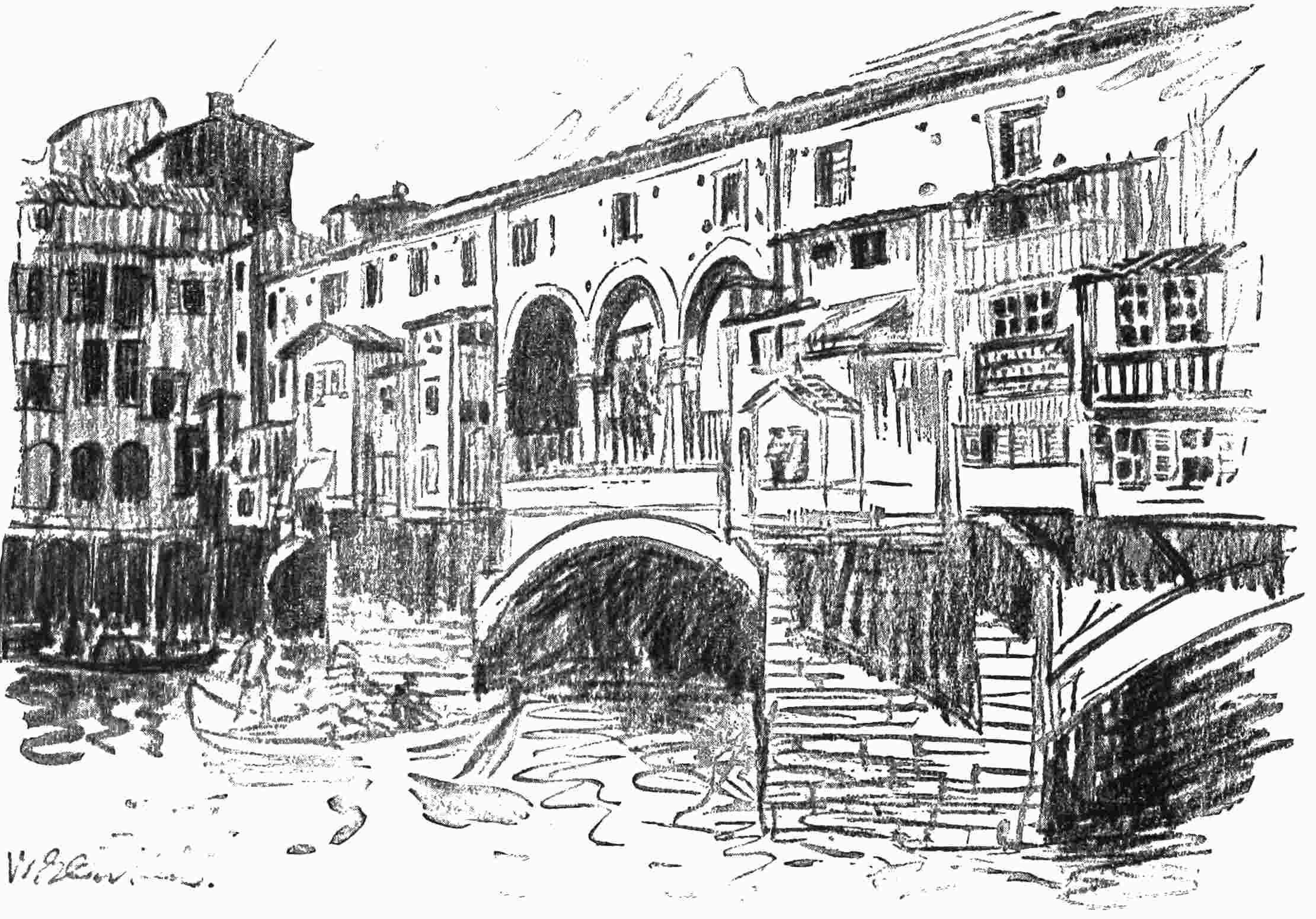

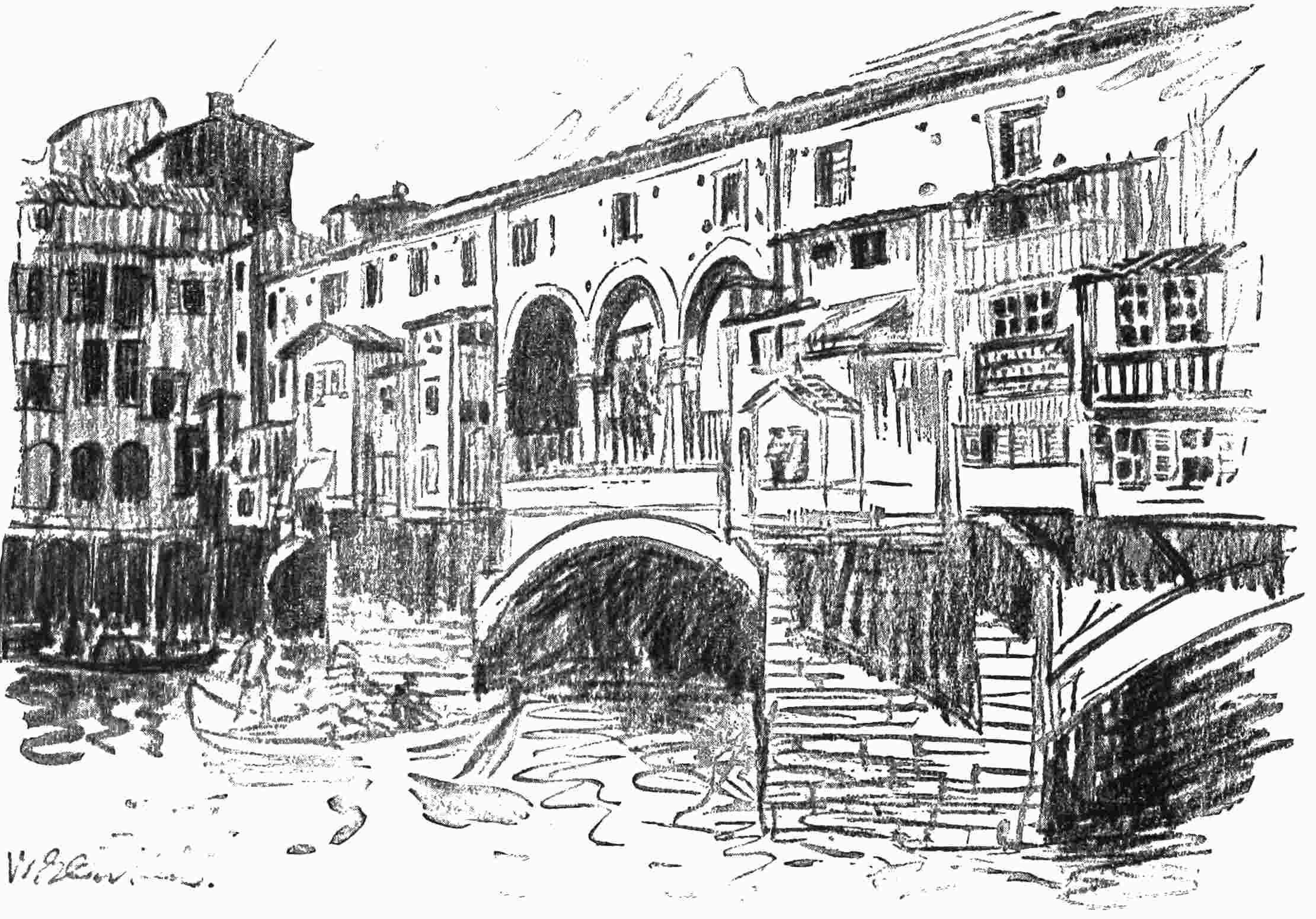

I sated myself on the house fronts or backs below the Ponte Vecchio

I think now, of all the places I saw in Italy, perhaps Florence really preserves in spite of its changes most of the atmosphere of the past, but that is surely not for long, either; for it is growing and the Germans are arriving. They were in complete charge of my hotel here and of other places, as I shortly saw, and I fancy that the future of northern Italy is to be in the hands of the Germans.

As I walked about this city, lingering in its doorways, brooding over its pictures, reconstructing for myself the life of the Middle Ages, I could not help thinking how soon it must all go. No doubt the churches, palaces, and museums will be retained in their present form for hundreds of years, and they should be, but soon will come wider streets and newer houses even in the older section (the heart of the city) and then farewell to the medieval atmosphere. In all likelihood the wide cornices, now such a noticeable feature of the city, will be abandoned and then there will be scarcely anything to indicate the Florence of the past. Already the street cars were clang-clanging their way through certain sections.

The Arno here is so different from the Tiber at Rome; and yet so much like it, for it has in the main the same unprepossessing look, running as it does through the city between solid walls of stone but lacking the spectacles of the castle of St. Angelo, Saint Peter’s, the hills and the gardens of the Aventine and the Janiculum. There are no ancient ruins on the Arno,—only the suggestive architecture of the Middle Ages, the wonderful Ponte Vecchio and the houses adjacent to it.

