CHAPTER XL

MARIA BASTIDA

IN studying out my itinerary at Florence I came upon the homely advice in Baedeker that in Venice “care should be taken in embarking and disembarking, especially when the tide is low, exposing the slimy lower steps.” That, as much as anything I had ever read, visualized this wonder city to me. These Italian cities, not being large, end so quickly that before you can say Jack Robinson you are out of them and away, far into the country. It was early evening as we pulled out of Florence; and for a while the country was much the same as it had been in the south—hill-towns, medieval bridges and strongholds, the prevailing solid browns, pinks, grays and blues of the architecture, the white oxen, pigs and shabby carts, but gradually, as we neared Bologna, things seemed to take on a very modern air of factories, wide streets, thoroughly modern suburbs and the like. It grew dark shortly after that and the country was only favored by the rich radiance of the moon which made it more picturesque and romantic, but less definite and distinguishable.

In the compartment with me were two women, one a comfortable-looking matron traveling from Florence to Bologna, the other a young girl of twenty or twenty-one, of the large languorous type, and decidedly good looking. She was very plainly dressed and evidently belonged to the middle class.

The married Italian lady was small and good-looking and bourgeoise. Considerably before dinner-time, and as we were nearing Bologna, she opened a small basket which she carried and took from it a sandwich, an apple, and a bit of cheese, which she ate placidly. For some reason she occasionally smiled at me good-naturedly, but not speaking Italian, I was without the means of making a single observation. At Bologna I assisted her with her parcels and received a smiling backward glance and then I settled myself in my seat wondering what the remainder of the evening would bring forth. I was not so very long in discovering.

Once the married lady of Bologna had disappeared, my young companion took on new life. She rose, smoothed down her dress and reclined comfortably in her seat, her cheek laid close against the velvet-covered arm, and looked at me occasionally out of half-closed eyes. She finally tried to make herself more comfortable by lying down and I offered her my fur overcoat as a pillow. She accepted it with a half-smile.

About this time the dining-car steward came through to take a memorandum of those who wished to reserve places for dinner. He looked at the young lady but she shook her head negatively. I made a sudden decision. “Reserve two places,” I said. The servitor bowed politely and went away. I scarcely knew why I had said this, for I was under the impression my young lady companion spoke only Italian, but I was trusting much to my intuition at the moment.

A little later, when it was drawing near the meal time, I said, “Do you speak English?”

“Non,” she replied, shaking her head.

“Sprechen Sie Deutsch?”

“Ein wenig,” she replied, with an easy, babyish, half-German, half-Italian smile.

“Sie sind doch Italianisch,” I suggested.

“Oh, oui!” she replied, and put her head down comfortably on my coat.

“Reisen Sie nach Venedig?” I inquired.

“Oui,” she nodded. She half smiled again.

I had a real thrill of satisfaction out of all this, for although I speak abominable German, just sufficient to make myself understood by a really clever person, yet I knew, by the exercise of a little tact I should have a companion to dinner.

“You will take dinner with me, won’t you?” I stammered in my best German. “I do not understand German very well, but perhaps we can make ourselves understood. I have two places.”

She hesitated, and said—“Ich bin nicht hungerich.”

“But for company’s sake,” I replied.

“Mais, oui,” she replied indifferently.

I then asked her whether she was going to any particular hotel in Venice—I was bound for the Royal Danieli—and she replied that her home was in Venice.

Maria Bastida was a most interesting type. She was a Diana for size, pallid, with a full rounded body. Her hair was almost flaxen and her hands large but not unshapely. She seemed to be strangely world-weary and yet strangely passionate—the kind of mind and body that does and does not, care; a kind of dull, smoldering fire burning within her and yet she seemed indifferent into the bargain. She asked me an occasional question about New York as we dined, and though wine was proffered she drank little and, true to her statement that she was not hungry, ate little. She confided to me in soft, difficult German that she was trying not to get too stout, that her mother was German and her father Italian and that she had been visiting an uncle in Florence who was in the grocery business. I wondered how she came to be traveling first class.

