CHAPTER 12

A Lively Afternoon

It happened one day that Mrs. Milligan was obliged to spend a long afternoon at the dentist's, leaving Laura in charge of the house. Unfortunately it happened, too, that this was the day when the sewing society met, and Mrs. Tucker had asked Bettie to stay home for the afternoon because the next-to-the-youngest baby was ill with a croupy cold and could not go out of doors to the cottage. Devoted Jean offered to stay with her beloved Bettie, who gladly accepted the offer. Before going to Bettie's, however, Jean ran over to Dandelion Cottage to tell the other girls about it.

"Mabel," asked Jean, a little doubtfully, "are you quite sure you'll be able to turn a deaf ear if Laura should happen to bother you? I'm half afraid to leave you two girls here alone."

"You needn't be," said Mabel. "I wouldn't associate with Laura if I were paid for it. She isn't my kind."

"No," said Marjory, "you needn't worry a mite. We're going to sit on the doorstep and read a perfectly lovely book that Aunty Jane found at the library—it's one that she liked when she was a little girl. We're going to take turns reading it aloud."

"Well, that certainly ought to keep you out of mischief. You'll be safe enough if you stick to your book. If anything should happen, just remember that I'm at Bettie's."

"Yes, Grandma," said Marjory, with a comical grimace.

Jean laughed, ran around the house, and squeezed through the hole in the back fence.

Half an hour later, lonely Laura, discovering the girls on their doorstep, amused herself by sicking the dog at them. Towser, however, merely growled lazily for a few moments and then went to sleep in the sunshine—he, at least, cherished no particular grudge against the girls and probably by that time he recognized them as neighbors.

Then Laura perched herself on one of the square posts of the dividing fence and began to sing—in her high, rasping, exasperating voice—a song that was almost too personal to be pleasant. It had taken Laura almost two hours to compose it, some days before, and fully another hour to commit it to memory, but she sang it now in an offhand, haphazard way that led the girls to suppose that she was making it up as she went along. It ran thus:

There's a lanky girl named Jean,

Who's altogether too lean.

Her mouth is too big,

And she wears a wig,

And her eyes are bright sea-green.

Of course it was quite impossible to read even a thrillingly interesting book with rude Laura making such a disturbance. If the girls had been wise, they would have gone into the house and closed the door, leaving Laura without an audience; but they were not wise and they were curious. They couldn't help waiting to hear what Laura was going to sing about the rest of them, and they did not need to wait long; Laura promptly obliged them with the second verse:

There's another named Marjory Vale,

Who's about the size of a snail.

Her teeth are light blue—

She hasn't but two—

And her hair is much too pale.

Laura had, in several instances, sacrificed truth for the sake of rhyme, but enough remained to injure the vanity of the subjects of her song very sharply. Marjory breathed quickly for a moment and flushed pink but gave no audible sign that she had heard. Laura, somewhat disappointed, proceeded:

There's a silly young lass called Bet,

Thinks she's ev'rybody's sweet pet.

She slapped my brother,

Fibbed to my mother—

I know what she's going to get.

Mabel snorted indignantly over this injustice to her beloved Bettie and started to rise, but Marjory promptly seized her skirt and dragged her down. Laura, however, saw the movement and was correspondingly elated. It showed in her voice:

But the worst of the lot is Mabel,

She eats all the pie she's able.

She's round as a ball,

Has no waist at all,

And her manners are bad at the table.

Marjory giggled. She had no thought of being disloyal, but this verse was certainly a close fit.

"You just let me go," muttered Mabel, crimson with resentment and struggling to break away from Marjory's restraining hand. "I'll push her off that post."

"Hush!" said diplomatic Marjory, "perhaps there's more to the song."

But there wasn't. Laura began at the beginning and sang all the verses again, giving particular emphasis to the ones concerning Mabel and Marjory. This, of course, grew decidedly monotonous; the girls got tired of the constant repetition of the silly song long before Laura did. There was something about the song, too, that caught and held their attention. Irresistibly attracted, held by an exasperating fascination, neither girl could help waiting for her own special verse. But while this was going on, Mabel, with a finger in the ear nearest Laura, was industriously scribbling something on a scrap of paper.

