CHAPTER 3

The Tenants Take Possession

"Our own house—think of it!" cried Bettie, turning the key. "Push, somebody; the door sticks. There! It's open."

"Ugh!" said Mabel, drawing back hastily. "It's awfully dark and stuffy in there. I guess I won't go in just yet—it smells so dead-ratty."

"It's been shut up so long," explained Jean. "Wait. I'll pull some of the vines back from this window. There! Can you see better?"

"Lots," said Bettie. "This is the parlor, girls—but, oh, what raggedy paper. We'll need lots of pictures to cover all the holes and spots."

"We'd better clean it all first," advised sensible Jean. "The windows are covered with dust and the floor is just black."

"This," said Marjory, opening a door, "must be the dining-room. Oh! What a cunning little corner cupboard—just the place for our dishes."

"You mean it would be if we had any," said Mabel. "Mine are all smashed."

"Pooh!" said Jean. "We don't mean doll things—we want real, grown-up ones. Why, what a cunning little bedroom!"

"There's one off the parlor, too," said Marjory, "and it's even cunninger than this."

"My! what a horrid place!" exclaimed Mabel, poking an inquisitive nose into another unexplored room, and as hastily withdrawing that offended feature. "Mercy, I'm all over spider webs."

"That's the kitchen," explained Bettie. "Most of the plaster has fallen down and it's rained in a good deal. But here's a good stovepipe hole, and such a cunning cupboard built into the wall. What have you found, Jean?"

"Just a pantry," said Jean, holding up a pair of black hands, "and lots of dust. There isn't a clean spot in the house."

"So much the better," said Bettie, whose clouds always had a silver lining. "We'll have just that much more fun cleaning up. I'll tell you what let's do—and we've all day tomorrow to do it in. We'll just regularly clean house—I've always wanted to clean house."

"Me too," cried Mabel, enthusiastically. "We'll bring just oceans of water—"

"There's water here," interrupted Jean, turning a faucet. "Water and a pretty good sink. The water runs out all right."

"That's good," said Bettie. "We must each bring a broom, and soap—"

"And rags," suggested Jean.

"And papers for the shelves," added Marjory.

"And wear our oldest clothes," said Bettie.

"Oo-ow, wow!" squealed Mabel.

"What's the matter?" asked the girls, rushing into the pantry.

"Spiders and mice," said Mabel. "I just poked my head into the cupboard and a mouse jumped out. I'm all spider-webby again, too."

"Well, there won't be any spiders by tomorrow night," said Bettie, consolingly, "or any mice either, if somebody will bring a cat. Now let's go home to supper—I'm hungry as a bear."

"Everybody remember to wear her oldest clothes," admonished Jean, "and to bring a broom."

"I'll tie the key to a string and wear it around my neck night and day," said Bettie, locking the door carefully when the girls were outside. "Aren't we going to have a perfectly glorious summer?"

When Mr. Black, on the way to his office the next morning, met his four little friends, he did not recognize them. Jean, who was fourteen, and tall for her age, wore one of her mother's calico wrappers tied in at the waist by the strings of the cook's biggest apron. Marjory, in the much shrunken gown of a previous summer, had her golden curls tucked away under the housemaid's sweeping cap. Bettie appeared in her very oldest skirt surmounted by an exceedingly ragged jacket and cap discarded by one of her brothers; while Mabel, with her usual enthusiasm, looked like a veritable rag-bag. When Bettie had unlocked the door—she had slept all night with the key in her hand to make certain that it would not escape—the girls filed in.

"I know how to handle a broom as well as anybody," said Mabel, giving a mighty sweep and raising such a cloud of dust that the four housecleaners were obliged to flee out of doors to keep from strangling.

"Phew!" said Jean, when she had stopped coughing. "I guess we'll have to take it out with a shovel. The dust must be an inch thick."

"Wait," cried Marjory, darting off, "I'll get Aunty's sprinkling can; then the stuff won't fly so."

After that the sweeping certainly went better. Then came the dusting.

"It really looks very well," said Bettie, surveying the result with her head on one side and an air of housewifely wisdom that would have been more impressive if her nose hadn't been perfectly black with soot. "It certainly does look better, but I'm afraid you girls have most of the dust on your faces. I don't see how you managed to do it. Just look at Mabel."

"Just look at yourself!" retorted Mabel, indignantly. "You've got the dirtiest face I ever saw."

