CHAPTER 17

Several Surprises Take Effect

Mr. Black opened the door of his hotel apartment in Washington one sultry noon in response to a vigorous, prolonged rapping from without. The bellboy handed him a telegram. When Mr. Black had read the long message he smiled and frowned, but cheerfully paid the three dollars and forty-one cents additional charges that the messenger demanded.

It was Mabel's message; the clerk had transmitted it faithfully, even to the two misspelled words that had proved too much for the excited little writer. If the receiving clerk had not considerately tucked in a few periods for the sake of clearness, there would have been no punctuation marks, because, as everybody knows, very few telegrams are punctuated; but Mabel, of course, had not taken that into consideration. It was quite the longest message and certainly the most amusing one that Mr. Black had ever received. It read:

"DEAR MR. BLACK,

"We are well but terribly unhappy for the worst has happened. Cant you come to the reskew as they say in books for we are really in great trouble because the Milligans a very unpolite and untruthful family next door want dandelion cottage for themselves the pigs and Mr. Downing says we must move out at once and return the key our own darling key that you gave us. We are moving out now and crying so hard we can hardly write. I mean myself. Is Mr. Downing the boss of the whole church. Cant you tell him we truly paid the rent for all summer by digging dandelions. He does not believe us. We are too sad to write any more with love from your little friends

"JEAN MARJORY BETTIE AND I.

"P. S. How about your dinner party if we lose the cottage?"

Mr. Black read and reread the typewritten yellow sheet a great many times; sometimes he frowned, sometimes he chuckled; the postscript seemed to please him particularly, for whenever he reached that point his deep-set eyes twinkled merrily. Presently he propped the dispatch against the wall at the back of his table and sat down in front of it to write a reply. He wrote several messages, some long, some short; then he tore them all up—they seemed inadequate compared with Mabel's.

"That man Downing," said he, dropping the scraps into the waste-basket, "means well, but he muddles every pie he puts his finger in. Probably if I wire him he'll botch things worse than ever. Dear me, it is too bad for those nice children to lose any part of their precious stay in that cottage, now, for of course they'll have to give it up when cold weather comes. If I can wind my business up today there isn't any good reason why I can't go straight through without stopping in Chicago. It's time I was home, anyway; it's pretty warm here for a man that likes a cold climate."

Meanwhile, things were happening in Mr. Black's own town.

It was a dark, threatening day when the Milligans, delighted at the success of their efforts to dislodge its rightful tenants, hurriedly moved into Dandelion Cottage; but, dark though it was, Mrs. Milligan soon began to find her new possession full of unsuspected blemishes. Now that the pictures were down and the rugs were up, she discovered the badly broken plaster, the tattered condition of the wall paper, the leaking drain, and the clumsily mended rat-holes. She found, too, that she had made a grievous mistake in her calculations. She had supposed that the tiny pantry was a third bedroom; with its neat muslin curtains, it certainly looked like one when viewed from the outside; and crafty Laura, intensely desirous of seeing the enemy ousted from the cottage at any price, had not considered it necessary to enlighten her mother.

"My goodness!" exclaimed Mrs. Milligan, a thin woman with a shrewish countenance now much streaked with dust. "I thought you said there was a fine cellar under this house? It's barely three feet deep, and there's no stairs and no floor. It's full of old rubbish."

"I never was down there," admitted Laura, dropping a dishpanful of cooking utensils with a crash and hastily making for safe quarters behind a mountain of Milligan furniture, "but I've often seen the trap door."

"It hasn't been opened for years. And where's the nice big closet you said opened off the bedroom? There isn't a decent closet in this house. I don't see what possessed you—"

"It serves you right," said Mr. Milligan, unsympathetically. "You wouldn't wait for anything, but had to rush right in. I told you you'd better take your time about it, but no—"

"You know very well, James Milligan," snapped the irate lady, "that the Knapps wouldn't have taken our house if they couldn't have had it at once."

"Well, I don't know," growled Mr. Milligan, scowling crossly at the constantly growing heaps of incongruously mixed household goods, "where in Sam Hill you're going to put all that stuff. There isn't room for a cat to turn around, and the place ain't fit to live in, anyway."

Bad as things looked, even Mr. Milligan did not guess that first busy day how hopelessly out of repair the cottage really was; but he was soon to find out.