As everybody knows, the poetic muse doesn't always work when it is most needed, and Mabel was sadly handicapped at that moment. She was not satisfied with her hasty scrawl but, in the circumstances, it was the best she could do. Suddenly, before Marjory realized what was about to happen, Mabel was shouting back, to an air quite as objectionable as the one Laura was singing:

There's a very rude girl named Laura,

Whose ways fill all with horror.

She's all the things she says we are;

All know this to their sorrow.

"Yah! yah!" retorted quick-witted Laura. "There isn't a rhyme in your old song. If I couldn't rhyme better 'n that, I'd learn how. Come over and I'll teach you!"

For an instant, Mabel looked decidedly crushed—no poet likes his rhymes disparaged. Laura, noting Mabel's crestfallen attitude, went into gales of mocking laughter and when Mabel looked at Marjory for sympathy Marjory's face was wreathed in smiles. It was too much; Mabel hated to be laughed at.

"I can rhyme," cried Mabel, springing to her feet and giving vent to all her grievances at once. "My table manners are good. I'm not fat. I've got just as much waist as you have."

"You've got more," shrieked delighted Laura.

Faithless Marjory, struck by this indubitable truth, laughed outright.

"You—you can't make Indian-bead chains," sputtered Mabel, trying hard to find something crushing to say. "You can't make pancakes. You can't drive nails."

"Yah," retorted Laura, who was right in her element, "you can't throw straight."

"Neither can you."

"I can! If I could find anything to throw I'd prove it."

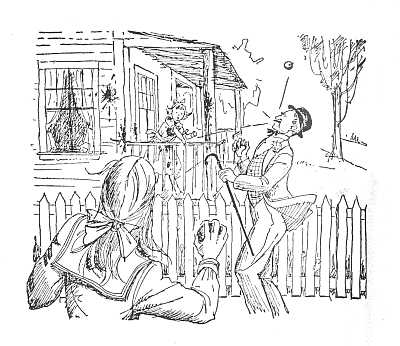

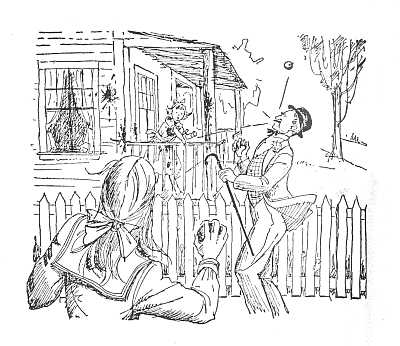

Just at this unfortunate moment, a grocery-man arrived at the Milligan house with a basketful of beautiful scarlet tomatoes. In another second, Laura, anxious to prove her ability, had jumped from the fence, seized the basket and, with unerring aim, was delightedly pelting her astonished enemy with the gorgeous fruit. Mabel caught one full in the chest, and as she turned to flee, another landed square in the middle of her light-blue gingham back; Marjory's shoulder stopped a third before the girls retreated to the house, leaving Laura, a picturesque figure on the high post, shouting derisively:

"Proved it, didn't I? Ki! I proved it."

Marjory, pleading that discretion was the better part of valor, begged Mabel to stay indoors; but Mabel, who had received, and undoubtedly deserved, the worst of the encounter, was for instant revenge. Rushing to the kitchen she seized the pan of hard little green apples that Grandma Pike had bequeathed the girls and flew with them to the porch.

Mabel's first shot took Laura by surprise and landed squarely between her shoulders. Mabel was surprised, too, because throwing straight was not one of her accomplishments. She hadn't hoped to do more than frighten her exasperating little neighbor.

Elated by this success, Mabel threw her second apple, which, alas, flew wide of its mark and caught poor unprepared Mr. Milligan, who was coming in at his own gate, just under the jaw, striking in such a fashion that it made the astonished man suddenly bite his tongue.

Nobody likes to bite his tongue. Naturally Mr. Milligan was indignant; indeed, he had every reason to be, for Mabel's conduct was disgraceful and the little apple was very hard. Entirely overlooking the fact that Laura, who had failed to notice her father's untimely arrival, was still vigorously pelting Mabel, who stood as if petrified on the cottage steps and was making no effort to dodge the flying scarlet fruit, Mr. Milligan shouted:

"Look here, you young imps, I'll see that you're turned out of that cottage for this outrage. We've stood just about enough abuse from you. I don't intend to put up with any more of it."