The time passed. Dinner was over and in several hours more we would be in Venice. We returned to our compartment and because the moon was shining magnificently we stood in the corridor and watched its radiance on clustered cypresses, villa-crowned hills, great stretches of flat prairie or marsh land, all barren of trees, and occasionally on little towns all white and brown, glistening in the clear light.

“It will be a fine night to see Venice for the first time,” I suggested.

“Oh, oui! Herrlich! Prachtvoll!” she replied in her queer mixture of French and German.

I liked her command of sounding German words.

She told me the names of stations at which we stopped, and finally she exclaimed quite gaily, “Now we are here! The Lagoon!”

I looked out and we were speeding over a wide body of water. It was beautifully silvery and in the distance I could see the faint outlines of a city. Very shortly we were in a car yard, as at Rome and Florence, and then under a large train shed, and then, conveyed by an enthusiastic Italian porter, we came out on the wide stone platform that faces the Grand Canal. Before me were the white walls of marble buildings and intervening in long, waving lines a great street of water; the gondolas, black, shapely, a great company of them, nudging each other on its rippling bosom, green-stained stone steps, sharply illuminated by electric lights leading down to them, a great crowd of gesticulating porters and passengers. I startled Maria by grabbing her by the arm, exclaiming in German, “Wonderful! Wonderful!”

“Est ist herrlich” (It is splendid), she replied.

We stepped into a gondola, our bags being loaded in afterwards. It was a singularly romantic situation, when you come to think of it: entering Venice by moonlight and gliding off in a gondola in company with an unknown and charming Italian girl who smiled and sighed by turns and fairly glowed with delight and pride at my evident enslavement to the beauty of it all.

She was directing the gondolier where to leave her when I exclaimed, “Don’t leave me—please! Let’s do Venice together!”

She was not offended. She shook her head, a bit regretfully I like to think, and smiled most charmingly. “Venice has gone to your head. To-morrow you’ll forget me!”

And there my adventure ended!

It is a year, as I write, since I last saw the flaxen-haired Maria, and I find she remains quite as firmly fixed in my memory as Venice itself, which is perhaps as it should be.

* * * * *

But the five or six days I spent in Venice—how they linger. How shall one ever paint water and light and air in words. I had wild thoughts as I went about of a splendid panegyric on Venice—a poem, no less—but finally gave it up, contenting myself with humble notes made on the spot which at some time I hoped to weave into something better. Here they are—a portion of them—the task unfinished.

What a city! To think that man driven by the hand of circumstance—the dread of destruction—should have sought out these mucky sea islands and eventually reared as splendid a thing as this. “The Veneti driven by the Lombards,” reads my Baedeker, “sought the marshy islands of the sea.” Even so. Then came hard toil, fishing, trading, the wonders of the wealth of the East. Then came the Doges, the cathedral, these splendid semi-Byzantine palaces. Then came the painters, religion, romance, history. To-day here it stands, a splendid shell, reminiscent of its former glory. Oh, Venice! Venice!

* * * * *

The Grand Canal under a glittering moon. The clocks striking twelve. A horde of black gondolas. Lovely cries. The rest is silence. Moon picking out the ripples in silver and black. Think of these old stone steps, white marble stained green, laved by the waters of the sea these hundreds of years. A long, narrow street of water. A silent boat passing. And this is a city of a hundred and sixty thousand!

* * * * *

Wonderful painted arch doorways and windows. Trefoil and quadrifoil decorations. An old iron gate with some statues behind it. A balcony with flowers. The Bridge of Sighs! Nothing could be so perfect as a city of water.

* * * * *

The Lagoon at midnight under a full moon. Now I think I know what Venice is at its best. Distant lights, distant voices. Some one singing. There are pianos in this sea-isle city, playing at midnight. Just now a man silhouetted blackly, under a dark arch. Our gondola takes us into the very hallway of the Royal-Danieli.

