CHAPTER XXIII—PIG OR PORK?

The spring did perfectly wonderful things to the land adjacent to Highland Hall. It was really time that something was happening to improve that rather cheerless prospect. During the fall and winter months, the landscape had been mostly brown and gray and black, often more or less disfigured with patches of dingy snow; and a general misty bleakness surrounded the big, rather ugly building. But, with the coming of spring all this was changed. One could now see why the school prospectus had stated that Highland Hall was “beautifully located.”

The building stood at the top of a broad knoll. The level portion of this was covered by a well kept lawn—tall, lanky Charles, with his sandy hair on end and his angular elbows greatly in evidence, might be seen galloping over it with his lawn roller, getting certain bare spots ready for seed. The sloping banks were grassed also but this grass grew at its own sweet will; and then, quite suddenly it wasn’t grass but long stemmed violets. You could gather tremendous bunches of them and still there were millions left—popular Miss Blossom was fairly besieged with bouquets. Then, farther down the hillside were great patches of snowy bloodroot and miniature groves of mandrake with their hidden, creamy, heavily perfumed cups. There were wild crab-apple trees wreathed with wonderful pink and white buds and blossoms. The edges of the unsightly ditches along the road suddenly became brilliantly green and pink with oxalis and there were sheltered nooks along the margin of the grove that were blue with mertensia or purple with the spider lily. Even the dry prairie was bursting forth with bloom; the lovely lavender of the bird’s foot violet and later the showy blossoms of the shooting star. There were gorgeous blue jays and orioles in the trees and meek gray doves in the hedges.

All the girls except Henrietta seemed bubbling over with happiness these days. Even Sallie, dreadfully shabby as to clothes and growing shabbier, was more cheerful, because she loved the spring season at Highland Park; and because she had never before possessed so many warm friends among the pupils. But Henrietta was visibly drooping. Her eyes wore a strained, anxious look and every day at mail time, her brilliant color deserted her, leaving her pale and trembling and quite unlike her usual vivacious self. At sight of a telegram arriving for Doctor Rhodes—and he often received as many as four a week—Henrietta’s lips would turn absolutely white. And several times, on the days when her grandmother’s letters came with no news of her still missing father, the girls had found her weeping. It was decidedly unlike Henrietta to weep.

But even Henrietta loved the wild flowers. Sallie knew where to find the choicest blossoms and Doctor Rhodes, glad to have the girls spend their leisure hours outdoors, even if it did increase their appetites alarmingly, extended their bounds a good half mile toward the south so the girls could roam at will.

One beautiful day, when school was dismissed earlier than usual, Mabel asked permission to take her friends as far as the cottage that contained Charles’s interesting family.

“I’m awfully fond of children,” explained Mabel. “I get lonesome for them when I don’t have any. Several times I’ve given candy and little presents to Charles to take home to those cunning babies; but I’m just dying to see them again and some of the girls want to go, too.”

“I’ve no objection to your seeing them,” said Doctor Rhodes, with a friendly chuckle, “but you are strictly forbidden to accept any invitations to stay with that family and you are not to bring any of them home with you.”

“I won’t,” promised Mabel. “Thank you ever so much for letting us go.”

The long walk over the blossoming prairie was wonderful and the other delighted youngsters thanked Mabel for planning the trip. The children at the cottage proved interesting and sweet and the girls loved them. Tommy remembered Mabel and said: “Please stay wiz us, you is nicer than Lizzie,” which pleased Mabel very much indeed, though of course she didn’t stay. The shy twins soon became friendly and even the baby was smiling and responsive. Mrs. Charles had been making cookies and generously passed them around. Then Maude looked at her watch and said that it was time to start back.

The girls decided to go home by the road that wound along over the prairie and somewhat west of the more direct but pathless route they had taken to the cottage. It was longer but Sallie said that interesting things grew along the edges. Even Sallie, however, was surprised at one thing they discovered. Mabel, who was trudging sturdily along, a little ahead of the others—and of course she had a right to lead the procession since it was her party—suddenly stopped short.

“Mercy!” she gasped. “What’s that!”

“What’s what?” asked Sallie, crowding to the front. “Is it a new flower? Oh! Why, that looks like a little pig!”

“But ’way out here!” cried Maude. “It couldn’t walk so far and there are no farms along here.”

“But the farmers ’way south of here,” returned Sallie, “send them in to the packing houses or down to the trains along this road. Probably this one got spilled out of somebody’s wagon and the driver never missed him.”

“No doubt,” said little Jane Pool, “the other piggies squealed so hard that the poor man never heard the cries of distress from this one.”

“It’s so little and pink and clean,” said Bettie, admiringly.

“But so naked,” objected Marjory. “It really seems as if it ought to be wearing baby clothes—little woolly ones. I’m glad it’s a warm day.”

“See,” said Mabel, “it’s sucking my finger—I think it likes me.”

“It’s hungry,” said Sallie. “It seems too bad to leave it here to starve.”

