CHAPTER XI

PLEASANT DAYS PASSED AMONG THE MIKKAMENKIES, AND WONDERFUL THINGS SEEN BY US.—THE SPECTRAL GARDEN, AND A DESCRIPTION OF IT.—OUR MEETING WITH DAMOZEL GLOW STONE, AND WHAT CAME OF IT.

From now on Lord Bulger and I made ourselves perfectly at home among the Mikkamenkies. One of the royal barges was placed at our disposal, and when we grew tired of walking about and gazing at the wonders of this beautiful city of the under world, we stepped aboard our barge and were rowed hither and thither on the glassy river; and if I had not seen it myself I never would have believed that any kind of shellfish could ever be taught to be so obliging as to swim to the surface and offer one of their huge claws for our dinner, politely dropping it in our hand the moment we had laid hold of it. On one of the river banks I noticed a long row of wooden compartments looking very much like a grocer’s bins; but you may think how amused Bulger and I were upon coming closer to this long row of little houses to find that they were turtle nests, and that quite a number of the turtles were sitting comfortably in their nests busy laying their eggs—which, let me assure you, were the most dainty tidbits I ever tasted.

I think I informed you that the river flowing through Goggle Land was fairly swarming with delicious fish, the carp and sole being particularly delicate in flavor; and knowing, as I did, what a tender-hearted folk the Mikkamenkies are, I had been not a little puzzled in my mind as to how they had ever been able to summon up courage enough to drive a spear into one of these fish, which were as tame and playful as a lot of kittens or puppies, and followed our barge hither and thither, snapping up the food we tossed to them, and leaping into the air, where they glistened like burnished silver as the white light sparkled on their scales.

But the mystery was solved one day when I saw one of the fishermen decoying a score or more of fish into a sort of pen shut off from the river by a wire netting. Scarcely had he closed the gates when, to my amazement, I saw the fish one after the other come to the surface and float about on their sides, stone dead.

“This, little baron,” explained the man in charge, “is the death chamber. Hidden at the bottom of this dark pool lie several electric eels of great size and power, and when our people want a fresh supper of fish we simply open these gates and decoy a shoal of them inside by tossing their favorite food into the water. The executioners are awaiting them, and in a few instants the fish, while enjoying their repast and suspecting no harm, are painlessly put to death, as thou hast seen.”

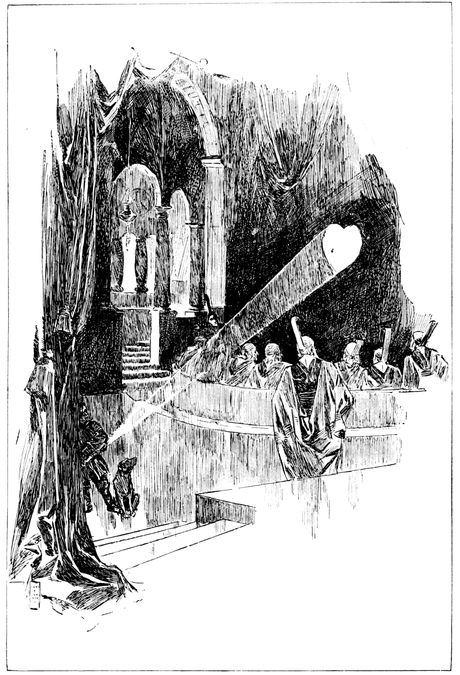

One part of the city of the Transparent Folk which attracted Bulger and me very much was the royal gardens. It was a weird and uncanny place, and upon my first visit I walked through its paths and beneath its arbors upon my toes and with bated breath, as you might steal into some bit of fairy-land, looking anxiously from side to side as if at every step you expected some sprite or goblin to trip you up with a tough spider-web, or brush your cheeks with their cold and satiny wings.

Now, dear friends, you must first be told that with the loss of sunshine and the open air, the flowers and shrubs and vines of this underground world gradually parted with their perfumes and colors, their leaves and petals and stems and tendrils growing paler and paler in hue, like lovelorn maids whose sweethearts had never come back from the war. Month by month the dark greens, the blush pinks, the golden yellows, and the deep blues pined away, longing for the lost sunshine and the wooing breeze they loved so dearly, until at last the transformation was complete, and there they all stood or hung bleached to utter whiteness, like those fantastic clumps of flowers and wreaths of vines which the feathery snow of April builds in the leafless shrubs and trees.