* * * * *

Water! Water! The music of all earthly elements. The lap of water! The sigh of water! The flow of water! In Venice you have it everywhere. It sings at the base of your doorstep; it purrs softly under your window; it suggests the eternal rhythm and the eternal flow at every angle. Time is running away; life is running away, and here in Venice, at every angle (under your window) is its symbol. I know of no city which at once suggests the lapse of time hourly, momentarily, and yet soothes the heart because of it. For all its movement or because of it, it is gay, light-hearted, without being enthusiastic. The peace that passes all understanding is here, soft, rhythmic, artistic. Venice is as gay as a song, as lovely as a jewel (an opal or an emerald), as rich as marble and as great as verse. There can only be one Venice in all the world!

* * * * *

No horses, no wagons, no clanging of cars. Just the patter of human feet. You listen here and the very language is musical. The voices are soft. Why should they be loud? They have nothing to contend with. I am wild about this place. There is a sweetness in the hush of things which woos, and yet it is not the hush of silence. All is life here, all movement—a sweet, musical gaiety. I wonder if murder and robbery can flourish in any of these sweet streets. The life here is like that of children playing. I swear in all my life I have never had such ravishing sensations of exquisite art-joy, of pure, delicious enthusiasm for the physical, exterior aspect of a city. It is as mild and sweet as moonlight itself.

* * * * *

This hotel, Royal Danieli, is a delicious old palace, laved on one side by a canal. My room commands the whole of the Lagoon. George Sand and Alfred de Musset occupied a room here somewhere. Perhaps I have it.

* * * * *

Venice is so markedly different from Florence. There all is heavy, somber, defensive, serious. Here all is light, airy, graceful, delicate. There could be no greater variation. Italy is such a wonderful country. It has Florence, Venice, Rome and Naples, to say nothing of Milan and the Riviera, which should really belong to it. No cornices here in Venice. They are all left behind in Florence.

* * * * *

What shall I say of St. Mark’s and the Ducal Palace—mosaics of history, utterly exquisite. The least fragment of St. Mark’s I consider of the utmost value. The Ducal Palace should be guarded as one of the great treasures of the world. It is perfect.

* * * * *

There can only be one Venice

Fortunately I saw St. Mark’s in the morning, in clear, refreshing, springlike sunlight. Neither Venice nor Florence have the hard glitter of the South—only a rich brightness. The domes are almost gold in effect. The nine frescoes of the façade, gold, red and blue. The walls, cream and gray. Before it is the oblique quadrangle which necessitates your getting far to one side to see the church squarely—a perfect and magnificently individual jewel. All the great churches are that, I notice. Overhead a sky of blue. Before you a great, smooth pavement, crowded with people, the Campanile (just recompleted) soaring heavenward in perfect lines. What a square! What a treasure for a city to have! Momentarily this space is swept over by great clouds of pigeons. The new reproduction of the old Campanile glows with a radiance all its own. Above all, the gilded crosses of the church. To the right the lovely arcaded façade of the library. To the right of the church, facing the square, the fretted beauty of the Doge’s Palace—a portion of it. As I was admiring it a warship in the harbor fired a great gun—twelve o’clock. Up went all my pigeons, thousands it seemed, sweeping in great restless circles while church bells began to chime and whistles to blow. Where are the manufactories of Venice?

* * * * *

At first you do not realize it, but suddenly it occurs to you—a city of one hundred and sixty thousand without a wagon, or horse, without a long, wide street, anywhere, without trucks, funeral processions, street cars. All the shops doing a brisk business, citizens at work everywhere, material pouring in and out, but no wagons—only small barges and gondolas. No noise save the welcome clatter of human feet; no sights save those which have a strange, artistic pleasantness. You can hear people talking sociably, their voices echoed by the strange cool walls. You can hear birds singing high up in pretty windows where flowers trail downward; you can hear the soft lap of waters on old steps at times, the softest, sweetest music of all.

* * * * *

I find boxes, papers, straw, vegetable waste, all cast indifferently into the water and all borne swiftly out to sea. People open windows and cast out packages as if this were the only way. I walked into the Banca di Napoli this afternoon, facing the Grand Canal. It was only a few moments after the regular closing hour. I came upon it from some narrow lane—some “dry street.” It was quite open, the ground floor. There was a fine, dark-columned hall opening out upon the water. Where were the clerks, I wondered? There were none. Where that ultimate hurry and sense of life that characterizes the average bank at this hour? Nowhere. It was lovely, open, dark,—as silent as a ruin. When did the bank do business, I asked myself. No answer. I watched the waters from its steps and then went away.

