CHAPTER XXI

HOW WE WERE LIGHTED ON OUR WAY DOWN THE DARK AND SILENT RIVER.—SUDDEN AND FIERCE ONSLAUGHT UPON OUR BEAUTIFUL BOAT OF SHELL.—A FIGHT FOR LIFE AGAINST TERRIBLE ODDS, AND HOW BULGER STOOD BY ME THROUGH IT ALL.—COLD AIR AND LUMPS OF ICE.—OUR ENTRY INTO THE CAVERN WHENCE THEY CAME.—THE BOAT OF SHELL COMES TO THE END OF ITS VOYAGE.—SUNLIGHT IN THE WORLD WITHIN A WORLD, AND ALL ABOUT THE WONDERFUL WINDOW THROUGH WHICH IT POURED, AND THE MYSTERIOUS LAND IT LIGHTED.

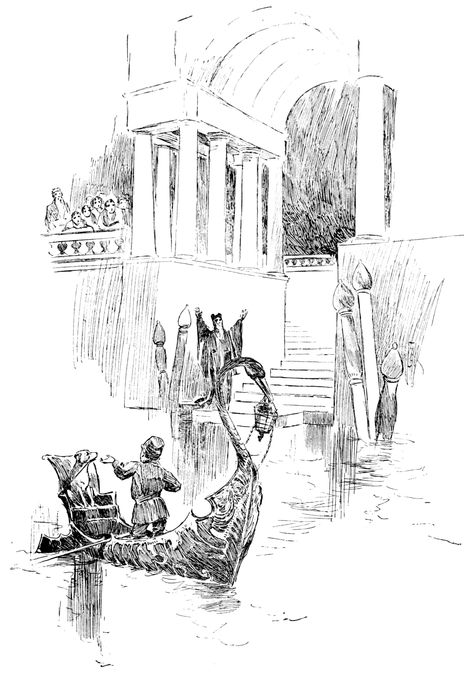

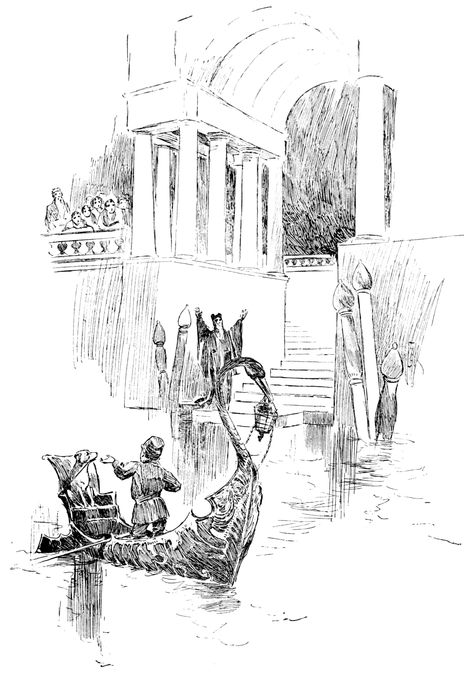

I dare say, dear friends, that you are puzzling your brains to think out how it was possible for me to row away from the wonderful city of the Formifolk without running our boat continually ashore. Ah, you forget that the keen-eyed Bulger was at the helm, and that it was not the first time that he had piloted me through darkness impenetrable to my eyes; but more than this: I soon discovered that the plashing of my silver oars kept my little friends, the fire lizards, in a constant state of alarm, and although I couldn’t hear the crackling of their tails, yet the tiny flashes of light served to outline the shore admirably. So I pulled away with a will, and down this dark and silent river, for there was a current, although hardly perceptible, Bulger and I were borne along in the beautiful bark of tortoise shell with its prow of carved and burnished silver.

During my sojourn in the Land of the Soodopsies I had one day, while calling upon the learned Barrel Brow, noticed a beautifully carved silver hand-lamp of the Pompeian pattern among his curiosities. I asked him if he knew what it was. He replied that he did, adding that it had doubtless been brought from the upper world by his people, and he begged me to accept it as a keepsake. I did so, and upon leaving the City of Silver, I filled it with fish-oil and fitted a silken wick to it. It was well that I had done so, for after a while the fire lizards disappeared entirely, and Bulger and I would have been left in total darkness, had I not drawn forth my beautiful silver lamp, lighted it, and suspended it from the beak of the silver swan which curved its graceful neck above the bow of our boat.

After lying on my oars long enough to set some food before Bulger and partake of some myself, I again started on my voyage down the silent river, no longer shrouded in impenetrable gloom.

I had not taken over half a dozen strokes, when suddenly one of my oars was almost twisted out of my hand by a vicious tug, from some inhabitant of these dark and sluggish waters. I resolved to quicken my stroke in order to escape another such a wrench, for the silver oars fashioned by the Soodopsies for me were of very delicate make, intended only for very gentle usage. Suddenly another vicious snap was made at my other oar; and this time the animal succeeded in retaining its hold, for I dared not attempt to wrench the oar out of its grip, for fear of breaking it. It was a large crustacean of the crab family, and its milk-white shell gave it a ghost-like look as it struggled about in the black waters, fiercely intent to keep its hold upon the oar. The next instant a similar creature had fastened firmly upon my other oar, and there I sat utterly helpless. But worse than this, the dark waters were now fairly alive with these white armored guards of this underworld stream, each apparently bent upon setting an immediate end to my progress through their domain. They now began a series of furious efforts to lay hold of the sides of my boat with their huge claws, but happily its polished surface made this impossible for them to accomplish.

