CHAPTER VII

OUR FIRST NIGHT IN THE UNDER WORLD, AND HOW IT WAS FOLLOWED BY THE FIRST BREAK OF DAY.—BULGER’S WARNING AND WHAT IT MEANT.—WE FALL IN WITH AN INHABITANT OF THE WORLD WITHIN A WORLD.—HIS NAME AND CALLING.—MYSTERIOUS RETURN OF NIGHT.—THE LAND OF BEDS, AND HOW OUR NEW FRIEND PROVIDED ONE FOR US.

So heavy with sleep did my eyelids become at last that I knew that it must be night in the outer world, and so we halted, and I stretched myself at full length on that marble floor, which, by the way, was pleasantly warm beneath us; and the air, too, was strangely comforting to the lungs, there being a complete absence of that smell of earth and odor of dampness so common in vast subterranean chambers.

My sleep was long-continued and most refreshing; Bulger was already awake, however, when I sat up and tried to look about me.

He began tugging at the string which I had fastened to his collar as if he wanted to lead me somewhere, so I humored him and followed along after. To my delight he led me straight to a pool of deliciously sweet and cold water. Here we drank our fill, and after a very frugal breakfast on some dried figs set out again on our journey along the Marble Highway. Suddenly, to my more than joy, the faint and uncertain light of the place began to strengthen. Why, it seemed almost as if the day of the upper world were about to break, so delicate were the various hues in which the ever-increasing light clothed itself: then, as if affrighted at its own increasing glory, it would fade away again to almost gloom. Ere many moments again this faint and mysterious glow would return, beginning with the softest yellow, then changing through a dozen different tints, and, like a fickle maid uncertain which to wear, put all aside and don the lily’s garb. Bulger and I wandered along the Marble Highway almost afraid to break a stillness so deep that it seemed to me as if I could hear those sportive rays of light in their play against the many-colored rocks arching this mighty corridor.

Now, as the Marble Highway swept around in a graceful curve, a dazzling flood of light burst upon us.

It was sunrise in the World within a World.

Whence came this flood of dazzling light which now caused the sides and arching roof to glow and sparkle as if we had suddenly entered one of Nature’s vast storehouses of polished gems? Shading my eyes with my hand I looked about me in order to try and solve the mystery.

It did not take me long to understand it all. Know then, dear friends, that the ceilings, domes, and arched roofs of this underground world were fretted with a metal of greater hardness than any known to us children of sunshine. Its seams ran hither and thither like the veins of gigantic leaves; and at certain hours currents of electricity from some vast internal reservoir of Nature’s own building, streamed through these metal traceries until they glowed with a heat so white as to give off the flood of dazzling light of which I have already spoken.

The current never came with a sudden rush or burst, but began gently and timidly, so to speak, as if feeling its way along. Hence the beautiful tints that always preceded sunrise in this lower world, and made it so much like the coming and going of our glorious sunshine.

