Chapter 3.XXXVII.—How Pantagruel persuaded Panurge to take counsel of a fool.

When Pantagruel had withdrawn himself, he, by a little sloping window in one of the galleries, perceived Panurge in a lobby not far from thence, walking alone, with the gesture, carriage, and garb of a fond dotard, raving, wagging, and shaking his hands, dandling, lolling, and nodding with his head, like a cow bellowing for her calf; and, having then called him nearer, spoke unto him thus: You are at this present, as I think, not unlike to a mouse entangled in a snare, who the more that she goeth about to rid and unwind herself out of the gin wherein she is caught, by endeavouring to clear and deliver her feet from the pitch whereto they stick, the foulier she is bewrayed with it, and the more strongly pestered therein. Even so is it with you. For the more that you labour, strive, and enforce yourself to disencumber and extricate your thoughts out of the implicating involutions and fetterings of the grievous and lamentable gins and springs of anguish and perplexity, the greater difficulty there is in the relieving of you, and you remain faster bound than ever. Nor do I know for the removal of this inconveniency any remedy but one.

Take heed, I have often heard it said in a vulgar proverb, The wise may be instructed by a fool. Seeing the answers and responses of sage and judicious men have in no manner of way satisfied you, take advice of some fool, and possibly by so doing you may come to get that counsel which will be agreeable to your own heart's desire and contentment. You know how by the advice and counsel and prediction of fools, many kings, princes, states, and commonwealths have been preserved, several battles gained, and divers doubts of a most perplexed intricacy resolved. I am not so diffident of your memory as to hold it needful to refresh it with a quotation of examples, nor do I so far undervalue your judgment but that I think it will acquiesce in the reason of this my subsequent discourse. As he who narrowly takes heed to what concerns the dexterous management of his private affairs, domestic businesses, and those adoes which are confined within the strait-laced compass of one family, who is attentive, vigilant, and active in the economic rule of his own house, whose frugal spirit never strays from home, who loseth no occasion whereby he may purchase to himself more riches, and build up new heaps of treasure on his former wealth, and who knows warily how to prevent the inconveniences of poverty, is called a worldly wise man, though perhaps in the second judgment of the intelligences which are above he be esteemed a fool,—so, on the contrary, is he most like, even in the thoughts of all celestial spirits, to be not only sage, but to presage events to come by divine inspiration, who laying quite aside those cares which are conducible to his body or his fortunes, and, as it were, departing from himself, rids all his senses of terrene affections, and clears his fancies of those plodding studies which harbour in the minds of thriving men. All which neglects of sublunary things are vulgarily imputed folly. After this manner, the son of Picus, King of the Latins, the great soothsayer Faunus, was called Fatuus by the witless rabble of the common people. The like we daily see practised amongst the comic players, whose dramatic roles, in distribution of the personages, appoint the acting of the fool to him who is the wisest of the troop. In approbation also of this fashion the mathematicians allow the very same horoscope to princes and to sots. Whereof a right pregnant instance by them is given in the nativities of Aeneas and Choroebus; the latter of which two is by Euphorion said to have been a fool, and yet had with the former the same aspects and heavenly genethliac influences.

I shall not, I suppose, swerve much from the purpose in hand, if I relate unto you what John Andrew said upon the return of a papal writ, which was directed to the mayor and burgesses of Rochelle, and after him by Panorme, upon the same pontifical canon; Barbatias on the Pandects, and recently by Jason in his Councils, concerning Seyny John, the noted fool of Paris, and Caillet's fore great-grandfather. The case is this.