"Never mind," said Jean, gently. "I guess we're all about alike. I've wiped all the dust off the walls of this parlor. Now I'm going to wash the windows and the woodwork, and after that I'm going to scrub the floor."

"Do you know how to scrub?" asked Marjory.

"No, but I guess I can learn. There! Doesn't that pane look as if a really-truly housemaid had washed it?"

"Oh, Mabel! Do look out!" cried Marjory.

But the warning came too late. Mabel stepped on the slippery bar of soap and sat down hard in a pan of water, splashing it in every direction. For a moment Mabel looked decidedly cross, but when she got up and looked at the tin basin, she began to laugh.

"That's a funny way to empty a basin, isn't it?" she said. "There isn't a drop of water left in it."

"Well, don't try it again," said Jean. "That's Mrs. Tucker's basin and you've smashed it flat. You should learn to sit down less suddenly."

"And," said Marjory, "to be more careful in your choice of seats—we'll have to take up a collection and buy Mrs. Tucker a new basin, or she'll be afraid to lend us anything more."

The girls ran home at noon for a hasty luncheon. Rested and refreshed, they all returned promptly to their housecleaning.

Nobody wanted to brush out the kitchen cupboard. It was not only dusty, but full of spider webs, and worst of all, the spiders themselves seemed very much at home. The girls left the back door open, hoping that the spiders would run out of their own accord. Apparently, however, the spiders felt no need of fresh air. Bettie, without a word to anyone, ran home, returning a moment later with her brother Bob's old tame crow blinking solemnly from her shoulder. She placed the great, black bird on the cupboard shelf and in a very few moments every spider had vanished down his greedy throat.

"He just loves them," said Bettie.

"How funny!" said Mabel. "Who ever heard of getting a crow to help clean house? I wish he could scrub floors as well as he clears out cupboards."

The scrubbing, indeed, looked anything but an inviting task. Jean succeeded fairly well with the parlor floor, though she declared when that was finished that her wrists were so tired that she couldn't hold the scrubbing-brush another moment. Marjory and Bettie together scrubbed the floor of the tiny dining-room. Mabel made a brilliant success of one of the little bedrooms, but only, the other girls said, by accidentally tipping over a pail of clean water upon it, thereby rinsing off a thick layer of soap. Then Jean, having rested for a little while, finished the remaining bedroom and Marjory scoured the pantry shelves.

The kitchen floor was rough and very dirty. Nobody wanted the task of scrubbing it. The tired girls leaned against the wall and looked at the floor and then at one another.

"Let's leave it until Monday," said Mabel, who looked very much as if the others had scrubbed the floor with her. "I've had all the housecleaning I want for one day."

"Oh, no," pleaded Bettie. "Everything else is done. Just think how lovely it would be to go home tonight with all the disagreeable part finished! We could begin to move in Monday if we only had the house all clean."

"Couldn't we cover the dirtiest places with pieces of old carpet?" demanded Mabel.

"Oh, what dreadful housekeeping that would be!" said Marjory.

"Yes," said Jean, "we must have every bit of it nice. Perhaps if we sit on the doorstep and rest for a few moments we'll feel more like scrubbing."

The tired girls sat in a row on the edge of the low porch. They were all rather glad that the next day would be Sunday, for between the dandelions and the dust they had had a very busy week.

"Why!" said Bettie, suddenly brightening. "We're going to have a visitor, I do believe."

"Hi there!" said Mr. Black, turning in at the gate. "I smell soap. Housecleaning all done?"

"All," said Bettie, wearily, "except the kitchen floor, and, oh! we're so tired. I'm afraid we'll have to leave it until Monday, but we just hate to."

"Too tired to eat peanuts?" asked Mr. Black, handing Bettie a huge paper bag. "Stay right here on the doorstep, all of you, and eat every one of these nuts. I'll look around and see what you've been doing—I'm sure there can't be much dirt left inside when there's so much on your faces."

It seemed a pity that Mr. Black, who liked little girls so well, should have no children of his own. A great many years before Bettie's people had moved to Lakeville, he had had one sister; and at another almost equally remote period he had possessed one little daughter, a slender, narrow-chested little maid, with great, pathetic brown eyes, so like Bettie's that Mr. Black was startled when Dr. Tucker's little daughter had first smiled at him from the Tucker doorway, for the senior warden's little girl had lived to be only six years old. This, of course, was the secret of Mr. Black's affection for Bettie.