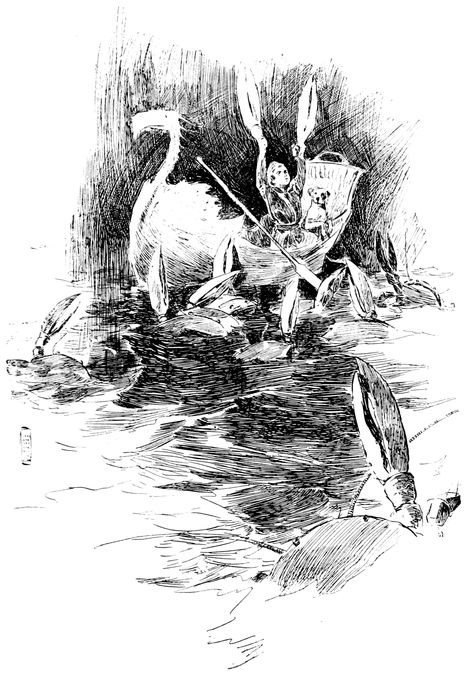

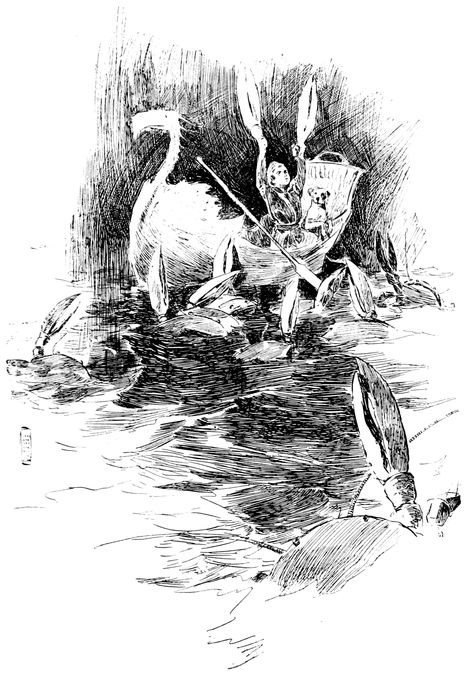

The Marble Highway now divided, and the two halves of the fork curving away to the right and left enclosed a small but exquisitely ornamented park, or pleasure ground I might call it, provided with seats of some dark wood beautifully polished and carved. This park was ornamented with four fountains, each springing from a crystal basin and spreading out into a feathery spray that glistened like whirling snow in the dazzling white light. As Bulger and I directed our steps toward one of the benches with the intention of taking a good rest, a low growl from him warned me to be on the alert. I gave a second look. A human being was seated on the bench. Beside myself, as I was, with curiosity to come face to face with this inhabitant of the under world, the first we had met, I made a halt, determined to ascertain, if possible, whether he was quite harmless before accosting him.

He was small in stature, and clad entirely in black, a sort of loose, flowing robe much like a Roman toga. His head was bare, and what I could see of it was round, smooth, and rosy, with about as much hair, or rather fuzz, upon it as the head of an infant six weeks old. His face was hidden by a black fan which he carried in his right hand, and the uses of which you will learn later on. His eyes were shielded from the intense glare of the light by a pair of colored glass goggles. As he raised his hand between me and the light I couldn’t help catching my breath. I could see right through it: the bones were as clear as amber. And his head, too, was only a little less opaque. Suddenly two words from Don Fum’s manuscript flashed through my mind, and I exclaimed joyously,—

“Bulger, we’re in the Land of the Transparent Folk!”

At the sound of my voice the little man arose and made a low bow, lowering his fan to his breast where he held it. His baby face was ludicrously sad and solemn.

“Yes, Sir Stranger,” said he, in a low, musical voice, “thou art indeed in the Land of the Mikkamenkies (Mica Men), in the Land of the Transparent Folk, called also Goggle Land; but if I should show thee my heart thou wouldst see that I am deeply pained to think that I should have been the first to bid thee welcome, for know, Sir Stranger, that thou speakest with Master Cold Soul the Court Depressor, the saddest man in all Goggle Land, and, by the way, sir, permit me to offer thee a pair of goggles for thyself, and also a pair for thy four-footed companion, for our intense white light would blind thee both in a few days.”

I thanked Master Cold Soul very warmly for the goggles, and proceeded to set one pair astride my nose and to tie the other in front of Bulger’s eyes. I then in most courteous manner informed Master Cold Soul who I was, and begged him to explain the cause of his great sadness. “Well, thou must know, little baron,” said he, after I had taken a seat beside him on the bench, “that we, the loving subjects of Queen Galaxa, whose royal heart is almost run down,—excuse these tears, living as we do in this beautiful world so unlike the one you inhabit, which our wise men tell us is built, strange to say, on the very outside of the earth’s crust where it is most exposed to the full sweep of blinding snow, freezing blast, pelting hail, drowning rain, and choking dust,—living as we do, I say, in this vast temple by Nature’s own hands builded, where disease is unknown, and where our hearts run down like clocks that may have but one winding, we are prone, alas, to be too happy; to laugh too much; to spend too much time in idle gayety, chattering the time away like thoughtless children amused with baubles, delighted with tinsel nothings. Know then, little baron, that mine is the business to check this gayety, to put an end to this childish glee, to depress our people’s spirits, lest they run too high. Hence my garb of inky hue, my rueful countenance, my frequent outflowing of tears, my voice ever attuned to sadness. Excuse me, little baron, my fan slipped then; didst see through me? I would not have thee see my heart to-day, for some way or other I cannot bring it to a slow pace; it is dreadfully unruly.”