Indeed the river here is nothing more than a dammed stream—shallow before it reaches the city, shallow after it leaves it, but held in check here by great stone dams which give it a peculiarly still mass and depth. The spirit of the people was not the same as that of those in Rome or other cities; the spirit of the crowd was different. A darker, richer, more phlegmatic populace, I thought. The people were slow, leisurely, short and comfortable. I sated myself on the house fronts or backs below the Ponte Vecchio and on the little jewelry shops of which there seemed to be an endless variety; and then feeling that I had had a taste of the city, I returned to larger things. The Duomo, the palaces of the Medici, the Pitti Palace, and that world which concerned the Council of Florence, and the dignified goings to and fro of old Cosimo Pater and his descendants were the things that I wished to see and realize for myself if I could.

I think we make a mistake when we assume that the manners, customs, details, conversation, interests and excitements of people anywhere were ever very much different from what they are now. In three or four hundred years from now people in quite similar situations to our own will be wondering how we took our daily lives; quite the same as our ancestors, I should say, and no differently from our descendants. Life works about the same in all times. Only exterior aspects change. In the particular period in which Florence, and all Italy for that matter, was so remarkable, Italy was alive with ambitious men—strong, remarkable, capable characters. They made the wonder of the life, it was not the architecture that did it and not the routine movements of the people. Florence has much the same architecture to-day, better in fact; but not the men. Great men make great times—and only struggling, ambitious, vainglorious men make the existence of the artist possible, however much he may despise them. They are the only ones who in their vainglory and power can readily call upon him to do great things and supply the means. Witness Raphael and Michelangelo in Italy, Rubens in Holland, and Velasquez in Spain.