Mr. Black, who was a moderately stout, gray-haired man of fifty-five, with kind, dark eyes and a strong, rugged, smooth-shaven countenance, had a great deal of money, a beautiful home perched on the brow of a green hill overlooking the lake, and a silk hat. This last made a great impression on the children, for silk hats were seldom worn in Lakeville. Mr. Black looked very nice indeed in his, when he wore it to church Sunday morning, but Bettie felt more at home with him when he sat bareheaded on the rectory porch, with his short, crisp, thick gray hair tossed by the south wind.

Besides these possessions, Mr. Black owned a garden on the sheltered hillside where wonderful roses grew as they would grow nowhere else in Lakeville. This was fortunate because Mr. Black loved roses, and spent much time poking about among them with trowel and pruning shears. Then, there were shelves upon shelves of books in the big, dingy library, which was the one room that the owner of the large house really lived in. A public-spirited man, Mr. Black had a wide circle of acquaintances and a few warm friends; but with all his possessions, and in spite of a jovial, cheerful manner in company, his dark, rather stern face, as Bettie had very quickly discovered, was sad when he sat alone in his pew in church. He had really nothing in the world to love but his books and his roses. It was evident, to anyone who had time to think about it, that kind Mr. Black, whose wife had died so many years before that only the oldest townspeople could remember that he had had a wife, was, in spite of his comfortable circumstances, a very lonely man, and that, as he grew older, he felt his loneliness more keenly. There were others besides Bettie who realized this, but it was not an easy matter to offer sympathy to Mr. Black—there was a dignity about him that repelled anything that looked like pity. Bettie was the one person who succeeded, without giving offense, in doing this difficult thing, but Bettie did it unconsciously, without in the least knowing that she had accomplished it, and this, of course, was another reason for the strong friendship between Mr. Black and her.

The girls found the peanuts decidedly refreshing; their unusual exercise had given them astonishing appetites.

"I wonder," said Bettie, some ten minutes later, when the paper bag was almost empty, "what Mr. Black is doing in there."

"I think, from the swishing, swushing sounds I hear," said Jean, "that Mr. Black must be scrubbing the kitchen."

"What!" gasped the girls.

"Come and see," said Jean, stealing in on tiptoe.

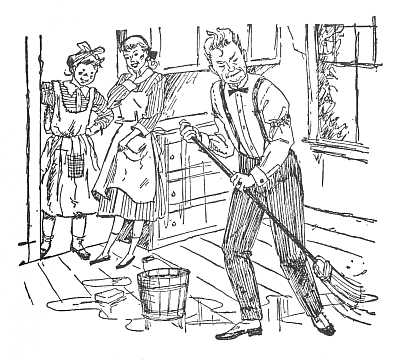

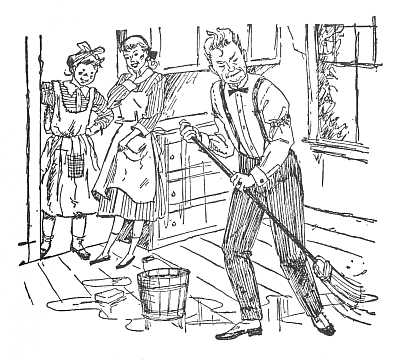

There, sure enough, was stout Mr. Black dipping a broom every now and then into a pail of soapy water and vigorously sweeping the floor with it.

"I think," whispered Mabel, ruefully, "that that's Mother's best broom."

"Never mind," consoled Jean. "You can take mine home if you think she'll care. It's really mine because I bought it when we had that broom drill in the sixth grade. It's been hanging on my wall ever since."

"Hi there!" exclaimed Mr. Black, who, looking up suddenly, had discovered the smiling girls in the doorway. "You didn't know I could scrub, did you?"

Mr. Black, quite regardless of his spotless cuffs and his polished shoes, drew a bucket of fresh water and dashed it over the floor, sweeping the flood out of doors and down the back steps.

"There," said Mr. Black, standing the broom in the corner, "if there's a cleaner house in town than this, I don't know where you'll find it. In return for scrubbing this kitchen, of course, I shall expect you to invite me to dinner when you get to housekeeping."

"We will! We do!" shouted the girls. "And we'll cook every single thing ourselves."

"I don't know that I'll insist on that," returned Mr. Black, teasingly, "but I shan't let you forget about the dinner."