I assured him that I had not seen through him as yet.

And now, dear friends, I must explain that by the laws of the Mikkamenkies each man, woman, and child must wear in their garments a heart-shaped opening on their breast directly over their hearts, with a corresponding one at the back, so that under certain conditions, when the law allows it, each may have the right to take a look at his neighbor’s heart and see exactly how it is beating—whether fast or slow, whether throbbing or leaping, or whether pulsating calmly and naturally. But this privilege is only accorded, as I have said, under certain conditions, hence to shut off inquisitive glances each Mikkamenky is allowed to carry a black fan with which to cover the heart-shaped opening above described, and in this way conceal his or her feelings to a degree. I say to a degree, for I may as well tell you right here that falsehood is unknown, or, more correctly stated, impossible in the land of the Transparent Folk, for the reason that so wondrously clear, limpid, and crystal-like are their eyes that the slightest attempt to say one thing while they are thinking another roils and clouds them as if a drop of milk had fallen into a glass of the purest water.

As I sat gazing at this strange little being seated on the bench there beside me, I recalled a conversation which I had had with a learned Russian at Solvitchegodsk. Said he, speaking of his people, “We are all born with light hair, brilliant eyes, and pale faces, for we have sprung up under the snow.” And I thought to myself how delighted, how entranced, he would have been to look upon this curious being, born not under the snow, but far under the surface of the earth, where in these vast chambers of this World within a World, this strange folk had, like plants grown in a dark, deep cellar, gradually parted with all their coloring until their eyes glowed like orbs of pure crystal, until their bones had been bleached to amber clearness, and their blood coursed colorless through colorless veins. While sitting there following out this train of thought, the clear white light suddenly began to flicker and to play fantastic tricks upon the walls by dancing in garbs of ever-changing hues, now brightest yellow, now palest green, now glorious purple, now deepest crimson.

“Ah, little baron!” exclaimed Master Cold Soul, “that was an uncommonly short day. Rise, please.”

I made haste to obey, whereupon he touched a spring and the bench opened in the centre, disclosing two very comfortable beds.

A DINNER EASILY PROVIDED FOR.

“In a few moments night will be upon us,” continued the Mikkamenky, “but thou seest that we have not been taken by surprise. I should explain to thee, little baron, that owing to the capricious manner in which our River of Light is apt both to begin and to cease flowing, we are never able to tell how long a day or a night will prove to be. This is what we call twilight. In thy world I suppose day goes out with a terrible bang, for our wise men tell us that nothing can be done in the upper world without making a noise; that your people really love noise; and that the man who makes the greatest noise is considered the greatest man.

“Owing to the fact, little baron, that no one in Goggle Land can tell how long the day will last, or how long it may be necessary to sleep, our laws permit no one to set any exact time when a thing shall be done, or to exact any promise to do this or that on a certain day, for, bless thy soul, that day may not be ten minutes long. Hence we say, ‘If to-morrow be over five hours long, come to me at the beginning of the sixth hour;’ and we never wish each other a plain good-night, but say, ‘Good-night, as long as it lasts.’

“What’s more, little baron, as night is apt to come upon us this way unawares, by law all the beds belong to the state; no one is allowed to own his own bed, for when night overtakes him he may be at the other end of the city, and some other subject of Queen Galaxa may be in front of his door, and no matter where night may overtake a Mikkamenky, he is sure to find a bed. There are beds everywhere. By touching a spring they drop from the walls, they pull out like drawers, they are under the tables and divans, in the parks, in the market-place, by the roadside; benches, bins, boxes, barrows, and barrels by pressing a spring may in an instant be transformed into beds. It is the Land of Beds, little baron. But ah! behold, the twilight goes to its end. Good-night as long as it lasts!” and with this Master Cold Soul stretched himself out and began to snore, having first carefully covered up the two holes in the front and back of his garment, so that I shouldn’t have a chance to take a peep through him in case I should wake up first. Bulger and I were right glad to lay our limbs on a real bed, although from the way my four-footed brother followed his tail around and around, I could see that he wasn’t particularly delighted with the softness of the couch.