Up to this moment Bulger had not stirred a muscle or uttered a sound, but now a sharp growl from him told me that something serious had happened at his end of the boat. It was serious indeed, for several of the largest of the fierce crustaceans had laid hold of the rudder and were wrenching it from side to side as if to tear it off. Every attempt of course caused a tug at the tiller-ropes held between Bulger’s teeth; but, bracing himself firmly, he resisted their furious efforts as well as he could, and succeeded in saving the rudder for the time being.

All of a sudden our frail bark of shell crashed into some sort of obstruction, and came to a dead standstill. Peering into the darkness, to my horror I saw that the wily enemy had spanned the river with chains made up of living links by each laying hold of his neighbor’s claw, the chain thus formed being then rendered almost as strong as steel by the interweaving of their double rows of small hooked legs.

Our advance was not only blocked, but death, an awful death, seemed to be staring us in the face; for what possible hope of escape could there be if Bulger and I should leap into the water, now alive with these fast swimming creatures, whirling their huge claws about in search for some way to get at us. From the brave manner in which Bulger was holding the madly swinging helm, I saw that he was determined not to surrender. But alas, bravery is but a sorry thing for two to fight a thousand with! And yet I had not lost my head—don’t think that. True, I was hard pressed; the very dust of the balance, if thicker on their side, might make my scale kick the beam.

I had hauled both oars into the boat by reaching over and beating off the claws fastened upon them, and had up to this moment driven back every one of the fierce creatures which had succeeded in throwing one of his claws over the edge of the boat; but now, to my horror, I felt that our little craft was being slowly but surely drawn stern first toward the river bank. In order to accomplish this, the crustaceans had thrown out a line composed of their bodies gripped together, and had made it fast to the rudder. Not an instant was to be lost!

Once upon the river bank, the fierce creatures would swarm around us by the tens of thousands, drag us down, pinch us to death, and tear us piecemeal!

SAILING AWAY FROM THE LAND OF THE SOODOPSIES.

An idea flashed upon me—it was this: it is folly to attempt to resist these countless swarms of crustaceans by the use of one pair of weak hands, even though they be aided by Bulger’s keen and willing teeth. We should, after a brief struggle, go down as the brave man in the sewer went down, when the famished rats leaped upon him from every side at once, or as the stray buffalo goes down when the pack of ravenous wolves closes up its circle about him. If I am to save my life, it must be by striking a blow that will reach every one of these small but fierce enemies at the same instant, and thus paralyze them, or, at least, bewilder them, until I can succeed in making my escape!

Quickly drawing my brace of pistols, I held their muzzles close to the water, and discharged them at the same instant. The effect was terrific. Like a crash of a terrible thunderbolt, the report burst forth and echoed through these vast and silent chambers, until it seemed as if the great vaulted roof of rock had by some awful convulsion of nature been cast roaring and rattling down upon the face of these black and sluggish waters! When the smoke had cleared away, a strange but welcome sight met my gaze. Tens of thousands of the huge crabs floated lifeless upon the surface of the river, with their shells split by the concussion the full length of their bodies.

It proved to have been a masterly stroke on my part, and, dear friends, you will believe me when I tell you that I drew a deep breath as I set my silver oars against the thole-pins, and, having worked my boat clear of the swarms of stunned crustaceans, rowed away for dear life!

Dear life! Ah, yes, dear life, for whose life is not dear to him, even though it be dark and gloomy at times? Is there not always something, or some one, to live for? Is there not always a glimmer of hope that the morrow’s sun will go up brighter than it did this morning? Well, anyway, I repeat that I rowed away for dear life, while Bulger held the tiller-ropes and kept our frail bark of polished shell in the middle of the stream.

Whether the air was actually colder, or whether it was merely the natural chill that so often strikes the human heart after it has been beating and throbbing with alternate hope and fear, I couldn’t say at the time; but I knew this much, that I suddenly found myself suffering from the cold.

For the first time since my descent into the World within a World, the air nipped my finger-tips; that soft, balmy, June-like atmosphere was gone, and I made haste to put on my fur-trimmed top-coat, which I had not made much use of lately.

At that moment one of my oars struck against some hard substance floating in the waters. I put out my hand to feel of it. To my great surprise it proved to be a lump of ice, and very soon another and another went floating by us.

We were most surely entering a region where it was cold enough to make ice. I was not sorry for this; for, to tell the truth, Bulger and I were both beginning to feel the effects of our long sojourn in the rocky chambers of this under world, whose atmosphere, though soft and warm, yet lacked the elasticity of the open air.

