CHAPTER III.

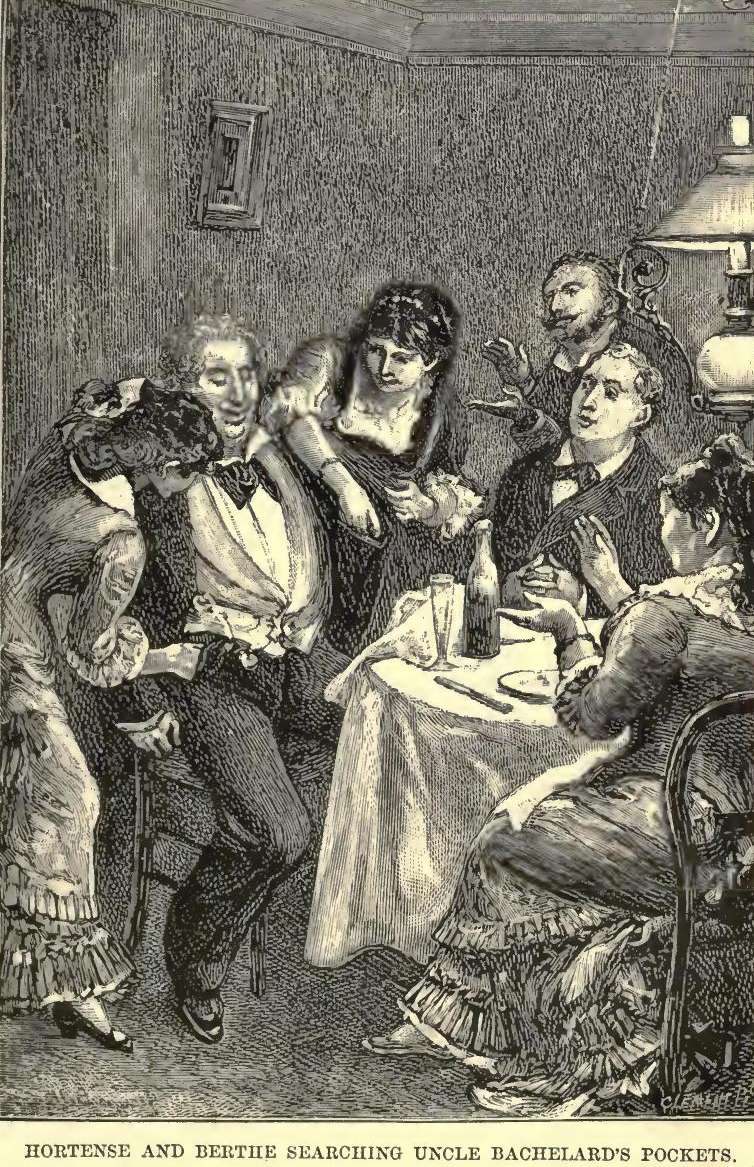

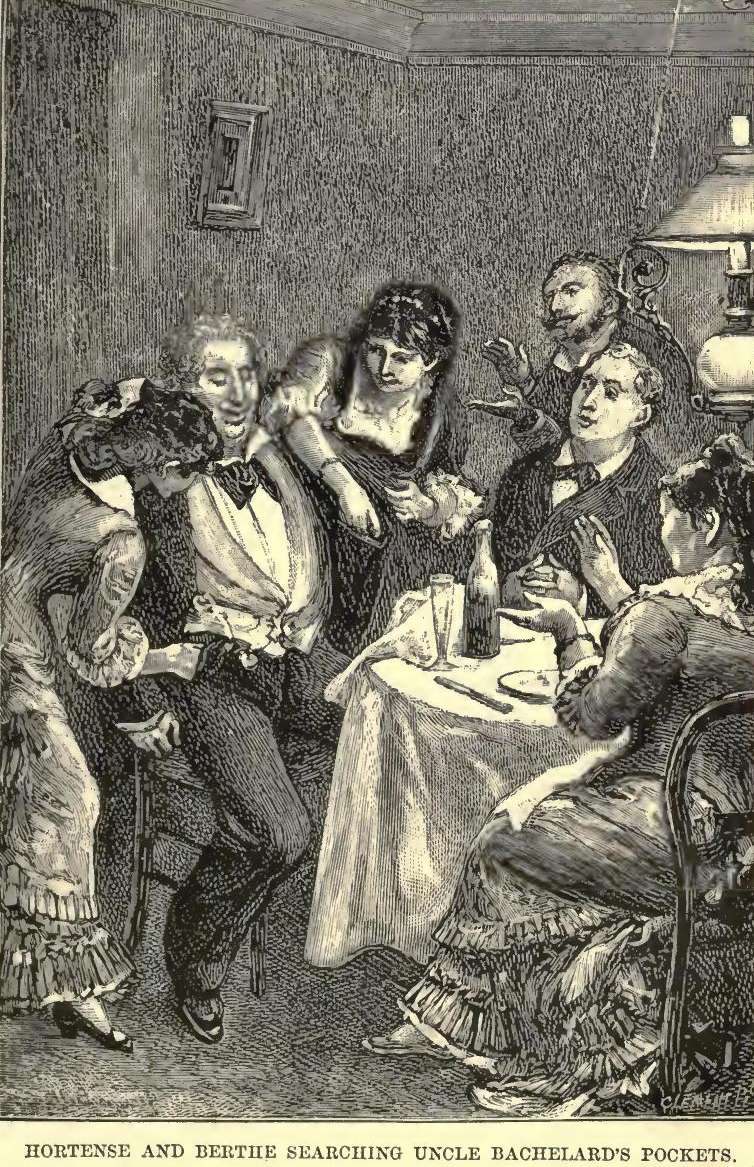

So soon as the fish was served, skate of doubtful freshness with black butter, which that bungler Adèle had drowned in a flood of vinegar, Hortense and Berthe, seated on the right and left of uncle Bachelard, incited him to drink, filling his glass one after the other, and repeating:

“It’s your saint’s-day, drink now, drink! Here’s your health, uncle!”

They had plotted together to make him give them twenty francs. Every year, their provident mother placed them thus on either side of her brother, abandoning him to them. But it was a difficult task, and required all the greediness of two girls prompted by dreams of Louis XV. shoes and five button gloves. To get him to give the twenty francs, it was necessary to make the uncle completely drunk. He was ferociously miserly whenever he found himself amongst his relations, though out of doors he squandered in crapulous boozes the eighty thousand francs he made each year out of his commission business. Fortunately, that evening, he was already half fuddled when he arrived, having passed the afternoon with the wife of a dyer of the Faubourg Montmartre, who kept a stock of Marseilles vermouth expressly for him.

“Your health, my little ducks!” replied he each time, with his thick husky voice, as he emptied his glass.

Covered with jewellery, a rose in his button-hole, enormous in build, he filled the middle of the table, with his broad shoulders of a boozing and brawling tradesman, who has wallowed in every vice. His false teeth lit up with too harsh a whiteness his ravaged face, the big red nose of which blazed beneath the snowy crest of his short cropped hair; and, now and again, his eyelids dropped of themselves over his pale and misty eyes. Gueulin, the son of one of his wife’s sisters, affirmed that his uncle had not been sober during the ten years he had been a widower.

“Narcisse, a little skate, I can recommend it,” said Madame Josserand, smiling at her brother’s tipsy condition, though at heart it made her feel rather disgusted.