Then, suddenly discovering what Laura, who had turned around in dismay at the sound of her father's voice, was doing, angry Mr. Milligan dragged his suddenly crestfallen daughter from the fence, boxed her ears soundly, and carried what was left of the tomatoes into the house; for that particular basket of fruit had been sent from very far south and express charges had swelled the price of the unseasonable dainty to a very considerable sum.

Marjory, in the cottage kitchen, was alternately scolding and laughing at woebegone Mabel when Jean and Bettie, released from their charge, ran back to Dandelion Cottage. Mabel, crying with indignation, sat on the kitchen stove rubbing her eyes with a pair of grimy fists—Mabel's hands always gathered dust.

"Oh, Mabel! how could you!" groaned Jean, when Marjory had told the afternoon's story. "I'll never dare to leave you here again without some sensible person to look after you. Don't you see you've been almost—yes, quite—as bad as Laura?"

"I don't care," sobbed unrepentant Mabel. "If you'd heard those verses—and—and Marjory laughed at me."

"Couldn't help it," giggled Marjory, who was perched on the corner of the kitchen table.

"But surely," reproached gentle-mannered Jean, "it wasn't necessary to throw things."

"I guess," said Mabel, suddenly sitting up very straight and disclosing a puffy, tear-stained countenance that moved Marjory to fresh giggles, "if you'd felt those icy cold tomatoes go plump in your eye and every place on your very newest dress, you'd have been pretty mad, too. Look at me! I was too surprised to move after I'd hit Mr. Milligan—I never saw him coming at all—and I guess every tomato Laura threw hit me some place."

"Yes," confirmed Marjory, "I'll say that much for Laura. She can certainly throw straighter than any girl I ever knew—she throws just like a boy."

Jean, still worried and disapproving, could not help laughing, for Laura's plump target showed only too good evidence of Laura's skill. Mabel's new light-blue gingham showed a round scarlet spot where each juicy missile had landed; and besides this, there were wide muddy circles where her tears had left highwater marks about each eye.

"But, dear me," said Jean, growing sober again, "think how low-down and horrid it will sound when we tell about it at home. Suppose it should get into the papers! Apples and tomatoes! If boys had done it it would have sounded bad enough, but for girls to do such a thing! Oh, dear, I do wish I'd been here to stop it!"

"To stop the tomatoes, you mean," said Mabel. "You couldn't have stopped anything else, for I just had to do something or burst. I've felt all the week just like something sizzling in a bottle and waiting to have the cork pulled! I'll never be able to do my suffering in silence the way you and Bettie do. Oh, girls, I feel just loads better."

"Well, you may feel better," said irrepressible Marjory, "but you certainly look a lot worse. With those muddy rings on your face you look just like a little owl that isn't very wise."

"Oh, dear," mourned Bettie, "if Miss Blossom had only stayed we wouldn't have had all this trouble with those people."

"No," said Marjory, shrewdly, "Miss Blossom would probably have made Laura over into a very good imitation of an honest citizen. I don't think, though, that even Miss Blossom could make Laura anything more than an imitation, because—well, because she's Laura. It's different with Mabel—"

Mabel looked up expectantly, and Marjory, who was in a teasing mood, continued.

"Yes," said she, encouragingly, "Miss Blossom might have succeeded in making a nice, polite girl out of Mabel if she'd only had time—"

"How much time?" demanded Mabel, with sudden suspicion.

"Oh, about a thousand years," replied Marjory, skipping prudently behind tall Jean.

"Never mind, Mabel," said Bettie, who always sided with the oppressed, slipping a thin arm about Mabel's plump shoulders. "We like you pretty well, anyway, and you've certainly had an awful time."

"Do you think," asked Mabel, with sudden concern, "that Mr. Milligan could get us turned out of the cottage? You know he threatened to."

"No," said Bettie. "The cottage is church property and no one could do anything about it with Mr. Black away because he's the senior warden. Father said only this morning that there was all sorts of church business waiting for him."