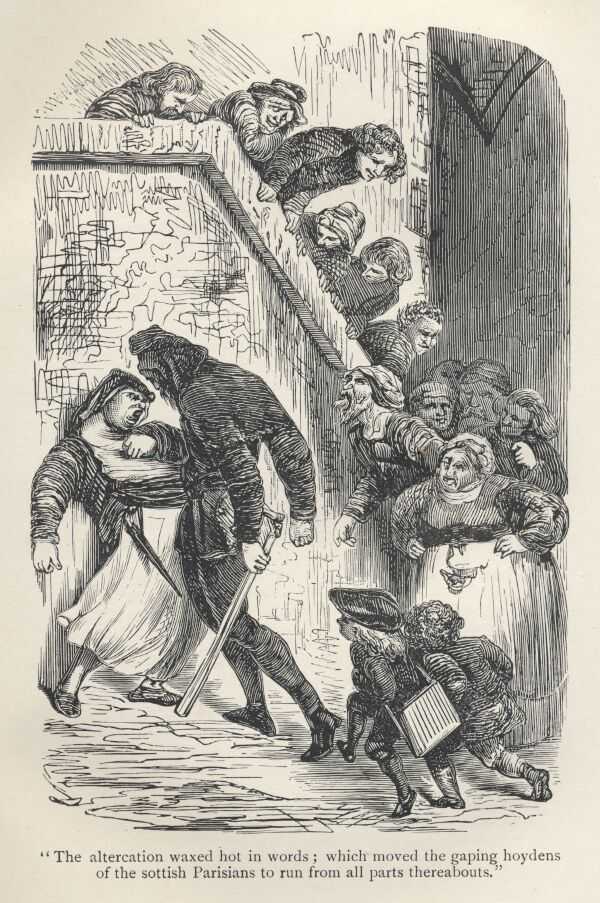

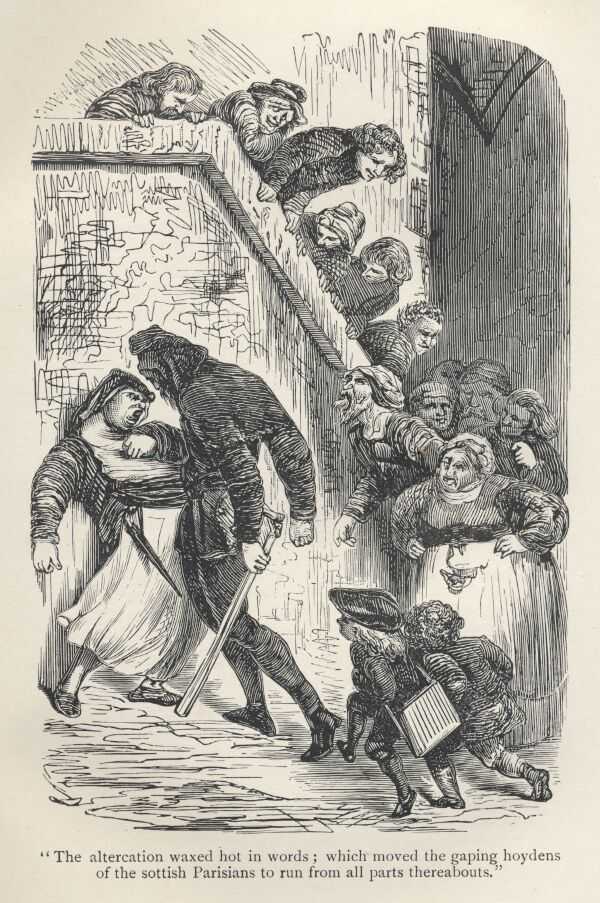

At Paris, in the roastmeat cookery of the Petit Chastelet, before the cookshop of one of the roastmeat sellers of that lane, a certain hungry porter was eating his bread, after he had by parcels kept it a while above the reek and steam of a fat goose on the spit, turning at a great fire, and found it, so besmoked with the vapour, to be savoury; which the cook observing, took no notice, till after having ravined his penny loaf, whereof no morsel had been unsmokified, he was about decamping and going away. But, by your leave, as the fellow thought to have departed thence shot-free, the master-cook laid hold upon him by the gorget, and demanded payment for the smoke of his roast meat. The porter answered, that he had sustained no loss at all; that by what he had done there was no diminution made of the flesh; that he had taken nothing of his, and that therefore he was not indebted to him in anything. As for the smoke in question, that, although he had not been there, it would howsoever have been evaporated; besides, that before that time it had never been seen nor heard that roastmeat smoke was sold upon the streets of Paris. The cook hereto replied, that he was not obliged nor any way bound to feed and nourish for nought a porter whom he had never seen before with the smoke of his roast meat, and thereupon swore that if he would not forthwith content and satisfy him with present payment for the repast which he had thereby got, that he would take his crooked staves from off his back; which, instead of having loads thereafter laid upon them, should serve for fuel to his kitchen fires. Whilst he was going about so to do, and to have pulled them to him by one of the bottom rungs which he had caught in his hand, the sturdy porter got out of his grip, drew forth the knotty cudgel, and stood to his own defence. The altercation waxed hot in words, which moved the gaping hoidens of the sottish Parisians to run from all parts thereabouts, to see what the issue would be of that babbling strife and contention. In the interim of this dispute, to very good purpose Seyny John, the fool and citizen of Paris, happened to be there, whom the cook perceiving, said to the porter, Wilt thou refer and submit unto the noble Seyny John the decision of the difference and controversy which is betwixt us? Yes, by the blood of a goose, answered the porter, I am content. Seyny John the fool, finding that the cook and porter had compromised the determination of their variance and debate to the discretion of his award and arbitrament, after that the reasons on either side whereupon was grounded the mutual fierceness of their brawling jar had been to the full displayed and laid open before him, commanded the porter to draw out of the fob of his belt a piece of money, if he had it. Whereupon the porter immediately without delay, in reverence to the authority of such a judicious umpire, put the tenth part of a silver Philip into his hand. This little Philip Seyny John took; then set it on his left shoulder, to try by feeling if it was of a sufficient weight. After that, laying it on the palm of his hand, he made it ring and tingle, to understand by the ear if it was of a good alloy in the metal whereof it was composed. Thereafter he put it to the ball or apple of his left eye, to explore by the sight if it was well stamped and marked; all which being done, in a profound silence of the whole doltish people who were there spectators of this pageantry, to the great hope of the cook's and despair of the porter's prevalency in the suit that was in agitation, he finally caused the porter to make it sound several times upon the stall of the cook's shop. Then with a presidential majesty holding his bauble sceptre-like in his hand, muffling his head with a hood of marten skins, each side whereof had the resemblance of an ape's face sprucified up with ears of pasted paper, and having about his neck a bucked ruff, raised, furrowed, and ridged with pointing sticks of the shape and fashion of small organ pipes, he first with all the force of his lungs coughed two or three times, and then with an audible voice pronounced this following sentence: The court declareth that the porter who ate his bread at the smoke of the roast, hath civilly paid the cook with the sound of his money. And the said court ordaineth that everyone return to his own home, and attend his proper business, without cost and charges, and for a cause. This verdict, award, and arbitrament of the Parisian fool did appear so equitable, yea, so admirable to the aforesaid doctors, that they very much doubted if the matter had been brought before the sessions for justice of the said place, or that the judges of the Rota at Rome had been umpires therein, or yet that the Areopagites themselves had been the deciders thereof, if by any one part, or all of them together, it had been so judicially sententiated and awarded. Therefore advise, if you will be counselled by a fool.