She was sitting opposite to him, having little Gueulin on her left, and another young man on her right, Hector Trublot, to whom she was desirous of showing some politeness. She usually took advantage of family gatherings like the present to get rid of certain invitations she had to return; and it was thus that a lady living in the house, Madame Juzeur, was also present, seated next to Monsieur Josserand. As the uncle behaved very badly at table, and it was the expectation of his fortune alone which enabled them to put up with him without absolute disgust, she only had intimate acquaintances to meet him or else persons whom she thought it was no longer worth while trying to dazzle. For instance, she had at one time thought of finding a son-in-law in young Trublot, who was employed at a stockbroker’s, whilst waiting till his father, a wealthy man, purchased him a share in the business; but, Trublot having professed a determined objection to matrimony, she no longer stood upon ceremony with him, even placing him next to Saturnin, who had never known how to eat decently. Berthe, who always had a seat beside her brother, was commissioned to subdue him with a look, whenever he put his fingers too much into the gravy.

After the fish came a meat pie, and the young ladies thought the moment arrived to commence their attack.

“Take another glass, uncle!” said Hortense. “It is your saint’s day. Don’t you give anything when it’s your saint’s-day?”

“Dear me! why of course,” added Berthe naively. “People always give something on their saint’s-day. You must give us twenty francs.”

On hearing them speak of money, Bachelard at once exaggerated his tipsy condition. It was his usual dodge; his eyelids dropped, and he became quite idiotic.

“Eh? what?” stuttered he.

“Twenty francs. You know very well what twenty francs are, it is no use your pretending you don’t,” resumed Berthe. “Give us twenty francs, and we will love you, oh! we will love you so much!”

They threw their arms round his neck, called him the most endearing names, and kissed his inflamed face without the least repugnance for the horrid odour of debauchery which he exhaled. Monsieur Josserand, whom these continual fumes of absinthe, tobacco and musk upset, had a feeling of disgust on seeing his daughters’ virgin charms rubbing up against those infamies gathered in the vilest places.

“Leave him alone!” cried he.

“Why?” asked Madame Josserand, giving her husband a terrible look. “They are amusing themselves. If Narcisse wishes to give them twenty francs, he is quite at liberty to do so.”

“Monsieur Bachelard is so good to them!” complacently murmured little Madame Juzeur.

But the uncle struggled, becoming more idiotic than ever, and repeating, with his mouth full of saliva:

“It’s funny. I don’t know, word of honour! I don’t know.”

Then, Hortense and Berthe, exchanging a glance, released him. No doubt he had not had enough to drink. And they again resorted to filling his glass, laughing like courtesans who intend robbing a man. Their bare arms, of an adorable youthful plumpness, kept passing every minute under the uncle’s big flaming nose.

Meanwhile, Trublot, like a quiet fellow who takes his pleasures alone, was watching Adèle as she turned heavily round the table. Being very short-sighted he thought her pretty, with her pronounced Breton features and her hair the colour of dirty hemp. When she brought in the roast, a piece of veal, she leant right over his shoulder, to reach the centre of the table; and he, pretending to pick up his napkin, gave her a good pinch on the calf of her leg. The servant, not understanding, looked at him, as though he had asked her for some bread.

“What is it?” said Madame Josserand. “Did she knock against you, sir? Oh! that girl! she is so awkward! But, you know, she is quite new to the work; she will be better when she has had a little training.”

“No doubt, there is no harm done,” replied Trublot, stroking his bushy black beard with the serenity of a young Indian god.

The conversation was becoming more animated in the diningroom, at first icy cold, and now gradually warming with the fumes of the dishes. Madame Juzeur was once more confiding to Monsieur Josserand the dreariness of her thirty years of solitary existence. She raised her eyes to heaven, and contented herself with this discreet allusion to the drama of her life: her husband had left her after ten days of married bliss, and no one knew why; she said nothing more. Now, she lived by herself in a lodging that was as soft as down and always closed, and which was frequented by priests.

“It is so sad, at my age!” murmured she languishingly, cutting up her veal with delicate gestures.

“A very unfortunate little woman,” whispered Madame Josserand in Trublot’s ear, with an air of profound sympathy.

But Trublot glanced indifferently at this clear-eyed devotee, so full of reserve and hidden meanings. She was not his style.