"Well," said Mabel, with a sigh of relief, "Mr. Black wouldn't turn us out, so we're perfectly safe. Guess I'll go out on the porch and sing my Milligan song again."

"I guess you won't," said Jean. "There's a very good tub in the Bennett house and I'd advise you to go home and take a bath in it—you look as if you needed two baths and a shampoo. Besides, it's almost supper time."

Laura's version of the story, unfortunately, differed materially from the truth. There was no gainsaying the tomatoes—Mr. Milligan had seen those with his own eyes; but Laura claimed that she had been compelled to use those expensive vegetables as a means of self-defense. According to Laura, whose imagination was as well trained as her arm, she had been the innocent victim of all sorts of persecution at the hands of the four girls. They had called her a thief and had insulted not only her but all the other Milligans. Mabel, she declared, had opened hostilities that afternoon by throwing stones, and poor, abused Laura had only used the tomatoes as a last resort. The apple that struck Mr. Milligan was, she maintained, the very last of about four dozen.

Had the Milligans not been prejudiced, they might easily have learned how far from the truth this assertion was, for the porch of Dandelion Cottage was still bespattered with tomatoes, whereas in the Milligan yard there were no traces of the recent encounter. This, to be sure, was no particular credit to Mabel for there might have been had Mr. Milligan delayed his coming by a very few minutes, since Mabel's pan still contained seven hard little apples and Mabel still longed to use them.

The Milligans, however, were prejudiced. Although Laura was often rude and disagreeable at home, she was the only little girl the Milligans had; in any quarrel with outsiders they naturally sided with their own flesh and blood, and, in spite of the tomatoes, they did so now. In her mother Laura found a staunch champion.

"I won't have those stuck-up little imps there another week," said Mrs. Milligan. "If you don't see that they're turned out, James, I will."

"They stick out their tongues at me every time they see me," fibbed Laura, whose own tongue was the only one that had been used for sticking-out purposes. "They said Ma was no lady, and—"

"I'm going to complain of them this very night," said Mrs. Milligan, with quick resentment. "I'll show 'em whether I'm a lady or not."

"Who'll you complain to?" asked Laura, hopefully.

"The church warden, of course. These cottages both belong to the church."

"Mr. Black is the girls' best friend," said Laura. "He wouldn't believe anything against them—besides, he's away."

"Mr. Downing isn't," said Mr. Milligan. "I paid him the rent last week. We'll threaten to leave if he doesn't turn them out. He's a sharp businessman and he wouldn't lose the rent of this house for the sake of letting a lot of children use that cottage. I'll see him tomorrow."

"No," said Mrs. Milligan, "just leave the matter to me. I'll talk to Mr. Downing."

"Suit yourself," said Mr. Milligan, glad perhaps to shirk a disagreeable task.

After supper that evening, Mrs. Milligan put on her best hat and went to Mr. Downing's house, which was only about three blocks from her own. The evening was warm and she found Mr. and Mrs. Downing seated on their front porch. Mrs. Milligan accepted their invitation to take a chair and began at once to explain the reason for her visit.

The angry woman's tale lost nothing in the telling; indeed, it was not hard to discover how Laura came by her habit of exaggerating. When Mrs. Milligan went home half an hour later, Mr. Downing was convinced that the church property was in dangerous hands. He couldn't see what Mr. Black had been thinking of to allow careless, impudent children who played with matches, drove nails in the cottage plaster, and insulted innocent neighbors, to occupy Dandelion Cottage.

"Somehow," said Mrs. Downing, when the visitor had departed, "I don't like that woman. She isn't quite a lady."

"Nonsense, my dear," said Mr. Downing. "If only half the things she hints at are true, there would be reason enough for closing the cottage. The place itself doesn't amount to much, I've been told, but a fire started there would damage thousands of dollars' worth of property. Besides, there's the rent from the house those people are in—we don't want to lose that, you know."

"Still, there are always tenants—"

"Not at this time of the year. I'll look into the matter as soon as I can find time."

"Remember," said Mrs. Downing, thinking of Mrs. Milligan's rasping tones, "that there are two sides to every story."

"My dear," said Mr. Downing, complacently, "I shall listen with the strictest impartiality to both sides."