I cannot tell you, dear friends, what a strange feeling came over me as I stepped within this spectral garden where ghost-like vines clung in fantastic forms and figures to the dark trellises, and where tall lilies, whiter than the down of eider, stood bolt upright like spirits doomed to eternal silence, denied even the speech of perfume, and where huge clusters of snowy chrysanthemums, fluffy feathery forms, seemed pressing their soft bodies together like groups of banished celestials in a sort of silent despair as they felt the warmth and glow of sunlight slowly and gradually quitting their souls; where lower down, great roses with snowy petals whiter than the sea-shells hung motionless, bursting open with eager effort, as if listening for some signal that would dissolve the spell put upon them, and give them back the sunshine, and with it their color and their perfume; where lower still beds of violets bleached white as fleecy clouds seemed wrapt in silent sorrow at loss of the heavenly perfume which had been theirs on earth; where, above the lilies’ heads shot long, slender, spectral stalks of sunflowers almost invisible, loaded at their ends with clusters of snowy flowers thus suspended like white faces looking down through the silent air, and waiting, waiting for the sunshine that never came; and higher still all over and above these spectral flowers, intwining and inwrapping and falling festoon and garland-wise, crept and ran like unto long lines of escaping phantoms, ghostly vines with ghostly blossoms, bent and twisted and wrapped and coiled into a thousand strange and fantastic forms and figures which the white light with its inky shadows made alive and half human, so that movement and voice alone were needful to make this garden seem peopled with sorrowing sprites banished to these subterranean chambers for strange misdeeds done on earth and condemned to wait ten thousand years ere sunlight and their color and their perfume should be given back to them again.

While strolling through the royal gardens one day, Bulger suddenly gave a low cry and bounded on ahead, as if his eyes had fallen upon the familiar form of some dear friend.

When I came up with him he was crouching beside the damozel Glow Stone who, seated on one of the garden benches, was caressing Bulger’s head and ears with one of her soft hands with its filmy-like skin, while the other held its black fan pressed tightly against her bosom.

She looked up at me with her crystal eyes, and smiled faintly as I drew near.

“Thou seest, little baron,” she murmured, “Lord Bulger and I have not forgotten each other.” Since our presentation at court I had been going through and through my mind in search of some reason for Bulger’s sudden affection for damozel Glow Stone, but had found none.

I was the more perplexed as she was but the maid of honor, while the fair princess Crystallina sat on the very steps of the throne.

But I said nothing save to reply that I was greatly pleased to see it and to add that where Bulger’s love went, mine was sure to follow.

“Oh, little baron, if I could but believe that!” sighed the fair damozel.

“Thou mayst,” said I, “indeed thou mayst.”

“Then, if I may, little baron,” she replied, “I will, and prithee come and sit beside me here, only till I bid thee, look not through me. Dost promise?”

“I do, fair damozel,” was my answer.

“And thou, Lord Bulger, lie there at my feet,” she continued, “and keep thy wise eyes fixed upon me and thy keen ears wide open.”

“Little baron, if both thine and our worlds were filled with sorrowing hearts, mine would be the heaviest of them all. List! oh, list to the sad, sad tale of the sorrowing maid with the speck in her heart, and, when thou knowest all, give me of thy wisdom.”

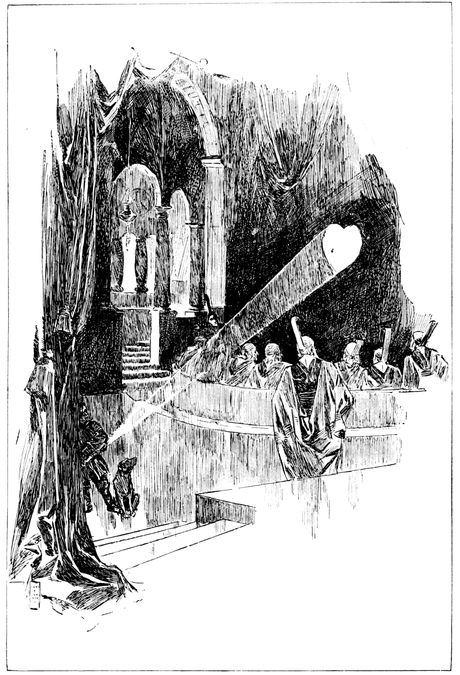

CRYSTALLINA’S HEART ON A SCREEN.