Then there was a regular panic. Saturnin, whom Berthe was not watching so closely, being too busy with her uncle, had amused himself by cutting up his meat into various designs on his plate. This poor creature exasperated his mother, who was both afraid and ashamed of him; she did not know how to get rid of him, not daring through pride to make a workman of him, after having sacrificed him to his sisters by having removed him from the school where his slumbering intelligence was too long awakening; and, during the years he had been hanging about the house, useless and stinted, she was in a constant state of fright whenever she had to let him appear before company. Her pride suffered cruelly.

“Saturnin!” cried she.

But Saturnin began to chuckle, delighted with the mess he had made in his plate. He did not respect his mother, but called her roundly a great liar and a horrid nuisance, with the perspicacity of madmen who think out loud. Things certainly seemed to be going wrong. He would have thrown his plate at her head, if Berthe, reminded of her duties, had not looked him straight in the face. He tried to resist; then the fire in his eyes died out; he remained gloomy and depressed on his chair, as though in a dream, until the end of the meal.

“I hope, Gueulin, that you have brought your flute?” asked Madame Josserand, trying to dispel her guests’ uneasiness.

Gueulin was an amateur flute-player, but solely in the houses where he was treated without ceremony.

“My flute! Of course I have,” replied he.

He was absent-minded, his carroty hair and whiskers were more bristly than usual, as he watched with deep interest the young ladies’ manoeuvres around their uncle. Employed at an assurance office, he would go straight to Bachelard on leaving off work, and stick to him, visiting the same cafés and the same disreputable places. Behind the big, ill-shaped body of the one, the little pale face of the other was sure always to be seen.

“Cheerily, there! stick to him!” said he, suddenly, like a true sportsman.

The uncle was indeed losing ground. When, after the vegetables, French beans swimming in water, Adèle placed a vanilla and currant ice on the table, it caused unexpected delight amongst the guests; and the young ladies took advantage of the situation to make the uncle drink half of the bottle of champagne, which Madame Josserand had bought for three francs of a neighbouring grocer. He was becoming quite affectionate, and forgetting his pretended idiocy.

“Eh, twenty francs! Why twenty francs? Ah! you want twenty francs! But I have not got them, really now. Ask Gueulin. Is it not true, Gueulin, that I forgot my purse, and that you had to pay at the café? If I had them, my little ducks, I would give them to you, you are so nice.”

Gueulin was laughing in his cool way, making a noise like a pulley that required greasing. And he murmured:

“The old swindler!”

Then, suddenly, unable to restrain himself, he cried:

“Search him!”

So Hortense and Berthe again threw themselves on the uncle, this time without the least restraint. The desire for the twenty francs, which their good education had hitherto kept within bounds, bereft them of their senses in the end, and they forgot everything else. The one, with both hands, examined his waistcoat pockets, whilst the other buried her fingers inside the pockets of his frock-coat. The uncle, however, pressed back on his chair, still struggled; but he gradually burst out into a laugh—a laugh broken by drunken hiccoughs.

“On my word of honour, I haven’t a sou! Leave off, do; you’re tickling me.”

“In the trousers!” energetically exclaimed Gueulin, excited by the spectacle.

And Berthe resolutely searched one of the trouser pockets.

Their hands trembled; they were both becoming exceedingly rough, and could have smacked the uncle. But Berthe uttered a cry of victory: from the depths of the pocket she brought forth a handful of money, which she spread out in a plate; and there, amongst a heap of coppers and pieces of silver, was a twenty-franc piece.

“I have it!” said she, her face all red, her hair undone, as she tossed the coin in the air and caught it again.

There was a general clapping of hands, every one thought it very funny. It created quite a hubbub, and was the success of the dinner. Madame Josserand looked at her daughters with a mother’s tender smile. The uncle, who was gathering up his money, sententiously observed that, when one wanted twenty francs, one should earn them. And the young ladies, worn out and satisfied, were panting on his right and left, their lips still trembling in the enervation of their desire.