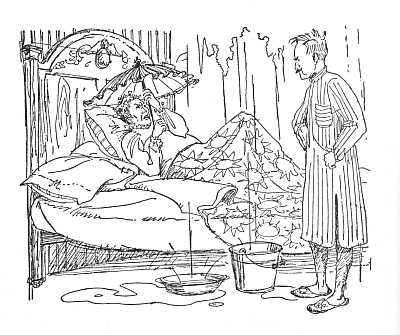

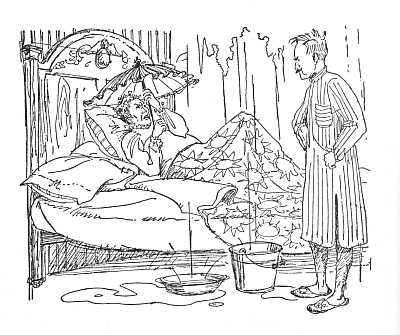

The summer had been an unusually dry one; so dry that the girls had been obliged to carry many pails of water to their garden every evening. The moving-day had been cloudy—out of sympathy, perhaps, for the little cottagers. That night it rained, the first long, steady downpour in weeks. This proved no gentle shower, but a fierce, robust, pelting flood. Seemingly a discriminating rain, too, choosing carefully between the just and the unjust, for most of it fell upon the Milligans. With the sole exception of the dining-room, every room in the house leaked like a sieve.

The tired, disgusted Milligans, drenched in their beds, leaped hastily from their shower baths to look about, by candlelight, for shelter. Mr. Milligan spread a mattress, driest side up, on the dining-room floor, and the unfortunate family spent the rest of the night huddled in an uncomfortable heap in the one dry spot the house afforded.

Very early the next morning they sent post-haste for Mr. Downing.

Mr. Downing, who hated to be disturbed before eight, arrived at ten o'clock; and, with an expert carpenter, made a thorough examination of the house, which the rain had certainly not improved.

"It will take three hundred—possibly four hundred dollars," said the carpenter, who had been making a great many figures in a worn little note-book, "to make this place habitable. It needs a new roof, new chimneys, new floors, a new foundation, new plumbing, new plaster—in short, just about everything except the four outside walls. Then there are no lights and no heating plant, which of course would be extra. It's probably one of the oldest houses in town. What's it renting for?"

"Ten dollars a month."

"It isn't worth it. Half that money would be a high price. Even if it were placed in good repair it would be six years at least before you could expect to get the money expended on repairs back in rent. The only thing to do is to tear it down and build a larger and more modern house that will bring a better rent, for there's no money in a ten-dollar house on a lot of this size—the taxes eat all the profits."

"Well," said Mr. Downing, "this house certainly looked far more comfortable when I saw it the other day than it does now. Those children must have had the defects very well concealed. They deceived me completely."

"They deceived us all," said Mrs. Milligan, resentfully. "Half of our furniture is ruined. Look at that sofa!"

Mr. Downing looked. The drenched old-gold plush sofa certainly looked very much like a half-drowned Jersey calf.

"Of course," continued Mrs. Milligan, sharply, "we expect to have our losses made good. Then we've had all our trouble for nothing, too. Of course we can't stay here—the place isn't fit for pigs. I suppose the best thing we can do is to move right back into our own house."

"Ye-es," said Mr. Milligan, overlooking the fact that Mrs. Milligan had inadvertently called her family pigs, "it certainly looks like the best thing to do. I'll go and tell the Knapps that they'll have to move out at once—we can't spend another night under this roof."

The Knapps, however, proved disobliging and flatly declined to move a second time. The Milligans had begged them to take the house off their hands, and they had signed a contract. Moreover, it was just the kind of house the Knapps had long been looking for, and now that they were moved, more than half settled, and altogether satisfied with their part of the bargain, they politely but firmly announced their intention of staying where they were until the lease should expire.

There was nothing the former tenants could do about it. They were homeless and quite as helpless as the four little girls had been in similar circumstances; and they made a far greater fuss about it. By this they gained, however, nothing but the disapproval of everybody concerned; so, finally, the Milligans, disgusted with Dandelion Cottage, with Mr. Downing, and for once even a little bit with themselves, dejectedly hunted up a new home in a far less pleasant neighborhood, and moved hurriedly out of Dandelion Cottage—and, except for the memories they left behind them, out of the story.