Ice caverns would be a complete change, and the cold air would, no doubt, send our blood tingling through our veins just as if we were out a-sleighing in the upper world on a winter’s night, when the stars twinkle over our heads and the snow crystals creak beneath our runners.

Soon now huge icicles began to dot the roof of rock that spanned the river, and shafts and columns of ice dimly visible along the shore seemed to be standing there like silent sentries, watching our boat as it threaded its way through the ever-narrowing channel. And now, too, a faint glow of light reached us from I knew not where, so that by straining my eyes I could see that the river had taken a sweep, and entered a vast cavern with roof and walls of ice fretted and carved into fantastic depths and niches and shelves and cornices, with here and there shapes so fanciful that it seemed to me I had entered some vast hall of statuary, where hero and warrior, nymph and maiden, shepherd and bird-catcher, filled these shelves and niches in glorious array. Farther advance by water was impossible, for the blocks of ice, knitted together like a floe, closed the river completely. I therefore determined to make a landing—draw my boat upon the shore, and continue my journey on foot.

The mysterious light which up to this moment had shed its pale glimmer like an arctic night upon the roofs and walls of ice of these silent chambers now began to strengthen so that Bulger and I had no difficulty in picking our way along the shore. In fact, we crossed and recrossed the river itself when the whim seized us, for it now went winding on ahead of us, like a broad ribbon of ice through caverns and corridors.

Suddenly I came to a halt and stood as motionless as the fantastic forms of ice surrounding me. What could it mean? Were my eyes weakened by my long sojourn in the World within a World, playing me cruel tricks? Surely there can be no mistake! I whispered to myself. That light yonder which pours its glorious effulgence upon those spires and pinnacles, those towers and turrets of ice, is the sunshine of the upper world! Can it be that my marvellous underground journey is ended, that I stand upon the threshold of the upper world once more?

Bulger, too, recognizes this flood of sunshine, and breaking out into a fit of joyous barking, dashes on ahead, to be the first one to feel its gentle warmth after our long journey through the dark and silent passages of the World within a World.

But I dare not trust my eyes, and fearing lest he should fall into some ambush or meet with some dread accident, I called him back to me.

Together we hurry along as rapidly as possible. Now I note that we are drawing near to the end of the vast corridor through which we have been making our way for some time, and that we stand upon the portal of a mighty subterranean region lighted with real sunlight. It stretches away as far as the eye can reach, and so high is the roof that spans this vast under world that I cannot see whether it be of ice or not. All that I can see is that through one of its sloping sides there streams a mighty torrent of sunlight, which pours its splendor with unstinting hand upon the wide highways, the broad terraces, the sheer parapets, and the sloping banks which diversify this ice world. Can it be that one side of this mighty mountain which nature has here hollowed out and set like a peaked roof over this vast subterranean region, is a gigantic window of ice itself through which the sunlight of the outer world streams in this grand way like a silent cataract of light, like a deluge of sunshine? No, this could not be; for now upon a second look I saw that this flood of light thus streaming through the side of the mountain came through it like a mighty pencil of rays, and striking the opposite walls with its brilliancy a hundred-fold increased, rebounded in a thousand directions, flooding the whole region with its effulgence and dying away in faint and pearl-like glimmer in the vast approach where I had first noted it.

And therefore I understood that nature must have set a gigantic lens, twice a thousand feet or more in diameter, in the sloping side of this hollow mountain—a perfect lens of purest rock crystal, which, gathering in its mysterious bosom the sunlight of the outer world, threw it—intensely radiant and dazzling white—into the gloomy depths of this World within a World, so that when the sun went up out there, it went up in here as well, but became cold as it was beautiful, bringing no warmth, no other cheer save light, to this subterranean region which for thousands of centuries had lain locked in the crystal embrace of frozen lakes and brooks and rivers and torrents and waterfalls, once bubbling and flowing and rushing headlong through fair lands of the upper world, but suddenly checked in their course by some bursting forth of mighty pent-up forces, and turned downward into these icy depths condemned to everlasting rest and silence, their crystals locked in a sleep that never would know an awaking, mocked in their dreams by this mysterious sunlight that came with the smile and the fair, winsome look of the real, and yet was so powerless to set them free as once it did when the springtime came in the upper world. All these thoughts and many others besides flitted through my mind as I stood looking up at that mighty lens in its setting of mightier rock.

And so deeply impressed was I by the sight of such a great flood of sunlight pouring through this gigantic bull’s eye which nature had set in the rocky side of the hollow mountain peak and illumining this under world, that the longer I gazed upon the wonderful spectacle the more firmly inthralled my senses became by it.

The deep silence, the deliciously pure air, the ever-varying tints of the light as the mighty ice columns acting the part of prisms, literally filled those vast chambers with the rainbow’s glorious glow, imparted unto the spell resting upon me such unearthly power that it might have held me there until my limbs hardened into icy crystals and my eyes looked out with a frozen stare, had not the ever-watchful Bulger given a gentle tug at the skirt of my coat and aroused me from my inthralling meditation.