A bell was heard to ring. They had been eating slowly, and the other guests were already arriving. Monsieur Josserand, who had decided to laugh like his wife, enjoyed singing some of Béranger’s songs at table; but as this outraged his better half’s poetic tastes, she compelled him to keep quiet. She got the dessert over as quickly as possible, more especially as, since the forced present of the twenty francs, the uncle had been trying to pick a quarrel, complaining that his nephew, Léon, had not deigned to put himself out to come and wish him many happy returns of the day. Léon was only coming to the evening party. At length, as they were rising from table, Adèle said that the architect from the floor below and a young man were in the drawing-room.

“Ah! yes, that young man,” murmured Madame Juzeur, accepting Monsieur Josserand’s arm. “So you have invited him? I saw him to-day talking to the doorkeeper. He is very good-looking.”

Madame Josserand was taking Trublot’s arm, when Saturnin, who had been left by himself at the tableland who had not been roused from slumbering with his eyes open by all the uproar about the twenty francs, kicked back his chair, in a sudden outburst of fury, shouting:

“I won’t have it, damnation! I won’t have it!”

It was the very thing his mother always dreaded. She signalled to Monsieur Josserand to take Madame Juzeur away. Then she freed herself from Trublot, who understood, and disappeared; but he probably made a mistake, for he went off in the direction of the kitchen, close upon Adèle’s heels. Bachelard and Gueulin, without troubling themselves about the maniac, as they called him, chuckled in a corner, whilst playfully slapping one another.

“He was so peculiar, I felt there would be something this evening,” murmured Madame Josserand, uneasily. “Berthe, come quick!”

But Berthe was showing the twenty-franc piece to Hortense. Saturnin had caught up a knife. He repeated:

“Damnation! I won’t have it! I’ll rip their stomachs open!”

“Berthe!” called her mother in despair.

And, when the young girl hastened to the spot, she only just had time to seize him by the hand and prevent him from entering the drawing-room. She shook him angrily, whilst he tried to explain, with his madman’s logic.

“Let me be, I must settle them. I tell you it’s best. I’ve had enough of their dirty ways. They’ll sell the whole lot of us.”

“Oh! this is too much!” eried Berthe. “What is the matter with you? what are you talking about?”

He looked at her in a bewildered way, trembling with a gloomy rage, and stuttered:

“They’re going to marry you again. Never, you hear! I won’t have you hurt.”

The young girl eould not help laughing. Where had he got the idea from that they were going to marry her? But he nodded his head: he knew it, he felt it. And as his mother intervened to try and calm him, he grasped his knife so tightly that she drew back. However, she trembled for fear he should be overheard, and hastily told Berthe to take him away and lock him in his room; whilst he, becoming crazier than ever, raised his voice:

“I won’t have you married, I won’t have you hurt. If they marry you, I’ll rip their stomachs open.”

Then Berthe put her hands on his shoulders, and looked him straight in the face.

“Listen,” said she, “keep quiet, or I will not love you any more.”

He staggered, despair softened the expression of his face, his eyes filled with tears.

“You won’t love me any more, you won’t love me any more. Don’t say that. Oh! I implore you, say that you will love me still, say that you will love me always, and that you will never love any one else.”

She had seized him by the wrist, and she led him away as gentle as a child.

In the drawing-room Madame Josserand, exaggerating her intimacy, called Campardon her dear neighbour. Why had Madame Campardon not done her the great pleasure of coming also? and on the architect replying that his wife still continued poorly, she exelaimed that they would have been delighted to have received her in her dressing-gown and her slippers. But her smile never left Octave, who was conversing with Monsieur Josserand; all her amiability was directed towards him, over Campardon’s shoulder. When her husband introduced the young man to her, her cordiality was so great that the latter felt quite uncomfortable.