“But we don’t want any pig,” objected Henrietta. “I don’t think I like pigs.”

“I’m sure I don’t,” said Maude. “Come on, girls, let’s climb up the ladder to that windmill over there and walk all around it on that ledge—I think it’s wide enough. We don’t want to be bothered with any pigs.”

But the lonesome little pig had no intention of being left behind. It trotted along at the girls’ heels and squealed piteously in its efforts to keep up.

“Poor little thing,” said Bettie, “it’s just starving.”

“And tired,” said Mabel. “Every minute or two it loses its footing and rolls right over. It thinks it belongs to us.”

“You’re afraid to pick it up and carry it,” teased Marjory.

“I’m not,” said Mabel. “I’m going to do it. The rest of you can climb all the windmills you want to, but I’m going to be kind to this pig.”

Whereupon kind Mabel picked up the pig and carried it. At first, however, the little animal squirmed and struggled so much that Mabel had all she could do to keep from dropping him.

“But what are you going to do with him?” queried Bettie.

“Oh, I’ll just slip around to the kitchen door—if I ever get that far—and ask Charles to take care of him.”

“Charles won’t be home,” said Sallie. “That’s the time of day he goes to the station to get the bread.”

“Then I’ll take him up to my room,” said Mabel, whose pet was now quite satisfied in her arms. “Perhaps you could bring up a cup of milk for him.”

“Mabel never comes home empty handed,” laughed Marjory. “And she isn’t particular what she brings, as long as it’s alive.”

“Won’t Isabelle be pleased?” laughed Maude.

“Lend him to me, Mabel. I’ll put him in Miss Woodruff’s bed.”

“No you won’t. I’m not going to have him abused.”

“Well, beware of Isabelle,” giggled Marjory.

Forewarned is forearmed. Mabel succeeded in slipping the pig into her bedroom closet without disturbing Isabelle who was busy writing what she was pleased to call “a poem.” She sent them, as she confided to Mabel, to her friend Clarence. Of course, when Isabelle had a pencil in her hand and that faraway look in her eye she was not likely to notice mere pigs.

Sallie had contrived a nursing bottle for the infant. Mabel, seated on the closet floor, succeeded in feeding her charge and presently made a nest for him by dumping the stockings out of her round mending basket; but to her surprise the pig, not being built that way, refused to curl. His tail curled beautifully but the rest of him wouldn’t. In no way, in fact, was he as accommodating an animal as a kitten or even a puppy.

“If he’d only just cuddle,” groaned Mabel, “he’d be so much more comfortable to live with.”

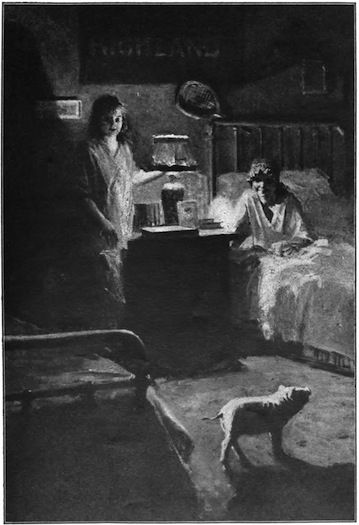

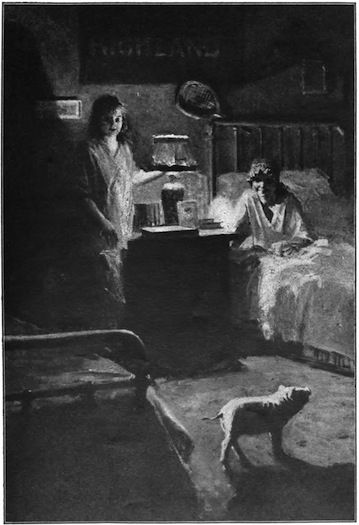

It was somewhere about midnight when Isabelle became aware of the pig. Mabel had been aware of him for a great many sleepless hours. Either he had had too much to eat or not enough. Perhaps he was only lonesome. At any rate he was quiet only when Mabel held him close to her own warm body and kept one or more of her fingers in his mouth. She had spent part of the night on the floor among the shoes; but the floor was hard and Mabel was sleepy; so finally she had crept into her own bed and taken the infant pig with her.

But nothing she could do seemed to please him. His squeals became louder and louder and more and more frequent. At last one of his very best squeals escaped from under the bedclothes.

“My goodness!” gasped Isabelle, suddenly sitting up in bed. “What’s that! Was that you, Mabel?”

“No,” returned Mabel, truthfully. “I didn’t speak.”

“It wasn’t a ‘speak’—it was more like a squeak.”

Piggy chose that moment to let out a smothered “Wee Wee!” in spite of Mabel’s restraining hand.

“Mabel, it is you. Are you sick?”

“I—I’m not sleeping very well,” offered Mabel, trying not to giggle. “I’m quite restless.”