* * * * *

One of the little tricks of the architects here is to place a dainty little Gothic balcony above a door, perhaps the only one on the façade, and that hung with vines.

* * * * *

Venice is mad about campaniles. It has a dozen, I think, some of them leaning, like the tower at Pisa.

* * * * *

I must not forget the old rose of the clouds in the west.

* * * * *

A gondolier selling vegetables and crying his wares is pure music. At my feet white steps laved by whitish-blue water. Tall, cool, damp walls, ten feet apart. Cool, wet, red brick pavements. The sun shining above makes one realize how lovely and cool it is here; and birds singing everywhere.

* * * * *

Gondolas doing everything, carrying casks, coal, lumber, lime, stone, flour, bricks, and boxed supplies generally, and others carrying vegetables, fruit, kindling and flowers. Only now I saw a boat slipping by crowded with red geraniums.

* * * * *

Lovely pointed windows and doors; houses, with colonnades, trefoils, quadrifoils, and exquisite fluted cornices to match, making every house that strictly adheres to them a jewel. It is Gothic, crossed with Moorish and Byzantine fancy. Some of them take on the black and white of London smoke, though why I have no idea. Others being colored richly at first are weathered by time into lovely half-colors or tones.

* * * * *

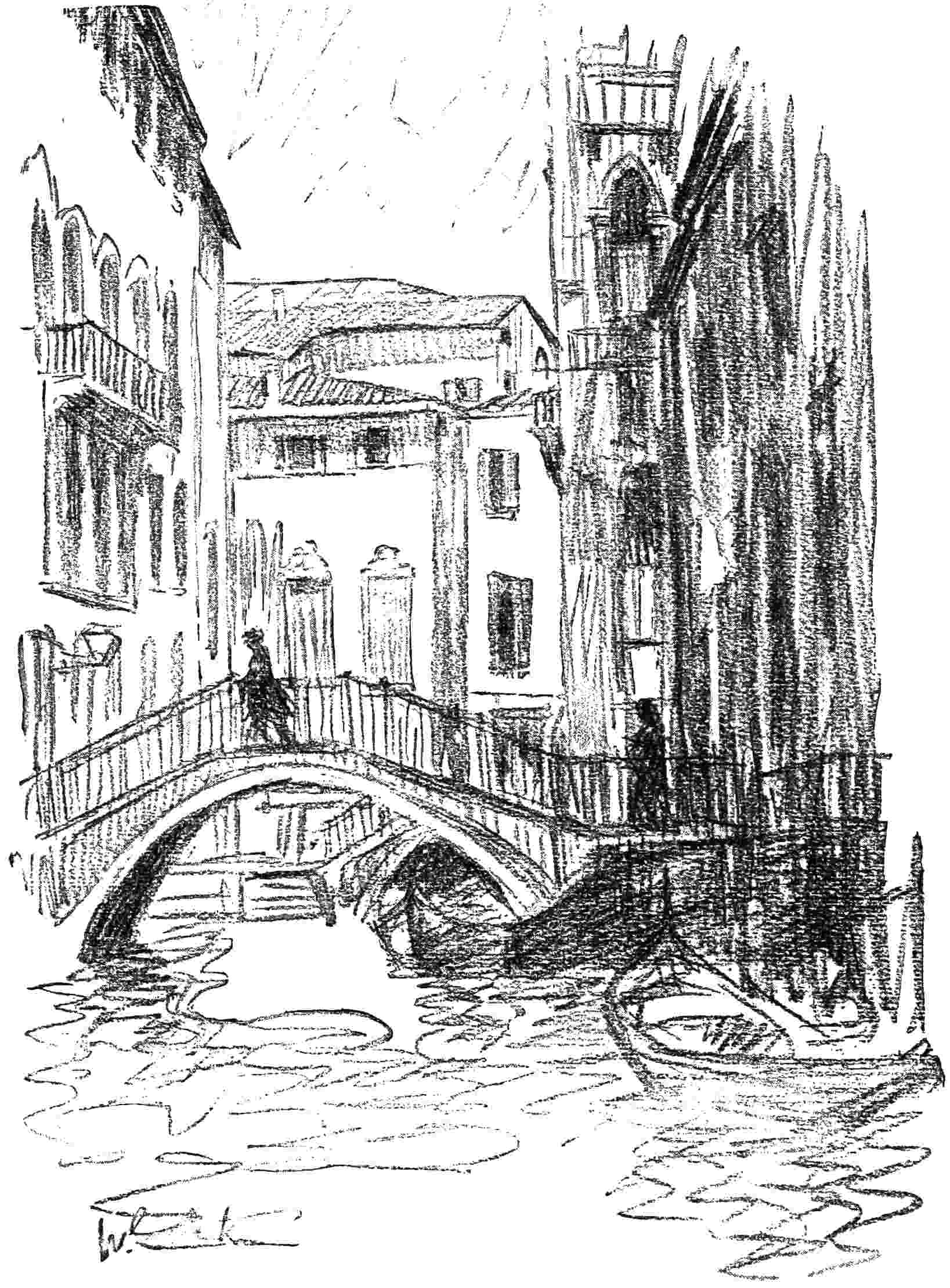

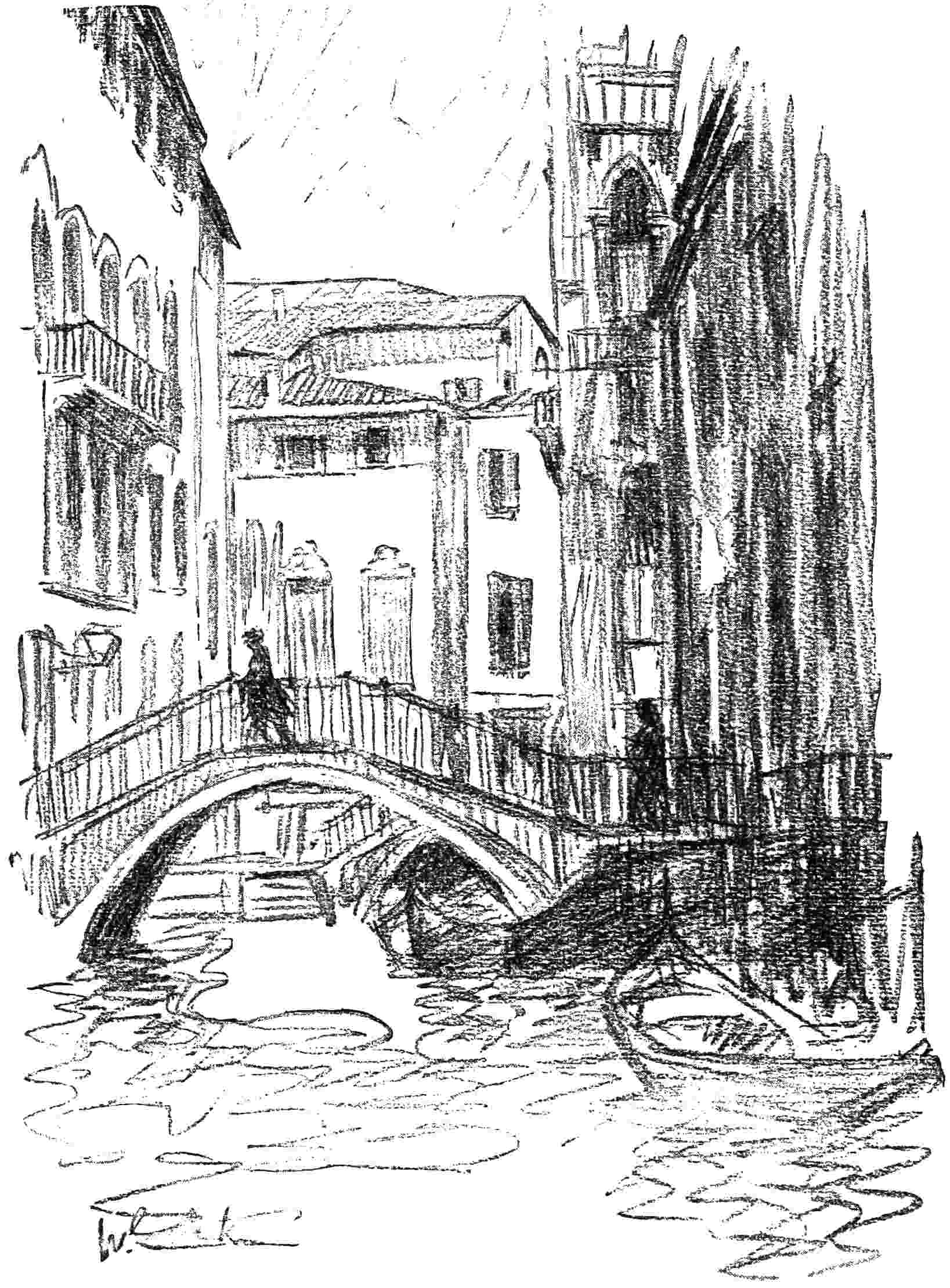