Other guests were arriving; stout mothers with skinny daughters, fathers and uncles scarcely roused from their office drowsiness, pushing before them flocks of marriageable young ladies. Two lamps, with pink paper shades, lit up the drawingroom with a pale light, which only faintly displayed the old, worn, yellow velvet covered furniture, the scratched piano, and the three smoky Swiss views, which looked like black stains on the cold, bare, white and gold panels. And, in this miserly light, the guests—poor, and, so to say, worn-out figures, without resignation, and whose attire was the cause of much pinching and saving—seemed to become obliterated. Madame Josserand wore her fiery costume of the day before; only, with a view of throwing dust in people’s eyes, she had passed the day in sewing sleeves on to the body, and in making herself a lace tippet to cover her shoulders; whilst her two daughters, seated beside her in their dirty cotton jackets, vigorously plied their needles, rearranging with new trimmings their only presentable dresses, which they had been thus altering bit by bit ever since the previous winter.

After each ring at the bell, the sound of whispering issued from the ante-chamber. They conversed in low tones in the gloomy drawing-room, where the forced laugh of some young lady jarred at times like a false note. Behind little Madame Juzeur, Bachelard and Gueulin were nudging each other, and making smutty remarks; and Madame Josserand watched them with an alarmed look, for she dreaded her brother’s vulgar behaviour. But Madame Juzeur might hear anything; her lips quivered, and she smiled with angelic sweetness as she listened to the naughty stories. Uncle Bachelard had the reputation of being a dangerous man. His nephew, on the contrary, was chaste. No matter how splendid the opportunities were, Gueulin declined to have anything to do with women upon principle, not that he disdained them, but because he dreaded the morrows of bliss: always very unpleasant, he said.

Berthe at length appeared, and went hurriedly up to her mother.

“Ah, well! I have had a deal of trouble!” whispered she in her ear. “He would not go to bed, so I double-locked the door. But I am afraid he will break everything in the room.”

Madame Josserand violently tugged at her dress. Octave, who was close to them, had turned his head.

“My daughter, Berthe, Monsieur Mouret,” said she, in her most gracious manner, as she introduced them. “Monsieur Octave Mouret, my darling.”

And she looked at her daughter. The latter was well acquainted with this look, which was like an order to clear for action, and which recalled to her the lessons of the night before. She at once obeyed, with the complaisance and the indifference of a girl who no longer stops to examine the person she is to marry. She prettily recited her little part with the easy grace of a Parisian already weary of the world, and acquainted with every subject, and she talked enthusiastically of the South, where she had never been. Octave, used to the stiffness of provincial virgins, was delighted with this little woman’s cackle and her sociable manner.

Presently, Trublot, who had not been seen since dinner was over, entered stealthily from the dining-room; and Berthe, catching sight of him, asked thoughtlessly where he had been. He remained silent, at which she felt very confused; then, to put an end to the awkward pause which ensued, she introduced the two young men to each other. Her mother had not taken her eyes off her; she had assumed the attitude of a commander-in-chief, and directed the campaign from the easy-chair in which she had settled herself. When she judged that the first engagement had given all the result that could have been expected from it, she recalled her daughter with a sign, and said to her, in a low voice:

“Wait till the Vabre’s are here before commencing your music. And play loud.”

Octave, left alone with Trublot, began to engage him in conversation.

“A charming person.”

“Yes, not bad.”

“The young lady in blue is her elder sister, is she not? She is not so good-looking.”

“Of course not; she is thinner!”

Trublot, who looked without seeing with his near-sighted eyes, had the broad shoulders of a solid male, obstinate in his tastes. He had come back from the kitchen perfectly satisfied, crunching little black things which Octave recognised with surprise to be coffee berries.

“I say,” asked he abruptly, “the women are plump in the South, are they not?”

Octave smiled, and at once became on an excellent footing with Trublot. They had many ideas in common which brought them closer together. They exchanged confidences on an out-of-the-way sofa; the one talked of his employer at “The Ladies’ Paradise,” Madame Hédouin, a confoundedly fine woman, but too cold; the other said that he had been put on to the correspondence, from nine to five, at his stockbroker’s, Monsieur Desmarquay, where there was a stunning maid servant. Just then the drawing-room door opened, and three persons entered.

