CHAPTER XVIII—A STRING OF BLUE BEADS

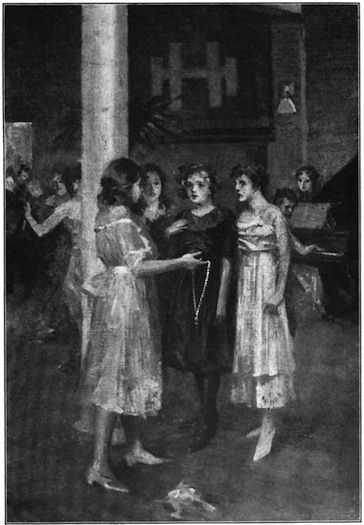

That very night, during the dancing hour, Marjory Vale was one of a group of girls clustered about Henrietta, who was demonstrating a new dance, that later became exceedingly popular.

Marjory, in the middle of the floor, was plainly visible when she pulled her handkerchief from her pocket. Something came with it—a long string of dull blue beads. The metal clasp had been caught in the hemstitching of the handkerchief but now came loose, allowing the heavy beads to land noisily on the hardwood floor. Marjory gazed at them for a long moment.

“For goodness’ sakes!” gasped Marjory, genuinely surprised. “How did I do that?”

“My beads!” shrieked Hazel, springing from her chair and pouncing on the necklace. “Marjory Vale! You took those beads out of my drawer.”

“My beads!” shrieked Hazel, pouncing on the necklace

“I never did,” said astonished Marjory, turning crimson and looking the very picture of guilt. “I noticed those beads on your neck the night of the ice cream festival—I haven’t seen them from that moment to this. I don’t know how they got in my pocket. Just before dinner time I rushed up and got into this dress—I always dance in this one, you know, and had laid it out on my bed before I went to walk. We were late getting back and I had to hurry into my clothes. And this is the first time I’ve taken my handkerchief out tonight.”

“I suppose it is your handkerchief,” said Hazel, rather unpleasantly.

“Why, no,” said Marjory, “it isn’t. It has Dorothy Miller’s name on it.”

“Then you couldn’t have gotten it by accident,” said Hazel. “The North Corridor washing comes up on a different day from yours.”

“I don’t know how I got it,” said Marjory, two large tears rolling down her cheeks. “But I—I think you’re just mean to me, Hazel. And I liked you.”

“Come and sit down,” said Sallie, slipping an arm about Marjory. “I know just how you feel.”

A curious thing had happened just after those heavy beads crashed to the floor. The older Mrs. Rhodes, seated near the wall to watch the dancing, turned her glittering black eyes toward Mrs. Henry Rhodes and the two women exchanged a most peculiar look. Then, with one accord, they rose and left the room.

Five minutes later, Mrs. Henry had taken a curious bundle from the very back corner of Marjory’s bureau drawer. She placed it on the bed and the two women proceeded to untie a large handkerchief, such as most of the girls wore with their middies.

The bundle contained two of the purses lost on the night of the concert but they were now empty, a ring that Mrs. Rhodes herself had lost, a wrist watch belonging to one of the Seniors, a number of handkerchiefs marked with other girls’ names, a silk sweater that belonged unmistakably to Augusta and various other small but incriminating objects. Nearly everything still bore its former owner’s name.

“So it’s Marjory Vale!” said Mrs. Rhodes.

“It looks that way,” said Mrs. Henry, “but—”

“Tell Doctor Rhodes to come right up here,” ordered the older woman. “Then you tell the Vale girl that she’s wanted in her room.”

Marjory found the Rhodes family standing beside her bed and pointing accusingly at the opened bundle.

“What have you to say to this?” demanded Doctor Rhodes.

“What is it?” asked Marjory.

“Don’t try to brazen it out,” said Mrs. Rhodes, in her most terrible manner. “You know very well what it is. We found this bundle in your bureau drawer hidden under your clothes. Whose sweater is this?”

“It looks very much like Augusta’s,” returned Marjory.

“Whose watch is that?”

“I don’t know. It isn’t mine.”

“Is this your ring?”

“Not any of those things are mine. Those handkerchiefs seem to be Miss Wilson’s. There’s a name on them.”

“Where is the money that was in these pocketbooks? Mrs. Bryan lost seven dollars and Mrs. Brown lost five—their cards are still in their purses.”

“I’m sure I don’t know. I’ve had my thirty cents a week and that’s all. If you really found those things in my drawer, somebody else must have put them there. I didn’t.”