These little canals are heavenly! They wind like scattered ribbons, flung broadcast, and the wind touches them only in spots, making the faintest ripples. Mostly they are as still as death. They have exquisite bridges crossing in delightful arches and wonderful doors and steps open into them, steps gray or yellow or black with age, steps that have green and brown moss on them and that are alternately revealed or hidden by a high or low tide. Here comes a gondolier now, peddling oranges. The music of his voice!

* * * * *

Latticework is everywhere, and it so obviously belongs here. Latticework in the churches, the houses, the public buildings. Venice loves it. It is oriental and truly beautiful.

* * * * *

I find myself at a branch station of the water street-car service. There are gondolas here, too,—a score for hire. This man hails me genially, his brown hands and face, and small, old, soft roll hat a picture in the sun. I feel as if I were dreaming or as if this were some exquisite holiday of my childhood. One could talk for years of these passages in which, amidst the shadow and sunlight of cool, gray walls a gleam of color has shown itself. You look down narrow courts to lovely windows or doors or bridges or niches with a virgin or a saint in them. Now it is a black-shawled housewife or a fat, phlegmatic man that turns a corner; now a girl in a white skirt and pale green shawl, or a red skirt and a black shawl. Unexpected doorways, dark and deep with pleasant industries going on inside, bakeries with a wealth of new, warm bread; butcheries with red meat and brass scales; small restaurants, where appetizing roasts and meat-pies are displayed. Unexpected bridges, unexpected squares, unexpected streams of people moving in the sun, unexpected terraces, unexpected boats, unexpected voices, unexpected songs. That is Venice.

* * * * *