“They are the Vabres,” murmured Trublot, bending over towards his new friend. “Auguste, the tall one, he who has a face like a sick sheep, is the landlord’s eldest son—thirty-three years old, ever suffering from headaches which make his eyes start from his head, and which, some years ago, prevented him from continuing to learn Latin; a sullen fellow who has gone in for trade. The other, Théophile, that abortion with carroty hair and thin beard, that little old-looking man of twenty-eight, ever shaking with fits of coughing and of rage, tried a dozen different trades, and then married the young woman who leads the way, Madame Valérie—”

“I have already seen her,” interrupted Octave. “She is the daughter of a haberdasher of the neighbourhood, is she not? But how those veils deceive one! I thought her pretty. She is only peculiar, with her shrivelled face and her leaden complexion.”

“She is another who is not my ideal,” sententiously resumed Trublot. “She has superb eyes, and that is enough for some men. But she’s a thin piece of goods.”

Madame Josserand had risen to shake Valérie’s hand.

“How is it,” cried she, “that Monsieur Vabre is not with you? and that neither Monsieur nor Madame Duveyrier have done us the honour of coming? They promised us though. Ah! it is very wrong of them!”

The young woman made excuses for her father-in-law, whose age kept him at home, and who, moreover, preferred to work of an evening. As for her brother and sister-in-law, they had asked her to apologise for them, they having received an invitation to an official party, which they were obliged to attend. Madame Josserand bit her lips. She never missed one of the Saturdays at home of those stuck-up people on the first floor, who would have thought themselves dishonoured had they ascended, one Tuesday, to the fourth. No doubt her modest tea was not equal to their grand orchestral concerts. But, patience! when her two daughters were married, and she had two sons-in-law and their relations to fill her drawing-room, she also would go in for choruses.

“Get yourself ready,” whispered she in Berthe’s ear.

They were about thirty, and rather tightly packed, for the parlour, having been turned into a bedroom for the young ladies, was not thrown open. The new arrivals distributed handshakes round. Valérie seated herself beside Madame Juzeur, whilst Bachelard and Gueulin made unpleasant remarks out loud about Théophile Vabre, whom they thought it funny to call “good for nothing.” Monsieur Josserand—who in his own home kept himself so much in the background that one would have taken him for a guest, and whom one would fail to find when wanted, even though he were standing close by—was in a corner listening in a bewildered way to a story related by one of his old friends, Bonnaud. He knew Bonnaud, who was formerly the general accountant of the Northern railway, and whose daughter had married in the previous spring? Well! Bonnaud had just discovered that his son-in-law, a very respectable-looking man, was an ex-clown, who had lived for ten years at the expense of a female circus-rider.

“Silence! silence!” murmured some good-natured voices. Berthe had opened the piano.

“Really!” explained Madame Josserand, “it is merely an unpretentious piece, a simple reverie. Monsieur Mouret, you like music, I think. Come nearer then. My daughter plays pretty fairly—oh! purely as an amateur, but with expression; yes, with a great deal of expression.”

“Caught!” said Trublot in a low voice. “The sonata stroke.” Octave was obliged to leave his seat and stand up beside the piano. To see the caressing attentions which Madame Josserand showered upon him, it seemed as though she were making Berthe play solely for him.

“‘The Banks of the Oise,’” resumed she. “It is really very pretty. Come begin, my love, and do not be confused. Monsieur Mouret will be indulgent.”

The young girl commenced the piece without being in the least confused. Besides, her mother kept her eyes upon her like a sergeant ready to punish with a blow the least theoretical mistake. Her great regret was that the instrument, worn-out by fifteen years of daily scales, did not possess the sonorous tones of the Duveyriers’ grand piano; and her daughter never played loud enough in her opinion.

