CHAPTER IV

MY WOUND HEALS.—YULIANA TALKS ABOUT THE GIANTS’ WELL.—I RESOLVE TO VISIT IT.—PREPARATIONS TO ASCEND THE MOUNTAINS.—WHAT HAPPENED TO YULIANA AND TO ME.—REFLECTION AND THEN ACTION.—HOW I CONTRIVED TO CONTINUE THE ASCENT WITHOUT YULIANA FOR A GUIDE.

It was a day or so before I could walk steadily, and meantime I made unusual efforts to keep my brain quiet, but in spite of all I could do every mention of the Giants’ Well by one of the peasants sent a strange thrill through me, and I would find myself suddenly pacing up and down the floor, and repeating over and over again the words, “Giants’ Well! Giants’ Well!”

Bulger was greatly troubled in his mind, and sat watching me with a most bewildered look in his loving eyes. He had half a suspicion, I think, that that cruel blow from Ivan’s whip-handle had injured my reasoning powers, for at times he uttered a low, plaintive whine. The moment I took notice of him, however, and acted more like myself, he gamboled about me in the wildest delight. As I had directed the peasants to drive Ivan’s horses back towards Ilitch on the Ilitch, until they should meet that miscreant and deliver them to him, I was now without any means of continuing my journey northward, unless I set out, like many of my famous predecessors, on foot. They had longer legs than I, however, and were not loaded with so heavy a brain in proportion to their size, and a brain, too, that scarcely ever slept, at least not soundly. I was too impatient to reach the portals to the World within a World to go trudging along a dusty highway. I must have horses and another tarantass, or at least a peasant’s cart. I must push on. My head was quite healed now, and my fever gone.

“Hearken, little master,” whispered Yuliana; such was the name of the old woman who had taken care of me, “thou art not what thou seemst. I never saw the like of thee before. If thou wouldst, I believe thou couldst tell me how high the sky is, how thick through the mountains are, and how deep the Giants’ Well is.”

I smiled, and then I said,—

“Didst ever drink from the Giants’ Well, Yuliana?”

At which she wagged her head and sent forth a low chuckle.

“Hearken, little master,” she then whispered, coming close to me, and holding up one of her long, bony fingers, “thou canst not trick me—thou knowest that the Giants’ Well hath no bottom.”

“No bottom?” I repeated breathlessly, as Don Fum’s mysterious words, “The people will tell thee!” flashed through my mind. “No bottom, Yuliana?”

“Not unless thine eyes are better than mine, little master,” she murmured, nodding her head slowly.

“Listen, Yuliana,” I burst out impetuously, “where is this bottomless well? Thou shalt lead me to it; I must see it. Come, let’s start at once. Thou shalt be well paid for thy pains.”

“Nay, nay, little master, not so fast,” she replied. “It’s far up the mountains. The way is steep and rugged, the paths are narrow and winding, a false step might mean instant death, were there not some strong hand to save thee. Give up such a mad thought as ever getting there, except it be on the stout shoulders of some mountaineer.”

“Ah, good woman,” was my reply, “thou hast just said that I am not what I seem, and thou saidst truly. Know, then, thou seest before thee the world-renowned traveller, Wilhelm Heinrich Sebastian von Troomp, commonly called ‘Little Baron Trump,’ that though short of stature and frail of limb, yet what there is of me is of iron. There, Yuliana, there’s gold for thee; now lead the way to the Giants’ Well.”

“Gently, gently, little baron,” almost whispered the old peasant woman, as her shrivelled hand closed upon the gold piece. “I have not told thee all. For leagues about, I ween, no living being excepting me knows where the Giants’ Well is. Ask them and they’ll say, “It’s up yonder in the mountains, away up under the eaves of the sky.” That’s all. That’s all they can tell thee. But, little master, I know where it is, and the very herb that cured thy hurt head and saved thee from certain death by cooling thy blood, was plucked by me from the brink of the well!” These words sent a thrill of joy through me, for now I felt that I was on the right road, that the words of the great master of all masters, Don Fum, had come true.

“The people will tell thee!”

Ay, the people had told me, for now there was not the faintest shadow of doubt in my mind that I had found the portals to the World within a World! Yuliana should be my guide. She knew how to thread her way up the narrow pass, to turn aside from overhanging rocks which a mere touch might topple over, to find the steps which nature had hewn in the sides of the rocky parapets, and to pursue her way safely through clefts and gorges, even the entrance to which might be invisible to ordinary eyes. However, in order that the superstitious peasants might be kept friendly to me, I gave it out that I was about to betake myself to the mountains in search of curiosities for my cabinet, and begged them to furnish me with ropes and tackle, with two good stout fellows to carry it for me, promising generous payment for the services.

They made haste to provide me with all I asked for, and we set out for the mountain path at daybreak. Yuliana, in order not to seem to be of the party, had gone on ahead by the light of the moon, telling her people that she wished to gather certain herbs before the sun’s rays struck them and dried the healing dew that beaded their leaves.

ALONG A HIGHWAY OF THE UNDER WORLD.

All went well until the sun was well up over our heads, when suddenly I heard a woman, who proved to be Yuliana, utter a piercing scream. In a moment or so the mystery was solved. The old beldam came rushing down the mountain, her thin wisp of gray hair fluttering in the wind. Her hands were tied behind her, and two young peasants with birchen rods were beating her every chance they got.

“Turn back, turn back, brothers,” they cried to my two men. “The little wizard there has struck hands with this old witch. They’re on their way to the Giants’ Well. They’ll loosen a band of black spirits about our ears. We shall all be bewitched. Quick! Quick! Cast off the loads ye’re bearing and follow us.”