To-day I took a boat on the Grand Canal to the Giardino which is at the eastern extreme of the city. It was evening. I found a lovely island just adjoining the gardens—a Piazza d’Arena. Rich green grass and a line of small trees along three sides. Silvery water. A second leaning tower and more islands in the distance. Cool and pleasant, with that lovely sense of evening in the air which comes only in spring. They said it would be cold in Venice, but it isn’t. Birds twittering, the waters of the bay waveless, the red, white and brown colors of the city showing in rich patches. I think if there is a heaven on earth, it is Venice in spring.

* * * * *

Just now the sun came out and I witnessed a Turner effect. First this lovely bay was suffused with a silvery-gold light—its very surface. Then the clouds in the west broke into ragged masses. The sails, the islands, the low buildings in the distance began to stand out brilliantly. Even the Campanile, San Giorgio Maggiore and the Salute took on an added glory. I was witnessing a great sky-and-water song, a poem, a picture—something to identify Venice with my life. Three ducks went by, high in the air, honking as they went. A long black flotilla of thin-prowed coal barges passed in the foreground. The engines of a passing steamer beat rhythmically and I breathed deep and joyously to think I had witnessed all.

* * * * *

Bells over the water, the lap of waves, the smell of seaweed. How soft and elevated and ethereal voices sound at this time. An Italian sailor, sitting on the grass looking out over it all, has his arms about his girl.

* * * * *

It would be easy to give an order for ten thousand lovely views of Venice, and get them.

* * * * *