After the sixth bar, Octave, looking thoughtful and nodding his head at each spirited passage, no longer listened. He looked at the audience, the politely absent-minded attention of the men, and the affected delight of the women, all that relaxation of persons for a moment at rest, but soon again to be harassed by the cares of every hour, the shadows of which, before long, would be once more reflected on their weary faces. Mothers were visibly dreaming that they were marrying their daughters, whilst a smile hovered about their mouths, revealing their fierce-looking teeth in their unconscious abandonment; it was the mania of this drawing-room, a furious appetite for sons-in-law, which consumed these worthy middle-class mothers to the asthmatic sounds of the piano.

The daughters, who were very weary, were falling asleep, with their heads dropping on to their shoulders, forgetting to sit up erect. Octave, who had a certain contempt for young ladies, was more interested in Valerie—she looked decidedly ugly in her peculiar yellow silk dress, trimmed with black satin—and feeling ill at ease, yet attracted all the same, his gaze kept returning to her; whilst she, with a vague look in her eyes, and unnerved by the discordant music, was smiling like a crazy person.

At this moment quite a catastrophe occurred. A ring at the bell was heard, and a gentleman entered the room without the least regard for what was taking place.

“Oh! doctor!” said Madame Josserand angrily.

Doctor Juillerat made a gesture of apology, and stood stockstill. Berthe, at this moment, was executing a little passage with a slow and dreamy fingering, which the guests greeted with flattering murmurs. Ah! delightful! delicious! Madame Juzeur was almost swooning away, as though being tickled. Hortense, who was standing beside her sister, turning the pages, was sulkily listening for a ring at the bell amidst the avalanche of notes; and, when the doctor entered, she made such a gesture of disappointment that she tore one of the pages on the stand. But, suddenly, the piano trembled beneath Berthe’s weal: fingers, thrumming away like hammers; it was the end of the reverie, amidst a deafening uproar of clangorous chords.

There was a moment of hesitation. The audience was waking up again.. Was it finished? Then the compliments burst out on all sides. Adorable! a superior talent!

“Mademoiselle is really a first-rate musician,” said Octave, interrupted in his observations. “No one has ever given me such pleasure.”

“Do you really mean it, sir?” exclaimed Madame Josserand delighted. “She does not play badly, I must admit. Well! we have never refused the child anything; she is our treasure! She possesses every talent she wished for. Ah! sir, if you only knew her.”

A confused murmur of voices again filled the drawing-room. Berthe very calmly received the praise showered upon her, and did not leave the piano, but sat waiting till her mother relieved her from fatigue-duty. The latter was already speaking to Octave of the surprising manner in which her daughter dashed off “The Harvesters,” a brilliant gallop, when some dull and distant thuds created a stir amongst the guests. For several moments past there had been violent shocks, as though some one was trying to burst a door open. Everybody left off talking, and looked about inquiringly.

“What is it?” Valérie ventured to ask. “I heard it before, during the finish of the piece.”

Madame Josserand had turned quite pale. She had recognised Saturnin’s blows. Ah! the wretched lunatic! and in her mind’s eye she beheld him tumbling in amongst the guests. If he continued hammering like that, it would be another marriage done for!

“It is the kitchen door slamming,” said she with a constrained smile. “Adèle never will shut it. Go and sec, Berthe.”

The young girl had also understood. She rose and disappeared. The noise ceased at once, but she did not return immediately. Uncle Bachelard, who had scandalously disturbed “The Banks of the Oise” with reflections uttered out loud, finished putting his sister out of countenance by calling to Gueulin that he felt awfully bored and was going to have a grog. They both returned to the dining-room, banging the door behind them.

“That dear old Narcisse, he is always original!” said Madame Josserand to Madame Juzeur and Valérie, between whom she had gone and seated herself. “His business occupies him so much! You know, he has made almost a hundred thousand francs this year!”

Octave, at length free, had hastened to rejoin Trublot, who was half asleep on the sofa. Near them, a group surrounded Doctor Juillerat, the old medical man of the neighbourhood, not over brilliant, but who had become in course of time a good practitioner, and who had delivered all the mothers in their confinements