The Rhodes family didn’t know exactly what to think. Marjory was sometimes thoughtlessly just a little bit impertinent, sometimes inclined to giggle when the occasion demanded sobriety, sometimes fidgety when quietness would have seemed more fitting; but Mrs. Henry Rhodes who, of the three, knew her best, had never known her to attempt to lie. If anything, indeed, she could recall times when Marjory had seemed almost too truthful.

“I think,” said Mrs. Henry, with a kind hand on Marjory’s shoulder, “we had better let this matter rest a little until something else comes up. There is something very queer about it. That pocketbook in Sallie’s room and now this. And everything so clearly marked.”

“But I don’t want this matter to rest,” protested Marjory. “I want it cleared up right away tonight. My goodness! This is just awful. I do love those beads of Hazel’s; but I didn’t take them. And, oh dear! There are girls that are going to believe I did unless you clear things up at once. I don’t want folks to think things like that about me.”

“Of course we’ll do what we can,” assured Mrs. Henry, “but it may take a little time. You must be patient for a little while, even if you have to rest under a suspicion that you don’t deserve. Shall I take these things away?”

“Please do.”

“And you know nothing at all about them?” asked the older Mrs. Rhodes. “You’re not keeping them for Sallie Dickinson?”

“For Sallie? Oh, no. Sallie wouldn’t have taken them—I’m sure of that.”

“What about your roommate?”

“Henrietta? Why! Henrietta wouldn’t either.”

“Don’t worry too much,” advised Mrs. Henry. “You’d better go to bed and forget your troubles for tonight.”

When Henrietta went to her room almost an hour later, she found poor little Marjory huddled in a small heap on her cot, weeping bitterly. Between sobs she told Henrietta what had happened.

“Cheer up,” said Henrietta, kissing Marjory’s hot ear because that was the only dry spot in sight. “We wanted to come sooner but we didn’t dare; you know it’s against the rules to go to our rooms during a social evening; but Jean is going to slip in after ‘Lights Out’ and cuddle you a little. That’s a good deal for Jean to do, you know, when she always behaves as well as she can. And it isn’t as bad as you think. I believe in you—that’s one. The rest of the Lakeville girls believe in you—that’s four more. You believe in yourself, that’s six. Sallie and little Jane Pool adore you, Maude swears by you and there are others—”

“It’s the others that worry me,” sighed Marjory. “They’re going to be just beastly to me, I know.”

Marjory was right. If several of the girls were not “Just beastly” they were pretty close to it. One of Hazel’s beads had been broken and that fact made Hazel more unforgiving than she might have been. Before long, too, the story of the black bundle found in the little girl’s room leaked out (no one knew just how), and many were the scornful glances cast at poor Marjory. If she had been unpopular before, she was considerably worse than unpopular now. She seemed to shrink visibly under the scathing looks of her schoolmates. She even began, it was noticed, to wear a guilty look that proved exasperating to Henrietta.

“Hold your head up,” Henrietta would say, vigorously shaking her little friend. “You haven’t a thing to be ashamed of. For mercy’s sake, look folks right in the eye as you used to. You’re not half as bad as you look. You’re a good child. Well, then, look like a good child.”

“I can’t help wondering,” confessed poor Marjory, “if I took those things in my sleep. Those blue beads—I just loved them.”

“And that horrible magenta sweater of Augusta’s—I suppose you loved that too.”

“Well, of course, I’d have to be asleep to take that. But do you think I could have taken those things in my sleep?”

“Of course you didn’t, Marjory. You didn’t take them at all. It was some kind of an accident. I’ve thought sometimes that poor old Abbie wasn’t quite right. You know how absent minded she is. I don’t think she’d steal anything; but she goes around in sort of a daze and her hands keep plucking at things, as if her mind were in one room and her body in another, like the time she set the dining room clock back and then accused everybody else of doing it. She’s always doing things like that. And you know she’s always had to do such a lot of picking up after years and years of careless girls—well, perhaps she’s gotten the habit of picking up things unconsciously and putting them in places where they don’t belong.”

“Well, anyway,” pleaded Marjory, “do watch me. If you catch me taking things in my sleep I hope you’ll be able to prove that I am asleep. And let’s all of us keep an eye on poor old Abbie daytimes. You might be right about her.”

“A letter for Miss Henrietta Bedford,” said Sallie’s voice at the door. “Charles was late again today. Hope it’s a nice one, Henrietta.”

Henrietta ripped her letter open hastily and read it.

“It isn’t a nice one. It’s from my grandmother. That London man that looks after Father’s affairs has started for China to hunt for him. Mr. Henshaw thinks he went to Shanghai but isn’t sure. You see, girls, there really is cause for alarm. I’d like to go right over there and help search for him; but of course I couldn’t. And it’s awfully hard to have nothing to do but wait.”