“I thought I heard you eating things in the closet while I was writing. Perhaps you’ve made yourself sick.”

By this time Mabel was about helpless with laughter—it was so amusing to be taken for a pig. But just then her charge took a mean advantage of her. He squirmed suddenly, rolled out of bed and landed with a thump and an astonished grunt on the floor.

“My Uncle!” gasped Isabelle, leaping out of bed and switching on the light. “Are you killed!”

“For goodness’ sake keep still,” growled Mabel. “It isn’t me—it’s my pig!”

“For goodness’ sake keep still,” growled Mabel

The pink pig scuttling here and there across the floor was too much for Isabelle. She plunged into bed again and sat there with horrified eyes on the pig. Suddenly, as he dashed in her direction, she squealed and the pig squealed and they both squealed—a regular duet.

Miss Woodruff in her red flannel nightdress was the first to arrive at the party.

“What!” she demanded, pausing in the doorway, “does this mean?”

Piggy chose this moment for a mad dash for freedom. In his flight through the doorway he brushed the lady’s bare ankles. Miss Woodruff’s wild shrieks were added to Isabelle’s.

Of course everybody in the West Corridor was awake by that time. Brave Victoria Webster, now that Gladys was gone, was again rooming with Augusta and Lillian Thwaite. Pausing for nothing, Victoria rushed through the dark halls toward the portion of the house occupied by Doctor Rhodes. Her lusty cries of “Fire! Fire!” brought all the Rhodes family in bathrobes of assorted colors, to the West Corridor.

By the time they arrived, Lillian and Augusta had added their shrieks to Isabelle’s.

“Stop this noise,” commanded Doctor Rhodes, shaking Augusta. “What are you screaming for?”

“I don’t know,” chattered Augusta.

“What are you screaming for, Lillian?”

“Ow! Ow! I—I don’t know.”

“Miss Woodruff—”

“Why!” gasped Miss Woodruff, suddenly remembering her scarlet attire and bolting for her own room, “I don’t know.”

“Well, Isabelle, what are you screaming for? You seem to be the last.”

“I—I saw a pig!” shuddered Isabelle.

“Nonsense!” returned Doctor Rhodes. “You couldn’t have seen a pig. You’ve been having a nightmare—you ate too much roast pork for dinner.”

“No, no,” insisted Isabelle, “it was a pig.”

“There’s no such animal as a night pig,” returned Doctor Rhodes, with dignity. “Now get back to your beds, all of you, and don’t let me hear another sound from any of you tonight, about pigs or anything else.”

Mabel, tired as she was, stayed awake for an hour wondering what had become of the poor little pig. Although she listened with all her ears, not even the faintest squeal could she hear. Finally she dropped asleep.

“Mabel,” said puzzled Isabelle, the next morning, “I really thought I saw a pig last night. Did you see one?”

“I thought I heard one,” returned Mabel, who was busy in the closet, stuffing a milky bottle into her pocket. “But of course no pig could climb all those stairs.”

“That’s so, too,” said Isabelle. “It may have been that pork—I forgot to eat my apple sauce.”

“I’m sure it was pork,” agreed Mabel, wickedly and truthfully.

At breakfast time Mabel found a note under her plate.

“Dear Mabel: Found at 7 A. M. one pig rooting under the dining

room table for crumbs. Charles is building a pen for him in the

back yard and all is well—thought you’d like to know.

Sallie.”

At recess time, Mabel led Isabelle to the new pig pen. Maude and little Jane Pool were looking over the edge.

“Jane and I thought somebody ought to give him a name so we did,” said Maude, with a wicked glance at Isabelle. “Don’t you think ‘Clarence’ would be a sweet name—for a pig?”

Then, with a gleeful shout, the naughty pair sped away to eat pie under the porch. And Sallie appeared with a message for Mabel.

“Doctor Rhodes wishes to see Miss Bennett in his office,” announced Sallie.

“I’m told,” said Doctor Rhodes, when Mabel stood demurely before him, “that Highland Hall has mysteriously acquired a pig. It occurs to me that you may be able to shed some light on the subject.”

“Yes,” said Mabel, “you’ve guessed right. I brought that pig home. Somebody had to—he was so lonesome.”

“But didn’t I tell you—”

“You didn’t say pigs. You said any of Charles’s family.”

“Hum—so I did. And you kept that animal in your room?”

“I tried to.”

“Then Isabelle really saw a pig?”

“She wasn’t sure at breakfast time,” giggled Mabel.

“You haven’t any more pets concealed on the premises, I suppose! An extra pig or two or a young hippopotamus or anything like that?”

“No,” giggled Mabel, “and I don’t want any more for a long time. A pig is a fearful responsibility.”

“You’ve been punished enough, I see. Well, don’t let it happen again.”

“I won’t,” promised Mabel, cheered by a certain twitching line in Doctor Rhodes’s cheek. “I’ve had enough pets to last a long time—besides one roommate is just about all Isabelle can stand.”