The two men didn’t wait for a second bidding, and throwing the tackle on the ground, they all disappeared like a flash, but for several moments I could hear the screams of poor Yuliana as these young wretches beat the old woman with their birchen rods.

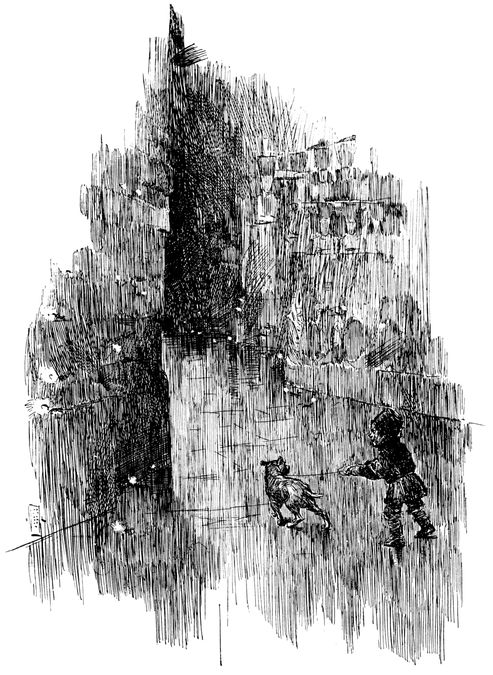

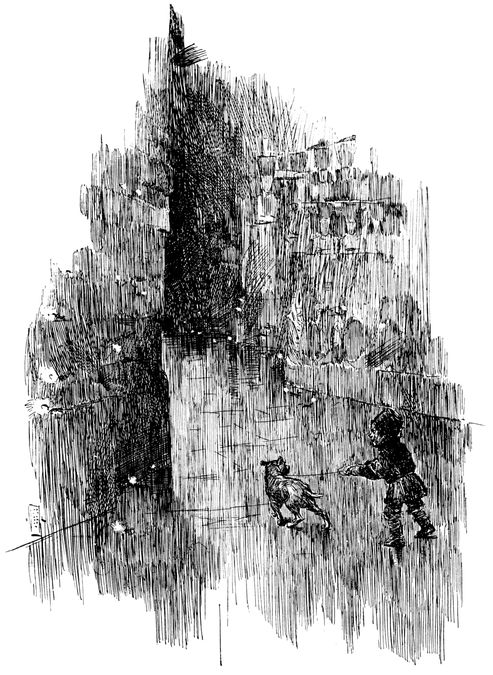

Well, dear readers, what say ye to this? Was I not in a pleasant position truly? Alone with Bulger in that wild and gloomy mountain region, the black rocks hanging like frowning giants and ogres over our heads, with the dwarf pines for hair, clumps of white moss for eyes, vast, gaping cracks for mouths, and gnarled and twisted roots for terrible fingers, ready to reach down for my poor little weazen frame.

Did I fall a-trembling? Did I make haste to follow those craven spirits down the mountain side? Did I shift the peg of my courage a single hole lower?

Not I. If I had I wouldn’t have been worthy of the name I bore. What I did do was to throw myself at full length on a bed of moss, call Bulger to my side, and close my eyes to the outer world.

I have heard of great men going to bed at high noon to give themselves up to thought, and I had often done it myself before I had heard of their doing it.

In fifteen minutes, by nature’s watch—the sun on the face of the mountain—I had solved the problem. Now, there were two difficulties staring me in the face; namely, to find somebody to show me the way up the mountain, and if that body couldn’t carry my tackle, then to find somebody else who could.

It suddenly occurred to me that I had noticed some cattle grazing at the foot of the mountain, and, what’s more, that these cattle wore very peculiar yokes.

“What are those yokes for?” I asked myself, for they were of a make quite different from any that I remembered ever having seen, and consisted of a stout wooden collar from the bottom of which there projected backward between the beast’s forelegs a straight piece of wood armed with an iron spike pointing toward the ground. At the top the yoke was bound by a leather thong to the animal’s horns. So long, therefore, as the beast held his head naturally or even lowered it to graze, the yoke was drawn forward and the hook was kept free from the ground, but the very moment the animal raised his head in the air, at once the hook was thrown into the ground and he was prevented from taking another step forward. Now, dear readers, you may or may not know that when a cleft-hoofed animal starts to ascend a steep bank, unlike a solid-hoofed beast, he throws his head into the air instead of lowering it, and therefore it struck me at once that the purpose of this yoke was to keep the cattle from making their way up the sides of the mountain and getting lost.

But why should they want to clamber up the mountain sides? Simply because there was some kind of grass or herbage growing up there which was a delicacy to them, and knowing, as I well did, what risks animals will take and what fatigue they will undergo to reach a favorite grazing-ground, it struck me at once that if I would make it possible for them to reach this favorite food of theirs, they would be very glad to give me a lift on my way.

No sooner said than done. I forthwith retraced my steps until I fell in with a group of these cattle; and it did not take me many minutes to loosen their yokes from their horns and tie the hooks up under their bodies so that their progress up hill would not be interfered with.

They were delighted to find themselves so unexpectedly freed from the hateful drawback which permitted them merely to view the coveted grazing-grounds from afar, and then having cut me a suitable goad, I again started up the mountain, driving my new friends leisurely on ahead of me.

Upon reaching the spot where the superstitious peasants had thrown the tackle to the ground, I proceeded to load it upon the back of the gentlest beast of the lot, and was soon on my way again.